South Florida Sociocultural Systems SYD 6625 Fall 2012 Mondays

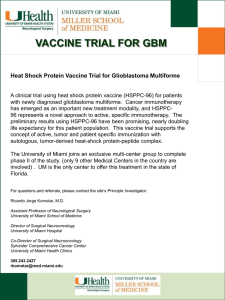

advertisement

South Florida Sociocultural Systems SYD 6625 Fall 2012 Mondays, 5-7:40 Instructor: Guillermo J. Grenier Office: SIPA 331 Phone: 305-348-3217 Course description: This course provides a graduate-level overview of the major social, political, economic, environmental and cultural forces at work in creating the Miami/South Florida area. From its incorporation on July 28, 1896, Miami lacked what real American cities possessed. Unlike northern cities like Chicago, Cincinnati or Pittsburgh, Miami was not a cross road city, growing at the breakpoints of railroads and water routes and attracting industrial capital. Nor did a seaport rapidly emerge to compete with New Orleans or the port cities on the East Coast. It’s an area that has never been fully southern or northern. Throughout most of its history, it’s been characterized by a large transient population and a large proportion of inhabitants who were first generation migrants. These and other characteristics have shaped what today many regard as a unique example of urban America. The metropolitan area of Miami (Miami-Dade County) has been referred to as a social experiment in progress. Some have called it the “Capital of Latin America.” Others regard it as a city at the center of some of the most important contemporary social processes reshaping the nation. Some consider it a harbinger of changes that are fueling passions and national debates. Others consider it a freak of modern history. In this course, we’ll explore the socioeconomic, political, cultural dynamics of metropolitan Miami in a socio/historical context. In this course, we’ll explore the socioeconomic, political, cultural dynamics of metropolitan Miami in a socio/historical context. We will pay particular attention to the processes involved changing the characteristics of 1) the people, 2) the culture, 3) the material environment, 4) the social organization and 5) the social institutions of the region. What you have to do. The course will focus on 1) the development of a “mini research project,” 2) the writing of a brief “conclusions” paper highlighting the most pertinent, err, conclusions from the project, and 3) the presentation of this project in class. Those of you working on dissertation research are encouraged to formulate projects which contextualize your research question using the Miami literature and social environment. Even if this does not carry over to your final dissertation work, it will offer you important insights on your topic. Others will formulate research questions based on interests and curiosity. In addition, you will complete an annotated bibliography each week from the assigned readings. This will help you develop your responses to the readings during our class discussions. When it’s all said and done, you will be familiar the major social forces at work in the creation of the modern South Florida region. We will take a trans-disciplinary view of the development of our region, reading literature with a Miami focus from across the social sciences. You will read from contemporary scholarship in anthropology, sociology, criminology, psychology and geography. You will be familiar with the perspectives of a broad, multi-disciplinary group of scholars studying the area that we think we know so well. We will discuss the methods to the madness of studying Miami as well critically examine the “state of the literature” in the field. You will be conversant with the key debates in the literature and evaluate how your research contributes to this literature. Responsibilities: You are responsible for completing all assigned readings ahead of the class period for which they are assigned. You are responsible for purchasing, borrowing, or downloading all assigned reading in time to read it. You are responsible for attending each and every scheduled seminar meeting. You are responsible for leading seminar discussion of at least one week’s readings (depending on enrollment, it could be two). You are responsible for meeting all deadlines. You are responsible for contributing meaningfully to every seminar meeting. You are responsible for respecting the views your classmates, your instructor, and the published scholars whose work you will read. You are responsible for completing all assigned readings, classroom activities, and projects when they are due. This goes for weekly readings as well as the “big three” assignments. By now you should know the drill on plagiarism: plagiarism and other instances of academic dishonesty simply will not be tolerated. There is “one strike” rule in effect. What to expect: This seminar will be about you actively participating through group discussions and investigation, and me actively listening and expanding on the discussion. I will try mightily to contribute without dominating. I have had a lot of experience doing research in Miami and thinking about how Miami works so I might kick off our sessions with an update on the readings, when that’s required or otherwise frame the context of the readings. The bulk of the class meetings in weeks 2-13 will involve student-led discussion of the week’s readings, centering on the focus questions. Weeks 15 and 16 will center on presentation and discussion of your mini research projects. Grades: An A is yours to lose. To keep it, this is what you do: come to every session; read all of the readings; contribute significantly to our discussions; write in grammatically comprehensible and empirically accurate prose; take your role as discussion leader seriously and don’t talk unprepared crap; meet the deadlines and take every assignment seriously; make connections between the weekly readings and the main themes of the class. If you do all of the above, you have an A. An A- can be earned from minor shortcomings in one of the areas mentioned above. Grades in the B range (B+, B, B-) arise from several unexplained absences, little class participation, major deadline failures, or a demonstrated inability to connect work and discussion to the themes of the course. Grades in the “C” range are rarely assigned. Receiving such a grade should not come as a surprise. You will see the sad face in many of my e-mails to you. If you totally blow the mini project plus have many absences and are frequently mistaken for a corpse during class time you will surely get a C. Your grade is composed of the following: Mini research project: 50 Discussion leading: 10 Annotated bibliography: 20 Participation (includes attendance): 20 Total 100 Mini research project: Step 1: Develop, or work with your existing, research questions and chose a research a research site/strategy. What are your research questions? What methodology will you use to address them? What literature contributes to your understanding of your topic? Select a research setting on which you can carry out a mini project and go to it. Due: 2 copies in-class, September 12 Worth: 5 points Step 2: Mini-proposal. A very brief proposal consists of four sections: I: Statement of your research topic; II: Research question; III: Identify your methodology and outline research steps, and IV: State the broader relevance of your project. Due: 2 copies in-class, Sept. 26 Worth: 10 points Note: If you haven’t done so by now, you will need to put in an IRB application to conduct this work, and it must be approved by the IRB before you can conduct your research. I will assist you with this process. Step 3: Conduct Field research. Use one of the qualitative or quantitative techniques that you’ve learned to conduct research (interviews, focus group, participant observation, secondary data). Bring raw materials and typed-up versions of data to class Due: 2 copies in-class, October 31 Worth: 15 points Step 4: Interpretation in form of Conclusions: Interpret your data and come up with preliminary conclusions about your research question. Make it brief: about five double-spaced pages. Write it as you would write a concluding section of an article. Remind us of your research questions, summarize the results and indicate how this supports, debunks or initiates new avenues for research. Due: 1 copy in-class, November 21 Worth: 15 points Step 5: In-class presentation and delivery of materials: Prepare a brief presentation (time limits TBA and determined by number of students) to be delivered in class. Assemble all of your materials, along with any supplemental materials you like – photographs or anything else that might be relevant or useful – into a portfolio. Due: In-class presentation dates TBD, mini research project portfolio hard copy due December 2 in my box by 5:00 PM. Worth: 10 points Discussion leading (10): at our first meeting, I will pass around a sign-up sheet and you will choose a week to serve as the discussion leader. You develop three or four questions which can be used in class to explore the importance of the readings. Questions should encourage seminar participants to identify themes of the reading themes, provoke discussion, and/or connect to larger or recurring issues in the class overall. In class, you will provide an overview of the readings, and facilitate the discussion. Annotated bibliography (20): every week, you will write up a summary of all assigned readings for that week. Annotated bibliography entries should average one typed page per journal article or chapter, and three per book. The annotations should include 1) a summary of research questions that the article/book attempts to answer or clarify, 2) the methodology used to address the questions, 3) the conclusions and contributions made to the research and 4) your own brief assessment of the reading. You will turn this in to me in Week 15. Participation (20): Come to every class, be on time, and contribute meaningfully to the discussions. Those who do all of these receive full credit; those who do not will experience grade erosion. READING LIST Books (Most of these books can be purchased used) Shell-Weiss, Melanie. 2009. Coming to Miami: A Social History. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. Nijman, Jan. 2010. Miami : Mistress of the Americas. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Stepick, Alex, Guillermo Grenier, Max Castro, Marvin Dunn. 2003. This Land is Our Land: Immigrants and Power in Miami. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. Grenier, Guillermo and Lisandro Perez. 2003. The Legacy of Exile: Cubans in the United States. New York: Allyn and Bacon. Dunn, Marvin. 1997. Black Miami in the Twentieth Century. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. Croucher, Sheila. 1997. Imagining Miami: Ethnic Politics in a Postmodern World. Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia. Stepick, Alex. 1997. Pride Against Prejudice: Haitians in the United States. New York. Allyn and Bacon. Garcia, Maria Cristina. 1996. Havana, U.S.A.: Cuban Exiles and Cuban Americans in South Florida, 1959-1994. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. Portes, Alejandro and Alex Stepick. 1993. City on the Edge: The Transformation of Miami. Berkeley, California; University of California Press. Grenier, Guillermo, Alex Stepick (Eds.). 1992. Miami Now! Immigration, Ethnicity and Social Change. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. Porter, Bruce and Marvin Dunn. 1984. The Miami Riot of 1980: Crossing the Bounds. Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books. Recommended Readings Didio, Joan. 1998. Miami. New York. Vintage. Allman, T.D. 1988. Miami: City of the Future. New York: Grove/Atlantic. Week 1: Introduction to the Class/Discussion Leaders Assigned/Library Study Guide Week 2: The Miami School? Lutters, Wayne G. and Mark S. Ackerman, 1996. An Introduction to the Chicago School of Sociology. (manuscript) Deegan, Mary Jo. 2001. The Chicago School of Ethnography. Handbook of Ethnography. Edited by Paul Atkinson, Amanda Coffey, Sara Delamonte, John Lofland, and Lyn Lofland. Londond: Sage. 11-25. Dear, Michael. 2002. Los Angeles and the Chicago School: Invitation to a Debate. City & Community. 1 (1): 5-32. Heaney, Michael and John Mark Hansen, 2006. Building the Chicago School. American Political Science Review. 100 (4): 589-595. Grenier, Guillermo and Alex Stepick. “Introduction.” Miami Now! Miami Now! Immigration, Ethnicity and Social Change. Guillermo J. Grenier and Alex Stepick, Editors. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. Pp.1-17. Nature and Society Week 3: No Class/Labor Day Week 4: The Rise of Miami History of Coral Gables on our Study Guide site Shell-Weiss, Melanie. 2009. Coming to Miami: A Social History. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. Sassen, Saskia and Alejandro Portes. 1993. Miami: A New Global City? Contemporary Sociology 22 (4):471-477. Nijman, Jan. 2000. The Paradigmatic City. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 90 (1): 135-145. Week 5: (Un)Natural Setting Nijman, Jan. 2010. Miami : Mistress of the Americas. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Ogden, Laura. 2008. The Everglades Ecosystem and the Politics of Nature. American Anthropologist, Vol. 110, Issue 1. Pp. 21-32. Ogden, Laura. 2008. Searching for Paradise in the Florida Everglades. Cultural Geographies 15:207-229. Hollander, Gail. 2010. Power is sweet: Sugarcane in the global ethanol assemblage. The Journal of Peasant Studies 37 (4): 699,699-721. Week 6: Who Built Miami? Dunn, Marvin. 1997. Black Miami in the Twentieth Century. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. Porter, Bruce and Marvin Dunn. 1984. The Miami Riot of 1980: Crossing the Bounds. Lexington, Mass.: Lexington Books. Bowie, Stan L., and Alex Stepick. 1998. Diversity and division: Ethnicity and the history of miami. Research in Urban Policy 7 : 19,19-32. Grenier, Guillermo J., and Max J. Castro. 1998. The emergence of an adversarial relation: Blackcuban relations in miami, 1959-1998. Research in Urban Policy 7 : 33,33-55. Migration and Diasporas Week 7: Strangers at the Gate Grenier, Guillermo, Alex Stepick (Eds.). 1992. Miami Now! Immigration, Ethnicity and Social Change. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. Huntington, Samuel P. 2004. The hispanic challenge. Foreign Policy(141): 30,30-45. Massey, Douglas S. 1979. Effects of socioeconomic factors on the residential segregation of blacks and spanish americans in U.S. urbanized areas. American Sociological Review 44 (6): 1015,1015-1022. Portes, Alejandro, and Min Zhou. 1992. Gaining the upper hand: Economic mobility among immigrant and domestic minorities. Ethnic and Racial Studies 15 (4): 491,491-522. Week 8: Frontier City Blues Portes, Alejandro and Alex Stepick. 1993. City on the Edge: The Transformation of Miami. Berkeley, California; University of California Press. Portes, Alejandro. 1985. Ethnics and exiles: Divergent tales. Contemporary Sociology 14 (6): 670,670-673. Portes, Alejandro, and Steven Shafer. 2007. Revisiting the enclave hypothesis: Miami twentyfive years later. Research in the Sociology of Organizations 25 (0733-558): 157,157-190. Week 9: “The Cubans are Taking Over” Grenier, Guillermo and Lisandro Perez. 2003. The Legacy of Exile: Cubans in the United States. New York: Allyn and Bacon. Garcia, Maria Cristina. 1996. Havana, U.S.A.: Cuban Exiles and Cuban Americans in South Florida, 1959-1994. Berkeley, California: University of California Press Eckstein, Susan, and Lorena Barberia. 2002. Grounding immigrant generations in history: Cuban americans and their transnational ties. The International Migration Review 36 (3): 799,799-837. Week 10: Divergent Fates Stepick, Alex. 1997. Pride Against Prejudice: Haitians in the United States. New York. Allyn and Bacon. Little, Cheryl. 1999. Inter Group coalitions and immigration politics: The haitian experience in florida. University of Miami Law Review 53 (4): 717,717-741. Mohl, Raymond A. 1985. An ethnic "boiling pot": Cubans and haitians in miami. The Journal of Ethnic Studies 13 (2): 51,51-74. Rey, Terry. 2004. Marian devotion at a haitian catholic parish in miami: The feast of our lady of perpetual help. Journal of Contemporary Religion 19 (3): 353,353-374. Week 11: Contextualizing Power Stepick, Alex, Guillermo Grenier, Max Castro, Marvin Dunn. 2003. This Land is Our Land: Immigrants and Power in Miami. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. Concha, Pat, Lourdes Garcia, and Ana Perez. 1975. Cooperation 'versus' competition: A comparison of anglo-american and cuban-american youngsters in miami. Journal of Social Psychology 95 : 273-. Grenier, Guillermo, and Bruce Nissen. 2000. Comparative union responses to mass immigration: Evidence from an immigrant city. Critical Sociology 26 (1-2): 82,82-105. Week 12: Deviance and Culture Alpert, Geoffrey P., Roger G. Dunham, and Michael R. Smith. 2007. Investigating Racial Profiling by the Miami-Dade Police Department: A Multimethod Approach. Criminology & Public Policy 6 (1): 25,25-55. Lee, Matthew T., and Ramiro Martinez. 2002. Social disorganization revisited: Mapping the recent immigration and black homicide relationship in northern miami. Sociological Focus 35 (4): 363,363-380. Martinez, Ramiro. 1997. Homicide among miami's ethnic groups: Anglos, blacks, and latinos in the 1990s. Homicide Studies 1 (1): 17,17-34. Eitle, David, and John Taylor. 2008. Are hispanics the new 'threat'? minority group threat and fear of crime in miami-dade county. Social Science Research 37 (4): 1102,1102-1115. Identities and Inequalities Week 13: On Civil Society Croucher, Sheila. 1997. Imagining Miami: Ethnic Politics in a Postmodern World. Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia. Alba, Richard D., John R. Logan, and Brian J. Stults. 2000. The changing neighborhood contexts of the immigrant metropolis. Social Forces 79 (2): 587,587-621. Price, Patricia L. 2007. Cohering culture on calle ocho: The pause and flow of latinidad. Globalizations 4 (1): 81,81-99. Price, Patricia L., Christopher Lukinbeal, Richard N. Gioioso, Daniel D. Arreola, Damian J. Fernandez, Timothy Ready and Maria de los Angeles Torres. 2011. Placing Latino Civic Engagement. Urban Geography. Volume 32, Number 2: 179-207. Week 14: Beyond Ethnicity Berkowitz, Dana, and Linda Liska Belgrave. 2010. "She works hard for the money": Drag queens and the management of their contradictory status of celebrity and marginality. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 39 (2): 159,159-186. Kurtz, Steven P. 2005. Post-circuit blues: Motivations and consequences of crystal meth use among gay men in miami. AIDS and Behavior 9 (1): 63,63-72. ———. 1999. Butterflies under cover: Cuban and puerto rican gay masculinities in miami. The Journal of Men's Studies 7 (3): 371,371-390. Pena, Susana. 2010. Gender and sexuality in latina-o miami: Documenting latina transsexual activists. Gender & History 22 (3): 755,755-772. Week 15: Presentations Week 16: Presentations