COAG Decision Regulation Impact Statement

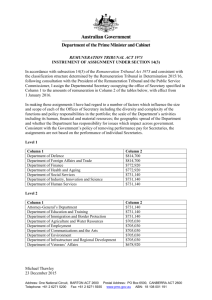

advertisement