DCN SuDs consultation response

advertisement

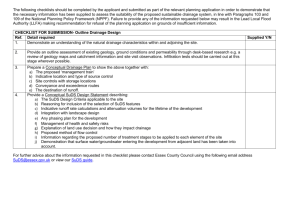

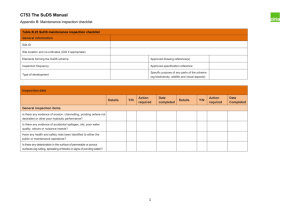

District Councils’ Network Response to ‘Delivering Sustainable Drainage Systems’ consultation – Sept/ Oct 2014 Sent by email to: suds@defra.gsi.gov.uk About our Organisation The District Councils’ Network (DCN) is a cross-party member led network of 200 district councils. We are a Special Interest Group of the Local Government Association (LGA), and provide a single voice for district councils within the LGA. We lobby central government, the political parties and other stakeholders directly on behalf of our members, as well as commissioning research, providing support, and sharing best practice. We welcome the opportunity to respond to this consultation and make this submission on behalf of our member authorities. To discuss this submission further please contact Jerry Unsworth, DCN Planning Project Officer, jerry@unsworthplanning.co.uk or Catherine Evans, DCN Manager, catherine.evans@local.gov.uk Summary of the DCN’s position A key concern with the consultation proposals is the longer-term maintenance and management of SuDS and funding arrangements. Whilst it is sensible to coordinate overall design of SuDS with the planning process we consider that the planning system is not suited to the detailed technical approval, adoption, enforcement and maintenance sides. We are concerned about liabilities and responsibilities for management and maintenance falling back on local authorities. We are concerned that the regime would add significant cost and staffing demands on local councils. If the proposals are pursued this will need to be addressed under the ‘new burdens’ doctrine. It appears that clear mandatory standards are needed. Inclusion in Planning Practice Guidance would mean that, as material considerations, they have to be balanced against other considerations that may take precedence. An inconsistent national approach on a critical issue is likely to emerge. It is evident that considerable further thought is needed to how the regime will operate so that a more robust solution is developed. The DCN will welcome involvement in how this is devised. We request that further consultation is undertaken on the finally preferred regime. The DCN Response to the Consultation Questions Q4. Do you agree that the proposed revision to planning policy would deliver sustainable drainage which will be maintained? If not, why? Q4 Summary NO – because of uncertainties around the approval, implementation and maintenance regime put forward. Whilst it is sensible to coordinate the overall design SuDS with the planning process, so site layout and design considerations are approached in an integrated way, we do not consider that the planning system (or District Councils generally) is suited to the detailed technical approval, enforcement of implementation (leading to adoption) and the long-term role envisaged. We consider that there should be a requirement for developers to comply with national standards and that a regime whereby the standards are ‘material considerations’ within planning guidance is unlikely to give them enough strength. A different regime is needed. Q4 Detailed comment Ensuring delivery requires inspection during construction - such as occurs under the Building Regulations. As a matter of course planners do not proactively check development as it is being constructed. This has significant implications for the proposal to use the planning regime. District Councils do not have the staff numbers to enable checking, regular inspection and if necessary enforcement / prosecution of each and every SuDS scheme in perpetuity. Experience of existing SuDS schemes by our member authorities suggests that to be effective SuDS schemes need inspecting on an annual basis and remedial maintenance action taken. Unless a requirement for such an inspection was introduced - critically with a cost recovery fee - then it could not be enforced through the planning regime. Also planning enforcement officers do not have the expertise to inspect and test SuDS schemes and a (funded) solution would be needed. The planning stage is frequently relatively early in the development process and we are concerned that it is not well suited to the level of construction detail that would be required for SuDS work. This is likely to lead to SuDS details being dealt with by planning condition to reduce the burden on the applicant, creating a new pressure on Local Planning Authorities (LPAs) to obtain detailed expertise and determine “details reserved by condition” applications on SuDS proposals within 8 weeks. The use of planning conditions has a number of risks and we would question whether it is the right mechanism for enforcing the long-term management and maintenance of SUDs schemes: - A Council may be expected to serve a Breach of Condition Notice upon a householder and ultimately take them to court if they fail to maintain the system. If a planning condition is breached for 10 years +, a council cannot enforce its requirements – with major implications for long-term maintenance. Experience suggests that when SuDS details are presently submitted they are rarely accompanied by all the information required by the Environment Page 2 of 7 District Councils’ Network October 2014 Agency (EA) or Lead Local Flood Authority (LLFA) and the information subsequently required can take considerable time to obtain. This could result in substandard SuDS proposals being accepted. If conditions are to feature we suggest model conditions are used (adapted when necessary) together with clear guidance on consultation arrangements, technical approval and what local planning authorities can expect in terms of advice. Any conditions would need to be immune from the proposed deemed discharge reforms set out in the recent technical consultation on planning. Also the Pitt Review stresses how important SuDS are in combating flooding. At the moment the NPPF requires a balancing of issues when determining a planning application and without very robust government guidance inadequate SuDS could be accepted as a necessary trade off to achieve a scheme that would not otherwise be delivered. The cost of SuDS in land take, construction cost and on-going maintenance will bring viability issues. The proposal lead to delivery of SuDS to larger sites (if adopted by a public body, such as a water authority) but we would highlight the implication for flood management of omitting what would prove to be a large number of smaller developments. As previously stated there is the question of inspection and enforcement. At the moment Local Authority planning officers are neither engineers, nor one of the many bodies already identified as having responsibility for drainage. So this proposal, while superficially attractive, appears unworkable in practice. Further consideration is also needed as to the role of the LLFA and the body that will assume responsibility for adoption/ maintenance to avoid overlaps/ misunderstandings. The inclusion of national standards for SuDs technical construction in the National Planning Policy Guidance is not considered the right approach. An alternative approach is needed. Consideration could be given to building regulations, with appropriate consultation. What is needed is a stable, fully funded and technically competent entity to deliver the on-going maintenance and management requirements of the installation over the lifetime of the development. This could be at least for a period of 50 years. Without this, maintenance could become very fragmented with a variety of authorities and management companies operating in one area. District Councils are not suited to this role. Q5. How should the Local Planning Authority obtain expert advice on sustainable drainage systems and their maintenance? What are the costs/benefits of different approaches? Q5 Summary One body, rather than a range, needs to be identified to assume a lead role. It would give clarity if this body assumed duties in relation to advice, technical approvals and enforcing maintenance. It is evident that considerable further thought is needed to how the regime will operate. Q5 Detailed comment Page 3 of 7 District Councils’ Network October 2014 There is a need for specialist technical advice, as local planning authorities do not have the expertise needed to consider the detail of the SuDS schemes submitted as part of a planning application. The consultation identifies 5 different bodies that potentially have to be consulted. We consider that there needs to be one, technically proficient, body given the effective power and responsibility with a duty to provide expert advice to local planning authorities on SuDS. In terms of options to deliver expertise we consider that there is benefit in the body that assumes maintenance/ enforcement powers being the same body that assumes the role to provide advisory/ expertise at the approval stage. This happens with highways. It may be that Water and Sewerage companies or LLFAs are preferred for assuming adoption and long-term maintenance role. We note that LLFAs have expertise, relevant responsibilities and have already received funds in relation to SuDS. Building control services could develop the necessary expertise to assess SuDS applications – funded through locally determined fee structures. Whichever body is decided upon it should be properly funded and become a statutory consultee, if schemes are to be approved in conjunction with the planning process. Although there is mention of the government undertaking a new burdens assessment it is not clear whether the applicant will have to pay an additional fee for funding the assessment of a SuDS scheme or whether the funding will come from elsewhere. As provision of SuDS is to be a ‘mainstream’ part of development it is appropriate that the costs should form part of the development cost. If a ‘conditions attached to planning permissions’ approach is followed then: - - In the first instance developers must be required (by guidance) to submit technically robust and sustainable SuDS solutions, based on sound and clear national guidance and standards. The guidance to developers should make clear that such a scheme should be supported by investigatory work and sufficient data with regards a robust design and maintenance regime. Pre-application advice should be sought an early stage by developers to ensure the relevant information is submitted. The assessment of this work will require the LPA to have access to expert advice – which they generally do not have. Consequently additional resources will need to be identified. The appointed body with responsibility for the technical overview and subsequent adoption/ enforcement of maintenance (not the District Council) will need to be able to discharge the requirements of any conditions, through the local planning authority. We suggest model conditions are used (adapted when necessary) together with clear guidance on consultation arrangements and what local planning authorities can expect in terms of advice. Any conditions should be immune from the proposed deemed discharge reforms set out in the recent technical consultation on planning. The aim must be to increase consistency, build knowledge and relationships with developers to ensure seamless development. Page 4 of 7 District Councils’ Network October 2014 It is evident that considerable further thought is needed to how the regime will operate. Q6. What are the impacts of different approaches for Local Planning Authorities to secure expert advice within the timescales set for determining planning applications? See answer to Q5 - Having to consult 4 or 5 different agencies will cause delay and confusion. One agency with the technical competence and comprehensive responsibility is required. Other (emerging) reforms to the planning system would add complexity/ problems e.g. return of fees at 26 weeks and possible deemed discharge of conditions when approval has not been given by the LPA. The consequence of these reforms would be that LPAs become reliant on the applicant’s agreement to extend periods for determination. Where that agreement cannot be reached this is likely to lead to the perverse situation of more refusals on the basis of lack of information and consequent delay. We are aware that external agencies/ advisors may not always be able to respond in time and design solutions may require re-notification of the proposals thus causing delays in processing. If the planning system is to be the vehicle for approving SuDS further thought needs to be given to the workability of the mechanisms. Q7. Do you agree that minor size developments be exempt from the proposed revision to the planning policy and guidance? Do you think thresholds should be higher? This is neither a simple YES nor NO. WE do not agree with the premise of the question – we do not consider that the proposed revision to planning policy/ guidance is resolved. We also are concerned about cumulative impacts. Whilst the proposed threshold appears reasonable, given the gravity of the flooding problem identified in the Pitt Review, it would seem essential to have standing requirements for smaller developments - or the thresholds should be lower. Small developments, if not correctly carried out, could individually and cumulatively contribute to the flooding problem. Such minor developments are unlikely to consider flood risk in as much detail, with technical expertise, as larger sites. There seems to be an assumption that soakaways will be used regardless of whether infiltration will provide an effective means of drainage. Smaller sites have little opportunity or resource to provide alternative sustainable options at discharge of condition stage if infiltration drainage is not an option. This will demand site-specific solutions and a degree of flexibility. This all perhaps points to whether this should be controlled through Building Regulations, a regime that already involves site inspections. Q8. What other maintenance options could be viable? Do you have examples of their use? Page 5 of 7 District Councils’ Network October 2014 In our view the key will be to have one body responsible for enforcing maintenance of SuDS. This should not be the local planning authority. This role could be performed by the LLFA or through Water and Sewerage companies, whereby the developers and the LLFA/ local company come to separate agreements outside the planning system. It is essential that the enforcement role is performed by appropriately qualified and experienced engineers used to such inspections and maintenance. A robust nationally applicable solution is therefore essential. Leaving it to individual owners and trusting that they will do it does not seem a realistic solution. Planning enforcement is not suited to the long term monitoring of how effectively flood assets are performing and SuDS systems. There is a parallel with adoption of highway infrastructure by Local Highway Authorities. An effective system would have these adopted by the relevant authority, maintained at public expense, with the cost recovered e.g. through the surface water drainage element of household water bills. Whatever solution is identified there must be clear arrangements around funding the responsibilities. Q9. What evidence do you have of expected maintenance costs? We have no detailed evidence of expected maintenance costs. In terms of costs, depending on the scheme, after adoption, for the first 3-4 years it may be that no crucial works are required, other than basic preventative maintenance. As materials and structures age and weather then the costs will increase. In particular paving and attenuation tanks under parking courts, for example, can become costly burdens. These costs are difficult to predict and depend on the development, but should be the subject of a submitted management plan for the lifetime of the development. We suggested that DEFRA/ DCLG undertake further investigation in this regard, to gain a more robust understanding of the lifetime costs. Maintenance options should be proposed and agreed as part of the technical assessment of the developer’s proposals. Q10. Do you expect the approach proposed to avoid increases in maintenance costs for households and developers? Would additional measures be justified to meet this aim or improve transparency of costs for households? SuDS should be seen as an integral part of delivering sustainable development and it therefore follows for their delivery and maintenance to become an integral part of development, in the same way as occurs with highway infrastructure. It would seem logical for the costs of SuDS delivery to fall with the developer and maintenance with households. Applying a flexible approach to the arrangements for implementing maintenance could help minimise costs to householders. However, the cost of implementing a sustainable drainage scheme (para 3.18) and maintaining it should not be a reason for not requiring one. The developer should take this into account when calculating development costs/ end sales values. The reason for implementing SUDs is to ensure that the flood risk to the site and other land and properties in the catchment is not increased. In terms of the flood risk to the wider community, all sites should Page 6 of 7 District Councils’ Network October 2014 implement SUDs schemes. Not to do so will increase the flood risk to existing properties and this is not equitable. As maintenance of SuDS is an expense not currently being paid, then whatever approach is adopted, this will inevitably result in increased maintenance costs. Would additional measures be justified to meet this aim or improve transparency of costs for households? Yes. Additional comment The questions do not ask about appropriate design standards for SuDS schemes. The design, construction and planning process would be simplified if Building Regulations requirements were of the same design standard as required by the NPPF. The NPPF requires a 1 in 100 year standard with an appropriate allowance for climate change - whereas Building Regulations general requirement is that surface water drainage should be “adequate” and it refers to a 1 in 10 year standard with no reference to climate change. Page 7 of 7 District Councils’ Network October 2014