Hurricane Katrina paper

advertisement

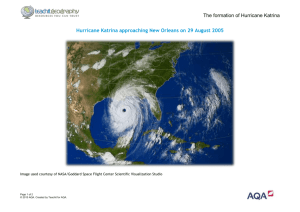

Running head: HURRICANE KATRINA 1 Hurricane Katrina: Disaster management and public health Dr. Hollie Pavlica Health Policy and Management MPH 525 Katelyn Strasser February 2014 2 HURRICANE KATRINA Table of Contents Chapter Page 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………….3 2. Effects of the Hurricane………………………………………………………………..3 3. Warnings……………………………………………………………………………….4 4. Public Health Preparedness…………………………………………………………….5 5. Government Response…………………………………………………………………5 Local and State Governments……………………………………………………..5 Federal Government………………………………………………………………6 6. Reasons for Delay……………………………………………………………………..7 7. Lessons Learned……………………………………………………………………….9 8. Triumphs……………………………………………………………………………...10 9. Summary……………………………………………………………………………...11 10. Recommendations…………………………………………………………………...12 References………………………………………………………………………………..13 3 HURRICANE KATRINA Hurricane Katrina: Disaster management and public health Chapter 1 Introduction Hurricane Katrina of August 2005 is one of the most devastating disasters to occur in recent years, as well as in the history of the United States. Events like natural disasters, release of chemical agents, disease epidemics, or man-made environmental disasters all call for public health preparedness. Public health preparedness deals with preparing for and gathering resources in the event that one of these types of disasters would occur. Disaster management involves government at the local, state, and federal levels. This paper will outline the events surrounding hurricane Katrina and the response from all levels of government. It will also analyze lessons learned from the disaster and triumphs in the midst of this crisis. The paper will end with recommendations about how local and state governments can play a larger role in emergency preparedness (Teitelbaum & Wilensky, 2013) Chapter 2 Effects of the Hurricane Hurricane Katrina’s disastrous hurricane conditions and subsequent flooding caused a record setting amount of destruction in parts of Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, with New Orleans being the most populous city affected (Kelman, 2007). The hurricane resulted in huge economic and financial loss. Of even greater importance was the damage of property, displacement of people, and untimely deaths of many. In fact, Hurricane Katrina was one of the five deadliest hurricanes to ever hit the United States (Fritz et al., 2008). Approximately 1,330 people died in this event, with about 80 percent 4 HURRICANE KATRINA of these fatalities coming from the New Orleans Metropolitan area (The White House, n.d.). Chapter 3 Warnings Although Hurricane Katrina shocked many people, numerous warnings and concerns by experts had been given far in advance of the storm. New Orleans’ nickname “City in the Bowl” describes how the city is situated below the level of surrounding sea, river, and lake water (Kelman, 2007). This left the city especially vulnerable to flooding (Parker, Stern, Paglia & Brown, 2009). Experts also agree that infrastructure problems and the building of many low-lying homes added to flooding possibilities. The Corps of Engineers tried to warn city officials that soil erosion and subsidence had caused parts of the levee system to sink at least three feet (Shughart, 2011). The structures that were supposed to protect the city for two to three hundred years could not withstand the effects of upper-category hurricanes (Parker et al., 2009). Multiple people commented on the impending danger. For example, PBS and American Radio Works both made documentaries based on the risk of a hurricane hitting New Orleans. Joe Allbaugh, who was the first FEMA director of the Bush administration, said in 2002 that, “there are a half-dozen or so contingencies around the nation that cause me great concern, and one of them is [in New Orleans]” (Parker et al., 2009). In 2001, FEMA listed the event of an upper-category hurricane as “one of the three most likely catastrophes facing the nation. FEMA even initiated a hands-on preparedness event when it carried out the fictional Hurricane Pam exercise with local and state emergency managers. Although this exercise prepared its participants for a 5 HURRICANE KATRINA larger death toll than Katrina, its scenario did not include the breaching of levees around New Orleans (Parker et al., 2009) Chapter 4 Public Health Preparedness Public health preparedness involves the work of every level of government. The local and state governments are responsible for creating policies, building infrastructure, and working with its citizens to disseminate health security information. States have police powers, which means that they have the power to regulate health and safety. States also have to create their own emergency preparedness plans and carry out emergency preparedness training. Preparedness training can be unique for all states, depending on the unique needs for that state, but they must meet some national preparedness goals. The federal government works in collaboration with local and state governments, but also is responsible for domestic health preparedness. It is crucial that the federal government works with other countries “to ensure an effective worldwide system for preparedness, information sharing, and collaboration in preventing, detecting, reporting, and responding to public health threats.” Also, multiple federal agencies such as Health and Human Services, Department of Homeland Security, and the Environmental Protection Agency offer services (Teitelbaum & Wilensky, 2013). Chapter 5 Government Response Local and State Governments Many have argued that the response to Hurricane Katrina was not as speedy as it should have been, and that there were breakdowns of the emergency response system at HURRICANE KATRINA 6 every level. All of the area’s public officials were warned of the impending storm, but many were accused of being slow to act. On August 26, Louisiana’s governor issued a state of emergency, which triggered her state’s disaster plan. She then left the decisions about mandatory evacuation to be made by Mayor Ray Nagin. Nagin also received a telephone call from the director of the National Hurricane Center to inform him of the significance of this storm. Still, Nagin did not order a mandatory evacuation until the storm was within 24 hours of hitting the coast. Many people were not able to evacuate in this short of time span. Then the governor and his officials decided to seek shelter at a Hyatt Regency hotel rather than at the city’s Mobile Command Center or Louisiana’s emergency operations facility in Baton Rouge, where other state and local officials waited out the storm. This caused the Mayor to be cut off from the rest of the officials for two days, leaving him and others stranded with no form of communication. Disrupted communication has also been blamed for Governor Blanco’s inability to give a list of requests to the White House until September 1, four days after the hurricane first hit (Shughart, 2011). Federal Government Although people were upset with the response of the local and state governments, most of the blame was placed on the federal government, especially the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). FEMA works with state and local governments to plan for disasters, and to train local responders how to act in the event of an emergency (Parker et al., 2009). When disasters do strike, FEMA offers its assistance to individuals, families, and businesses. Through this agency, the federal government 7 HURRICANE KATRINA also offers disaster assistance through loans by the Small Business Administration (Plitt & Maldonado, 2012). In the case of Hurricane Katrina, FEMA’s assistance came much later than anticipated. President Bush declared an emergency in Louisiana on Saturday, August 27. This declaration should have been the beginning of FEMA working with state and local officials to plan for the upcoming storm. One FEMA official noted that the agency did not send enough food, water, and medical supplies before the storm hit. Once federal agencies did recognize the importance of a national response, sixteen thousand federal employees were sent to the Gulf Coast (Shughart, 2011)). Another 63,000 military personnel were deployed to the area. This was the largest number of military personnel sent to any disaster in the history of the United States (Miller, 2012). Congress also set aside $88 billion for relief, recovery, and rebuilding in the area. Another $5.8 billion was underwritten in disaster loans by the Small Business Administration (Shughart, 2011). Chapter 6 Reasons for Delay Reasons for the federal government’s slow response to the disaster are multifaceted as well as complicated. After the attacks of September 11, 2001, FEMA was reorganized with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). This led the agency to lose some of its autonomy and authority to mainly immerse its undertakings in emergency preparedness. Instead, the DHS led FEMA to focus more of its mission and budget on planning for future terrorist attacks. This forced many of FEMA’s most experienced members to leave (Shughart, 2011). Relationships with local and state emergency response programs also weakened as the Office of Domestic Preparedness HURRICANE KATRINA 8 took on the control of preparation grants. The partnerships that were so essential to FEMA’s success in times of disaster were now strained (Parker et al., 2009). A lack of experience in this manner caused confusion and delay in the Department of Homeland Security when the hurricane finally did arrive. White House and Defense Department officials also questioned whether to federalize National Guard units in the storm area. Supposedly, President George W. Bush asked Louisiana’s Democratic governor Kathleen Blanco to give control of local law enforcement and military to the federal government. After a day of contemplation, she refused because she thought that this would allow the president to claim credit for relief efforts that were starting to show improvement. Blanco may have been inclined to have this attitude toward the President because of a notion that historically, he had been quicker to offer assistance in electoral battleground states. One example was the speedy aid that arrived to Florida after Hurricane Charley. This was a notably different response than the four days it took to visit after Hurricane Katrina (Shughart, 2011). Although blame could be placed on many different people during the Hurricane Katrina disaster, some common trends seem to plague all disaster relief preparedness programs. Policies and political agendas at both the state and national level are crowded with many pressing issues. The topics that are the most immediate and those with certain consequences tend to receive the most attention. For example, during the time frame of Hurricane Katrina, the government was focused on domestic tax cuts and the War on Terror. Other threats such as counterterrorism, immigration border security, and threats of avian influenza also plagued the DHS at the time. Agendas concerned with emergency preparedness are pushed aside because they are not immediate threats. When these 9 HURRICANE KATRINA possibilities do become realities, appropriate policies are not in place (Parker et al., 2009). Chapter 7 Lessons Learned All levels of government, especially the federal government, learned lessons from this disaster that will hopefully prevent this large-scale crisis from occurring again. One lesson is that the Executive Branch agencies need to be better equipped to manage disasters and communicate with the appropriate groups. The federal government should also work on implementing the National Preparedness Goals (NPGs) (The White House, n.d.) A National Response Plan had been made before Hurricane Katrina, but it gave a sense of false hope because the plan was untested at the time (Parker et al., 2009). Another lesson was that the DHS should review current laws and policies about communication during an emergency. As noted earlier, many key players in the emergency response lost communication, further delaying aid to the area. During the storm, three million people lost telephone services, and many of the 911 emergency call centers were unable to function. Nearly half of all radio and television stations lost access to their audience. The federal government plans on working with the Office of Science and Technology Policy to develop a National Communications Strategy that would support communication during disasters (The White House, n.d). A third lesson learned was that certain aspects of public health and medical aid need to be more readily offered during these critical periods. Unfortunately, Hurricane Katrina hit two states (Louisiana and Mississippi) that had public health infrastructures ranking 49th and 50th in the United States. The flooding caused many people to lose 10 HURRICANE KATRINA access to their homes, and medications and medical devices that people with chronic conditions rely on to survive. Numerous hospitals and clinics were too damaged to operate. People also lacked access to clean water, and sanitation was an issue. To lessen problems like these in the future, the federal government would like to partner the Department of Health and Human Services with the Department of Homeland Security to strengthen the federal government’s competency in delivering public health and medical aid in an emergency (The White House, n.d.). Chapter 8 Triumphs Even with all the flaws in the emergency response system at the time of Hurricane Katrina, there were some noteworthy parts to the process. One aspect that really helped the relief effort was the massive amount of volunteer and non-profit organizations that offered their services during this time. The USA Freedom Corps and Governor’s State Service Commissions both helped bring volunteers from non-profit organizations into the aid process. The Citizen Corps also brought more than 14,000 volunteers into the recovery efforts. Faith-based organizations such as Southern Baptist Relief, Operation Blessing, and the Salvation Army came to provide aid in the form of food, supplies, and shelter. These were just a few of the groups that volunteered their time and resources to help those affected by the hurricane (The White House, n.d.). The federal government also commended the actions taken by various law enforcement groups. Local fire and police departments, along with emergency response units worked long past scheduled hours to assist those in need. Other cities and states also offered their law enforcement members to help in recovery and rescue missions. For 11 HURRICANE KATRINA example, the Fire Department of New York City and the New York City Police Department sent hundreds of its members to the disaster area, along with various fire trucks, police cruisers, schools buses, and transit buses (The White House, n.d.). Another positive result of Hurricane Katrina was the development and implementation of new policies. The Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform of Act of 2006 promises changes to both FEMA and DHS that will improve emergency preparedness in the future. After the disaster, a new administrator was appointed to FEMA. This new administrator has emergency management experience, which is one of the provisions in the previously mentioned reform act. The act also mandates that the head of FEMA “will have direct communication access to the Congress and to the president in a time of emergency” (Miller, 2012). The act is seen as a shift back towards preparedness instead of just recovery Chapter 9 Summary Hurricane Katrina proved to be one of the largest natural disasters that the United States has ever had. It showed many inadequacies in both the emergency preparedness plans and responses to the disaster at local, state, and national levels. The nation learned important lessons about how to effectively plan for future disasters, and what parts of communication and public health need to be improved in order to function more seamlessly. Even with these challenges, the recovery efforts were unprecedented, with various volunteers, donations from non-profit organizations, and the tireless work of law enforcement. Subsequent policies hope to close the gaps in the emergency response system so that the government can be more coordinated in future events. 12 HURRICANE KATRINA Chapter 10 Recommendations Although the federal government has taken much of the blame for the Hurricane Katrina crisis, I think that greater local and state government involvement in emergency preparedness could have helped immensely in this situation. As noted before, police powers are assigned to the states. They carry the responsibility of protecting the health and safety of their citizens. Obvious problems within Louisiana’s levee system were noted before the hurricane, but no action as taken to fix them. Also, the states most affected by the hurricane had some of the worst public health infrastructures in the country. I would recommend that local and state officials in this area, along with all states, take action to write emergency preparedness and response policies. Unlike the federal government, the state government is able to focus its policies to the specific needs of that community. Each state should not only create its own emergency preparedness and response plans, but also carry out drills to make sure that these plans can be implemented successfully at the time of a disaster. Local and state public health agencies are knowledgeable about emergency preparedness, and well suited to make plans for the states. Public health agencies can also make sure that public health and medical aid will be in place in the event of a crisis. 13 HURRICANE KATRINA References Fritz, H. M., Blount, C., Sokoloski, R., Singleton, J., Fuggle, A., McAdoo, B. G., & ... Tate, B. (2008). Hurricane Katrina Storm Surge Reconnaissance. Journal Of Geotechnical & Geoenvironmental Engineering, 134(5), 644-656. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241(2008)134:5(644) Kelman, I. (2007). Hurricane Katrina disaster diplomacy. Disasters, 31(3), 288-309. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7717.2007.01010.x Miller, L. M. (2012). Controlling disasters: recognising latent goals after Hurricane Katrina. Disasters, 36(1), 122-139. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7717.2011.01244.x Parker, C. F., Stern, E. K., Paglia, E., & Brown, C. (2009). Preventable Catastrophe? The Hurricane Katrina Disaster Revisited. Journal Of Contingencies & Crisis Management, 17(4), 206-220. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5973.2009.00588.x Plitt, S., & Maldonado, D. (2012). When Constitutional Challenges to State Cancellation Moratoriums Enacted After Catastrophic Hurricanes Fail: A Call for a New Federal Insurance Program. BYU Journal Of Public Law, 27(1), 41-96. Shughart, I. F. (2011). Disaster Relief as Bad Public Policy. Independent Review, 15(4), 519-539. Teitelbaum, J.B. & Wilensky, S. E. (2013). Essentials of health policy and law. United States of America: Jones and Bartlett Learning. The White House: President George Bush. (n.d.). The federal response to Hurricane Katrina: Lessons learned. Retrieved from http://georgewbushwhitehouse.archives.gov/reports/katrina-lessons-learned/ HURRICANE KATRINA 14