1 - Durham e-Theses

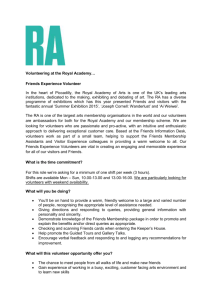

advertisement