Tips--Active Reading

advertisement

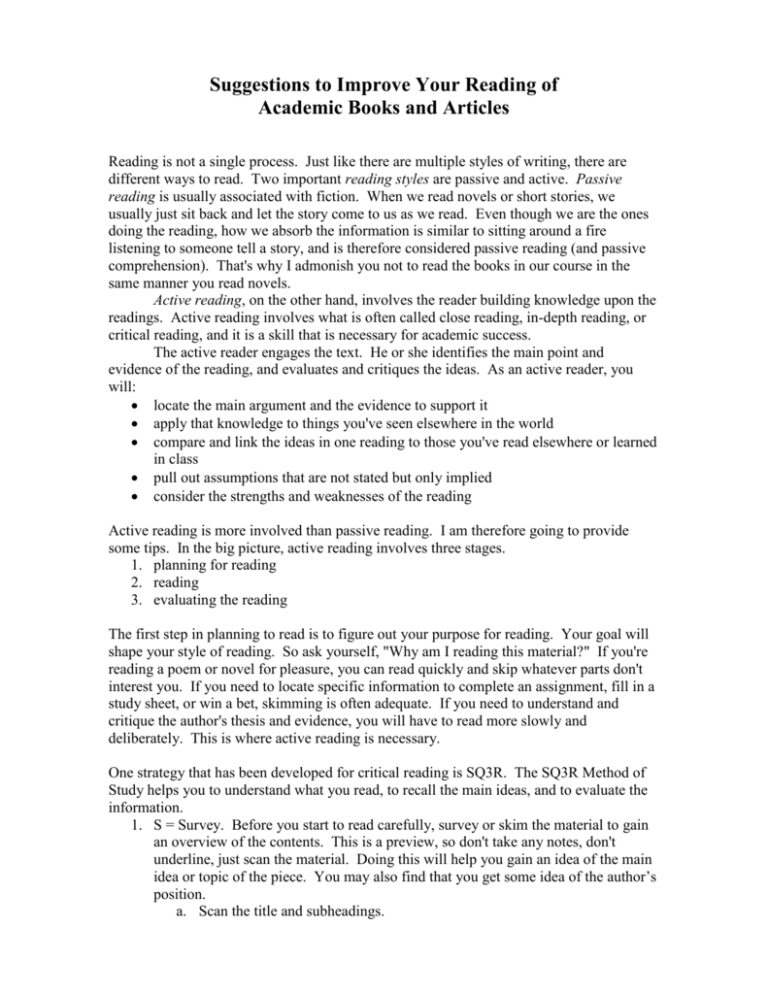

Suggestions to Improve Your Reading of Academic Books and Articles Reading is not a single process. Just like there are multiple styles of writing, there are different ways to read. Two important reading styles are passive and active. Passive reading is usually associated with fiction. When we read novels or short stories, we usually just sit back and let the story come to us as we read. Even though we are the ones doing the reading, how we absorb the information is similar to sitting around a fire listening to someone tell a story, and is therefore considered passive reading (and passive comprehension). That's why I admonish you not to read the books in our course in the same manner you read novels. Active reading, on the other hand, involves the reader building knowledge upon the readings. Active reading involves what is often called close reading, in-depth reading, or critical reading, and it is a skill that is necessary for academic success. The active reader engages the text. He or she identifies the main point and evidence of the reading, and evaluates and critiques the ideas. As an active reader, you will: locate the main argument and the evidence to support it apply that knowledge to things you've seen elsewhere in the world compare and link the ideas in one reading to those you've read elsewhere or learned in class pull out assumptions that are not stated but only implied consider the strengths and weaknesses of the reading Active reading is more involved than passive reading. I am therefore going to provide some tips. In the big picture, active reading involves three stages. 1. planning for reading 2. reading 3. evaluating the reading The first step in planning to read is to figure out your purpose for reading. Your goal will shape your style of reading. So ask yourself, "Why am I reading this material?" If you're reading a poem or novel for pleasure, you can read quickly and skip whatever parts don't interest you. If you need to locate specific information to complete an assignment, fill in a study sheet, or win a bet, skimming is often adequate. If you need to understand and critique the author's thesis and evidence, you will have to read more slowly and deliberately. This is where active reading is necessary. One strategy that has been developed for critical reading is SQ3R. The SQ3R Method of Study helps you to understand what you read, to recall the main ideas, and to evaluate the information. 1. S = Survey. Before you start to read carefully, survey or skim the material to gain an overview of the contents. This is a preview, so don't take any notes, don't underline, just scan the material. Doing this will help you gain an idea of the main idea or topic of the piece. You may also find that you get some idea of the author’s position. a. Scan the title and subheadings. b. Read the summary, abstract, or introduction. c. Note any lists, pictures, graphs, or charts. 2. Q = Questions. a. Some questions will focus your own reading. i. Think about specific questions that you need to or would like to find answers for. For instance, is there an assignment that provides you with specific questions? Or are you trying to find the author's main position? ii. Read any focus questions at the end of the reading. iii. Turn the title and subheadings into questions. For example, if the heading is "Qualitative and Quantitative Research," your question might be: "What is the difference between these two types of research?" b. Other questions will help you understand the author's position and background. i. Does the author appear to have a particular philosophy, ideology, or bias? ii. Is the author defending a particular point of view? Or is the author summarizing many different views (as is often the case with textbooks)?For whom is the material intended? iii. How does the author's argument or perspective relate to other material in the course or field? 3. R1 = Read. Be prepared to read material twice. a. Focus your reading before you even start. In other words, read with a purpose--have an idea of the information you are looking for before you begin reading. b. While reading, find and record important information. i. Look for patterns in the author's argument. Authors usually repeat their main point. ii. Circle important terms, people, and dates. iii. Underline or highlight the main points, or thesis, of each section. iv. Write in the margin "thesis" when you find it. v. Underline or highlight information that supports the thesis or the author's position. vi. Write questions or comments in the margins. This can include contradictions, your criticisms, how this relates to other readings or assignments, and so on. (This habit of writing in the books is a great way to consciously engage the readings. It's almost as though you will be having a conversation or debate with the author.) vii. Also take notes on separate paper on terms, definitions, theories, and other important ideas. Identify major and minor arguments and the supporting evidence. (Some people prefer to do this at the end of each section rather than while reading. You should use whatever approach you find most useful.) 1. Always record bibliographical details of the text from which you are taking notes. 2. Write on one side of the paper only. 3. Leave a wide margin for comments and cross-references. 4. Use headings, subheadings, and diagrams. 5. Keep notes brief but full enough to still make sense to you in six months' time. Make sure they're legible. viii. Write a brief summary of each section, which can often be a quote. c. Handle difficulties with sensible strategies and try not to get flustered when you get confused. i. Reduce your reading speed for difficult passages. ii. Stop and reread parts which are not clear. iii. Look up difficult words in the dictionary or glossary of terms and reread. iv. If the meaning of a word or passage still evades you, leave it and read on. Perhaps after more reading you will find it more accessible and the meaning will become clear. v. Use personal experience as a logical tool or memory aid. vi. Ask your instructor or classmates questions if you are still confused. 4. R2 = Recall. You should now try to recall what you have read. a. Close the book and write down the main points and evidence you remember. Then check their accuracy against the highlights and notes you made during your reading. Try doing the same thing after a few days. It can also be helpful to recite ideas aloud to help you remember. 5. R3 = Review. Read through your notes to reacquaint yourself with the main points. a. Critique and evaluate the readings while you are reviewing your notes. i. Has the author answered the questions you started with? ii. What parts do you agree or disagree with? Why do you disagree with the author? Is your position more sound or logical than the authors? iii. Were there confusing parts or contradictions? iv. Is the author's argument or presentation logical and consistent? v. Has the writer backed up statements and ideas with credible evidence? What is the quality of the evidence? vi. What assumptions did the author base her or his argument? vii. What aspects of the issue has the author ignored or omitted? viii. Does the writer present different sides of a case evenhandedly? Written by Dr. Casey Welch, 2010