Proceedings (DOC) - Food and Agriculture Organization of the

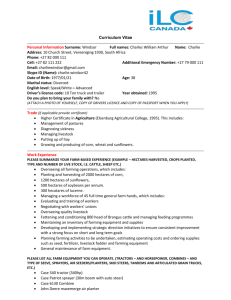

advertisement