Website Word Version

advertisement

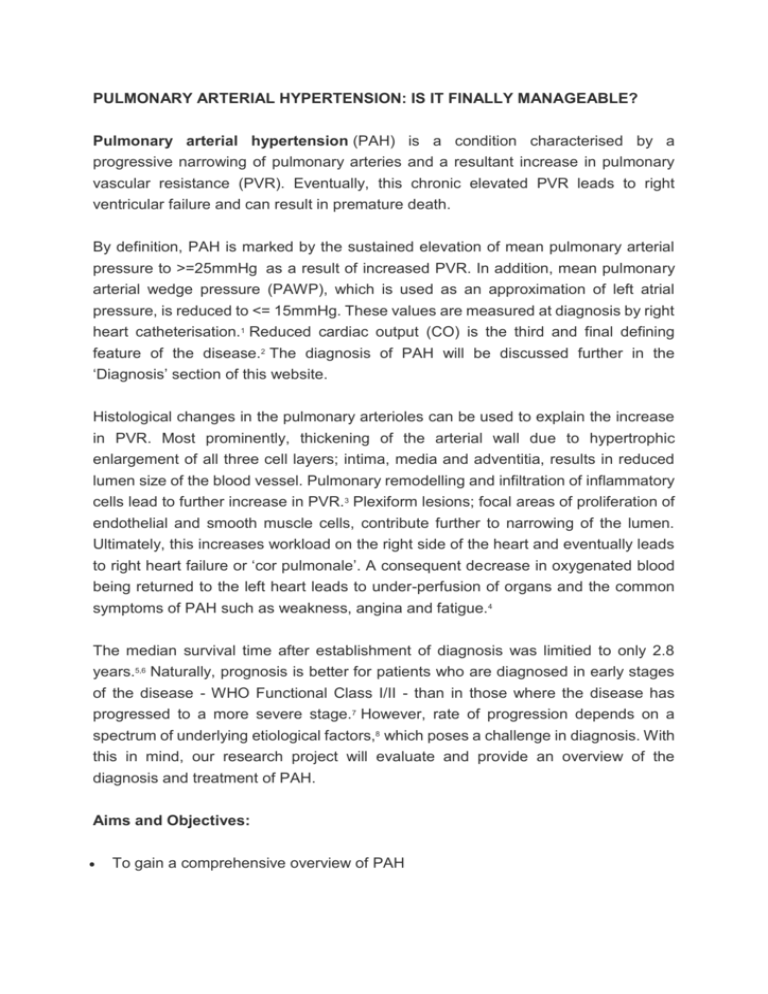

PULMONARY ARTERIAL HYPERTENSION: IS IT FINALLY MANAGEABLE? Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a condition characterised by a progressive narrowing of pulmonary arteries and a resultant increase in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR). Eventually, this chronic elevated PVR leads to right ventricular failure and can result in premature death. By definition, PAH is marked by the sustained elevation of mean pulmonary arterial pressure to >=25mmHg as a result of increased PVR. In addition, mean pulmonary arterial wedge pressure (PAWP), which is used as an approximation of left atrial pressure, is reduced to <= 15mmHg. These values are measured at diagnosis by right heart catheterisation.1 Reduced cardiac output (CO) is the third and final defining feature of the disease.2 The diagnosis of PAH will be discussed further in the ‘Diagnosis’ section of this website. Histological changes in the pulmonary arterioles can be used to explain the increase in PVR. Most prominently, thickening of the arterial wall due to hypertrophic enlargement of all three cell layers; intima, media and adventitia, results in reduced lumen size of the blood vessel. Pulmonary remodelling and infiltration of inflammatory cells lead to further increase in PVR.3 Plexiform lesions; focal areas of proliferation of endothelial and smooth muscle cells, contribute further to narrowing of the lumen. Ultimately, this increases workload on the right side of the heart and eventually leads to right heart failure or ‘cor pulmonale’. A consequent decrease in oxygenated blood being returned to the left heart leads to under-perfusion of organs and the common symptoms of PAH such as weakness, angina and fatigue.4 The median survival time after establishment of diagnosis was limitied to only 2.8 years.5,6 Naturally, prognosis is better for patients who are diagnosed in early stages of the disease - WHO Functional Class I/II - than in those where the disease has progressed to a more severe stage.7 However, rate of progression depends on a spectrum of underlying etiological factors,8 which poses a challenge in diagnosis. With this in mind, our research project will evaluate and provide an overview of the diagnosis and treatment of PAH. Aims and Objectives: To gain a comprehensive overview of PAH To explore the different diagnostic modalities and making comparisons between them To research the treatment algorithms indicated for patients with PAH and understand specific treatments in detail To gain some insight into recent clinical developments regarding PAH. “This site was made by a group [link to the Contributions page listing all of you] of University of Edinburgh medical students who studied this subject over 10 weeks as part of the SSC [link to the SSC web pages]. This website has not been peer reviewed. We certify that this website is our own work and that we have authorisation to use all the content (e.g. figures / images) used in this website. Tutor: Dr. Pallavi Bedi & Dr. Punit Bedi Total website word count: 10457 Word count minus Contributions page, References page, Critical Appraisal Appendix, Information Search Report, Word Version appendix and other sections clearly marked as Appendices: 6250 WordPress Word Count (not including text in images and tables): 5983 Epidemiology Data collected by the SPVU indicates the prevalence and annual incidence of PAH to be 26 and 7.6 cases per million of the population respectively, both of which have increased in recent years.9 Global prevalence is difficult to estimate, but is much higher due to at-risk groups such as those infected by HIV.10 Registry data indicates a higher incidence of PAH in females than males, with up to 70-80% of all PAH patients being female.11 This ratio has increased over time12 and is influenced by factors including geography, aetiology and age13 - the ratio being closer in elderly patients than in those who are younger.14 This difference may be partly due to the fact men tend to die earlier from the disease.15 Older patients experience a longer duration of symptoms before diagnosis when compared to younger individuals.16 Presentation also varies with age, possibly due to the different aetiologies underlying the disease - elderly patients are more likely to suffer from PAH secondary to connective tissue disease or congenital heart disease, whilst younger patients are more commonly diagnosed with idiopathic PAH. 16 Overall, the prevalence of PAH in over 65s is rising, with the disease being increasingly diagnosed in older patients.12 Survival rates of PAH patients show a general improvement,11 although age-related differences do exist.14 Table 1. Epidemiology of PAH:17 Subcategory of PAH % Idiopathic 34.0 Heritable 1.5 Drug induced 0.7 Connective tissue disease 28.0 Congenital heart disease 30.0 Portal hypertension 3.6 Haemolytic anaemia 1.2 HIV 0.9 PPHN 0.1 Classification Pulmonary Hypertension is defined as a sustained elevation of mean pulmonary arterial pressure of >= 25mmHg.1,2 The WHO classifies pulmonary hypertension into five groups:18,19 WHO Group I – Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH) i.e. caused by a progressive increase in pulmonary vascular resistance. WHO Group II – Pulmonary Hypertension owing to left heart disease i.e. caused by left heart failure (systolic, diastolic or valvular dysfunction) WHO Group III – Pulmonary Hypertension owing to lung disease and/or hypoxia i.e. COPD, Interstitial lung disease WHO Group IV – Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension CTPH would have the same features as PAH – origin is vascular. WHO Group V – Pulmonary Hypertension with unclear and/or multifactorial mechanisms Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension is generally categorised as both Groups I and IV, as these are both pre-capillary conditions – i.e. their mean pulmonary artery occlusion pressure is =< 15mmHg – and the pulmonary hypertension is vascular in origin. Groups III and V, although considered pre-capillary, are caused by lung disease or have unclear mechanisms respectively, therefore are not generally categorised as PAH. As Pulmonary Hypertension owing to left heart disease presents with a pulmonary wedge pressure of >15mmHg, it is considered a post-capillary condition and hence it is not classified as PAH. What is the Pulmonary Arterial Occlusion Pressure? The pulmonary wedge pressure is an approximation of left atrial pressure, with normal physiological values of 6-12mmHg.19 This is measured at the pulmonary artery. A catheter is inserted via the internal jugular, subclavian or femoral vein, and advanced through the right heart until the tip lies in the pulmonary artery. A small balloon at the end of the catheter is then inflated and the pressure through the central lumen is measured.19 Figure 1: Right heart catheterisation. Drawn by Dennis Walzl; adapted from Walker et al. (2014) Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine19 During left ventricular failure the occlusion pressure can exceed 30mmHg,19 so this would confirm PH owing to left heart disease, and the resultant left atrial pressure. However, as all other classifications (including PAH and CTPH relating to vascular resistance) have a normal occlusion pressure of <=15mmHg, this excludes that the underlying cause relates to back pressure from the left atrium. Step-by-Step Diagnosis Figure 2 : Algorithm for the diagnosis of PAH Clinical History Symptoms of PAH are difficult difficult to detect because the symptoms are very similar to those of respiratory and cardiac conditions.19 Symptoms include dyspnea, fatigue, weakness, chest pain, leg oedema or syncope. Family history may be relevant as there is a recognised genetic component to PAH.20,21 Signs on physical examination may include increased pulmonary component of second heart sound which reflects dysfunction in pulmonary valve closure, a palpable left parasternal heave which indicate increased pressure in the right ventricle. An elevated jugular venous pressure is suggestive of tricuspid regurgitation.19,22 Suspicion of PAH Echocardiogram (ECG) Right heart enlargement and dilatation are characteristic of PAH and these abnormalities will show up on ECG.19 Right-axis deviation is seen 79% of patients with idiopathic PAH.23,24 Elevated P-waves indicates right atrial enlargement. Even though the ECG is very informative, it lacks sensitivity towards the diagnosis of PAH. Chest X-Ray (CXR) Identify abnormal anatomical factor (e.g. enlarged or displaced heart or abnormal blood vessels) that may suggest pulmonary hypertension.23,25 Doppler Echocardiography The most reliable non-invasive procedure in determining the likelihood of PAH.25 Tricuspid regurgitation (TR) is where there is dysfunction in the closure of the tricuspid valve during systole.22,26 This is common in PAH patients, which aid the measurement of pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) using the following simplified Bernoulli equation.19 The TR jet is present in only about 74% of patients.25 There are positive correlations between these readings and the pressure measured during right sided heart catheterisation, yet they are not strong enough and the true value of the pulmonary arterial pressure may need to be confirmed invasively.25 Establishing specific diagnosis & determining prognosis The Right Heart Catheterisation (RHC) is the gold standard for diagnosis of PAH. RHC is an invasive procedure,20 aimed at directly measuring the pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP), cardiac output, right atrial pressure (RAP) and pulmonary venous pressure. The information obtained from the procedure also gives a rough idea on the prognosis of the disease and this guides the therapy and management plans for patients.20,21 Functional assessments 6-minute Walk Test (6MWT) Functional assessments are useful tools to determine the baseline tolerability of any physical activity following treatment.21 Patients are asked to walk on flat or inclined surface for a duration of 6-minutes, and at the end of the test, vital clinical signs such as oxygen saturation, heart rate and dyspnea are assessed. The results from the test, if obtained regularly, provide important information such as patient response to therapy or to determine clinical worsening to the disease.21 ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY VS. RIGHT HEART CATHETERISATION The use of either echocardiography or RHC as a diagnostic tool for pulmonary hypertension has been a debatable issue. We have identified 10 relevant studies that compare the use of echocardiography and RHC as a diagnostic tool via literature search engines such as Medline, PUBMED and Google Scholar. The papers were analysed for comparisons between the measurements of pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) from echocardiography versus RHC in the diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. The Bland and Altman analysis is a statistical test used to compare methods of measurements, and was used in most of the studies. The results are shown in the data table. DISCUSSION Out of the 10 studies analysed, 5 came to the overall conclusion that RHC was still necessary for a reliable diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension. Three studies, those with the highest correlation coefficients between echo and RHC, came to the conclusion that RHC was not necessary. In the paper by D’Alto et.al, the measurements from echocardiography were found to be accurate but with a low precision.28 Accuracy refers to the deviation of the obtained measurement from the true value. If a group of results are accurate then they will together be close to the true value and therefore can be useful in population studies. Precision refers to the consistency of results when the same test is repeated numerous times. In echocardiography, the results are less precise, making this a more inappropriate test for the diagnosis of PAH in patients. The likelihood of misdiagnosing a patient is higher if readings are imprecise.28 Echocardiography is known as an inexpensive, easily accessible and noninvasive procedure. Echocardiography most commonly uses the simplified Bernoulli equation to calculate the pulmonary arterial pressure.36 The application of this equation is based on assumptions and this might result in a significant error in the calculations.37 In the study by Skjaerpe et al., the peak pressure drop from right ventricle into right atrium during heart contraction was calculated from the simplified Bernoulli equation to identify presence of tricuspid regurgitation (TR). In patients with mild TR with a small area of valve regurgitation, the correlation between measurements of echocardiography and RHC was high (r=0.95, Standard error of estimation ±5-1 mmHg), which may suggest that the use of simplified Bernoulli equation in mild cases may be highly accurate.35 The disadvantage of using the Bernoulli equation in echocardiography is that it requires a measurement for the TR jet, something that is not present in all patients.25 On the other hand, RHC is invasive but known to be highly accurate and is used as the gold standard to diagnose PAH. However, there are limitations to the procedure as readings taken are obtained ONLY at rest, in the supine position. This may incorrectly reflect haemodynamic responses during exercise.24 Note that the Doppler echocardiography can be performed during exercise to estimate PAP, which can be a useful tool in the evaluation of right ventricular systolic pressure response during exercise.20 To conclusively prove that echocardiography is as reliable as RHC in the diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension would have significant advantages, both to the safety of the patient as well as to the cost of diagnosis. This could be the reason there are so many comparative studies between echocardiography and RHC. It is important to consider that there may be bias in these studies due to the motive to conclude that echocardiography is equally reliable. Table 3 : Summary of Advantages and Disadvantages of Echocardiography and RHC Echocardiography Advantages Disadvantages non-invasive inexpensive accessible can be used to monitor disease progression over time low precision the most commonly used method requires the TR jet, not present in all patients Right HeartCatheterisation(RHC) high accuracy high precision invasive expensive patients more likely to refuse procedure Click to enlarge Treatment Overview The current treatment guidelines for PAH are goal-orientated where treatment goals are based on achieving or maintaining particular thresholds or values in parameters known to be prognostically relevant.38 Therefore the initial clinical assessment of the patient is critical in the choice of treatment, the evaluation of response to therapy, and the escalation of therapy if necessary. Patients are categorised by the clinical severity of PAH, using the WHO Functional Classification.38,39 This is modified from a system originally developed for heart failure by the New York Heart Association (NYHA). This system links activity limitations and symptoms, allowing clinicians to predict disease progression and prognosis, as well as the need for specific treatment regimens.38 Functional Class Symptomatic Profile I Suffers with PAH but no consequent limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity does not cause dyspnoea or fatigue, chest pain, or faintness II Has PAH resulting in slight limitation of physical activity. Comfortable at rest but routine physical activity causes dyspnoea or fatigue, chest pain, or faintness III Has PAH resulting in marked limitation of physical activity. Comfortable at rest. Less than regular activity causes dyspnoea or fatigue, chest pain, or faintness IV Has PAH with inability to carry out any physical activity without symptoms. Manifest signs of right heart failure. Dyspnoea and/or fatigue may even be present at rest and discomfort is increased by any physical activity Patients are treated using the general algorithm below. The goal for all treatments is that patients to improve to WHO FC II or better, which is associated with a significantly better prognosis and survival rate.40 Other functional parameters which are measured include the six-minute walk test, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, haemodynamic/vasoreactivity testing) and biochemical markers.39 If improvements in functional or physiological parameters are not seen, then escalation of treatments, including combination therapies and surgery, should be considered.39,41 The goals for the treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension aim to: promote vasodilation, suppress cell proliferation, and induce apoptosis within the pulmonary artery wall.42 Treatment for PAH is split into two types of therapy: background therapies (which includes general measures) and targeted therapies.43 Figure 3 [click image to enlarge] General Measures and Background Therapy This includes non-medicinal therapy to try to minimise symptoms alongside nontargeted drugs pulmonary hypertension. Such drugs include:43 Diuretics to reduce right ventricular volume overload and right sided heart failure Anticoagulants (unless there is an increased risk of bleeding) Digoxin for use in patients who develop atrial tachyarrhythmias. Some non-medicinal therapies and advice include:43 Basic counselling and disease state education Low level aerobic exercise Benefits of intensive pulmonary rehabilitation have been demonstrated Heavy physical exertion and isometric exercise (where joint angle and muscle length doesn’t change) are ill advised Oxygen supplementation in order to maintain saturation above 90% Sodium restricted diet- particularly in those with RV failure to manage volume Routine immunisations, e.g. against influenza and pneumococcal infection Therapy should be individualised for each patient taking into account a number of factors including: Severity of illness Route of administration Side effects Comorbid illnesses Treatment goals In this section we will review targeted therapies. The pathways of some of these therapies are illustrated in the diagram below: Figure 4: Targets for Current or Emerging Therapies in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Reproduced with permission from Humbert et al. Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. 44 Copyright Massachusetts Medical Society Calcium Channel Blockers (CCBs) reduce the contraction of smooth muscle in arteries therefore increasing arterial diameter.43 CCBs may be effective for patients with a positive response to pulmonary vasoreactivity testing.43,63 This establishes the relative contribution of reversible vasoconstriction verus fixed stenosis in patients with PAH.63 If patients have significant reversible vasoconstriction, they could benefit from the long-term use of calcium channel blocker therapy. Vasoreactivity testing generally is performed during right heart catheterisation for PAH diagnosis.41 20ppm of inhaled nitrogen oxide is administered, and the pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) is measured. For a positive result the patient would have a drop in the mean PAP of at least 10mmHg to a value below 40mmHg, with no decrease in cardiac output. About 10-15% of patients with IPAH have a positive test.63 If the patient doesn’t improve sufficiently (to class I or II) on calcium channel blockers an alternative PAH therapy should be prescribed.43 Patients that have a negative test result are not only unlikely to experience any benefit from CCBs but there is also a high chance of them suffering adverse effects.63 Very few patients with IPAH do well over the long term on CCBs (no more than 5%)64 but the vasodilator testing identifies those who may actually benefit from this treatment.63 Examples of CCBs used are: Nifedipine Diltiazem Amlodipine A review by Humbert et al. found that high dose CCBs, including diltiazem, nifedipine and amlodipine, can have the effect of prolonging survival in those patients who respond to treatment.44 Relatively few patients do respond (approximately 10%), somewhat limiting their use. Patients who respond to treatment can be found by performing an acute vasodilator challenge. CCBs should not be used as first line treatment; rather, it is a possibility for long-term treatment for some patients.44 However, the evidence supporting the use of CCBs is limited. There is no randomised data concerning their use in PAH. An early study by Rich et al. showed a marked improvement in mortality of patients who responded to CCB treatment compared to that of patients who did not.65 This data is limited by sample size (n=64); moreover, it is possible that "responders" have better prognoses because of confounding factors, rather than the effect of CCBs. More recent evidence for the use of CCBs includes a retrospective trial by Sitbon et al. (n=557), in which responders to CCB treatment showed greater decreases in pulmonary arterial pressure and peripheral vascular resistance, as well as significantly reduced mortality.66 This data is, however, limited by the retrospective nature of the trial, as well as by the small number of subjects that showed long-term CCB response: of 70 patients on whom long-term CCB treatment was initiated (after acute pulmonary vasoreactivity testing), only 38 showed improvement. Moreover, the study only considered patients from one institution. Thus, it is clear that CCBs can be useful in treating those patients who respond to them. However, there is a need for more high-quality studies, including randomised controlled trials, to establish an adequate evidence base for their use. Some of the side effects associated with CCBs include headache, flushing, ankle oedema, tachycardia and hypotension.43 Endothelin-1 plays a major role in vascular tone and in PAH it has been shown that it is quite often over expressed in the plasma.45 It acts as a vasoconstrictor and also stimulates cell proliferation.43 ERAs act by selectively blocking the endothelin A and B receptor sites. 43 This prevents the production of endothelin-1. Figure 5: Endothelin pathway. Drawn by Dennis Walzl. Some examples of ERA include: Bosentan This drug is well studied and non-selective (it blocks both A and B receptor sites).43 It is also quite commonly used to treat PAH. Gabbay et al. reviewed a number of studies following patients which were WHO functional class III and IV at baseline.46 The papers reviewed showed Bosentan to be effective in improving exercise capacity, WHO FC, cardiopulmonary haemodynamics, quality of life and also delaying time to clinical worsening when compared to the placebo group.46 The largest of these (Rubin et al. 2002) was a placebo controlled double blinded study of 213 patients. It found that at 16 weeks, treatment with Bosentan improved the 6MWT results by 44 meters or more. Furthermore, it was found to improve WHO functional class and delay time to clinical worsening.46 As none of the trials were designed to include survival benefit, comparisons were made with historical controls and NIH registry data to provide an idea of survival benefit of Bosentan. The Kaplan-Meier survival estimate at two years was 89% for patients treated with Bosentan and 57% for those not. Although the data is not reliable.46 Like most of the drugs mentioned there can be adverse effects such as headache, anaemia and oedema. Furthermore, whilst the patient is taking Bosentan they have to have monthly liver function tests. 43 Macitentan This is again a non-selective drug similar to Bosentan but it has increased tissue penetration and also has a more sustained effect. 43 The efficacy, safety and pharmacology of Macitentan was reviewed by Hong et al. in 2014.47 Two trials assessed the efficacy and safety of Macitentan. One of which (a phase 3 trial called Seraphin) evaluated its efficacy in treating PAH, with particular respect to clinical PAH worsening and all-cause death. Seraphin involved 742 patients in either a Macitentan 10mg group, a Macitentan 3mg group and a placebo group, randomised 1:1:1. This trial was conducted over a median period of 115 weeks and showed that Macitentan 10mg and 3mg daily had a significant effect in reducing morbidity and mortality.47 The review concluded that although “further comparative studies are necessary to ascertain its pace in therapy”, Macitentan may have fewer contraindications than its counterpart ERAs as well as being available to those with hepatic impairment.47 Again it can cause adverse effects, for example headache, anaemia and nasopharygitis, however, unlike bosentan patients who are taking this drug do not require monthly liver function tests.43 Ambrisentan This drug selectively blocks only A receptor sites.43 Several trials have shown Ambrisentan to be an effective long term treatment for PAH. Peacock et al. found that Ambrisentan significantly improves exercise capacity over a 12 week period as well as sustained improvements over 2 and 3 years.48 One trial reviewed by Peacock et al. (ARIES-E) found that the WHO Functional Class was maintained or improved in 7989% of patients at two years. Furthermore, improvements in exercise capacity and cardiopulmonary haemodynamics were observed when Ambrisentan therapy was combined with background PDE5i therapy.48 The sample sizes for the various studies were of varying sizes, N=383 being the largest sample of cases for the extension of ARIES1 and ARIES2. The small Japanese study only used 25 cases48 and this could have led to chance potentially affecting the results. Side effects can include fluid retention, nasal congestion, flushing and anaemia. Similarly to Macitentan, patients on this drug do not require monthly liver function test.43 There are two groups of drugs used that act on the Nitric Oxide Pathway. These are: Phosphodiesterase Type 5 Inhibitors Soluble Guanylate Cyclase Stimulators Figure 6: Nitric oxide pathway. Drawn by Dennis Walzl. Phosphodiesterase Type 5 Inhibitors These are vasodilators that also have anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects.42 They induce vasodilation by inhibiting the hydrolytic breakdown of Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate (cGMP).49 Sildenafil Trials such as the one completed by Garg et al. have demonstrated that patients using Sildenafil have significant improvements in the 6MWD and also haemodynamics, functional capacity and arterial oxygen saturation.43,50 Wang et al. carried out a systematic review of the effectiveness of Sildenafil in 2014. They reviewed studies involving a total of 545 patients, 342 of which received Sildenafil, the rest placebo. Four multicentre, double-blinded randomised control trials were included in the metaanalysis. They found sildenafil to be effective in reducing TTCW (9% in Sildenafil group as opposed to 5.7% in the placebo group) as well as improving 6MWD, WHO FC, quality of life and haemodynamics.50,51 However, no significant difference was found in the likelihood of mortality between the two groups. Furthermore, the small sample size and different methodologies between studies could create discrepancies in the metaanalysis.51 Tadalafil This can improve the patients 6MWD and a high dose of this drug has also been found to improve the patient’s TTCW.43 This was demonstrated in a large study undertaken by Croxtall et al. This study was randomised, multi-centred, double blinded and placebo-controlled phase III trial therefore making it less likely to be affected by chance or other outside factors.52 Furthermore, in 2015 Henrie et al. reviewed the effectiveness of Tadalafil in both mono and combination therapy. Reviewing monotherpy for Tadalafil in phase I, II and III trials they found Tadalafil 40mg to be effective in improving 6MWD for prolonged periods of time as well as improving cardiopulmonary haemodynamics, TTCW and quality of life. 53 The largest monotherapy trial being a phase III trial called the PHIRST trial and its 52 week extension starting in 2009. A randomised double blind, multicentre, placebo controlled trial of 405 cases for the initial trial and 357 who continued therapy into the extension project. They found evidence of combination therapy to be lacking, although there appeared to be potential benefits from using Tadalafil in combination with Bosentan and more promisingly, Ambrisentan due to lack of CYP3A induction (CYP3A clears Tadalafil).53 Adverse effects were found to not be major with headache being the most common. Other side effects included flushing, myalgia and epistaxis but apart from this the drug appeared to be well tolerated.43,53 Soluble Guanylate Cyclase Stimulators These increase cGMP production by directly stimulating Guanylate Cyclase independent of Nitric Oxide availability.43,54 Riociguat Riociguat has a dual mode of action, it directly stimulates Guanylate Cyclase independent of Nitric Oxide and also acts with endogenous Nitric Oxide. Furthermore, it increases sensitivity of soluble Guanylate Cyclase to Nitric Oxide. Some adverse effects that can be experienced include syncope, headache, dyspepsia, peripheral oedema and hypotension.43,54 Several trials have been undertaken regarding Riociguat and its effects. In 2012 Lasker et al. reviewed the use of Riociguat in one phase I and one phase II trial. They found Riociguat to be effective in significantly reducing Pulmonary Vascular Resistance, mean Pulmonary Arterial Pressure and Cardiac Index in patients with PAH as well as having only minor side effects. The phase II group also showed significant improvement in 6MWD.55 However, the study found that there were large variations in plasma concentration for similar doses of drug suggesting titration would be of importance in a clinical setting. Furthermore, Riociguat causes systemic as well as pulmonary vasodilation, so it was noted that individualised doses would be necessary to limit these side effects.55 Sulica et al. provided information from a small study (N=3) of the effects of Riociguat in PAH FC III patients. The study showed improvements in all patients in terms of optimising haemodynamics and functional parameters.56 Having said this the study was extremely flawed. The sample size of only three cases meant that the effects of chance could have had a considerable effect on the results and hence the results are likely unreliable. Furthermore, the absence of a control group as well as several uncontrolled confounders are likely to have also affected the results decreasing reliability.56 Prostacyclin Analogues This is the only monotherapy that has approved which has a positive impact on longterm survival. Furthermore, it has anti-proliferative, endothelial regeneration and antiinflammatory effects.57 Prostacyclin (PGI2) is released by healthy endothelial cells and has a paracrine effect on nearby platelets and endothelial cells causing vasodilation and antiproliferation as well as antithombolitic effects.43 Prostacyclin analogues have been the backbone of PAH treatment for about 2 decades,43 however, they are very hard to work with due to their short half-lives.57 This has lead chemists to create a series of compounds that have a longer half-life and are less susceptible to hydrolysis. Prostanoids are complex therapies and best administered by a centre with expertise.43 Some examples of prostacyclin analogues that used to treat PAH are: Epoprostenol This drug will allow the patient to increase their exercise tolerance while also improving haemodynamics and quality of life. The patient is given it via continuous IV infusion so they have to be educated in the proper way to prepare and administer this drug.43 In 2015 Akagi et al. reviewed the effectiveness of Epoprostenol in the treatment of various types of PAH.58 Through examining various studies they found epoprostenol to be an effective treatment for patients with severe PAH, having numerous positive effects including improving 6MWD, reducing PVD and markedly improving haemodynamics, particularly in relation to reverse remodelling effects on pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Epoprostenol therapy does however have a number of complications, the most serious of these being the risk of catheter-related infection.58 Some other side effects include jaw pain, flushing, nausea, diarrhoea, rash and muscle pain.43 Furthermore, Epoprostenol was found to often affect the systemic vascular bed more than he pulmonary. This can therefore lead to severe systemic hypotension. It is therefore important to prevent haemodynamic instability. 58 Treprostinil This drug is administered by subcutaneous injection or inhalation. 43 A study to determine the safety and efficacy of the drugwhen taken in combination with a background therapy of ERA and/or PDE-5 inhibitor found an improved 6MWD from baseline after 16 weeks.59 However, this cannot be considered statistically significant due to the high rate of discontinuation. The 22% drop out in patients receiving oral treprostinil was largely due to the presence of adverse effects or clinical worsening, which was more common at higher doses, suggesting the lack of tolerability to the drug. When another similar study was conducted, with lower doses to improve tolerance, no statistically significant changes in 6MWD, WHO FC or dyspnoea fatigue index score were found.60 Conversely, the FREEDOM-C trial made statistically significant findings regarding differences in dyspnoea fatigue index scores when comparing oral treprostinil to the placebo group. However, the trial was limited in its longer-term observations beyond 16 weeks.59 Its use as a monotherapy is much more effective as suggested in the FREEDOM-M trial, which found that 52% of treated patients demonstrated at least a 20m improvement in 6MWD after 12 weeks.61 However, this trial also lacked information regarding long term use. A longer study could’ve been used to address clinical worsening and survival. Some of the adverse effects experienced included pain and erythema at the site of the injection, headache, diarrhoea, rash and nausea or for inhaled treprostinil common side effects include cough, headache, nausea, dizziness and flushing. 43 Iloprost This drug is also inhaled and will improve the patients functional class, 6MWD and TTCW.43 In 2009 Olschewski reviewed inhaled iloprost use across a number of trials. Overall iloprost was found to be effective in improving 6MWD, NYHA Functional Class, cardiopulmonary haemodynamics as well as improving Mahler dyspnoea score and quality of life.62 This was found in two 12 week randomised control trials with a placebo group control. The first of which (AIR) was blinded, where 203 patients with severe PAH and chronic thromboembolic PH in NYHA class III and IV measured the efficacy of iloprost monotherapy. The second (STEP) measured the efficacy of iloprost when combined with bosentan in 67 patients, again in a randomised control trial with a placebo group control, this time however, it was open.62 Further long term studies also showed the efficacy of iloprost over the following years. One of these trials was a longterm open-label extension of the AIR study. This study showed NYHA functional class improved in 41% and 76% of patients with inhaled iloprost after 1 and 3 years. One trial, the COMBI trial, did fail however, having to be discontinued early due to predicted failure.62 This however, could have been due to numerous factors with small sample size, the open-label design and the severity of the disease at the time of onset being foremost amongst these. Overall Olschewski concluded that iloprost is effective in treating patients with PAH; particularly in those with NYHA functional class III and IV, and that the drug has a favourable safety profile.62 Common side effects include cough, headache, flushing and jaw pain.43 Surgical Treatments Atrial Septostomy During this procedure a catheter is inserted into the internal jugular vein in the patient’s leg and then threaded up to their heart. The catheter is then inserted into the atrial septum where a small balloon is inflated creating an opening between the atria. This procedure creates a right to left intracardiac shunt, relieving the pressure in the right atria and increasing the blood flow. In a study completed by Riechenburger et al. it was found that atrial septostomy improved clinical and haemodynamic function with the possibility of effecting the patient’s prognosis.67 However, in this study it is used as a palliative measure in patients with severe PAH, i.e. The patient is continuing to deteriorate despite drug therapies. Furthermore, the highest mortality rate for this intervention is early post-procedure and the sample used for this study was relatively small meaning that results may have been affected by chance. Lung transplant A lung transplant is currently the only available curative treatment for PAH, 67 although the introduction and increasing use of disease targeted therapy has caused a delay and reduction in the number of patients being referred for transplant.68 It is mainly used for patients that do not improve on drug therapy (after receiving both monotherapy and maximal combination therapy), remaining in WHO FC III or IV. Once a patient has received the transplant their 5-year survival rate is approximately 45-50% accompanied with a generally good quality of life.68 Future Perspectives Diagnosis Through our comparisons between right heart catheterisation (RHC) and echocardiography it seems clear that RHC will remain gold standard procedure for detecting pressure. Many other modalities in the estimation of haemodynamics of the lungs are continually being investigated. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a new alternative to echocardiography that is becoming increasingly more accepted. The advantages of MRI are that it provides a high contrast resolution image, can investigate a wide range of haemodynamic factors, does not expose the patient to ionising radiation and it is a non-invasive procedure.69 There are a range of ways in which MRI can be used to investigate pulmonary hypertension, including assessment of lung volume or assessment of biventricular mass, volume and function. Phase contrast MRI (PC-MRI) is one example of a performed technique.69 PC-MRI is a technique that visualises fluid movement by comparing its’ movement to stationary tissues.70 PC-MRI can be used to investigate cardiac output and flow, as well as pulmonary artery stiffness and pulsivity.69 We considered a study comparing the use of PC-MRI with RHC and echocardiography with RHC, in order to estimate pulmonary flow and pressure in PAH. The study found that PC-MRI had a greater compatibility to RHC in comparison to echocardiography, with correlation coefficients of 0.94 and 0.86 respectively.71 It was acknowledged that inter- and intraobserver variability had not been assessed in this small study. However a literature review of MRI in the diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension concluded that inter and intraobserver variability was significantly less in MRI than echocardiography as a result of higher rates of precision.69 In general, MRI appears to have an accuracy that is better or at least comparable to echocardiography, as well as higher levels of precision. 69 Further study in a clinical environment may be needed as MRI appears to be a very plausible new alternative in the diagnosis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Treatment and Prognosis Overall, there has been an profound improvement in survival of patients diagnosed with PAH. This has been mainly due to treatment, although it could also be related to earlier diagnosis. It has been reported that the three year survival rate has increased to 83% whereas the median survival time was previously limited to 2.8 years.5,6 However, despite improvements the treatment options for PAH still remain limited when compared to other conditions and there is still no cure. Conclusion Our project has drawn several key conclusions regarding the diagnosis and treatment of PAH. Recent developments in treatments for the condition have been lacking. Those that have been produced are primarily symptom-relieving and aim to improve quality of life, rather than being curative measures. The implication of this for patients with PAH is that prognosis remains poor, despite improvements in clinical worsening and exercise tolerance. Surgical treatments are a last resort and there are few donors, meaning there is a clear requirement for alternative therapies. With regards to diagnosis, the use of MRI is becoming more prominent due to its noninvasive nature. It could, to a certain extent, be replacing echocardiography due its greater accuracy and precision. The definitive diagnosis of PAH remains the use of right heart catheterisation, although a detailed history, physical examination and other clinical investigations are useful and important. However, diagnosis is difficult in the early stages of disease as the symptoms show significant overlap with other cardiovascular conditions. This has negative implications for patients as later diagnosis results in significantly worse prognosis. Overall, the group have gained a much greater insight into several aspects of this debilitating disease. We are pleased with the outcome of the project and have managed to address our original aims and objectives. However, if not constrained by time we would have liked to look further in to future perspectives as there is great breadth for advancement in treatment.