HEAT-PPCI ACCP Cardiology PRN e-Journal Club Article Review

advertisement

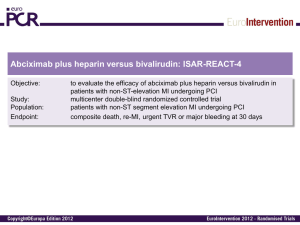

HEAT-PPCI ACCP Cardiology PRN e-Journal Club Article Review Kathleen Faulkenberg Trail Review: Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the preferred reperfusion method in the setting of an S-T segment myocardial infarction (STEMI). Many trials have compared heparin, in combination with a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (GPI), to bivalirudin with bivalirudin demonstrating a better safety profile with regard to less major bleeding events. However, the bleeding advantage related to bivalirudin in these trials may have been due to differential use of GPIs and not the choice of anticoagulant used during PCI. The HEAT-PPCI trial investigators sought to determine an optimal anti-platelet/anti-thrombic regimen by comparing the use of heparin and bivalirudin in PCI. The HEAT PPCI trail was a single center, open label, randomized control trial which took place from February 7, 2012 to November 2013. Patients were enrolled with a suspected STEMI who were older than 18 years of age. A delayed consent process was used in the setting of emergency angiography to increase the number of potential eligible study participants and to have the trial population more accurately reflect clinical practice. A total of 914 patients were randomized to receive heparin bolus of 70units/kg (targeting activated clotting time >200s) just prior to the procedure or bivalirudin 0.75mg/kg followed by an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/hr for the duration of the procedure (targeting activated clotting times of >225 seconds). Abciximab was allowed as bailout therapy for both groups with rates of 13% in the heparin arm and 15% in the bivalirudin arm. Glycoprotein IIb/IIa inhibitor (GPI) use was permitted in the setting of a large thrombus, slow or no reflow or a thrombotic complication according to ASC guidelines. Efficacy and safety outcome were evaluated as primary outcomes. The efficacy outcome included at least one or more major adverse cardiac events (MACE) at 28 days and the safety outcome evaluated major bleeding at 28 days. Bleeding was defined by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria. Secondary outcomes included stent thrombosis rates, cardiac enzyme release and minor bleeding events. A pre-defined subgroup analysis included route or arterial access, left ventricular function, age, history of diabetes, type of P2Y12 inhibitor used and PCI attempted. The primary efficacy outcome was statistically significantly different, occurring in 8.7% in the bivalirudin group and 5.7% in the heparin group (RR=1.52, 95% CI 1.09-2.13, p=0.01) favoring the use of heparin. This outcome was primarily driven through reducing the risk of developing a new myocardial infarction or re-infarction and additional unplanned target lesion revascularization in the heparin group. There was no difference in the rates of major or minor bleeding when comparing heparin to bivalirudin, which is a stark contrast to previous results from other trials. Acute stent thrombosis rate was significant for the secondary outcomes occurring in 3.4% of the bilvairudin arm and 0.9% in the heparin arm (RR=3.91, 95% CI=1.61-9.52, p=0.001), which was defined as occurring within < 24hours and is also reflected in results from other contemporary trials comparing heparin and bivalirudin. Bivalirudin Group N=905 79/905 (8.7%) 24/905 (2.7%) 24/905 (2.7%) Heparin Group N=907 52/907 (5.7%) 8/907 (0.9%) 6/907 (0.7%) MACE Reinfarction Unplanned target lesion revascularization Stent Thrombosis 24/697 (3.4%) 6/682 (0.9%) rate Major Bleeding 32/905 (3.5%) 28/907 (3.1%) Minor Bleeding 83/905 (9.2%) 98/907 (10.8%) Any Bleeding 113/905 (12.5%) 122/907 (13.5%) Event Table 1. HEAT-PPCI trail primary outcomes at 28-days [1]. RR (95% CI) p Value 1.52 (1.09-2.13) 3.01 (1.36-6.66) 4.01 (1.65-9.76) 0.01 0.004 0.001 3.91 (1.61-9.52) 0.001 1.15 (0.7-1.89) 0.85 (0.64-1.12) 0.93 (0.73-1.18) 0.59 0.25 0.54 In comparison to three contemporary trials evaluating the use of heparin vs. bivalirudin in the setting of STEMI, HEAT-PPCI favored heparin over bivalirudin primarily due to the decreased rate of acute stent thrombosis and similar bleeding risk between both groups. However, some consideration should be given to the route of arterial access and type of P2Y12 inhibitor used. HEAT-PPCI used radial access 80% of the time, which likely attributed to the decreased bleeding event rate in comparison to the femoral approach, especially if the interventional cardiologists are highly skilled in this technique. Additionally, the vast majority of patients received aspirin and ticagrelor loading doses prior to PCI which also may have influence their primary efficacy outcome in comparison to trials that used less potent regimens, such as 300mg or 600mg of clopidogrel. Follow up Q&A: 1. What are some of the ethical issues related to the delayed consent design of the trial? The ethical dilemma presented with using a delayed consent process is founded in the lack of patient consent prior to randomization. However it should be noted that all patients were provided consent post-procedurally. Delayed consent process enrolled patients into the trial prior to obtaining consent or discussing details of the consent with family members prior to PCI in the setting of emergency angiography. This effectively prevents the delay of urgent cardiac treatment in patients who may be incompetent. Additionally, both heparin and bivalirudin are ACC/AHA Class Ia recommendations to be used procedurally in the setting of a STEMI. This is considered ethical for the purposes of this study as the decision to choose either heparin or bivalirudin would be left to the physician’s discretion without consulting the patient on their preferences. 2. Which is more potent anticoagulant? Any pharmacokinetic advantages to either therapy? Why do you think there was signal to increase thrombotic events (including stent thrombosis)? Heparin is an indirect thrombin inhibitor on bound clots while bivalirudin is a direct thrombin inhibitor for both circulating and bound clots. Bivalirudin also exerts anti-platelet effects through inhibition of thrombin mediated platelet aggregation. For these reasons, bivalirudin theoretically is the more potent agent for anticoagulation. Heparin is highly protein bound with unpredictable pharmacokinetic parameters. Furthermore, there has been criticisms over whether patients enrolled in the bivalirudin arm were under-dosed based on ACT values. HEAT-PPCI investigators report 13% of patients in the bivalirudin arm required re-bolusing to achieve targeted ACTs. In comparison to EUROMAX and HORIZONS-AMI, only 02% of patients required bivalirudin re-bolusing. If target ACTs were continually sub-therapeutic requiring re-boluses, then this may account for the increased rate of stent thrombosis in the bivalirudin group. 3. Regarding issues with bivalirudin and efficacy, ACUITY showed a signal (of stent thrombosis). Was there any data shared regarding the timing of P2Y12 and its impact of outcomes? Perhaps the signal from ACUITY indicated a problem with bivalirudin versus timing and selection of antiplatelet. Timing of the P2Y12 inhibitor in ACUITY was left to the provider, however it was recommended that patients receive it no later then 2 hours after PCI[2]. Approximately 36-38% of each treatment arm received a P2Y12 inhibitor after PCI. Furthermore, a subgroup analysis revealed that patients who did not receive a P2Y12 before PCI had more frequent ischemic events in the bivalirudin monotherapy group than with the combination of heparin with a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (GPI). There have been animal and human studies that analyze the synergistic effects of using a direct thrombin inhibitor with a P2Y12 inhibitor to antagonize the multiple different g-protein coupled pathways, which may play a key role as demonstrated in the subgroup analysis of ACUITY. Information about the exact timing of clopidogrel was not available for all patients enrolled in the ACUITY trial and study investigators did not preform platelet function testing to determine if one arm had a high proportion of clopidogrel “resistance”. While the subgroup analysis in ACUITY demonstrated borderline statistical significance (p=0.054) with regard to an increase in ischemic events in the bivalirudin group vs. the heparin combined with a GPI, it is recommended that the P2Y12 inhibitor be administered prior to PCI to optimize outcomes with bivalirudin. In comparison to HEAT-PPCI, >99% of patients received a loading dose of a P2Y12 inhibitor prior to PCI, however there is not information available with regard to timing of P2Y12 inhibitor that would suggest the outcomes demonstrated with bivalirudin. 4. Other than initial boluses, were patients treated with infusion of heparin and bivalirudin as well during PCI as in previous trial? Patients were given a 70unit/kg heparin bolus bolus prior to PCI and additional boluses were administered if activated clotting times were <200seconds 5-15minutes after bolus administration. Bivalirudin was administered as a 0.75mg/kg bolus followed by an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/hr for the duration of the procedure. Re-boluses of 0.3mg/kg were allowed 5-15 minutes after initial bolus or at the end of PCI if the activated clotting time was <225seconds. HORIZONS AMI used a 60unit/kg heparin bolus with subsequent boluses allotted to target clotting times of 200-250 seconds. Bivalirudin was administered as a 0.75mg/kg bolus with an infusion of 1.75mg/kg/hr for the duration of the procedure. However, it should be noted that both heparin and bivalirudin could be continued post-procedurally in HORIZONS AMI if the clinician decided it was clinically necessary[3]. EUROMAX used similar bolus dosing of bivalirudin as compared to HEAT-PPCI and HORIZONS-AMI with the exception that an hourly infusion of 0.25mg/kg/hr or higher be continued 4 hours post-procedurally. Patients in the heparin arm of EUROMAX received 100units/kg/hr with a GPI or 60units/kg with a GPI[4]. 5. Any sub-group analysis for the femoral approach? Subgroup analysis of the arterial access demonstrated the potential benefit of bivalirudin over heparin the composite primary outcome in patients undergoing PCI with the femoral approach (11.7% in the bivalirudin group vs. 9.9% in the heparin group, RR=1.18, 95% CI=0.63-2.19, p=0.48 for arterial access site) 6. Do you think the use of abcixamab would have impacted the results? Undeniably, the use of abcixamab would have likely impacted the bleeding outcomes of the trial, as the half-life is much longer than eptifibitide. However, since both treatment arms had similar rates of GPI use for bailout (15% in the bivalirudin group and 15% in the heparin group), an increase in bleeding rates would be similar in both groups. 7. Do you think the results would be able to be used in facilities using clopidogrel? Ticagrelor has benefits over the clopidogrel in the setting of treatment prior to PCI. Ticagrelor is a reversible, direct-acting oral P2Y12 which provides more rapid and consistent P1Y12 antagonism over clopidogrel, which is a pro-drug and may have variable platelet inhibition based on patient specific factors. The PLATO study investigators compared the clopidogrel (300mg oral load) to ticagrelor (180mg po load) in the setting of ACS for prevention of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular death[5]. This study demonstrated a statistically significant (P<0.001) benefit in the use of ticagrelor over clopidogrel for the reduction of the primary outcome. However, not all patients underwent PCI. While ticagrelor in the more potent anti-platelet, it has only slight benefit over clopidogrel in the prevention of recurrent MI and stent thrombosis, which was the driving difference in 28 day MACE rate favoring heparin over bivalirudin in PCI per the HEAT-PPCI trial. Furthermore, subgroup analysis data from HEAT-PPCI demonstrates that regardless of the type of P2Y12 inhibitor used, heparin was favored over bivalirudin for the composite primary outcome at 28 days. References: 1. 2. Shahzad, A., et al., Unfractionated heparin versus bivalirudin in primary percutaneous coronary intervention (HEAT-PPCI): an open-label, single centre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 2014. Stone, G.W., et al., Bivalirudin for patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med, 2006. 355(21): p. 2203-16. 3. 4. 5. Stone, G.W., et al., Bivalirudin during primary PCI in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med, 2008. 358(21): p. 2218-30. Steg, P.G., et al., Bivalirudin started during emergency transport for primary PCI. N Engl J Med, 2013. 369(23): p. 2207-17. Wallentin, L., et al., Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med, 2009. 361(11): p. 1045-57.