At Home with Modernism - American Institute of Architects

advertisement

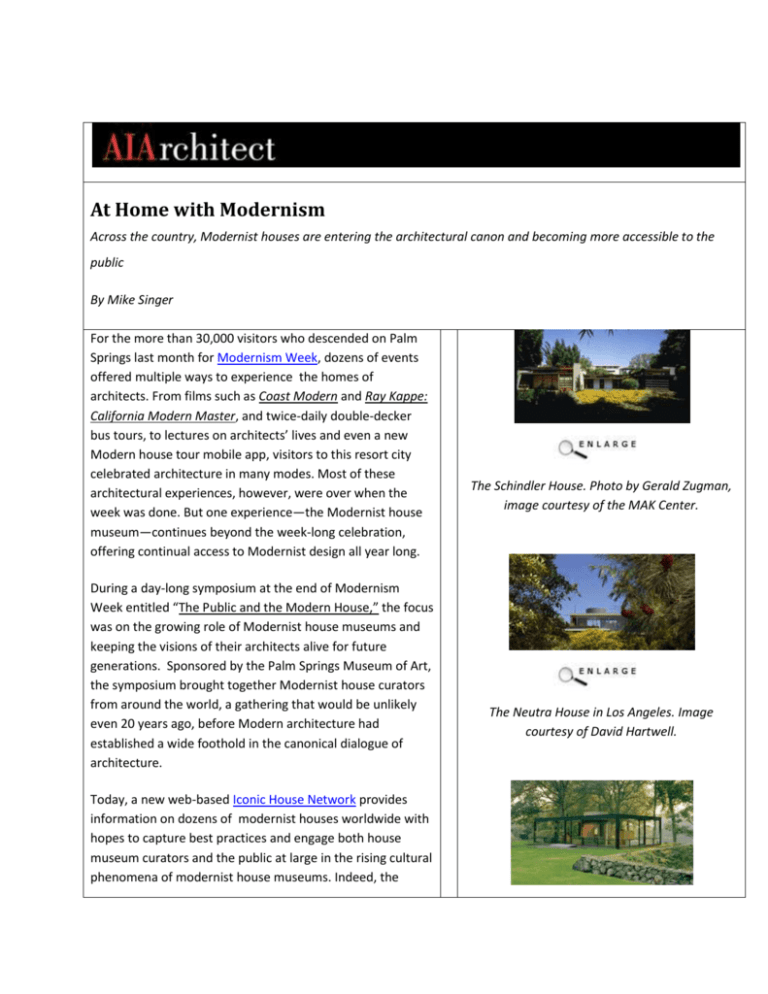

At Home with Modernism Across the country, Modernist houses are entering the architectural canon and becoming more accessible to the public By Mike Singer For the more than 30,000 visitors who descended on Palm Springs last month for Modernism Week, dozens of events offered multiple ways to experience the homes of architects. From films such as Coast Modern and Ray Kappe: California Modern Master, and twice-daily double-decker bus tours, to lectures on architects’ lives and even a new Modern house tour mobile app, visitors to this resort city celebrated architecture in many modes. Most of these architectural experiences, however, were over when the week was done. But one experience—the Modernist house museum—continues beyond the week-long celebration, offering continual access to Modernist design all year long. During a day-long symposium at the end of Modernism Week entitled “The Public and the Modern House,” the focus was on the growing role of Modernist house museums and keeping the visions of their architects alive for future generations. Sponsored by the Palm Springs Museum of Art, the symposium brought together Modernist house curators from around the world, a gathering that would be unlikely even 20 years ago, before Modern architecture had established a wide foothold in the canonical dialogue of architecture. Today, a new web-based Iconic House Network provides information on dozens of modernist houses worldwide with hopes to capture best practices and engage both house museum curators and the public at large in the rising cultural phenomena of modernist house museums. Indeed, the The Schindler House. Photo by Gerald Zugman, image courtesy of the MAK Center. The Neutra House in Los Angeles. Image courtesy of David Hartwell. number of modern house museums has increased dramatically ever since Edgar J. Kaufmann, jr., bequeathed Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy in 1963, making it the first Modernist house to enter the public domain. Today, Fallingwater is visited by 160,000 people annually. “You now have access to capture living memory, either from the house creators, or those who were close to them, allowing you to think about the process involved in modern living,” says Susan MacDonald, the head of field projects at the Getty Conservation Institute, which is working with the Eames Foundation to make the Los Angles house of Ray and Charles Eames, built in 1949, appear as it looked at the time of Ray’s death in 1988. As with the Eames and other houses now available for public tours, residences designed by architects as their own personal homes provide a unique viewpoint into their respective design philosophies. These houses are often laboratories for formal and aesthetic experiments that work their way into the mainstream. Here’s a look at what three Modernist house museums are doing to keep the visions of the architects, who designed and lived in these homes, alive for the public and posterity. Rudolph and Pauline Schindler House Designed as a live-work space for two couples with a shared kitchen and an apartment for guests, the 2,500 square foot Schindler House in Los Angeles was visited by leading intellects and social activists of the day, including Richard Neutra, who was a five-year live-in guest during the 1920s when he first came to California to work with Schindler. Schindler himself moved to Los Angeles in 1919 to oversee design of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Hollyhock House in East Hollywood. The house pinwheels outward, with wings that form protected and partially enclosed garden spaces accessible through sliding wood doors that help to bathe the interior in sunlight. Its mix of heavy concrete, wood frames, and light Philip Johnson’s Glass House. Photo by Eirik Johnson, courtesy of the Glass House. The Eames House. Photo by Eames Demetrios, courtesy of the Eames office. make the Schindler House a precursor to the more materially stringent Modernism to come, and recalls Schindler’s early tenure with Frank Lloyd Wright in Chicago. Decades after it was built in 1922, the house became the model for Arts and Architecture Magazine’s post-WWII Case Study Houses series, according to James Steele’s Schindler (Taschen). Symposium keynote speaker Kimberli Meyer, director of the MAK Center (which manages the Schindler House) says programming is key in preserving Modernist houses. “It is not only important to preserve these Schindler Modernist buildings, but it is important to enliven the space in ways that reflect how life was when the Schindlers were there,” she says. Today, the MAK Center is using the idea of a modernist house museum to engage a group of artists, architects, and writers in exploring systems designed to activate a person's experience of a particular locale. The current exhibition, Plan your visit, questions the nature of tourism in curated and controlled environments. Richard Neutra House In the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles, AIA Gold Medalist Richard Neutra’s design influence is on display at his VDL Research House. (VDL are the initials of Dutch industrialist Cornelius Van der Leeuw, who provided Neutra with a gift to build his family home). VDL Research House I, built in the International style in 1932 with ribbon windows and a concrete façade, served as both Neutra’s house and studio—and a place of experimentation. A 1963 fire destroyed the original Neutra house, leading to the construction of VDL Research House II in 1966 on the same footprint. It’s a work of late Modernism, with extensive use of mirrors, glass, and shiny surfaces that allow visitors to experience reflections of trees, flowers, and changing weather patterns. The original first-floor office and drafting rooms were opened up to become the Richard J. Neutra Institute seminar room and his wife Dione’s music recital room. In 1990, Dione Neutra died, and the house was bequeathed to Cal Poly Pomona, with the agreement that one of its faculty members would live in the house and manage it. “It’s an interesting arrangement,” says Sarah Lorenzen, chair of the Architecture Department at Cal Poly Ponoma, and current resident director of the VDL Research House. “In the last five years, we’ve been trying to reinvigorate the house with a series of events. We have concerts there, and art collaborations with galleries in Los Angeles. We hold student juries and student presentations there. Students also work as architectural tour guides for the house every Saturday. They not only talk about the house, but [about] their experience studying architecture and their connection to the house as a laboratory for architecture.” The Phillip Johnson Glass House Architectural trendsetter Philip Johnson, FAIA, may be noted for Postmodernist leanings with his 1984 Chippendaletopped AT&T building, but in the 1950s, a tiny pavilion of a house outside of New York came to define Modernist architecture’s ethos of orthogonal material honesty and lightness: the Glass House in New Canaan, Conn. In 2007, the Glass House was the first Modernist house property in the country to become a National Trust Historic Site; it now receives 12,000 visitors a year.. Henry Urbach, director of the Glass House, is keeping the legacy of Phillip Johnson, an AIA Gold Medalist, alive on his 47-acre estate. First conceived of as a weekend retreat in 1949 that Johnson shared with his partner David Whitney, the estate grew to include 14 buildings, including exhibition and gallery space. “My hope is to reanimate the Glass House as a curatorial laboratory to complement Johnson’s and Whitney’s work,” Urbach says. “Exhibitions and other programs will allow the public to experience the site in new ways so that the Glass House continues to exist as a site of cultural production, a place of innovation and discovery.” In addition to art exhibits such as a recent Frank Stella show, the public can interact with the Glass House in digital, multimedia forums. Glass House Conversations, an online public discussion space, continues the historic role of the Glass House as a gathering place for conversations on architecture, art, and design. The book Modern Views reflects on the idea of aglass house through architect dialogues with another National Trust modernist house museum, Mies Van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House. Recent Related: Edwards Harris Center to Provide Year-Round Showcase for Palm Springs Architecture Architecture as Economic Development in a Modernist Mecca Mid-Century Modernist Sunnylands Estate Opens to the Public Paul Revere Williams: The AIA’s First African-American Member was an Architect to the Stars Back to AIArchitect March 8, 2013 Go to the current issue of AIArchitect