Virtual IEP meetings

advertisement

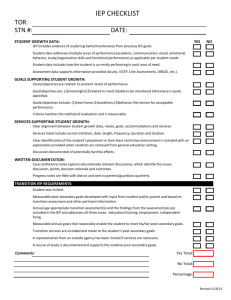

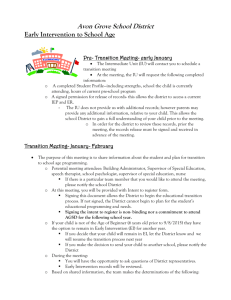

Getting Families Involved: The Art of Virtual IEP Meetings Getting Families Involved: The Art of Virtual IEP Meetings Intro Emily is a 14-year old girl in eighth grade that has been diagnosed with Asperger syndrome and Dyslexia. Prior to entering the public school system last year, she was unable to read and write. Now, she is reading at a second grade level and completing small writing assignments. Her progress is the result of collaboration between parents, special educators, general educators, and related service providers. Unfortunately, many students with disabilities are not provided with the familial and academic supports necessary to succeed. Individualized planning teams are designed to help children meet their goals, but it is suggested that parents and students provide the least amount of input throughout the process (Childre, 2005; Dabokowski, 2004). Families can provide important personal information about students, which is needed to create individualized education plans focusing on all aspects of student achievement (Lytle & Bordin, 2001). How can teachers and related professionals encourage families to be more active in the IEP process? The answer is quite simple: communicate. Communication between educators and families is a key component in compiling relevant data and creating appropriate goals for the student. The team must be cognizant of the circumstances and needs of the family. In traditional meetings, the team member who communicates least is the student. Involving students and parents in the process requires a change in the structure of the team, and a more student-focused approach (Kroeger, Leibold, & Ryan, 1999). This article will examine the infrastructure of student-led IEP meetings in virtual environments. It begins by clearly defining the roles of IEP team members and explains how each team members’ involvement is crucial to student success. Next, it focuses on student Getting Families Involved: The Art of Virtual IEP Meetings centered planning and the benefits of student-led IEP meetings. Finally, recommendations for how to empower students in online settings are discussed. The Role of IEP Teams The purpose of an IEP team is for all team members to collaborate and communicate in the interest of developing a plan that meets the needs of an individual child. For this to happen all team members should be present and provide input about the student. As Lytle and Bordin (2001) define it, “an IEP team consists of the parents, an administrator, a general education teacher, and special education staff” (p. 40). However, it is important to discuss what makes the process a team effort. While it is necessary to have the students’ success as a common goal, it is not enough to create a team. Problems arise because team members do not know the specific responsibilities of their role at the meeting or they misunderstand the roles of others. Often, parents and students do not realize how crucial their role is in developing the IEP. The first step in creating a successful team is to clearly define the roles of each person that will be present. An administrator is always invited to serve as the Local Education Agency (LEA) representative, and is present as an informant if they know the child personally. Depending on the grade level and departments that the administrator oversees, he or she could be an asset to the meeting by providing information about supplemental programs and activities at the students’ grade level or information about tutoring and counseling services. In a traditional meeting, administrative input is often negative, and their presence is one of intimidation or mediation. At times, this is the parent and student’s first interaction with the school administrator and positivity should be encouraged to foster a lasting and fruitful relationship between the home and school environments. Getting Families Involved: The Art of Virtual IEP Meetings It is suggested that school counselors could play a vital role in IEP meetings. Counselors could offer ideas to students for transition planning beyond the middle and high school classrooms. Strengths-based school counseling is one way to create a more person centered IEP. Traditional approaches to the IEP process focus on student deficits in goal creation and suggested accommodation and modifications, but strength based services incorporate areas where students show strength and gains. While students in middle grades seek autonomy and independence, adult encouragement is still needed to thrive academically. Consider the following scenario: Jonathan, an eighth grade student, received a good score on his last English paper, and his expectation is that his teacher will praise him for it. What happens when she comments on his lack of grammatical correctness instead of his excellent organization and content? Focusing on student strengths, not only builds confidence in the student, but creates a positive climate for , parent and educator input. In Geltner’s (2008) view, “the SBSC approach values family perspectives allowing for a more holistic picture to be painted by all involved with the child” (pg. 163). Viewing all aspects of students’ lives is a crucial component in the IEP process, because it provides the team with an academic, social, and familial snapshot with which to work. Both general and special educators are also present at all IEP team meetings. General educators share a common misconception that they are just there to provide input about how the student is performing in a particular course. However, general educators should be playing a much more active role by providing suggestions for accommodations and modifications for the student and letting team members know which specifically designed instructional components are most effective and why. Educators should contribute significantly to the following IEP components: Getting Families Involved: The Art of Virtual IEP Meetings Student progress in the general education curriculum Effectiveness of supplemental programs and academic interventions Social participation and development Suggested instruction modifications to make the general education curriculum accessible Identification of student strengths and weaknesses IEP Team Members Traditional Role Revised Responsibilities Administrator Mediate between parent and educators should an issue arise Provide input about beneficial supplemental programs or activities General Educator Provide updates on student performance Speak directly to the student and parent about class performance both positive and negative Special Educator Create the IEP using the recommendations of the team and expert knowledge of student history Develop an open line of communication with the parent and student that encourages active participation at the meeting Related Service Provider Treat the IEP as a living, breathing document and incorporate IEP team ideas and suggestions. Report recommendations and Discuss services with student and progress in the areas of speech, parent and ask for input from the occupational, physical, and other family regarding progress at home related therapies Counselor Provide input if the case is Focus on student strengths instead behavioral, social, or emotional in of deficits (Geltner & Leibforth, nature 2008) Parent Agree to attend the meeting and provide a minimal amount of information about the student Give information the team about student interests, hobbies, strengths, and weaknesses. Engage student in discussion. Getting Families Involved: The Art of Virtual IEP Meetings IEP Team Members Traditional Role Revised Responsibilities Student Listen to other team members speak about the IEP, grades, services, etc. Student should take an active role in the meeting and be encouraged to discuss his or her likes, dislikes, and reflections Transition Coordinator Offer ideas about the student’s future endeavors. Provide students with a plethora of choices for post-secondary consideration including but not limited to college and vocations, employment, and independent living. Traditional Versus Person-Centered Planning While the hope is that all participants will give substantial input and place considerable effort into the IEP process, it is important to reinforce the purpose of the meeting and how each member should conduct themselves. In “traditional” IEP meetings the process is led by professionals, usually adults, and is goal-oriented focusing on the creation of measurable annual goals and objectives as mandated by federal and state laws. However, person centered practices encourage participation by parents and students as well as professionals, and are designed to gain information that will be used to discover the best ways to meet the needs of the student (Keyes & Owens-Johnson, 2003). Person-centered planning also does not restrict participation to professionals, but invites friends and community members as well. The focus of a personcentered meeting is to build a plan for the student’s future (Meadan, Shelden, Appel, & DeCrazia, 2010). This practice is similar to the steps involved in creating a transition IEP. The IEP must be more than a plan for student success in kindergarten through twelfth grade and should begin to prepare students for transition to college and careers in grade eight. Person-centered planning also takes advantage of informal assessment and does rely solely on the reading of data from evaluation reports and individualized education plans. In this Getting Families Involved: The Art of Virtual IEP Meetings portion of the meeting educator, counselor, parent, and student input are highly valued because they provide an authentic view that possesses a clinical lens. Two common terms that appear in person-centered planning are “dream-driven” and “strengths-based.” Traditional IEPs are designed to help students in their deficit areas, but also to build areas of strength (Keyes, 2003). More often than not, the deficit areas are the emphasis of team member input. Traditional meetings are focused on procedure and regulation, whereas person-centered approaches favor student vision and self-advocacy. Beginning in grade eight students are invited to IEP meetings with a separate invitation from parents, and also receive a copy of the service agreement. Adolescence is a difficult time for students because they are struggling with the dichotomy between belonging to a socially acceptable peer group and developing their independence. Wang, Willet, Dishion, and Stormshak (2011) suggest that “healthy adolescent autonomy unfolds in an environment that is structured, that is contingent on daily routines, and that scaffolds adolescent self-determination of actions and decisions” (p. 1325). Meaningful participation by students relies on training in self-advocacy. In traditional standards, students would be provided with the structure of the meeting and told when they will be expected to provide input. However, the more beneficial and contemporary approach is for students to begin building self determination skills and leadership abilities at the onset of adolescence. This requires educating the students in ways to design and facilitate their own meetings (Martin & Van Dycke, 2006). Special education teachers can guide adolescent students by providing them with templates for each portion of the meeting: introduction of team members, why the meeting is being held, transition ideas, goal development, and accommodations, modifications, and specifically designed instruction (Hawbaker, 2007). Getting Families Involved: The Art of Virtual IEP Meetings Advocacy Communication Career Planning • Creating goals and objectives • Asking questions to IEP team members • Facilitating team roles • Using presentation skills such as tone of voice, posture, and body language • Thinking and planning for the future • Designing a transition plan Parents of students with disabilities have a similar experience as their children. According to Ruppar and Gafney (2011), “Special education teachers talk the most during the IEP meetings, and contribute 51% compared to teacher and parent participation at 23%. In addition, 33% of parent contributions were considered passive participation” (p. 12). Student Led IEP Meetings Building Self-Determination Strategies Student Planning and Training Getting Families Involved: The Art of Virtual IEP Meetings Empowering Parent Conclusion Representatives from all aspects of students’ lives should be actively contributing members of the IEP team. Administrators, educators, parents, therapists, psychologists, and most importantly, the student should collaborate to create an IEP that is used as a stepping stone to building the students’ desired futures. Person centered planning is the key to developing the most effective plan for students and focuses on students’ “wants, hopes, concerns, and dreams” (Meadan, Shelden, Appel, & DeCrazia, 2010, pg. 8). The transition to independent living, work environments, and college classrooms depends on providing students with disabilities with the right tools to get there on their own. Self-advocacy and self-determination are at the heart of student-led IEP team meetings. Students with disabilities deserve the opportunity to take part in the development of educational plans, which directly impact their lives by providing team members with as much information about themselves as time will permit. The plan is designed for the student, so why not allow students to contribute meaningfully to its creation. Through careful scaffolding and training students can become leaders despite the severity of the disability (Hawbaker, 2011). Parents of students’ with disabilities can take on a more professional role in the IEP process through advocacy for their child and encouragement in the student-led process. While Emily still struggles to learn to read, one thing has changed. When the family enrolled they were not receptive to teacher suggestions and wanted to protect Emily from the school system. They viewed school employees as the enemy. Now, the family is willing to Getting Families Involved: The Art of Virtual IEP Meetings negotiate. Not much, but a little. What changed? The family’s contributions changed because they were asked what they wanted for their daughter. Emily was asked how she learns best. Small improvements bring on big changes. References Childre, A., & Chambers, C. R. (2005). Family perceptions of student centered planning and IEP meetings. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 40, 217-233. Dabokowski, D. M. (2004). Encouraging active parent participation in IEP meetings. Teaching Exceptional Children, 36, 34-39. Geltner, J. A., & Leibforth, T. N. (2008). Advocacy in the IEP process: Strengths-based counseling in action. Professional School Counseling, 12, 162-165. Hawbaker, B. (2007). Student-led IEP meetings: Planning and implementation strategies. Teaching Exceptional Children Plus, 3(5), 1. Keyes, M. W., & Owens-Johnson, L. (2003). Developing person-centered IEPs. Intervention in School & Clinic, 38, 145-152. Kroeger, S. D., Leibold, C. K., & Ryan, B. (1999). Creating a sense of ownership in the IEP process. Teaching Exceptional Children, 32. Lytle, R. K., & Bordin, J. (2001). Enhancing the IEP team. Teaching Exceptional Children, 33, 40-45. Martin, J. E., Marshall, L. H., & Sale, P. (2004). A 3-year study of middle, junior high, and high school IEP meetings. Exceptional Children, 70, 285-297. Getting Families Involved: The Art of Virtual IEP Meetings Meadan, H., Shelden, D. L., Appel, K, & DeCrazia, R. L. (2010). Developing a long-term vision: A road map for student’s futures. Teaching Exceptional Children, 43, 8-14. Mitchell, V. J., Moening, J. H., & Panter, B. R.(2009). Student-led IEP meetings: Developing student leaders. Journal of the American Deafness & Rehabilitation Association, 230240. Muhlenhaupt, M. (2002). Family and school partnerships for IEP development. Journal of visual impairment and blindness, 96, 175-179. Ray, J. A., Pewitt-Kinder, J., & George, S. (2009). Partnering with families of children with special needs. YC: Young Children, 64, 16-22. Spann, S. J., Kohler, F. W., & Soenksen, D. (2003) Examining parents’ involvement in and perceptions of special education services: An interview with families in a parent support group. Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities, 18, 228-237. Staples, K. E., & Diliberto, J. A. Guidelines for successful parent involvement: Working with parents of students with disabilities. Teaching Exceptional Children, 42, 58-63. Stroggilos, V., & Xanthacou, Y. (2006). Collaborative IEPs for the education of pupils with Profound and multiple learning difficulties. European Journal of Special Needs Getting Families Involved: The Art of Virtual IEP Meetings Education, 21, 339-349. Wang, M., Dishion, T. J., Stormshak, E. A., & Willett, J. B. (2011). Trajectories of family management practices and early adolescent behavioral outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 47(5), 1324-1341.