File

advertisement

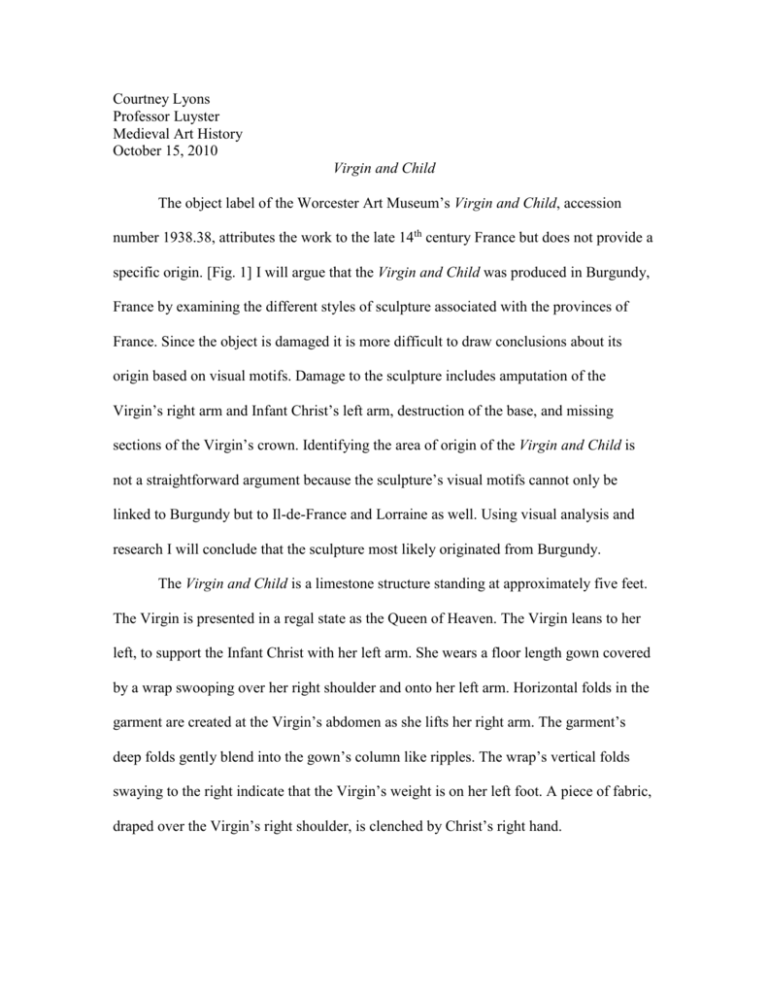

Courtney Lyons Professor Luyster Medieval Art History October 15, 2010 Virgin and Child The object label of the Worcester Art Museum’s Virgin and Child, accession number 1938.38, attributes the work to the late 14th century France but does not provide a specific origin. [Fig. 1] I will argue that the Virgin and Child was produced in Burgundy, France by examining the different styles of sculpture associated with the provinces of France. Since the object is damaged it is more difficult to draw conclusions about its origin based on visual motifs. Damage to the sculpture includes amputation of the Virgin’s right arm and Infant Christ’s left arm, destruction of the base, and missing sections of the Virgin’s crown. Identifying the area of origin of the Virgin and Child is not a straightforward argument because the sculpture’s visual motifs cannot only be linked to Burgundy but to Il-de-France and Lorraine as well. Using visual analysis and research I will conclude that the sculpture most likely originated from Burgundy. The Virgin and Child is a limestone structure standing at approximately five feet. The Virgin is presented in a regal state as the Queen of Heaven. The Virgin leans to her left, to support the Infant Christ with her left arm. She wears a floor length gown covered by a wrap swooping over her right shoulder and onto her left arm. Horizontal folds in the garment are created at the Virgin’s abdomen as she lifts her right arm. The garment’s deep folds gently blend into the gown’s column like ripples. The wrap’s vertical folds swaying to the right indicate that the Virgin’s weight is on her left foot. A piece of fabric, draped over the Virgin’s right shoulder, is clenched by Christ’s right hand. Lyons 2 Left. Fig 1. Virgin and Child. Worcester Art Museum. 1938.83. Right. Fig 2. Virgin and Child. Worcester Art Museum. 1938.83. Virgin’s left arm and side of Infant Christ. Lyons 3 A half-clothed Christ Child sits perched on the Virgin’s left side. A small garment cover’s Christ’s lower half as well as his left shoulder. Unlike the free flowing robes of the Virgin, Christ’s covering has short distinct creases. The Infant Christ sits with his legs crossed creating a peak in the drapery. The Virgin’s vertical hand covers the majority of the Infant Christ’s legs. The body of the Christ Child resembles the common features of a young child. Christ sits nearly upright, leaning forward just enough to create a crease between his chest and abdomen. His stomach is rounded and protrudes forward like that of a young child. While now faded, small dark ovals on Christ’s chest represent his nipples. Deep circular incisions mark Christ’s wrist and elbow, creating a sense of roundness. His right arm extends downward allowing his fingers to clasp onto the fabric around the Virgin’s shoulder. Christ pulls the garment toward his abdomen effortlessly, indicating his ability to support his own weight. Christ’s left shoulder and bicep are covered by the same garment also wrapped around his waist. Christ’s left hand and forearm are missing. The Christ Child bears a rounded head marked by adult like facial features. Christ’s head sits in the center of his shoulders aligned with the direction of his legs. Christ has distinctly thick hair, depicted in the shape of a flattened snail pattern. Abnormally large ears pierce through Christ’s hair. The semi-circular shape of the ears emphasizes his lean facial structure. Christ’s eyes are represented by two large almonds slanted slightly downwards. His eyelids are depicted through small thin lines mirroring the shape of the upper eye. To accentuate the beginning of the top if his nose the inner sections of Christ’s eyes are set deeper in the limestone, than the outer parts of the eye. In the middle of Christ’s head lies a prominent nose. The nose’s sharp slanted bridge and Lyons 4 flat tip are more reminiscent of the features of an adult man than of an Infant. Thin marks from the edge of His nostrils connect to the ends of his mouth. Christ’s lips are pierced together and angled upwards. Shaped like a crescent moon, the upper lip overlaps with the protruding bottom lip. The Infant Christ carries a small smirk distinct from the Virgin’s static expression. The Virgin’s head, tilted slightly to the right, sits atop a stout neck. Correctly identifying visual motifs of the Virgin is difficult because of the abrasions present on her face. The Virgin’s small rounded eyes are framed by upwards curving eyebrows. The eyebrows protrude slightly thereby emphasizing that the eyes are set deeper within the limestone. The Virgin’s eyes are rounder and smaller than Christ’s. A thin deep incision below her eyes alludes to her age. The Virgin’s eyes are set between a long rounded nose. The nose slants to the right as a result of the Virgin’s tilted head. The Virgin bears tightly closed lips that project slightly forward. Compositionally, her lips are located closely to her bulbous chin. The Virgin’s right arm is absent beyond her elbow. It is more difficult to determine its region of origin since important visual features of the sculpture are missing or damaged. Provinces in France are associated with specific ornamentation or motifs that they incorporated into their artworks. Thus if the Virgin and Child has certain visual attributes that are typically associated with one region, we can conclude that the object most likely derived from or was influenced by that area.1 After examining the regional sculptural styles of works depicting the Virgin and Child, I concluded the WAM most likely originated from Il-de-France, Lorraine, or Burgundy. William H. Forsyth. “The Virgin and Child in French Fourteenth Century Sculpture A Method of Classification” The Art Bulletin 39, no.3 pp. 171-173 1 Lyons 5 This examination was conducted by visually comparing the Virgin and Child to similar works originating from France between the 13th and 15th centuries. Ile-de-France was a leading commercial center and producer of the arts.2 Sculptures made in Il-de-France influenced provincial art partly because artists were constantly moving in and out of the area. Sculptures produced in regions close to Il-deFrance closely resemble that sculptural style and share similar visual motifs.3 Since the Virgin and Child is missing key features it is more difficult to determine whether it more closely resembles works from Il-de-France or the provinces. The Virgin and Child is presented in a regal state like that of many of the sculptures stemming from Il-de-France. This style reflects the court art that was produced in Paris. 4The Virgin is presented as a woman of the court since she is wearing a jeweled crown.5 However, the virgin carries physical features that are unlike that of sculptures from Il-de-France. Unlike the Madonna sculptures of Il-de-France, the Virgin is not bearing a smirk but wears a static expression. However, the Christ Child has a slight smirk as his lips protrude forward. Furthermore, the tin body type that is usually associated with sculpture from Ile-de-France does not describe the Virgin and Child. Sculptures of the Virgin and Child originating from Burgundy and Lorraine are stylistically similar since Burgundy art pieces influenced work in Lorraine6. It is important to explore these similarities to ultimately determine their distinctions that make Brigitte Baccaini. “Recent Periurban Growth in the Ile-de-France: Forms and Causes.” Population: An English Selection, Vol. 10, no 2 (1998), p. 349. 3 William H. Forsyth. “The Virgin and Child in French Fourteenth Century Sculpture A Method of Classification” The Art Bulletin 39, no.3 pp. 171-173 4 Andre Chastel. 1994. French Art Prehistory to the Middle Ages.a New York: Flammarion. p. 282 5 Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters. "The Cult of the Virgin Mary in the Middle Ages". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. 6 William H. Forsyth. “The Virgin and Child in French Fourteenth Century Sculpture A Method of Classification” The Art Bulletin 39, no.3 pp. 176 2 Lyons 6 Burgundy and Lorraine sculpture different from each other. Most significantly, Lorraine and Burgundy sculptures are often constructed from a common medium, limestone. A Virgin and Child sculpture stemming from Lorraine is usually identified by three features: the Virgin’s crown, girdle, and the rose held by the Christ Child. The crown worn by the Virgin is more basic than the extravagant jewled crown seen in sculptures form Il-de-France. Often the crown is a wreath of roses that can symbolize the mystic marriage. This vegetal design can be seen throughout the piece including on the virgin’s girdle.7 While the girdle is typically seen on the Virgin from Il-de-France it does not have the same vegetal motif.8 The Christ Child is usually be depicted holding a rose in his left hand and sometimes the Virgin will be clasping a rose or a bouquet of Irises. If the Virgin is not holding a rose then she will most likely be grasping a scepter. Stylistically, the gown of the Virgin tends to be simplistic in design.9 The Virgin is often wearing an jeweled or decorated mantle. A Virgin from Lorraine can typically be identified by her short veil that grazes her shoulders. 10 The extent to which the Virgin and Christ interact with each other varies between sculptures.11 Based on an understanding of common characteristics of Lorraine sculptures depicting the Virgin and Child it can be determined that the WAM object most likely did not originate from this region. The Virgin and Child does not portray the vegetal rose motif that is common with Lorraine works that depict the Holy Family. While sections of 7 William H Forsyth. “Medieval Statues of the Virgin in Lorraine Related in Type to the Saint-Die Virgin.” Metropolitan Museum Studies 5, no. 2 (1936): p. 235. 8 William H Forsyth. “The Virgin and Child in French Fourteenth Century Sculpture A Method of Classification.” The Art Bulletin 39, no. 3 (1957): pp.171-182 9 William H Forsyth. “A Fifteenth-Century Virgin and Child Attributed to Claux de Werve.” Metropolitian Musuem Jouranl, Vol 21 (1986): 59. 10 William H Forsyth. “Medieval Statues of the Virgin in Lorraine Related in Type to the Saint-Die Virgin.” Metropolitan Museum Studies 5, no. 2 (1936): pp.236-238 11 James D Breckenridge. “Et Prima Vidit”: The Iconography of the Appearance of Christ to His Mother.” The Art Bulletin 39, no. 1 (1957): 9-32 Lyons 7 the Virgin’s crown are missing, hindering the formal analysis, it can be determined that it is more ornate than a crown that would typically be displayed on a Virgin from Lorraine. The Virgin and Child resembles a description of a Lorraine sculpture primarily based upon clothing. The Virgin and Child wears a simplistic gown that falls into long folds and she wears an embellished mantle around her neck. However, it should be noted that sometimes Virgin sculptures from Ile-de-France are depicted with shorter veils.12 A significant piece of evidence against the claim that the Virgin stems from Lorraine is the absence of a girdle since most sculptures from Loraine have this attribute. Without a girdle, regardless it ornamentation motif, the Virgin appears wider. This wideness is a very popular theme associated with Burgundy sculptures.13 Drawing parallels between the Virgin and Child and Lorraine sculpture can be difficult because the work is damaged. Since the Virgin is missing her right hand the Christ Child his left hand it is impossible to know what object they were holding. Without knowing the identity of the objects that the figures held, it is difficult to determine the origin of the sculptures. Identifying these objects would make determining the origin of the sculpture easier.14 It is unlikely that the Christ Child was grasping a rose since the vegetal theme associated with Lorraine is not present anywhere else on the sculpture. It is possible that the Virgin was holding a scepter in her right hand; however since scepters are often a result of restorations, the presence of that object can not entirely determine the origin of a work. 15 12 Paul Williamson. 1987. Medieval Sculpture and Works of Art. London: Sotheby’s Publications. pp. 118120 13 William H Forsyth. “The Virgin and Child in French Fourteenth Century Sculpture A Method of Classification.” The Art Bulletin 39, no. 3 (1957): 171-182 14 Ibid 15 Ibid. pp. 173 Lyons 8 The sculptures depicting the Virgin and Child originating from Burgundy reflect a distinct regional style of that area. Once the attributes and characteristics of provincial sculpture have been defined, the WAM’s Virgin and Child can be compared to Burgundy sculpture. A Virgin and Child stemming from Burgundy can typically be identified by her bloated cheeks and double chin. 16 Mary appears as a heavier and wider figure because of the column-like folds in her gown. Since many sculptures of the Virgin and Child from Burgundy were polychrome and gilded, it is important to determine if the Virgin and Child was once painted.17 Currently the sculpture is a muted limestone color. However, certain areas of the sculpture appear significantly darker in color than other regions of the piece [Fig 2]. This observation has remained consistent after visiting the sculpture several times over a period of two months. As such it cannot be argued that this difference in coloring is a result of the sculpture undergoing cleaning at the museum. Possibly the sculpture was painted and the colors have faded differently because of their chemical makeup. The small faded black pupils of the Virgin and Child are the strongest piece of evidence supporting the claim that the piece was once painted [Fig. 3, 4]. Since both figures have colored pupils it is possible that at one point they were entirely painted, such as Fig 4. The pupils of the Virgin are much darker than the pupils of the Infant Christ. The difference in the degree of color of their pupils could be for a variety of reasons, which could only really be determined if the background of the piece was known. Forsyth, William H. “A Medieval Statue of the Virgin and Child.” The Metropolitian Museum of Art Bulletin 3, no. 3 (1944): p. 85 16 Lyons 9 Fig 3. Pupils of the Virgin. Virgin and Child. Worcester Art Museum. 1938.83 Fig 4. Pupils of the Infant Christ. Virgin and Child. Worcester Art Museum. 1938.83 Lyons 10 To demonstrate that the Virgin and Child physically resemble sculptures typically associated with Burgundy, I will compare the work to two pieces from Burgundy. The first object also titled Virgin and Child, depicts a seated Madonna. Since both the WAM piece and Fig 4 share the same title, the WAM object will be referred to as the “standing Virgin” and the latter will be called the “seated Virgin”. Any visual attributes that the figures share that are attributed to Burgundy sculptures will help support the argument that the Virgin and Child originated from Burgundy. The seated Virgin, created in 1420 in Burgundy, depicts the Virgin holding the Infant Christ gesturing toward a Bible. The sculpture is 135.5 x 104.5 x 68.6 cm in dimension and is a polychrome limestone with gilding. Although at first glance the Burgundy sculpture appears drastically different to the WAM’s Virgin and Child, both sculptures actually share similar attributes. Defining common visual attributes between these two objects is imperative to arguing that the Virgin and Child originated from Burgundy. The more common visual attributes that the standing Virgin shares with the seated Virgin, it is more likely the work stemmed from Burgundy. The Virgins share a similar facial structure. The seated Virgin has a particularly wider face, a trait common to Burgundy sculptures.18 The angle at which the Virgin’s head is tilted, down to her right, emphasizes the wideness of her forehead. The Virgin has a very rounded chin that appears fatter because her face is pushed inward toward her neck to allow her to look at the Infant Christ. The WAM’s Virgin and Child like the seated Virgin has an octagonal shaped head and a double chin. William H. Forsyth. “The Virgin and Child in French Fourteenth Century Sculpture A Method of Classification” The Art Bulletin 39, no.3 p. 175 18 Lyons 11 Fig 3. Virgin and Child. 1420. Made in Burgundy, Poligny. Limestone, polychromy, gilding. 135.5 x 104.5 x 68.6 cm Artstor Fig 4. Virgin and Child. 1420. Made in Burgundy, Poligny. Limestone, polychromy, gilding. 135.5 x 104.5 x 68.6 cm Artstor Lyons 12 The seated and standing Virgins have similar hairstyles. The standing Virgin’s hair, distinctly patterned by concentric parabolas, is hidden beneath her veil. Her hair creates a streamlined hairline thereby emphasizing her oval face. The Virgin’s hair blends into her clothing. The hair of the seated Virgin is much more naturalistic because of its soft brown color and fullness. While the seated Virgin’s hair maintains a unique curving form like the standing Virgin the hair also has depth. The hair of the standing virgin appears almost unrealistic and one dimensional because the observer can only see the curly hair immediately surrounding her face. More of the seated Virgin’s hair is revealed to the viewer since her veil starts closer to the midpoint of the top her head Both of the Christ Childs share a similar patterned hair. Tight circular uplifted limestone represents the hair of the both figures. Their hairline is also the same in that is recesses on both sides and is pointed at the center. The hair of the infant Christ on the seated virgin is a much more variable in line and less controlled than that of the hair of the standing Christ and child. Visually the enthroned and standing Virgin and Child sculptures appear very different from each other. The WAM sculpture appears as a woman of the court whereas the seated virgin does not because of the absence of the crown or court paraphernalia. The difference in appearance could be attributed to the fact that they were created at different periods of time. The standing Virgin and Child was created before the seated Virgin and Child. The difference in visual appearance could also be accounted for by the artist or patron’s wish for the design of the sculpture. I will introduce an image of an enthroned Virgin and Child from the Sens Cathedral in Burgundy that encompasses the visual attributes of both the seated and Lyons 13 standing Virgin and Child [Fig 8]. Forsyth comments that this particular sculpture makes a connection between Il-de-France and Burgundy.19 This connection can be established by determining which of the sculpture’s visual features are associated with both Ile-deFrance and Burgundy. I incorporated to strengthen the visual link between the standing and seated Virgin. The sculpture [Fig 8] can be attributed to Il-de-France because the Virgin is portrayed in a regal state. Mary is understood by the viewer as the Queen of Heaven because of her ornate crown. She glances forward while her left hand supports the Christ Child and her right hand bears a stalk of flowers. A vegetal theme also decorates her throne. The visual motif is more closely linked to Lorraine than either Burgundy or Ile-de-France.20 The Virgin’s right hand and crown were restored. It is not evident if the restoration of these features reflects the original crown and her right hand. The enthroned Virgin wears a girdle tightly fastened below her chest, an attribute of Ilede-France works. The garment wrapping around the Virgin is very complicated in design and decoration. The folds of the grown created by her seated posture are more intricate than the tubular and column-like folds of the standing Virgin. Since the garment is very complicated in design I would suggest this sculpture was created after the WAM Virgin and Child sculptures. The enthroned Virgin does however share similarities with Burgundy sculpture, such as its wide appearance. Even though she is wearing a girdle, that synchs her waist, the garment draped over her right shoulder widens her body. This work helps to establish the understanding that sculptures from differing provinces in France can be similar stylistically and yet still be distinct. William H. Forsyth. “The Virgin and Child in French Fourteenth Century Sculpture A Method of Classification” The Art Bulletin 39, no.3 p. 175 20 William H Forsyth. “Medieval Statues of the Virgin in Lorraine Related in Type to the Saint-Die Virgin.” Metropolitan Museum Studies 5, no. 2 (1936): pp. 235-236 19 Lyons 14 Fig 8. Sens Cathedral. The Virgin and Child from the Worcester Art Museum most likely originated from Burgundy France. Determining the origin of the sculpture is important since its composition reflects the views of the patron. Determining the origin of the sculpture is difficult because during the Romanesque and gothic periods many sculptures depicting the Virgin and Child were produced as a result of the growing popularity of the cult of the Virgin in France.21 Based upon visual analysis and an understanding of the schemas of the regional sculptural styles of provinces in France the Virgin and Child from the 21 Joseph Breck. “A Marble Statue of the Virgin.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 20, no. 2 (1925): 39 Lyons 15 Worcester Art Museum most likely originated from Burgundy. I compared the Virgin and Child to other sculptures from Burgundy to determine their common attributes.