The Raven and the Crown: Ethnic Diversity and Political Legitimacy

advertisement

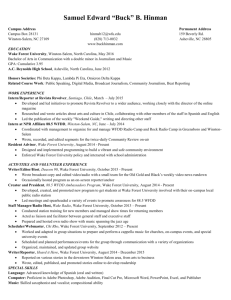

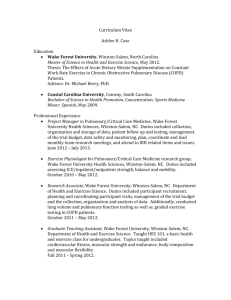

The Raven and the Crown: Ethnic Diversity and Political Legitimacy in the Reign of Matthias Corvinus Alexander Boston, History Honors Advisor: Monique O'Connell The image of Matthias Corvinus (1443-1490), Hungary’s only native-born king in a four hundred year span has been a rallying point for Hungarian nationalists since the 1840’s. Surprisingly, during his own lifetime, Matthias never portrayed himself as Hungarian. Instead, Matthias created a cosmopolitan image more akin to Renaissance princes of Italy and France drawing heavily from Classical themes. The Hungarian kingdom at the time stretched from Croatia to Transylvania and from Bohemia to Belgrade, Serbia, comprising a host of ethnic and religious groups that were for centuries before and since in almost constant conflict. Although source limitations make certainty impossible, I argue that the widespread policy changes instigated by Matthias were purposefully coordinated. His decisions all appear to reflect an awareness of the contemporary ethnic divisions and seek to overcome these divisions through disseminating a common culture, economy, judiciary, and military. In addition, the policy and patronage decisions appear to reflect the same underlying Renaissance philosophy. As a result, the multitudes of ethnicities present in Hungary not only remained loyal to Matthias throughout his reign, but appear to have considered themselves Hungarian. The paper prompts questions about how politicians may, through coordinated economic, cultural, and military policy strategies, learn from Matthias’ example to unite divided nations. Future plans: I will be attending Wake Forest University School of Law. The Political Reasoning behind Kwame Nkrumah’s continued Promotion of PanAfricanism following Ghana’s Independence: 1957-1966 Michael Byington, History Honors Advisors: Nathan Plageman and Anthony Parent In 1957, Kwame Nkrumah led Ghana to its independence from British colonial rule. In the years that followed, the new Prime Minister continued to advocate for a single, unified African government in a movement known as Pan-Africanism. This paper explores why Nkrumah so vigorously pursued Pan-Africanism following Ghana’s independence. Historians agree that the most rational interpretation of Nkrumah’s continued support of Pan-Africanism is that he feared European-induced neo-colonialism. But a more careful review of reports written by nonGhanaians, British trade directories, and Nkrumah’s own words demonstrates that Ghana’s leader was also apprehensive about the actions of other newly independent African states. Nkrumah believed Pan-Africanism was the means by which he could protect the political and economic interests of Ghanaians from both external empires and African nations. His continued advocacy of Pan-Africanism demonstrates that he was neither a Pan-African hero nor Ghanaian tyrant but rather an overly ambitious leader of a newly liberated nation. More importantly, his actions demonstrate why Pan-Africanism failed. On the one hand, Nkrumah’s notion of the movement gave undue privilege to Ghana at the expense of other African states. While Africans shared the common concern of neo-colonialism, the leaders of newly independent African nations did not want to relinquish their national sovereignty to a continental body under Nkrumah’s direction. Pan-Africanism, as proposed by Nkrumah, was impossible despite the many political and economic benefits it might have held for Ghana or the continent as a whole. Future plans: While I intend to eventually attend law school, I am moving to Denver this summer to take part in an internship with the Denver Nuggets basketball team. "Winston-Salem had its Mob": Textiles, Tobacco, and Race in the Industrial South Eleanor Davidson, History Honors Advisor: Michele Gillespie Winston-Salem’s early twentieth century industrialization caused tension between white textile mill workers and Richard J. Reynolds’s black tobacco workers, culminating to a race riot six days after Armistice that interrupted the seemingly calm racial climate that had prevailed during the war. The alleged rape of a white woman by a black assailant sparked an outbreak of violence from textile workers who attempted to kidnap and lynch the accused man. Civic and industrial leaders downplayed the event, which reached a national audience, and the local justice system actually prosecuted white perpetrators to return the city to racial harmony and economic productivity. In reaction to the riot, city leadership and business elite promoted and maintained Winston-Salem’s “New South” reputation as a city void of race problems and favorable to industrial progress. In so doing they perpetuated a paternalistic system of class and race-based discrimination that kept wages low and labor sympathy splintered. The Ascendancy of Girolamo Savonarola in 15th Century Florence William McClure, History Honors Advisors: Monique O'Connell and Paul Escott Savonarola’s rule of Florence from 1494 to 1498 is a unique episode in Florentine history and in the progression of the Renaissance. Espousing moral virtue, he attacked what he perceived as the vanities produced by the Florentine culture yet also instituted republican reforms which permitted citizens greater agency over their society. Though the current scholarship is deep on the actions of Savonarola and much attention is given to his motivations, there is not yet a comprehensive understanding of how he gained and maintained power during this period. Drawing heavily from his sermons, correspondences, and accounts and critiques written by his contemporaries, this paper argues that Savonarola rose to power through three specific means. It concurs with arguments previously set forth that Savonarola gained power by attacking the previous oligarchic government of the Medici and by capitalizing on the general disgust with the papacy and Church bureaucracy. However, this paper adds the previously unmentioned argument that Savonarola also effectively appealed to and integrated the disaffected young men of Florence into his movement. In setting forth these three components of Savonarola’s rise to power as well as maintenance of de facto leadership, this paper adds to the scholarship about Savonarola and this period of Florence and contributes to future research projects on this topic. Future plans: I am excited to begin my life outside of Wake Forest with a position in AT&T corporate sales. I am so thankful for all of the opportunities for academic and personal growth that have been afforded me in my time at Wake. From Empire to Neighborhood: Latin America In U.S. Foreign Relations from 1898 to 1937 Matthew Moran, History Honors Advisors: Simone Caron and John Hayes This paper explores the changing relationship between the United States and Latin America throughout the first half of the 20th century. Beginning with the Spanish-American War in 1898, the paper traces how a foreign policy of imperial control evolved into one of limited intervention, only to be replaced with a policy of restraint and cooperation under President Franklin Roosevelt. This paper further argues that the main factor behind this evolution was not a change in the business or security communities, but rather a shift in how Americans viewed the use of force and the role of the United States in the hemisphere. This challenges a prevailing wisdom that argues that foreign policy is the result solely of economic motivations or security concerns and introduces ideas and culture as important elements of understanding a state’s policies abroad. Future plans: Working in public relations in New York City. “We Called Ourselves ‘Revolutionaries’”: Remembering Integration at Wake Forest University Margaret Wood, History Honors Advisor: Michele Gillespie On May 18, 1962, Edward Reynolds was admitted to Wake Forest College for the fall term of 1962 as a full-time undergraduate student. Reynolds’s admission signaled an end to racial segregation in the undergraduate school at Wake Forest. While Wake Forest University was the first prominent, private, Southern college to integrate, the public memory created of the university’s integration is very narrow. This thesis seeks to reconcile some of this memory by recognizing the struggles of students who helped integrate Wake Forest. It scrutinizes the impetuses behind Wake Forest’s integration, the federally-mandated desegregation at the University of Georgia, the integrations at Tulane University, Duke University, Emory University, Vanderbilt University, and Rice University as elite, private Southern colleges, and the parallel motivations of Wake Forest’s sister Baptist institution, Mercer University. The connections between Wake Forest, the University of Georgia, Tulane, Duke, Emory, Vanderbilt, Rice, and Mercer are evidence of a network of influence among all Southern schools as pressure to integrate climaxed in the 1960’s. It determines that, while Tulane, Duke, Emory, Vanderbilt and Rice were moved to integrate by a desire for national prestige and the finances needed to attain that national prestige, Wake Forest’s motivations to integrate seem to have largely been driven by student, faculty, and administrative moral, Baptist imperative. Telling the story of integration at Wake Forest University is important to ameliorate race relations by relating to and relieving the resentment of students at all universities whose stories of integration have not been publicly shared. Future plans: I plan on getting my master's degree in international relations and to eventually attend law school. I hope to one day practice international law.