Nordiko Addendum - Safe Work Australia Public Submissions

advertisement

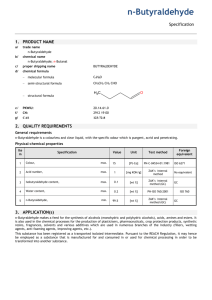

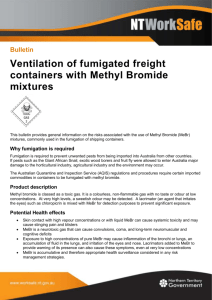

NGMW003 - Nordiko Addendum to Submission by Nordiko Quarantine Systems Pty Ltd Review of National Guidance Material for Working Safely on the Waterfront What is the nature and scope of the problem? There are two parts to the problem, as defined presently in the section: Contaminated or oxygen deficient atmospheres (p16-17, Working Safely with Containers): 1. 2. Entry into ships holds and other confined spaces on board vessels: Oxygen deficient atmosphere detection and VOC gas detection equipment is readily available in one hand-held monitor and can provide a quick reading for such confined spaces on vessels. Handling, transport and entry into shipping containers: Unsafe atmospheres inside shipping containers arise from a variety of causes, but similar detection equipment, with an appropriate probe pushed through the door seal, can rapidly check air quality. Comments below apply to the risk as it relates to shipping containers: International studies have consistently shown that between 10% and 20% approximately of shipping containers have unsafe atmospheres.1 This can arise from fumigation (eg methyl bromide, phosphine, sulfuryl fluoride etc) or gases emitted by cargoes (eg formaldehyde from furniture, benzene from machinery, toluene from shoes etc). Prevalence of formaldehyde for instance, is significantly increasing in container loads. How many containers actually have contaminated atmospheres? A study conducted by the Australian Customs Service in 2008 of more than 14,000 inbound containers, revealed that 17% had unsafe gas levels2. The Australian Government has a strict protocol requiring container atmospheres to be tested for its employees (eg Customs), and if necessary ventilated, prior to entry by any personnel3. Large importing companies are also adopting this procedure, which has standardised in comparable countries since the last local guidance was released in 2009. What does this mean in terms of total container numbers in Australia? Today Australia imports about 2 million containers a year, applying the 17% unsafe rate to this means that there are more than 300,000 containers at risk , and this number will increase significantly in coming years. By 2025, due to forecast trade growth4, this could increase to more than 700,000 at risk containers, each year. How can this affect workers who are exposed to these risks? Health affects have been documented for exposure to the types of gases that are found in shipping containers. These gases include neurotoxins, cardiovascular and pulmonary toxins and those that cause tissue dysfunction and destruction5. Effects can be acute and immediate, affecting respiration and producing nausea, sometimes requiring hospitalisation6. Alternatively, for workers who regularly enter shipping containers that are not tested or ventilated, there is an unassessed risk of sub-symptomatic repeated exposure to toxins that can be cumulative eg formaldehyde/benzene as carcinogens. Nordiko is aware of Australian incidents of these effects, research in New Zealand is investigating linkages7. Safe Work Australia has very recently reclassified formaldehyde from a Class 3 to a Class 2 Carcinogen: “may cause cancer by inhalation”8. These effects extend beyond stevedoring workers to include compliance personnel (Customs, AQIS), supervisors, forklift, truck and freight train drivers, and warehouse, distribution and retail employees. What are the present controls? Fumigated containers are supposed to have warning labels attached, but these are often missing. Containers with cargoes that may desorb gases in transit contain no warnings. WorkSafe Victoria has guidance notes for industry recommending forced ventilation, or an extended period of natural ventilation 9. Many other states anticipate a national approach. Safe Work Australia is conducting a study into residual chemicals in shipping containers. Most of Australian industry, with a few exceptions, is ignorant of the problem. What will be the impact on container turnaround efficiency of addressing this safety issue? Once it is recognised that it is unsafe to just open and enter an import container on arrival, without performing a risk assessment of the hazard of residual gas, experience has shown that passive (open door) ventilation can take up to 48 hours, without guarantee of success. Commercial experience with forced ventilation systems show effective results in under an hour10. So efficiency can be improved by applying relevant technology. Overseas experience at container ports many times busier than Australia’s suggests that this is not a productivity issue, when properly managed. References: 1 Baur Germany 37%, RIVM Netherlands 20%, NZ Customs 18% - references available on request 2 C. Frost, Safety in Sea Container Examination The Australian Experience, presentation at the WCO Technology and innovation Forum November 2010 3 Australian Customs OHS Instruction and Guidelines Fumigants July 2007[1] Booz & Company, Intermodal Supply Chain Study 2009 for National Transport Commission by Shipping Australia 5 Refer to MSDS’s for various gases: Methyl Bromide, Phosphine, Sulfuryl Fluoride, Formaldehyde, Benzene, Toluene etc. Available from Nordiko on request. 6 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, July 15 2011, Vol. 60 No. 27: Illness Associated with Exposure to Methyl Bromide – Fumigated Produce – California, 2010 7 Professor Ian Shaw – Canterbury University, Christchurch New Zealand: Potential Linkage Method between Exposure to Methyl Bromide and Motor Neurone Disease 8 Safe Work Australia website: Hazardous Substances Information System (HSIS) July 2012 9 WorkSafe Victoria – Health and Safety Solutions: Fumigated Shipping Containers - Venting Prior to Unpacking (by end user) HSS0116/01/10.09 10 Empirical data available from Nordiko on request 4