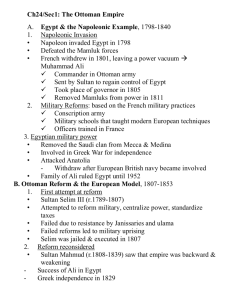

GREGORY Middle East#1 - Geographical Imaginations

advertisement

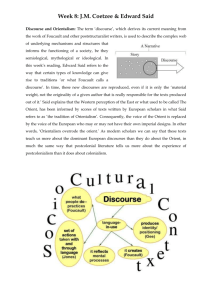

Middle of what? East of where? Derek Gregory ‘I do not divide the world between East and West. They call us the Middle East, but middle to whom? When I come to England I say I am coming to the Middle West. When I go to America I say I am going to the Far West. We have to have the courage to change the language.’ Nawal El-Saadawi I suspect that speaking of ‘the Middle East’ is, to most people in Europe and North America, unexceptional. For them it has come to function as a commonplace signifier of an uncommon place, a term that conjures up a series of images that validate the assumptions that bring it into being. In the face of such casual ascriptions Egyptian writer Nawal El-Saadawi’s question is a sharp one. To ask: ‘Middle of what?’ – and ‘East of where?’ – is to draw attention to the privileges and powers that are written into our imaginative geographies. These are ways of mapping the world that separate ‘our’ space, almost always the space from which we map, and ‘their’ space’, the space that we most urgently need to map. The cartographic metaphor reveals a dialectic of subject and object, activity and passivity, that animates a process of imaginative possession – to know in something like the Biblical sense of the word – and while there are counter-cartographies that address other, reverse and even reciprocal ways of knowing, often trafficking in the increasingly busy straits between art and cartography, these interventions are driven by the imperative to break the spell cast by the conventional imaginative geographies that we routinely invoke to categorise and partition, navigate and shape the world. These are never innocent constructions; like all images, words have the capacity to make the world visible like this (but 1 not like that), and to license our acting like this (but not like that). Yet even scholars whose politics and sympathies differ sharply find common ground in their objection to the term ‘Middle East’. Bernard Lewis describes it as ‘meaningless, colorless, shapeless, and for most of the world inaccurate’, while Rashid Khalidi complains that it is ‘Eurocentric, non-geographical and inherently meaningless’. Although ‘Middle East’ has gained currency within the region itself, translated into Arabic as al-sharq al-awsat, it is thoroughly counterfeit. 1 In this short essay I want to show how, for this very reason, the term has been used as a means of (unequal) exchange in a series of historical transactions. *** The ‘Middle East’ – and the associations and assumptions that are smuggled into the world under its luggage label – has its origins in European and eventually American discourses of diplomacy, geopolitics and security, and in a more diffuse cultural register in Euro-American imaginative geographies of a largely Arab and Muslim ‘Orient’. The two cross-cut in complex ways, but their modern history begins with Napoleon Bonaparte’s military expedition to Egypt in 1798, which was in some measure part of a plan to cut Britain’s lines of communication with its empire in India, and in the bloody but short-lived campaigns he fought through Syria. In invading Egypt, Juan Cole argues, ‘Bonaparte was inventing what we now call “the 1 Bernard Lewis, The multiple identities of the Middle East (New York: Schocken, 1999) p.9; Rashid Khalidi, Sowing crisis: the Cold War and American dominance in the Middle East (Boston: Beacon Press, 2009) p. 264, note 3; see also his ‘The “Middle East” as a framework for analysis: re-mapping a region in the era of globalization’, Comparative studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 18 (1) (1998): 1-8. 2 modern Middle East”’, and – Cole was writing in the shadow of the American and British invasion of Iraq in 2003 – ‘the similarities of the Corsican general’s rhetoric and tactics to those of later North Atlantic incursions into the region tell us much about the persistent pathologies of Enlightenment republics.’ 2 So they do, but Napoleon’s campaigns were not only political and military adventures; they were also moments in the advance of a cultural imperialism. This is why Edward Said located the formation of a distinctively modern Orientalism in the textual and visual appropriations of Egypt made for a European audience by the scientists, scholars and artists whom he had accompany his troops. 3 Orientalism was a cultural repertoire, a more or less theatrical performance activated in books, paintings, museums, opera and eventually film and other media, that characterised and caricatured particular peoples and places. But it was also more than this. When Said described Orientalism as a discourse he was calling attention to its performative power, which is to say its capacity to produce the very effect it names (‘the Orient’). That capacity was – and remains – contingent. It depends on the constellations, conjunctures and circumstances in which Juan Cole, Napoleon’s Egypt: invading the Middle East (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007). I say ‘distinctively modern’ because there were, as Said shows, much older versions of Orientalism that reach back to the classical world and the chronic antagonisms between the Greek city-states and the Persian empire. Said does not treat Orientalism as unchanging, therefore, but is concerned to trace its historical curve and, in particular, its modern genealogy. This does not mean that the world changed forever in 1798, any more than it did in 2001, and there are also powerful continuities. Said argues that Aeschylus’s Pericles and Euripides’ The Bacchae established two ‘essential motifs’ in European imaginative geography. First, ‘a line is drawn between two continents. Europe is powerful and articulate; Asia is defeated and distant.’ But second, even as Europe articulates this Orient, its capricious object always threatens to exceed the space of its articulation and articulates ‘the motif of the Orient as insinuating danger’. See Edward Said, Orientalism (London: Penguin, 1978) p. 57. 2 3 3 Orientalism is activated. Said focused on its entanglements with British, French and American modalities of power and on their collective (but none the less variable) production of a particular ‘Orient’: the Arab ‘Middle East’. There were other modalities – German and Italian, for example – and other ‘Orients’, including India, China and Japan. But for reasons intimately bound up with his identity as a Palestinian-American, born in Jerusalem and living in New York, Said focused on two command performances that, in different but none the less repetitive forms, displayed and domesticated this place. First, ‘the Orient’ was summoned as an exotic and bizarre space, and at the limit a pathological and even monstrous space: what he called ‘a living tableau of queerness.’ 4 Different versions of this fascination – and on occasion revulsion – run right through the writings that were Said’s principal concern in his critique of Orientalism, a realm of bourgeois or high culture, and they reappear in more popular forms like nineteenth-century music hall, twentieth-century Hollywood films, and twenty-first century graphic novels. But Said’s point was much sharper than a rejection of racism. For him, Orientalism underwrote and in an important sense prepared the ground for a peculiarly colonizing form of power. The link between literature – Said’s own field – and colonizing power has been expressed with a special economy by Timothy Mitchell. Writing of the British and French colonial project in Egypt, he explained that ‘colonial power required the country to become readable, like a book, in our own sense of such a term.’ This was, as Mitchell shows, an extraordinary way of seeing and setting up the world – what he calls ‘the world-as-exhibition’ – that made ‘their’ space not only legible but also calculable. ‘Egypt was to be ordered up as something 4 Said, Orientalism, p. 103. 4 object-like, he explains. ‘In other words it was to be made picture-like and legible, rendered available to political and economic calculation.’ 5 This was the second command performance made possible by (and through) Orientalism. The Orient’ was constructed as a space that had to be domesticated, disciplined and normalized – ‘straightened out’ – through a forceful projection of the order it was presumed to lack: ‘framed by the classroom, the criminal court, the prison, the illustrated manual.’ 6 These twin performances did considerably more than epistemological violence. The Orientalist projection of order was more than conceptual or cognitive, for the process of ordering also conveyed the sense of command and conquest. Although Said says remarkably little about it, the French occupation of Cairo and the subsequent rampage through Syria were hideously bloody affairs. In fact, David Bell claims that the Napoleonic wars wrought such a transformation in the scope and intensity of warfare that they constituted ‘the first total war’ of the modern period. 7 This probably needs qualification, but the proximity of modern Orientalism to modern warfare is reinforced in other ways too. Said notes more or less in passing that what most impressed the first Arab chronicler of the occupation, Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti, ‘was Napoleon’s use of scholars to manage his contacts with the natives.’ 8 This was expediency more than cultural sensibility; the savants 5 Timothy Mitchell, Colonising Egypt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988); Mitchell develops these themes even more brilliantly in his Rule of experts: Egypt, technology, modernity (Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 2002). 6 Said, Orientalism, p. 41. Converting ‘queer’ into ‘straight’ was only one axis through which Orientalism turned its object into one of desire, at once sexualized and eroticised. 7 David Bell, The first total war: Napoleon’s Europe and the birth of warfare as we know it (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2007). 8 Said, Orientalism, p. 82; Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti, Journal d’un notable du Caire durant l’expédition française 1798-1801 (trans. Joseph Cucocq), Paris: Albin Michel, 5 grumbled that they were required to provide all sorts of practical information for the army on a more or less daily basis and to produce what was, in effect, military intelligence. Neither they nor the troops were prepared for their first contact with Cairo – it resembled ‘a great intestine filled with houses stacked on top of one another,’ complained one officer, ‘without order, without regularity, without method’ (my emphasis) – and so it was necessary to transform its multiple opacities into a singular transparency. This is the characteristically Orientalist gesture – ordering what was assumed (incorrectly, as it happens) to be disordered – and Napoleon was determined that Cairo should be opened to the French military gaze: transformed into a spatialised object of knowledge that would make possible the surveillance, regulation and exaction of the city and its population. Here too there are resonances in our own, I think still colonial present, that also disclose the ‘persistent pathologies of Enlightenment republics’. While Bush’s Baghdad was hardly the Corsican’s Cairo, the US Army had as much trouble reading its flickering signs in 2003 as the French military had had in Cairo in 1798, and it was just as determined to open the occupied city to its invasive (and, as it happens, often cartographic) gaze. 9 *** If the cultural repertoire of modern Orientalism has been activated in support of political-military violence from the late eighteenth through to the 1979. In fact, Jabarti provided three different accounts of the occupation: see André Raymond, Égyptiens et français au Caire, 1798-1801, Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 1998, pp. 3-5. 9 Derek Gregory, ‘Dis/Ordering the Orient: scopic regimes and modern war’, in Tarak Barkawi and Keith Stanski (eds), Orientalism and war (London: Hurst, 2012) pp. 147171; see also Derek Gregory, ‘Seeing Red: Baghdad and the event-ful city’, Political Geography 29 (2010) 266-79. 6 twenty-first century, another term that works with the Orient to triangulate the Middle East – ‘the Levant’ – adds a commercial-economic register that has also remained conspicuously open throughout the period. The term has a long history, though shorter than that of the Orient. By the thirteenth century merchants from Venice and Genoa trading with their counterparts in Constantinople, Smyrna, Alexandria and Aleppo were describing the littoral arc of the eastern Mediterranean as the Levant – like the Orient, from the Latin oriens (rising), the Levant, from the French lever, was the land where the sun rises – but to them its radiance was largely commercial and it illuminated a sparkling necklace of port cities. 10 By the sixteenth century those mercantile bonds had been soldered by a political and military alliance between France and the Ottoman Empire, ‘the union of the lily and the crescent’ as Philip Mansel puts it, which was forged out of their mutual distrust of the ambitions of Charles V’s Holy Roman Empire. This was destined to endure into the early twentieth century, and throughout the period the alliance retained the tensile commercial strength of the original, notably through a series of concessions (or ‘capitulations’) made by Constantinople to French merchants from 1569. 11 10 Commerce between Europe and these lands had a much longer history, and if Michael McCormick is to be believed, it was instrumental in the emergence and (re)formation of a European economy after the fall of the Roman Empire: see his Origins of the European economy: communications and commerce AD 300-900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001). The expansion of Islam did not ‘apply the coup de grace to a moribund late Roman system’, as an older generation of historians had argued, but on his reading ‘offered the wealth and markets which would fire the first [medieval] rise of Europe.’ 11 Philip Mansel, Levant: splendour and catastrophe on the Mediterranean (London: John Murray, 2010); Thomas Scheffler, ‘“Fertile Crescent”, “Orient”, “Middle East”: the changing mental maps of southwest Asia’, European review of history, 10 (2003) 253-72: 261. 7 But the terms of the relationship, which Mansel portrays as one of the most successful alliances in history, were increasingly political, and from the eighteenth century French politicians and diplomats described the Ottoman Empire as la Proche-Orient (‘the Near East’): a term that encapsulated both a physical and a political proximity. This was not a peculiarly French affair. For most of the nineteenth century the Eastern Question that preoccupied high politics across Europe was invariably an Ottoman one, and by the end of the century it was inflected by an increasing rapprochement between Berlin and Constantinople. *** Throughout the nineteenth century British politicians and diplomats kept a close watch on these developments, but their telescopes were also trained – like Napoleon’s at the end of the eighteenth century – on India, and when the ‘Middle East’ emerged as an English-language term of art in the nineteenth century it was in direct relation to British India. 12 Civil servants in the India Office, which had been created in 1858, began to describe Persia and its surrounding regions as ‘the Middle East’, a buffer zone lying not between a ‘Near East’ and a ‘Far East’ but between London and Delhi. The term did not escape from Whitehall to capture more public attention until the beginning of the twentieth century. In 1900 General Sir Thomas Edward 12 Huseyin Yilmaz has traced a much older, more diffuse European genealogy of a ‘Middle East’ in other languages, including references to a medio Oriente in Spanish from the fifteenth century, in Italian and French from the seventeenth century, and to a Mittler Orient (meaning Persia) in German from the nineteenth ccntury: ‘The Eastern Question and the Ottoman Empire: the genesis of the Near and Middle East in the nineteenth century’, in Michael Bonine, Abbas Amanat and Michael Ezekiel Gasper (eds), Is there a Middle East? The evolution of a geopolitical concept (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012) pp. 11-35. 8 Gordon, who had fought in India during the Mutiny and served as Military Attaché and Oriental Secretary at the British Embassy in Tehran, published an essay on ‘The problem of the Middle East’, which he regarded as ‘the cornerstone of the British Empire’. As a soldier, he was concerned above all with the land approach to India through Persia and Afghanistan, but he made no fanfare about the term itself, which he evidently regarded as commonplace in the military and diplomatic circles in which he moved. 13 The same could not be said of an influential essay published in the National Review in 1902 by an American naval officer, Alfred Thayer Mahan. In ‘The Persian Gulf and International Relations’, Mahan argued that British control over the approaches to India was threatened by Russian advances in Central Asia and by the proposed Berlin-Baghdad railway that would bypass Suez and open rival access to the Gulf. 14 Mahan was unaware of Gordon’s essay and, unlike his military predecessor, championed the importance of sea power: ‘The Middle East – if I may adapt a term I have not seen – will some day need its Malta, as well as its Gibraltar; it does not follow that either will be in the Gulf. Naval force has the quality of mobility, which carries with it the privilege of temporary absences; but it needs to find on every scene of operation established bases of refit, of supply, and, in case of disaster, of Thomas Gordon, ‘The Problem of the Middle East’, The Nineteenth Century 47 (1900) 413-424; Karen Culcasi ‘Constructing and naturalizing the Middle East’, Geographical Review 100 (2010) 583-97: 585. 14 Construction of the railway began in 1903, but the project was bedevilled by financial difficulties, technical problems and – by no means least – the First World War; it was not completed until 1940: see Sean McMeekin, The Berlin-Baghdad Express: the Ottoman Empire and Germany’s bid for world power, 1898-1918 (London: Allen Lane, 2010). 13 9 security. The British Navy should have the facility to concentrate in force, if occasion arise, about Aden, India, and the Gulf.’ 15 Almost immediately Mahan’s presumptive claim to the term was registered and popularized by Valentine Chirol, Foreign Editor of the Times, whose career in journalism had started with a brief apprenticeship on the Levant Herald in Constantinople. He wrote a series of articles for the Times that appeared in book form as The Middle Eastern Question, or some political problems of Indian defence (1903). By then, the ‘Middle East’ was envisioned as a security belt on land and on sea running across the northern and western approaches to India, from Persia through Mesopotamia and Afghanistan to Kashmir, Nepal and Tibet; with the conclusion of Chirol’s series the Times removed the scare-quotes from the term. *** These geopolitical warnings – particularly those that drew attention to Germany’s imperial ambitions – were taken very seriously, and Morris Jastow claimed that by the First World War there was a widespread feeling that ‘if, as Napoleon is said to have remarked, Antwerp in the hands of a great continental power was a pistol levelled at the English coast, Baghdad and the Persian Gulf in the hands of Germany (or any other strong power) would be a 42-centimetre gun pointed at India.’ 16 This required Britain to Alfred T. Mahan, ‘The Persian Gulf and international relations’, National Review (September) (1902) 27-45. Mahan took a close interest in naval history and geopolitics, and while at the US Naval War College he published The influence of sea power upon history 1660-1783 (1890). 16 Morris Jastow The War and the Bagdad Railway: the story of Asia Minor and its relation to the present conflict (London and Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1917; second edition 1918) p. 97. 15 10 confront the Ottoman Empire not only on land and sea – as it did again and again after Turkish forces openly joined the Central Powers in October 1914 – but also in the court of public opinion. Since the Crimean War there had been a popular conviction both at home and abroad that a ‘Near East’ – a locution widely used in archaeology – defined lands that were a natural part of the Ottoman Empire. The British government artfully appropriated the new ‘Middle East’ to redefine them as lands that had been oppressed, enfeebled and impoverished by centuries of Ottoman despotism and misrule: ‘a landscape haunted by gallows, disease and famine.’ 17 The language was consistent with the image of the Ottoman Empire as a ‘sick man’ that had been steadily gaining ground since the 1860s (especially as the Ottoman Empire lost ground), and it lives on in the pathological and even bio-political imaginative geography of the Middle East as a place of dis-ease. Indeed, Sir Mark Sykes, the policy adviser who masterminded the publicity campaign for Lloyd George, subsequently called the military remedy ‘cutting out the cancer’. This startling affirmation of the restorative powers of conquest and colonialism reappears in the twenty-first century metaphors of oncology and chemotherapy that have been deployed during the US-led invasions of Afghanistan in 2001 and Iraq in 2003, in which insurgency is described as a cancer, while counterinsurgency is rendered intrinsically therapeutic: killing cells in order to save the body politic. 18 James Renton, ‘Changing languages of empire and the Orient: Britain and the invention of the Middle East, 1917-1918’, Historical Journal 50 (2007) 645-667: 649; see also Roger Adelson, London and the invention of the Middle East: money, power and war, 1902-1922 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995). 18 Gregory, ‘Seeing Red’. 17 11 The First World War offered much less clinical consolation, but these imaginative geographies encouraged the conceit that its eastern theatre was the stage for a war of liberation. By the summer of 1916, as James Renton shows with admirable clarity, the new concept of the ‘Middle East’ signified ‘a revived nationalized landscape between East and West, that was to be free from Ottoman despotism and would achieve redemption under Allied protection’. 19 In March 1917 Baghdad fell to British troops – most of them, significantly, dispatched from India 20 – and Sykes drafted a proclamation for Lt General Stanley Maude to read to the inhabitants of the city: ‘Our military operations have as their object the defeat of the enemy, and the driving of him from these territories. In order to complete this task, I am charged with absolute and supreme control of all regions in which British troops operate; but our armies do not come into your cities and lands as conquerors or enemies, but as liberators.’ One can hear echoes of this too in the rhetoric of ‘Operation Iraqi Freedom’. The proclamation also reaffirmed the importance of commercial interests – ‘for 200 years have the merchants of Baghdad and Great Britain traded together in mutual profit and friendship’– that were not altogether foreign to the later American mission. A recurring emphasis throughout the British campaign and the attendant diplomatic negotiations was the renaissance of Arab nations that had been suppressed by Ottoman domination. Britain’s commitment to their revival was supposed to be evidenced by its support for Renton, ‘Changing languages’, p. 653. During the First World War British political and military interests in Egypt, Palestine, Western Arabia and ultimately Syria were controlled through Cairo, while those in Persia, the Gulf, Mesopotamia and Eastern Arabia were controlled through New Delhi. 19 20 12 the Arab Revolt against the Turks in 1916-18, but the secret agreement that Sykes had concluded on behalf of Britain with French diplomat François– George Picot in 1916, dividing the post-Ottoman world into separate British and French spheres of control, showed that the appeal to self-determination was an illusion. Nationalism was used as a justification for imperialism, and Allied ‘protection’ meant, at best, Allied tutelage. 21 *** The region was re-defined after the First World War with the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the attempt by the Great Powers to divide most of the spoils between them, but it retained its strategic inflection and gained geo-economic significance through the importance of oil (at first as the basis for naval supremacy). 22 The principal European powers drew new lines on the map to create new (client) states, replacing one set of colonial relations with others, and in 1921 Churchill created a Middle East Department in the Colonial Office whose area of responsibility was Iraq, Palestine, Transjordan and Aden. The new colonial geography continued to be enforced through military violence but this now assumed new forms as the Middle East became a central laboratory, along with others in North and East Africa, in which, as Khalidi observes, ‘the military high-technology of the post-World War One era was first tried out, and where the textbook on the aerial 21 For a detailed account of the intrigue surrounding the Sykes-Picot agreement and its devastating consequences over the next thirty years, see James Barr, A Line in the Sand: Britain, France and the struggle for the mastery of the Middle East (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011). 22 Oil was discovered in Persia in 1908, in Mesopotamia in 1927 and in Saudi Arabia in 1938. For an illuminating revision of the standard history of oil in the Middle East, see Timothy Mitchell, Carbon democracy: political power in the age of oil (London: Verso, 2011) Ch. 2. 13 bombardment of civilians was written.’ 23 British colonial dominion became uniquely dependent on ‘air control’ or ‘air policing’, and in the 1920s and 30s its squadrons conducted repeated bombing missions along India’s North-West Frontier with Afghanistan, in Mesopotamia and in Palestine. 24 These campaigns depended on three assertions. The first was that they were cost-effective: that it would be extraordinarily difficult to assert colonial authority over these vast spaces by ground forces, and the trackless deserts of the Middle East were supposedly ideal for air control. 25 The second was that colonial populations were peculiarly susceptible to the power of bombing from the air, because they had no comprehension of its technical basis and so viewed it as divine retribution. The third was that air strikes were more humane than conventional measures involving troops and artillery, and the Royal Air Force rejected the charge that in the Middle East it was conducting ‘bloody and remorseless attacks against defenceless natives’ (though it failed to explain how they could have defended themselves). 26 Rashid Khalidi, Resurrecting empire: Western footprints and America’s perilous path in the Middle East (Boston: Beacon Press, 2004) p. 27. 24 David Omissi, Air power and colonial control: the Royal Air Force 1919-1939 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990). 25 T.E. Lawrence – ‘Lawrence of Arabia’– had been drawn to the open spaces of the sky as well as those of the desert, and long before he resigned his Army commission and reenlisted in the Royal Air Force as Aircraftsman Ross, he had felt a close affinity between them. Patrick Deer suggests that in Lawrence’s personal mythology ‘air control in the Middle East offered a redemptive postscript to his role in the Arab Revolt of 1916-18’: see ‘From Lawrence of Arabia to Aircraftsman Ross: air power’s imperial romance’, in his Culture in camouflage: war, empire and modern British literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008) pp. 64-73. 26 Priya Satia, ‘The defense of inhumanity: air control and the British idea of Arabia’, American historical review 111 (2006) 16-51; Priya Satia, Spies in Arabia: the Great War and the cultural foundations of Britain’s covert empire in the Middle East (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008) pp. 242, 249-51, 256-8; Toby Dodge, ‘The imposition of order: social perception and the “despotic” power of airplanes’, in his Inventing Iraq: the 23 14 To consolidate its operations the Royal Air Force established a Middle East Command in 1932, which was originally confined to Egypt, Sudan and Kenya and enlarged in 1938 to include squadrons in Palestine, Transjordan, Iraq, Aden and Malta. The British Army established its own Middle East Command in 1939, and naval forces in the eastern Mediterranean were integrated into the high command headquartered in Cairo. The geographical area assigned to these commands was fluid, changing with the locus of combat, but a crucial responsibility was to protect the Suez Canal and the oil fields in the region. In 1941 Britain took further measures to manage its military supply chain by establishing the Middle East Supply Centre in Cairo – its responsibilities grew rapidly and it became an Anglo-American operation the next year – and when Churchill appointed a Minister of State in the Middle East and sent him to Cairo in the summer it was clear that Britain’s ‘Middle East’ – the possessive is essential – had assumed a newly coherent form, no longer an ancillary to British India or a remnant of the Ottoman Empire, and that its centre of gravity had shifted to Cairo. 27 *** This re-mapping (and its re-orientation) was confirmed after the Second World War, but the cartographers were now American. Soon after the war ended the region was plunged back into conflict by the enforced failure of nation building and a history denied (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003) pp. 131-156. 27 Robert Vitalis and Steven Heydemann, ‘War, Keynesianism and colonialism’, in Steven Heydemann (ed), War, institutions and social change in the Middle East (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000); Roger Adelson, ‘British and US use and misuse of the term “Middle East”’, in Bonine, Amanat and Gasper, Is there a Middle East? pp. 36-55: 46. 15 partition of Palestine, the foundation of the state of Israel in 1948 and the violent dispossession of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians. By then, Britain’s star was fading fast, a fact dramatically confirmed by the Suez Crisis of 1956. American interest in the region had intensified, both overtly and covertly, in response to the expanding Soviet sphere of influence, and it was during the Cold War that the idea of a ‘Middle East’ was consolidated in the United States. 28 The region was mapped into what President Carter’s National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski identified in 1978 as an ‘arc of crisis’ – though US complicity in sowing these crises was rarely mentioned by its politicians – and this imaginative geography, in seemingly endless variations on a single theme, spanned a series of wars between Arab states and Israel, the Israeli occupation of Gaza and the West Bank after 1967, the unresolved Palestinian question and the Intifada, the civil war in Lebanon (1975-90), the Iranian Revolution in 1979 and the Iraq-Iran war (1980-88). In 1980 the United States confirmed its geo-graphing of the Middle East as economically pivotal and politically unstable by establishing a Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force in order to respond ‘to contingencies threatening US vital interests’ across East Africa, the Arabian peninsula, Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan. If this realized the ‘mobility’ that Mahan had deemed essential for securing the Middle East it did so radically new form: no longer confined to sea power, this was a ‘full spectrum’ capability that integrated air, sea and ground forces. In 1983 the Joint Task Force was transformed into a unified combatant command, US Central Command (CENTCOM), explicitly charged with covering ‘the “central” area of the globe between the European and Pacific Commands’. In significant part 28 Khalidi, Sowing crisis; see also Zachary Lochman, Contending visions of the Middle East (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004). 16 CENTCOM retraced Britain’s wartime Middle East Command, but middle had yielded to centre: not only cartographically centred but also strategically central. CENTCOM’s Area of Responsibility has varied but it has never included Israel or occupied Palestine, which remain the preserve of US European Command or EUROCOM. This is, in part, the product of what John Morrissey calls its ‘perennial focus on the geopolitics of energy’, but it also has something to do with a modern Orientalism that cleaves Israel from the Arab World. This strategic geography underscores the intimate liaison between military power and cultural formation, and between geopolitics and economics, in contemporary constructions of the Middle East. 29 This has become even clearer in the turbulent wake of 9/11. The response to the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington dramatically increased the role of CENTCOM in the US scripting of the Middle East, but this deadly gavotte – in which violence unleashes more violence 30 – has also reactivated classic Orientalisms in ever more lurid forms. At the limit, the Middle East has been reduced to what Fareed Zakaria described in an angry essay in Newsweek in October 2001 as ‘the land of suicide bombers, flagburners and fiery mullahs.’ In a single, dreadful phrase the various, vibrant cultures of the region were fixed and frozen into one diabolical landscape. Manoeuvres like Zakaria’s work to set the Middle East apart – as a wholly John Morrissey, ‘The geo-economic pivot of the Global War on Terror: US Central Command and the war in Iraq’, in David Ryan and Patrick Kiely (eds), America and Iraq: policy-making, intervention and regional politics (New York: Routledge, 2008) pp. 103-24: 110. 30 As I have argued elsewhere, the spiral of violence did not begin on 9/11: see Derek Gregory, The colonial present: Afghanistan, Palestine, Iraq (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004). 29 17 exceptional space – and to privilege the United States as what Zakaria called, equally absurdly, ‘the universal nation’. 31 *** Ten years later, it is tempting to say that American (and European) commentators have finally acknowledged that the people of the Middle East can write their own history – and their own future. Said’s critique of Orientalism borrowed a telling phrase from Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire as its epigraph: ‘They cannot represent themselves, they must be represented.’ This was the authorising conceit not only of Orientalism but also of ideas of the ‘Middle East’. And yet, watching the Arab Spring as it unfolded across North Africa and into Egypt and the Gulf through 2011, Time trumpeted the rise of ‘The New Middle East’. One of its editors admitted he was surprised: ‘I didn’t think the [Arab] kids had it in them,’ he wrote: ‘They had plenty of cause to rebel but seemed unwilling or unable to do it.’ But the magazine’s political columnist ended on an upbeat note: seeing ‘support of American values in the region’ – by which he meant ‘freedom, democracy’ – Joe Klein urged his Arab and American readers to turn their eyes from US military or economic intervention to ‘the power of example’. ‘The ideal of the Tahrir Square masses, the dream of the Tunisian fruit seller, the goal of the brave Syrians facing Assad’s army in the streets, was to have the same freedoms that we have.’ 32 Klein’s self-congratulatory coda shows that, even now, the imperial cartographers still stand outside their map and assert the privilege of their own perspective. Introducing the State Department’s annual report Fareed Zakaria, ‘The politics of rage: why do they hate us?’ Newsweek, 15 October 2001; ‘Our way’, New Yorker, October 14-21 (2002). 32 Bobby Ghosh, ‘The young and the restless’, and Joe Klein, ‘What America can do’, in The New Middle East (Time Special, 2012 pp. 12-17, 110-1. 31 18 on human rights in May 2012, Hillary Clinton accepted that the Arab Spring had changed the Middle East. But she also said that the reports produced by her department made it clear to ‘governments around the world: We are watching…’ And so, in response, I want to end with Said’s wonderfully ringing cry in After the last sky. It was addressed to his Palestinian compatriots, but it can now surely be extended: ‘I would like to think we are not just the people seen or looked at in these photographs. We are also looking at our observers. We Palestinians sometimes forget that – as in country after country, the surveillance, confinement and study of Palestinians is part of the process of reducing our status and preventing our national fulfillment except as the Other who is opposite and unequal, always on the defensive – we too are looking, we too are scrutinizing, assessing, judging. We are more than someone’s object. We do more than stand passively in front of whoever, for whatever reason, has wanted to look at us.’ 33 As we look at the artworks in this exhibition, I hope we will recall these words: for the very best art requires us to look not only at its subject but also into ourselves. And in doing so, we might reflect on the multiple ways in which Europe and America have imposed their own ideas and interests through the artful construction of a ‘Middle East’ that, both imaginatively 33 Edward Said (with Jean Mohr), After the last sky: Palestinian lives (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999; first edition, New York: Pantheon, 1986) p. 166. 19 and materially, has done extraordinary violence to other people and other places. 20