Kant and the Categorical Imperative Kant believes that morality is

advertisement

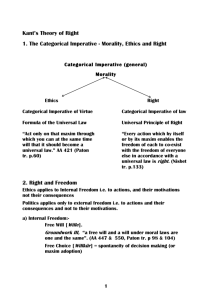

Kant and the Categorical Imperative Kant believes that morality is experienced as a command or ‘imperative’. In other words it tells us what we ‘ought’ to do. An imperative is in inner ‘tug’ on our will, a compulsion to act in one way rather than another. But there are two different types of imperative – 2 distinct senses of the term ‘ought’. Hypothetical imperatives – One kind of ‘ought’ is a conditional, or in Kant’s terminology, a hypothetical imperative. If you want X then you ought to do Y. This kind of ‘ought’ depends upon your having a certain goal or desire. The first part of the statement gives us the condition; the second part tells us what to do to meet this condition. In other words, the ought is dependent or conditional upon the existence of a certain desire. All such hypothetical/conditional imperatives will involve an ‘if’ at the beginning as not everyone will want to follow the same imperative. For example, if you want a good grade in your exams you ought to work hard. Many of the imperatives we encounter in life are based on this type of self-interested reasoning – first of all we identify things that we think are in our self-interest (e.g. getting good grades so we can go to uni), then we figure out what we must do in order to get this thing (listen in class, work hard and revise). Categorical Imperatives – However, Kant isn’t interested in this kind of hypothetical imperative. The imperatives that Kant thinks are central to morality are ones that are not dependent on any set of conditions. These types of ‘oughts’ are unconditional, or categorical imperatives. An example might be that you ‘ought to respect your mother and father’. This use of ought is not dependent on any goals or aims you may have – the ‘if you want X’ part of the imperative has disappeared leaving only ‘you ought to do Y’. These sorts of imperatives tell us that we have a certain obligation or duty regardless of the circumstances. It is this sort of ought which Kant regards as the genuinely moral ought. THE Categorical Imperative – Kant’s ethical theory is known as the Categorical Imperative. There are three principles of this theory: 1. The Universal Law: ““There is only one categorical imperative. It is: Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law”. The categorical imperative is ‘Do not act on any principle that cannot be universalised. In other words, moral laws must be applied in all situations and to all rational beings universally, without exception. If an action is right for me, it’s right for everyone. If it’s wrong for one person, then it’s wrong for all people. Kant is basically asking us to think of an act we must then imagine a world where everyone also carried out the same act. We must then consider if this would make the world a good place. If it does not then it is a wrong act. For example stealing, if we think about a world where it was ok for everyone to steal we can see that stealing is a bad thing. So our duty must be not to steal. “For an action to be morally valid, the agent – or person performing the act – must not carry out the action unless he or she believes that, in the same situation, all people should act in the same way”. The moral law permits certain actions and forbids others. Kant argued that to allow exceptions would harm someone and have an eroding effect on society. He gave an example using the case of lying. In certain circumstances we might think a lie is better than the truth. It might get us out of trouble! Kant argued that a lie always harms someone – if not the liar then mankind generally, because it violates the source of law. If everyone was to act in this way, society would become intolerable. 2. Treat Humans as Ends in Themselves: Kant’s second principle of the categorical imperative is: “So act that you treat humanity, both in your own person and in the person of every other human being, never merely as a means, but always at the same time as an end”. What this means is that you can never treat people as means to an end. You can never use human beings for another purpose, to exploit or enslave them. Humans are rational and the highest point of creation, and so demand unique treatment. This guarantees that individuals are afforded the same moral protection. There can be no use of an individual for the sake of the many – as is the case with utilitarians, who can sacrifice the few for the greater good of the greater number. Kant argued that we have a duty to develop our own perfection, developing our moral, intellectual and physical capabilities. We also have a duty to seek the happiness of others, as long as that is within the law and allows the freedom of others. So we should not promote one person’s happiness if that happiness prevents another’s happiness. 3. Act as If You Live in a Kingdom of Ends: The third principle of Kant’s categorical imperative is: “so act as if you were through your maxim a law-making member of a kingdom of ends”. Kant required moral statements to be such that you act as if you, and everyone else, were treating each other as ends. You cannot create a maxim such as ‘I may lie as all others lie’. If such rules were pursued, society would become intolerable. Maxim = a general principle of action