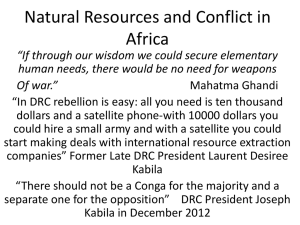

`Blessing` and `Curse` of Mineral Wealth in the Congo

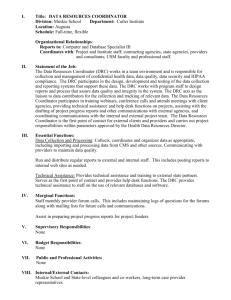

advertisement