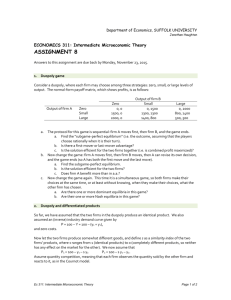

Comparative Political Economy Reader: Introduction This reader

advertisement

Comparative Political Economy Reader: Introduction This reader advocates for a market-institutional approach to studying political economy. This perspective contends that markets should be viewed as institutions embedded in a particular social and political context andmakes the study of these particular institutions its central mission. * Even classical liberals acknowledge that markets require states to set up and enforce the 'basic rules of the game': laws; infrastructure such as a monetary system; and basic public goods such as national defense. But we should stress that market systems are embedded in a far more extensive web of institutions * Mainstream economics assumes perfect markets (no transaction costs) for analytic leverage. But empirically speaking, these markets do not exist. The Four Disciplines New Institutional Economics (NIE) NIE scholars embrace the neoclassical assumption of utility maximization, yet they criticize standard economics for its failure to address economic institutions. NIE theorists build on the study of transaction costs first introduced by Ronald Coase. They define transaction costs as anything that impedes the costless matching of buyers and sellers. They divide transaction costs into two kinds: information costs and enforcement costs. Systems of property rights are seen as solutions to transaction cost problems. Criticisms: Some NIE theorists adhere too rigidly to the assumption of human rationality or adopt an overly functionalist view of institutional change by assuming that changes proceed toward more rational forms. The logic of NIE proceeds backward in the sense that it moves from perfect markets to institutions: transaction costs impede perfect markets; institutions solve this problem. Yet real-life history has proceeded in the opposite direction: Social institutions came first, and the market system evolved upon their foundation. See: Coase 1937: first introduced transaction cost economics in an article in which he asked: “Why do we have firms”? He argued that businesses create firms (corporate organizations) to reduce transaction costs. That is, businesses choose to perform certain services and to produce certain parts for themselves rather than purchase them on the open market. They do so because transaction costs are high in the marketplace, so it is more efficient to keep these functions out of the market and to conduct them in-house. He used this logic to theorize about where the firm would end and where the market would begin: the firm would expand to the point where returns disappear (i.e. where the benefits of further expansion do not exceed the costs). Douglas North (1977, 1981, 1989): Uses transaction costs to analyze the historical evolution of economic institutions. Throughout much of history, he argues, transaction costs were sufficiently high to prevent most transactions from taking place. As property rights developed, however, transaction costs declined and market systems became more efficient. North stresses that well-defined property rights spur innovation. He takes a ‘functionalist’ line in his early work arguing that people develop better institutional solutions over time (North 1981). In later work, however, he depicts institution change as a more open-ended process in which politics and ideology weigh heavily and changes may or may not constitute improvements (North 1989). In North’s critique of Polanyi, North agrees that price-making markets do not dominate resource allocation in history and do not even dominate today, noting the role of households, voluntary organizations, and governments. He then critiques Polanyi, however, by suggesting that what Polanyi calls “reciprocity” and “redistribution” are really just leastcost trading and allocation arrangements for an environment of high transaction costs. Williamson 1985: Williamson revisits Coase’s original question about the boundary between firms (“hierarchy”) and the market and in how firms make decisions about whether to produce inhouse or to buy parts on the market. One of Williamson’s key concepts is that of “asset specificity”. This gauges the degree of transferability of an asset intended for a specific use and a specific partner to other uses and partners. Assets with low specificity should be procured through the market. Highly specific assets on the other hand, have little value beyond their use in a particular transaction so companies are vulnerable to the threat of opportunism on the part of their suppliers. These should be vertically integrated. In Williamson’s more general view, economic institutions of capitalism have the main purpose and effect of reducing transaction costs, although he concedes that it is not their only purpose. In his analysis, the potential scope of transaction cost economics is huge, as the transaction is the basic unit of analysis in understanding capitalism. Economic Sociology Following Polanyi, economic sociologists believe that markets are governed by shared beliefs, customs, and norms, stressing that markets are embedded in social relations. They eschew he methodological individualism of standard economics, identifying collective actors – such as groups or even social systems – as important units of analysis. Some sociologists reject the assumption of utility maximization, arguing that people are as likely to follow logic of appropriateness in their actions as they are to adhere to a logic of utility. Economic sociologists emphasize that capitalism is a constructed and continually reconstructed system, rather than a natural system that can be articulated only through one set of rules. Economic liberalism and Marxism see only two possible political-economic outcomes for societies: capitalism or communism. Polanyi, in contrast, suggests that a range of alternatives in political economy are possible, because markets can be embedded in a range of different ways. This perspective problematizes the social relationships surrounding economic activity, in contrast with the functionalist approach of NIE, which assumes that institutional and social relationships exist to reduce transaction costs. Polanyi: Market systems do not spontaneously arise; on the contrary, governments have to actively create markets. “While laissez-faire economy was the product of deliberate state action, subsequent restrictions on laissez-faire started in a spontaneous way. Laissez-faire was planned; planning was not”. Polanyi stresses that markets undermind the existing social fabric because they turn labor, land, and money – which are part of society – into commodities. Society inevitably fights back against the market with regulation. This interaction is referred to as a ‘double movement’: the trading classes promote economic liberalism to foster a selfregulating market, but the working and landed classes push for social protection aimed at conserving man and nature. Fligstein: Lays out a “theory of fields” approach to market economies. “Fields” refers to arenas of activity that have an identity as a coherent issue-area or locus of activity, with social structures that go along with them. A distinctive feature of this analysis is that sectoral markets have social structures, which in turn affect market behavior in predictable ways. One of the core insights that emerge from Fligsein’s perspective of markets as fields is that firms try to produce a stable environment for themselves, so the ultimate motive of firms in this conception of markets is not always profit but also stability or survival. Another key insight is that market activity plays out a series of power struggles both within and among firms, where dominant actors, such as large incumbent firms, produce rules and meanings that allow them to maintain their advance. A market, in this view, is a socio-organizational construct intended to establish stability in exchange relations, and firms generate that stability by creating social structure in the form of status hierarchies. In other words, within a market there are dominant firms, incumbents, and challengers, and dominant firms create the social relations of the market to ensure their continued advantage. Rather than viewing institutions as the functional outcomes of an efficient process as does the NIE, Fligsteign argues that market institutions are cultural and historical products, specific to each industry in a given society, that have evolved through a continuous, contested process. These institutions have intersubjective meanings, that is, they depend intricately on how social actors perceive them and are not constructs that are separable from their embeddedness in society. Following Polanyi, Fligstein emphasizes that the state plays a crucial role in creating markets as institutions. The entry of a country into capitalism pushes states to develop rules that market actors cannot create themselves. States are also the focal points for economic and social actors during crisis and so are central in enforcing market institutions and sustaining markets through change. The manner and extent to which they do so depends on what type of state they are (interventionist versus regulatory) and their capacity. In a comparative sense, the configuration of rules and institutions within markets and the nature of social relationships between economic actors accounts for persistent differences in national political-economic systems. Kinds of “rules”: There are four types of rules relevant to producing social structures in markets: property rights, governance structures, rules of exchange, and conceptions of control. 1. Property rights: rules that define who has claims on the profits of firms. The constitution of property rights is a continuous and contestable political process, not the outcome of an efficient process. Organized groups from business, labor, government agencies, and political parties try to affect the constitution of property rights. Division of property rights is at the core of market society. 2. Governance Structures: refer to the general rules that define relations of competition and cooperation and define how firms should be organized. They define the legal and illegal forms of controlling competition, and take two forms: (1) laws and (2) informal institutional practices. E.g. Anti-trust laws, tariffs, professional associations, how to write contracts, where to draw boundaries of the firm. 3. Rules of exchange: Define who can transact with whom and the conditions under which transactions are carries out. Include rules regarding weights, common standards, shipping, billing, insurance, exchange of money (i.e. banks) and enforcement of contracts. They regulate health and safety standards. 4. Conceptions of control: Reflect market-specific agreements between actors in firms on principles of internal organization (i.e. forms of hierarchy), tactics for competition or cooperation (i.e. strategies), and the hierarchy or status ordering of firms in a given market. A conception of control is form of “local knowledge” (Geertz 1983), historical and cultural products. The "Propositions" 2.1: The entry of countries into capitalism pushes states to develop rules about property rights, governance structures, rules of exchange, and conceptions of control in order to stabilize markets. 2.2: Initial formation of policy domains and the rules they create affecting property rights, governance structures, and rules of exchange shape the development of new markets because they produce cultural templates that determine how to organize in a given society. The initial configuration of institutions and the balance of power between government officials, capitalists, and workers at that moment account for the persistence of, and differences between, national capitalisms. 2.3: State actors are constantly attending to one market crisis or another. This is so because markets are always being organized or destabilized, and firms and workers are lobbying for state intervention. 2.4: Policy domains contain governmental organizations and representations of firms, workers, and other organized groups. They are structured in two ways: (1) around the state’scapcity to intervene, regulate, and mediate, and (2) around the relative power of societal groups to dictate the terms of intervention. Political Science Do not represent a coherent research paradigm like NIE or economic sociology. They are divided between those who use the analytic tools of economics to study politics and those who focus on substantive areas that bridge economics and politics. See: Chalmers Johnson 19871: Focuses on the role of the state and its relationship to the economy. Argues that the Japanese state enjoyed relative autonomy from the demands of particular social groups plus a competent and powerful bureaucracy, and this enabled the government to formulate and implement pro-growth economic policies designed to shift the industrial structure towards high-value-added sectors. He extends this argument to other East Asian developmental states, such as South Korea and Taiwan, while noting variations among these. Riddle: What accounts for the Japanese ‘miracle’ – spectacular rate of growth since WWII? Previous Literature/Conventional Explanations: 1. National-character explanation argues that the economic miracle occurred because the Japanese possess a unique, culturally derived capacity to cooperate with one another. 2. ‘No-miracle-occurred’ school argue that what did happen was not miraculous but a normal outgrowth of market forces, due primarily to the actors of private individuals and enterprises responding to the opportunities provided in quite free markets for commodities and labor; state’s role has been exaggerated. 3. Specific Japanese institutions gave Japan a special economic advantage because of what postwar employers habitually call their “three sacred treasures” – the “lifetime” employment system, the seniority wage system, and enterprise unionism. 4. Theory of “free-ride” argues that Japan is the beneficiary of its postwar alliance with the United States: a lack of defense expenditures, reader access to its major export market, and relatively cheap transfers of technology. “Political Institutions and Economic Performance: The Government-Business Relationship in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan,” in The Political Economy of the New Asian Industrialism, ed. Frederick Deyo (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1987), 136-64 1 Main Argument: Stresses the role of the developmental state in the economic miracle. “Plan rationality” is state-led but not ideological, and stands in contrast with market-rationality: 1. concerned with “effectiveness” over “efficiency”. 2. Greater difficulty than the market system in identifying and shifting its sights to respond to effects external to the national goal (e.g. pollution) 3. But when the plan-rational system finally does shift its goal, it will commonly be more effective than the market-rational system. 4. Depends on the existence of a widely agreed upon set of overarching goals for society, such as high-speed growth. 5. Strength in dealing with routine problems, whereas the market-rational system is effective in dealing with critical problems. 6. Change will be marked by internal bureaucratic disputes, factional infighting, and conflict among ministries; in market-rational system, change will be marked by strenuous parliamentary contests over new legislation and by election battles. O’Donnell 1979: “Bureaucratic authoritarian” regimes in Latin America were relatively insulated from short-term political pressures and thereby able to enact long-term economic growth strategies. Katzenstein 19782: Developed a typology that combines a spectrum from organized to less organized societies with one from strong to weak states. Zysman 19833: Explicitly links the state, microlevel market institutions, and policy profiles. He focuses on financial systems, demonstrating a connection between strong states, credit-based financial systems, and industrial policies in France and Japan, on one hand, and weak states, equity-based financial systems, and more market-based adjustment strategies in Britain and the United States, on the other. Peter Evans: Links state strength not so much to autonomy from society but rather to the state’s penetration of (or collaboration with) society. Hall and Soskice: Varieties of Capitalism. Objective: Elaborate a new framework for understanding the variation in the political economies of developed countries. They trace their intellectual history lineage to three major approaches to comparative capitalism that fall within the rubric of political economy: Between Power and Plenty: Foreign Economic Policies of Advanced Industrial States (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press 1978, especially pp. 323-24). 3 Governments, Markets and Growth: Financial Systems and the Politics of Industrial Change (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983) 2 1. a perspective oriented around the strategic use of 'national champions' in core industrial sectors and state strength in leveraging key institutional structuressuch as economic plans and the financial systems. 2. neocorporatist analyses that focuses on the interaction of trade unions, employers and states, and 3. a series of broader viewpoints that engage sociology in studying 'social systems of production' such as collective institutions at the sectoral level, national systems of innovation, and flexible production regimes o the factory shop floor. The VOC approach argues that the role and capacity of government should not be overstated. In their view, firms are they key actors in a capitalist economy, whose activities aggregate into national economic performance. Although they take a national-level comparative perspective that recognizes that market-institutional structures are dependent on national regulatory regimes, they develop a comparative framework centered on firms and their relationships. They concentrate on four spheres of market institutions in which firms develop relationships to carry out economic activities: industrial relations between companies and employees, vocation training and education, corporate governance relations between firms and investors, and interfirm relations. In examining the importance of institutions in a market system, they emphasize the manner and extent to which those institutions condition strategic interaction among firms and other politicaleconomic actors. They build on the NIE tradition which emphasizes the development of contractual relationships to overcome transaction costs in economic collaboration. They also recognize the political factors at play and build on the economic sociology approach by reconizing that the firm is embedded in a web of interdpendent social relationship and shared cultural meanings. Centerpiece of the VOC framework is the dichotomous representation of liberal market economics (LMEs) and coordinated market economic (CMEs) and the comparison in their characteristics in terms of both relationships and outcomes. In broad strokes, the differences between these two types of capitalist economies are explained in terms of how firms coordinate their relationships and production activities through different sets of solutions. In LMEs—such as the US and Great Britain—firms primarily coordinate internally through hierarchical arrangements and externally through competitive market relationships. In CMEs—such as Germany and Japan—firms are more reliant on nonmarket relationships such as relational contracting and collaborative networking. Even though LMEs function through the price signals and formal contracts emphasized by neoclassical economics and NIE and CMEs seem to be more embedded in social relations in the manner emphasized by economic sociology, both systems are embedded in different ways of society and politics. One of the major utilities of the VOC approach is that it prevents us from falling into the analytical trap of assuming that one type of system is the default and the other the deviation to be explained. Systematic variation in corporate practice between LMEs and CMEs is generated by their different market-institutional makeup. Moreover, ‘institutional complementarities’ buttress these firm-centered relationships and the differences between LMEs and CMEs. This concept suggests that if political economies have developed one type of interaction (pricebased versus relational) in one sphere of economic practice they tend to develop—through the actions of all actors, including the state—complementary practices in other spheres, reinforcing the type of system and its outcomes. A related concept is that of “comparative institutional advantage,” the notion that different types of market-institutional systems structure different advantages for the firms functioning within them. Firms will be able to perform some types of economic activities more effectively because of the types of market institutions they are embedded within. This has implications for predictions regarding Globalizaiton. They anticipate one dynamic response to globalization in LMEs – where firms will pressure governments for more deregulation to enhance their flexibility in coordinating through markets – and another in CMEs—where firms and governments should be more resistant to deregulatory pressures because they challengetheir comparative institutional advantage. VOC framework predicts a bifurcated response to globalization—widespread deregulation in LMEs and limited change in CMEs—and they marshal evidence to claim that this does in fact represent the reality. History: Economic historians have stressed several core themes that have been overlooked by mainstream economists: entrepreneurship, innovation, personal leadership, and the evolution of economic institutions. See: Hobsbawm: Stresses the growth of domestic markets, enabled by improvements in tarsnportation, and the availability of expert markets, fueled by the expansion of the British Empire, in an account of the British Industrial Revolution. Hobsbawm challenges classical economists by problematizing technological innovation. He contends that business people seek profits, not innovation, and in practice they often favor profits at the expense of innovation. They will view industrial investments as profitable only if the potential market is large and the risks is manageable. The growth in domestic and export markets in the 18th century England provided just these conditions, and this fostered the Industrial Revolution. Gerschenkron: His argument on the timing of industrialization has been influential in political economy across disciplines. He argues that late-industrializing countries face fundamentally different challenges from Britain, the first country to industrialize. His approach contrasts to Walter Rostow’s more linear, uniform model of stages of growth. Gerschenkron stresses that late-industrializing countries confront a huge technological gap, so they do not have the luxury of industrializing slowly. They must make massive investments to shift rapidly into heavy industry. This requires large-scale financing, an institutional mechanism for channeling the funds, and a powerful ideology to motivate the mobilization efforts. Industrial banks provided the institutional mechanism in Germany, whereas the state played this role in Russia. Late industrializing would require a more powerful state because of the larger technological gap, and this might well take the form of a totalitarian state, as in the Soviet Case. Landes Landes argues that contemporary international empirical evidence is against neoclassical economic theory and its belief that all nations will eventually industrialize and converge. He thus disagrees with Rostow’s unilinear perspective. Landes agrees with Gerschenkron that the government can have a very important role to play (both empirically and normatively) in late development and points to historical evidence of the necessity of state intervention in development. In addition, he emphasizes culture as a factor in the pursuit of national wealth but admits that culture is unsatisfying as a monocausal answer. In short, culture and economics interact in the history of development. Vogel: Vogel articulates the market-institutional counterpoint to the liberal perspective on relationship between states and markets. He argues that “marketizing” reforms in advanced industrial countries should be seen as a positive, creative process that entails the development and transformation of market institutions rather than perceived as a negative process of stripping away government regulation. Vogel builds on Polanyi’s work in tackling the notion that markets are free or perfect and hence challenges the prevailing liberal discourse on the relationship between markets and governments. The central element of Vogel’s argument is a step away from the conventional regultation-competition dichotomy that dominates more debates about markets of reforms. He points out that liberalization of markets to increase competition actually requires reregulation rather than deregulation: freer markets need more rules. Indeed, some of the boldest deregulation programs, including those of Thatcher era, have been accompanied by a proliferaiton of rules and regulatory agencies. 1. There are no “free” markets 2. There is no such thing as a disembedded or even a less embedded market system 3. Market reform involves changes at every level of a political-economy system: government policies, private sector practices, and social norms 4. The regulation-versus-competition dichotomy that animates most debates about market reform is fundamentally misleading 5. Government-versus-market dichotomy that animates more debates about economic policy is also misleading. 6. Market reform is a primarily create process not a destructive one. Kinds of re-regulation: pro-competitive, juridical, strategic, and expansionary. 1. Market reform is a highly complex process precisely because it requires building new institutions and not simply removing barriers 2. Market reform often requires not just one policy change but a wide range of interrelated steps 3. Market reform is not simply a process of policy change but a combination of policy change and societal response 4. There is no single equilibrium for optimal market reform 5. Market reform is inherently a political process.