View/Open

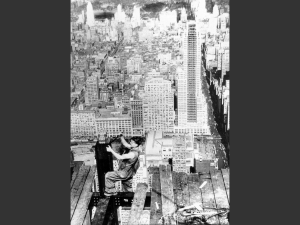

advertisement

Modernity and modernities. Challenges for the historiography of modern architecture Hilde Heynen 1. The concept of modernity In my book ‘Architecture and Modernity. A Critique’ I related the history of the Modern Movement in architecture to the conceptualization of modernity by authors such as Marshall Berman, Jürgen Habermas and Jean Baudrillard. According to these authors, modernity is what gives the present the specific quality that makes it different from the past, and which points the way towards the future. Modernity is often described as a break with tradition, and as typifying everything that stands for the new, the innovative and the daring. Since the 18th century, the century of the Enlightenment in Europe, modernity was seen as bound up with critical reason – the idea that there is no ulterior authority, that men’s capacity to critically question everything takes precedence over any form of Revelation. Modernity hence is constantly in conflict with tradition and it embraces the struggle for change. In the 19th century modernization gained ground in the economic and political fields. With industrialization, political upheavals and increasing urbanization modernity became far more than just an intellectual concept. In the urban environment, in changing living conditions and in everyday reality, the break with the established values and certainties of the tradition could be both seen and felt. The modern became visible on very many different levels. In this respect Marshall Berman insists that a distinction should be drawn between modernization (the socio-economic process), modernity (the condition of life) and modernism (the body of tendencies and movements that embrace modernity).i Modernity hence mediates between a process of socio-economic development known as modernization and subjective responses to it in the form of modernist discourses and movements. One can further draw a distinction between different concepts of modernity – programmatic and transitory. The advocates of a programmatic concept interpret modernity as being first and foremost a project, a project of progress and emancipation. They emphasize the liberating potential that is inherent in modernity. A programmatic concept views modernity primarily from the perspective of the new, of that which distinguishes the present age from the one that preceded it. A typical advocate of this concept is Jürgen Habermas. He formulates what he calls the `incomplete project' of modernity as follows: "The project of modernity formulated in the 18th century by the philosophers of the Enlightenment consisted in their efforts to develop objective science, universal morality and law, and autonomous art according to their inner logic. At the same time, this project intended to release the objective potentials of each of these domains from their esoteric forms. The Enlightenment philosophers wanted to utilize this accumulation of specialized culture for the enrichment of everyday life - that is to say, for the rational organization of everyday social life."ii In this programmatic approach two elements can be distinguished. On the one hand, according to Habermas - with specific reference to Max Weber - modernity is characterized by an irreversible emergence of autonomy in the fields of science, art and morality, which must then be developed `according to their inner logic'. On the other hand, however, modernity is also seen as a project: the final goal of the development of these various autonomous domains lies in their relevance for practice, their potential use `for the rational organization of everyday social life'. In Habermas' view great emphasis is placed on the idea of the present giving form to the future, i.e. on the programmatic side of modernity. In contrast to this programmatic concept the transitory view stresses rather the transient or momentary. According to Jean Baudrillard, the programmatic is gradually giving way for the transitory, in which modernity is no longer a project but rather a fashion: “Modernity provokes on all levels an aesthetics of rupture, of individual creativity and of innovation which is everywhere marked by the sociological phenomenon of the avant-garde (...) and by the increasingly more outspoken destruction of traditional forms (...) Modernity is radicalized into momentaneous change, into a continuous traveling and thus its meaning is changing. It gradually loses each substantial value, each ethical and philosophical ideology of progress which sustained it at the outset and it is becoming an aesthetics of change for the sake of change (...) In the end, modernity purely and simply coincides with fashion, which at the same time means the end of modernity.”iii Modernity, according to Baudrillard, establishes change and crisis as values, but these values increasingly lose their immediate relation with any progressive perspective. The result of this loss is that modernity begins to run away with itself and sets the scene for its own downfall. Thinking the transitory concept of modernity through to its conclusions can lead to the proclamation of the end of modernity and, taking it one step further, to the postulation of a post-modern condition. Generally, one can state, at least as far as the architectural discourse is concerned, that modernism in architecture is mostly based on a programmatic understanding of modernity, whereas postmodernism rather embraces a transitory concept of the same. For Marshall Berman it is precisely the relationship between all these divergent aspects that makes modernity so fascinating. For the individual the experience of modernity is characterized by a combination of programmatic and transitory elements, by an oscillation between the struggle for personal development and the nostalgia for what is irretrievably lost: "To be modern is to find ourselves in an environment that promises us adventure, power, joy, growth, transformation of ourselves and the world - and at the same time, that threatens to destroy everything we have, everything we know, everything we are."iv The character of modernity is indeed ambivalent and contradictory. Modernity provokes changes on all levels, and destroys traditional forms, destroys the world as we knew it. That means that for most everyone involved with modernity, there is on the one hand joy in the change, in the process of improvement, but on the other hand, at the same time, regret because many things of the past have been destroyed. 2. Multiple modernities Whereas Berman and the other authors discussed thus far treated modernity as a singular phenomenon, since the 1980s the idea has emerged that modernity can take on different forms and that it is not the same everywhere. As Duangfang Lu states, in a recent contribution to ‘The Sage Handbook of Architectural Theory’: “To think the modern is to think the present, which is necessarily caught in the ever-shifting social, political, and cultural cross-currents. For many decades, modernization was depicted in social sciences as a broad series of processes of industrialization, rationalization, urbanization, and other social changes through which modern societies arose. The concept has been heavily criticized for its Eurocentric assumptions in recent years. It assumes, for example, that only Western society is truly modern and that all societies are heading for the same destination. With the epistemological break triangulated by the poststructuralist, postmodern, and postcolonial theory, the dominance of this biased progressive historicism and its associated binaries (modern/traditional, self/other, center/periphery, etc.) are challenged. The questions about modernity, understood as modes of experiencing and questioning the present, are re-thought.”v The understanding that modernity might have different manifestations was already evoked by Shmuel N. Eisenstadt, in arguing that Eastern Europe under communism went through its own form of modernization, and was thus facing other challenges. According to him the breakdown of communist regimes in 1989 had to do with the contradictions within their implementation of modernity. These contradictions were rooted in the nature of the vision that combined the basic premises of modernity, together with far-reaching strong totalitarian orientations and policies. He thus spoke about multiple modernities, stating that “The actual developments in modernizing societies have refuted the homogenizing and hegemonic assumptions of this Western program of modernity.”vi Also postcolonial theorists argue that the Western / European model of modernity was in fact just one among many – not the leading beacon that other countries were following, but rather a specific historical configurations of forces that led to a specific outcome, whereas in other parts of the world other configurations necessarily led to other outcomes – no less modern, but modern in another fashion. Dipesh Chakrabarty coined the phrase ‘Provincializing Europe’ – the title of one of his books – to point to the fact that the history of European social relations is not necessary a model that is being emulated everywhere else.vii Hence it doesn’t make a lot of sense to see e.g. Karl Marx as an authority for eternity, because he happened to understand the logics of 19th century political economy in Europe. For sure, he claims, Marx remains a major philosopher and economist, one can still be inspired by his worldview and his work, but it would be wrong to think that ‘Das Kapital’ offers a key for interpreting each and every crisis wherever in the world. ‘Provincializing Europe’ mainly addresses his fellow Indian intellectuals, arguing that they should try much harder to understand the historical specificities and the path dependency of India’s subaltern classes. A Marxist or neo-marxist framework of interpretation can be helpful to that end, but certainly doesn’t offer the last word of wisdom to deal with these specific challenges. Marx, he argued, needs to be brought back to his real stature, which is that of an interesting intellectual whose analysis certainly carried a lot of weight when applied to 19th century Europe, but whose legacy should not be seen as the sole route to truth in understanding different trajectories of modernization in different parts of the world. Jyoty Hosagrahar, a postcolonial historian of architecture, applies these thought in her book on Delhi, which she appropriately called ‘Indigenous Modernities. Negotiating Architecture, Urbanism and Colonialism’. Her argument is that the Indian residents in Delhi formed their own form of modern dwelling, in taking some things from the colonizers while refuting others. Hence there is a modern Delhi that is not colonial Delhi, but that is not ‘traditional’ either. Hosagrahar also contributed to ‘The Sage Handbook of Architectural Theory’, where she wrote the chapter on postcolonial perspectives. According to her postcolonial perspectives have relocated discussions of modernity to ‘other’ locales and reframed modernist conversations about inclusion and exclusion. They emphasize global interconnections, and the interplay of culture and power in imagining, producing, and experiencing the built environment. She emphasizes a broad definition of postcolonialism, which includes perspectives that give voice to struggles against all types of colonialisms, and enable and empower alternative narratives and forms.viii 3. Architecture and identity If the historiography of modernism in architecture has seen quite some additions the last couple of decades, one of the more important revisions has indeed to do with postcolonial critique. This critique starts from the assumption that modernism and colonialism are in some ways intertwined – that they cannot be seen as intellectual discourses that are totally separate. For one thing, this has to do with an economic context. Take for example the Van Nelle factory, one of the famous icons of modernism. This was, in fact, a coffee, tea and tobacco factory - which means that this icon of modernity got into the world as a result of colonial expansion, colonial policy and colonial production. It cannot be denied therefore that the Van Nelle factory was part and parcel of the whole colonial condition. In the book ‘Back from Utopia’, which was edited by Hubert-Jan Henket and myself (2002), we tried to come to terms not only with the physical heritage of the Modern Movement, but also with its ideological heritage. In my own contribution I raised some issues, some questions of colonialism, which I summarized as follows: “In postcolonial theories the interconnections between the Enlightment project of modernity and the imperialist practice of colonialism have been carefully disentangled. Following the lead of Edward Said’s Orientalism, it is argued that colonial discourse was intrinsic to European selfunderstanding: it is through their conquest and their knowledge of foreign peoples and territories (two experiences which usually were intimately linked), that Europeans could position themselves as modern, as civilized, as superior, as developed and progressive vis-à-vis local populations that were none of that (…) The other, the non-European, was thus represented as the negation of everything that Europe imagined or desired to be.”ix This is, in a nutshell, the argument that Edward Said developed in his seminal book Orientalism (1978). Edward Said (1935-2003) was a Palestinian intellectual, born in Jerusalem, who became a scholar teaching at Columbia University, in New York, in the field of comparative literature. The central theme in his work is the relation between cultures. His book Orientalism starts from the assumption that the Orient is not an inert fact of nature: what we call the Orient is in the East because our point of reference is Europe. Men make their own history, he claims, they also make maps and these maps then structure our conception of reality: “Therefore as much as the West itself, the Orient is an idea that has a history and a tradition of thought, imagery and vocabulary that have given it reality and presence in, and for, the West. The two geographical entities thus support and to an extent reflect each other.”x (Said 1978, 5) In art, the term orientalism refers to a whole series of images which form a certain tradition that depicts the fantasies of Western painters about the East. Famous topics are women in the harem, women making toilets, women leading a life of luxury and laziness – or men, brave men confronting the desert alone on a horse (think of the imagery in films like David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia). Also in literature you have orientalist works, just like academic studies of the East fall under orientalism. The Orient in most of these examples captures the imagination, and evokes a very specific kind of image, with often erotic associations. Often the images suggest decadence and lascivity, a kind of looseness which is seductive, but at the same time there is an implicit moral message about the dangers of such luxury. The Orient is thus represented as full of mystery and secrets. Its people are represented as being very enigmatic, very indirect, as persons you cannot easily get to know and hence as individuals who might be unreliable. The implicit message these images and texts bring about is that the orient might be threatening, and that, therefore, it needs to be brought under control. And that message acts as a kind of alibi for the civilizing mission of the West. This kind of imagery is e.g. infamously represented in a comic strip with which we, as Belgian children, made an acquaintance with Chinese culture: Hergé’s renderings of ‘Tintin in China’. Others have made analyses of the biases and prejudices that speak from such an imagery. In the architectural world these biases are also present, albeit in a form that u often difficult to decipher. One example, deftly analyzed by Gülsüm Baydar, is the famous volume of Banister Fletcher on the world history of architecture (first edition 1896). This volume is significant for many reasons, among them the fact that it is the first attempt at writing a world history of architecture – which is in itself a daring and ambitious undertaking. Banister Fletcher thus already starts from the assumption that also other parts of the world – outside of historical Europe – might harbor valuable architecture, in itself a recognition of the value of other cultures. Nevertheless the way he represents and maps these ‘other’ architectures reveals colonialist and imperialist overtones. In his ‘tree of architecture’, the non-European architectural heritages are represented as branches that spread out from the main trunk. Thus he features Egyptian, Assyrian, Peruvian, Indian, Mexican, Chinese and Japanese architecture on the lower branches. The European styles, however, occupy the higher levels of the tree, with Greek and Roman antiquity solidly positioned on the trunk, as a fountainhead from which the rest of history springs. European traditions are thus seen as ‘historical styles’, meaning that they contain the seeds for further development. The non-European styles are ‘non-historical’, meaning they represent some eternal past (or some eternal present for that matter), and are not expected to further develop or produce any meaningful offspring in the foreseeable future. Hence the superiority of the European styles is literally inscribed into this figure. There is no way, in the imagination of Fletcher, that the non-European styles could measure up to them. Gülsüm Baydar is quite critical of Fletcher’s representation. She comments that “… Fletcher’s method tames the nonhistorical styles by submitting them to the same framework of architectural analysis as the Western ones. (…) Indian and Chinese and Renaissance and modern turn into conveniently commensurable and hence comparable categories” She blames Fletcher for committing “historiographical violence…”, since he doesn’t recognize that his ‘comparative method’ overlooks all kinds of differences in historical, cultural, material, social and economic conditions, which in fact make up for quite some differences in the way architecture is conceived, built and experienced in different parts of the world.xi In ancient Chinese cultures, e.g., architecture is not counted among the fine arts, and the knowledge of how to build temples and palaces remained for a very long time in the hands of craftsmen rather than intellectuals. Hence when Liang Sicheng wrote the first history of Chinese architecture in the 1930s and 1940s, he was not building upon a body of knowledge that was easily accessible, but had to puzzle together fragments he found in many different types of texts with careful interpretations of material remains that were far and few between them. This work, one can also argue, in fact is already the result of a cultural exchange, since Liang Sicheng was academically trained in the United States, and his very understanding of architecture and architectural history was based upon this training. I don’t think however that we should call his work ‘historiographical violence’ – it rather was a rescue operation – but at the same time we should be willing to accept that architecture as a category only entered Chinese discourse and Chinese practice through the cultural exchange with the West. All this of course complicates matters when it comes to the relation between architecture and the representation of national identity. In the 19th century, when national states were being formed as a quasi-universal and even inescapable format structuring how people organize their societies, architectural history took off as an important academic discipline because it was seen as offering crucial narratives that helped anchoring the identity of these states in a clearly identifiable past. Architectural history along with preservation of monuments went a long way in helping to solidify the idea of national development and national identity, by providing a teleological story that interconnected the distant past with the present and the future.xii In that sense also Liang Sicheng’s architectural history of China certainly was helpful to create a sense of community and shared values in a country that was struggling to find its own path to the future. Whereas his architectural history on an ideological plane might have resonated best with the nationalist intentions of Chiang Kai-shek’s regime, it was to a certain extent also useful to the new communist leaders. Although Liang Sicheng lost the battle to have the walls and gates of old Beijing preserved, he was called upon to ponder about ways to develop national emblems and national building styles.xiii I want to stress however that this explicit relation between architecture and national identity is not necessarily a stable one. This is what Abidin Kusno refers to, in talking about architecture and nationalism: “Architecture is linked to nationalism when its 'semiotic' functioning organizes solidarities for a limited sovereign community as well as distinguishes the community from “outsiders.” The capacity of architecture to perform such role of subjection for the nation however relies upon not only the ways in which architecture is produced and represented, but also upon how it is imagined, received and ignored collectively. Since architecture lies within the framework set by the nation, we can also suggest the possibility of architecture transforming the framework within which its meanings are constructed. Similarly, no matter how progressive an architectural form and space may look like, it is still adaptable to the functioning of fascistic political regimes.”xiv 4. Architecture at large For me, the most interesting contributions to recent historiography of modern architecture are not necessarily to be found in the continuation of architectural histories focusing on national monuments and producing new versions of a canon of names and works. I would argue that throughout the 20th century architecture has been expanding its field, and that architectural historiography should follow suit. The Modern Movement already was to a large extent anti-monumental and anti-canonical. Its heroic protagonists in the 1920s focused on housing and on architectural as leverage to improving societal conditions. For people like Ernst May, Bruno Taut, Mart Stam or Hannes Meyer, modern architecture was first of all about improving conditions of life for the masses. What was at stake in their housing projects and new towns, was how to provide workers and families with modern amenities and modern spaces in order to enable modern lifestyles that would be emancipatory rather than oppressive. Hence they were not seeking glory for themselves by creating unique buildings that would for eternity testify of their genius, but they focusing their efforts on creating everyday environments for everyday people. That is certainly ‘expanding the field’ to me. Likewise Aldo Rossi’s understanding of architecture was bound up with his understanding of the city: architecture for him was not about sole buildings, but about buildings that made up part of an urban whole – either by standing out as ‘primary elements’ or by being part of a wider tissue. His anchoring of architecture in urban contexts that are always already historically inscribed and culturally significant again widens the scope of architecture, not limiting it to individual masterworks, but seeing it as part and parcel of the built framework of everyday life. Such an understanding of architecture has also been supported by works of sociologists such as Henri Lefebvre or Michel de Certeau, who also put emphasis on the city and on the everyday, and who figure widely in recent contributions to architectural history (see e.g. the work of Mary McLeod, Lukas Stanek, Kenny Cupers, a.o.). Another way to expand the field of architectural history and theory has been to look not only at architects as the heroes of the narratives, but also look at clients, contractors or users. Alice Friedman’s ‘Women and the Making of the Modern House’ (1998) was a major breakthrough in this respect, but also Rem Koolhaas’s recent Biennale exhibition in Venice, ‘Fundamentals’ (2014), can be seen as a contribution to this opening up. Following up on the inspiration of his 1978 volume ‘Delirious New York’, this exhibition seeks out the recent history of building elements – doors, ceilings, staircases, walls, balconies, … - in order to clarify architecture’s role in the production of modernity. In such a set-up, architecture is not at all about the major geniuses creating singular master pieces, but rather about the orchestration of all kinds of material inventions and technologies that change the way we relate to our environment. What Koolhaas and his team were doing in Venice, is significant, I would argue, for an important shift in how we see this discipline of architecture, and its related discourses of architectural history and theory. Rather than remain within its disciplinary boundaries, focusing upon masterpieces and masterminds, the most important contributions to the field are those that open up to interdisciplinary dialogues with other disciplines – history, social sciences, anthropology, geography, etc. These efforts can be seen as contributing to a better understanding of the well-known aphorism of Winston Churchill, claiming that ‘We shape our buildings, thereafter they shape us.’ For me the most important ambition of architectural theory and history has to do with this aphorism: to understand how it is that we are shaped by the buildings that we shape. In order to foster that understanding, I think we should become more conscious about how we think of the relationship between buildings (or built spaces) and social constellations. I have argued elsewhere that the relationship between spaces and social processes is viewed in the literature according to different models, three of which I see as the most basic ones.xv In the first of these three models, space is seen as a relatively neutral receptor of socio-economic or cultural processes. The second model regards spatial articulations as possible instruments in bringing about particular social processes. This model engages the built environment in a much more active way as the instigator of social or cultural change. The third model, which encompasses aspects of the first two, envisages the built environment as a stage on which social processes are played out. In the same way as the staging makes certain actions and interactions possible or impossible within a theatre play, the spatial structure of buildings, neighbourhoods and towns accommodates and frames social transformations. In conceiving of spatial arrangements as the stage on which social life unfolds, the impact of social forces on architectural and urban patterns is recognized (because the stage is seen as the result of social forces) while at the same time spatial patterns are seen as modifying and structuring social phenomena. The difference with the first model – space as receptor– is that the agency of spatial parameters in producing and reproducing social reality is more fully recognized. The difference with the second model – space as instrument – is that the theatrical metaphor is far from deterministic, and that this thought model thus allows for a better understanding of the interplay between forces of domination and forces of resistance. The third model of ‘space as stage’ thus is the model that is most promising for engaging interdisciplinary efforts to understand the relation between people and space. In the increasingly abundant literature applying postcolonial perspectives on architecture and urbanism, this approach is often adopted, yielding interesting results. Postcolonial studies of colonial planning and architecture usually bring to the fore how these interventions only rarely achieved the intended results. These studies do show, however, that the modern urban spaces that were produced by modernist planning and architecture functioned as catalysts for forms of behaviour that were definitely new and modern – if not the docile kind of ‘modern’ desired by the colonizers. Abidin Kusno e.g. discusses the workings of the urban space in Djakarta as absolutely crucial for the construction of a national Indonesian subject as well as for forms of resistance that work against dominant political forces.xvi Jyoti Hosagrahar discerns ‘indigenous modernities’ in Delhi, arguing that the confrontation between imported modernism and local realities created urban and dwelling spaces where colonialism was negotiated rather than imposed – acknowledging the two way logic of spaces that are on the one hand imposing a certain order while on the other hand opening up cracks and gaps that allow for inventive reinterpretations and uses that exceed what was intended by those who planned them.xvii 5. New conceptual tools? Given all this, we should question whether we can get along in architectural history and theory with the categories we have used thus far. Is ‘modernism’ still a term that might be vital as an adequate response to modernity (or modernities)? Or terms such as ‘avant-garde’? Is there still an ‘avant-garde’ out there or is the term only useful to describe a historical phenomenon? What about ‘utopia’? Are postmodernism, poststructuralism and postcolonialism adequate terms to describe our current condition and the responses to it? Is critical regionalism still something we want to advocate? And what about categories such as postcriticality, posthumanism or non-representational theory? One can discuss all these different concepts, and they all might be useful to some extent. For me the most pressing issues however have to deal with two questions: 1) How to frame the ‘epistemology of architectural discourse’? 2) How to engage with issues of sustainability? With respect to the first question, I would like to refer to Duanfang Lu. In her chapter for ‘The Sage Handbook of Architectural Theory’, called ‘Entangled Modernities’, she claims that “the recognition of other modernities has to be posited at the level of epistemology in order to imagine an open globality based not on asymmetry and dominance but on connectivity and dialogue on equal basis. It is important (…) to recognize the legitimacies of different knowledges.”xviii This is an interesting position to take, although I must admit that I don’t find it easy to implement in practice. Duanfang Lu herself refers to the Chinese architectural discourse of the 1960s, which linked up discussions of sobriety with references to vernacular architecture elsewhere in the world – bypassing as it were the First and Second World in a conversation that only concerned ‘peripheral’ countries. I can see that she understands this type of discourse as one that doesn’t give in to hegemonic assumptions about the role of center and periphery. I am not so sure, however, whether it is really different epistemologies that are at stake here. In a way Gülsüm Baydar hints upon a similar attitude, when she insists on the incommensurability of different kinds of knowledge: “Writing postcoloniality in architecture questions architecture’s intolerance to difference, to the unthought, to its outside. For it embraces the premise that ‘when the other speaks, it is in other terms’.”xix This position, which might be inspired by Jean-François Lyotard’s idea about ‘Le Differend’, however threatens to make exchange very, very difficult. If we cannot translate other types of knowledge into terms that are understandable to us (and by ‘us’ I refer in this case to the international community of scholars in architectural history and theory), I fail to see how we would be able to respect them. In that sense I find Esra Akcan’s position more promising. Akcan wonders whether current trends of postcolonial criticism have not been too much about exposing how ‘Architecture’ is exclusive rather than inclusive, while they fail to offer any directions for a critical practice.xx For her it makes sense to rather explore a ‘humanist’ trajectory of postcolonial theory, a trajectory that would emphasize (commensurable) diversity instead of (incommensurable) difference. The second question I raise – about sustainability – is also very pertinent and topical. The current insights into the anthropogenic phenomena of climate change, decreasing bio-diversity and overconsumption of resources necessitate us to re-think our relation to the planet. The built environment is one of the major factors contributing to all that, so we have to be aware in architecture about these issues. For me they necessitate a re-engagement with the legacy of modernism, because, as I wrote recently in an article with my colleague Han Vandevyvere: “Rather than seeing modernism as purely technocratic, and hence as the culprit responsible for the depletion of natural resources, we claim that these social and emancipatory aspects of modernism should be taken as the starting point to reframe, renegotiate and reinvent the ‘project of modernity’ advocated by Jürgen Habermas. Modernism, we claim, was indeed about negotiating the constraints of nature, about using science and technology to arrive at a more just society. Translated into the terminology of sustainability, we could state that it was about ‘people’ taking into account ‘planet’ and accepting ‘profit’ as a driving force. Hence, rather than discrediting modernism, we should build upon its legacy of negotiating natural, technological, social, political and cultural conditions in order to further the emancipation of individuals and collectivities.”xxi These considerations can be related to what Greig Crysler, Stephen Cairns and I stated in our joint introduction to ‘The Sage Handbook of Architectural Theory’, where we invoked three different, though related, concepts as a means of fleshing out the idea of an architectural theory in an expanded field: provincializing (Chakrabarty), worlding (Spivak) and gathering (Latour). Provincializing refers to the need to simultaneously decenter and activate principles such as rationality, secularism, or social justice – which are not only central ideas in modernism, but at the same time inspirational concepts that drive progressive forces in many different situations and practices. By recognizing the situated character and differences in many different parts of the world, we should not, on the other hand, agree that these differences necessarily discredit these ideals as ideals. Worlding, a term used by Spivak (1990), draws attention to the epistemic violence implicated in imperialism, in particular ‘the assumption that when the colonizers come to a world, they encounter it as uninscribed earth upon which they write their inscriptions’ (1990, 129). The idea of the ‘Third World’ is, for Spivak, a striking instance of this homogenizing process. Yet, this process also contains within it possibilities for a ‘counter-worlding’ or a new ‘worlding of the world’ in which alternate, situated possibilities for being in the world are articulated. As in Chakrabarty’s logic of provincialization, this is a self-contradictory process that involves ‘un-learning’ the privileges of speaking from the centre as much as it does learning and propagating new forms of knowledge. Latour’s (2004) reappropriation of Heidegger’s conception of ‘gathering’, brings us to the most architectural framing of these three related themes. Latour’s consideration of contemporary technology, leads him to consider the way certain things have gathering or relational effects. The work of theory, for Latour, is not merely a matter of ‘debunking’, but one of assembly. The theorist ‘is one who offers the participants arenas in which to gather’. The critic is ‘the one for whom, if something is constructed, then it means it is fragile and thus in great need of care and caution’. Hence we can see that we as theorists and historians have to pay attention to these ‘matters of concern’ – which is why I didn’t want to conclude this lecture without at least mentioning the issue of sustainability, a major ‘matter of concern’ which should be at the forefront of our thinking.xxii i . Marshall Berman, All that is Solid melts into Air. The Experience of Modernity (1982), Verso, London, 1985, p. 16 ii . Jürgen Habermas, "Modernity - an Incomplete Project", in Hal Foster (ed.), The Anti-Aesthetic. Essays on Postmodern Culture, Bay Press, Seattle (Wash.), 1991 (1983), pp. 3-15, p. 9. iii . Jean Baudrillard, "Modernité", in La modernité ou l'esprit du temps, (Biennale de Paris, Section Architecture, 1982), L'Equerre, Paris, 1982, pp. 28-31, p. 29 (translation into English hh) iv . Marshall Berman, All that is Solid melts into Air. The Experience of Modernity (1982), Verso, London, 1985, p. 15 v Duangfang Lu, “Entangled Modernities in Architecture”, in Greig C. Crysler, Stephen Cairns, Hilde Heynen (eds.), The Sage Handbook of Architectural Theory, Sage, London, 2012, pp. 231-246, p. 231-232. S. N. Eisenstadt, “Multiple Modernities”, in Daedalus, Vol. 129, No. 1, Winter, 2000), pp. 1-29, p. 1 vi vii Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: postcolonial thought and historical difference, Princeton: Princeton university press, 2000 viii Jyoti Hosagrahar, “Interrogating Difference: Postcolonial Perspectives in Architecture”, in Greig C. Crysler, Stephen Cairns, Hilde Heynen (eds.), The Sage Handbook of Architectural Theory, Sage, London, 2012, pp. 70-84, p. ix Hilde Heynen (2002). Coda: Engaging Modernism. In: Henket H., Heynen H. (Eds.), Back from Utopia. The Challenge of the Modern Movement. Rotterdam: 010, pp. 378-399, p. p. 388. x xi Edward Said, Orientalism, New York: Pantheon, 1978, p. 5 Gülsüm Baydar Nalbantoglu, “Toward Postcolonial Openings: Rereading Sir Banister Fletcher's 'History of Architecture.'” Assemblage, no. 35 (April 1998): 6–17. Mrinanlini Rajagopalan, “Preservation and Modernity: Competing Perspectives, Contested Histories and the xii Question of Authenticity”, in Greig C. Crysler, Stephen Cairns, Hilde Heynen (eds.), The Sage Handbook of Architectural Theory, Sage, London, 2012, pp. 308-324 Wilma Fairbank, Liang and Lin. Partners in Exploring China’s Architectural Past, Philadelphia: Univrsity of xiii Pennsylvania Press, 2008 Abidin Kusno, “Rethinking the Nation”, in Greig C. Crysler, Stephen Cairns, Hilde Heynen (eds.), The Sage xiv Handbook of Architectural Theory, Sage, London, 2012, pp. 213-230, p. 213. xv Hilde Heynen (2013). Space as receptor, instrument or stage. Notes on the interaction between spatial and social constellations. International Planning Studies, 18 (3-4), 342-357. xvi Abidin Kusno, Behind the Postcolonial: Architecture, Urban Space and Political Cultures in Indonesia, London: Routledge, 2000. xvii Jyoti Hosagrahar, Indigenous Modernities: Negotiating Architecture and Urbanism, London: Routledge, 2004. xviii Duangfang Lu, “Entangled Modernities in Architecture”, in Greig C. Crysler, Stephen Cairns, Hilde Heynen (eds.), The Sage Handbook of Architectural Theory, Sage, London, 2012, pp. 231-246, p. 241. Gülsüm Baydar Nalbantoglu, “Toward Postcolonial Openings: Rereading Sir Banister Fletcher's 'History of xix Architecture.'” Assemblage, no. 35 (April 1998): 6–17. xx Esra Akcan, “Postcolonial Theories”, in Elie G. Haddad and David Rifkind, A Critical History of Contemporary Architecture 1960-2010, Farnham: Ashgate, 2014, pp. 115-136. xxi Han Vandevyvere, Hilde Heynen (2014). Sustainable Development, Architecture and Modernism: Aspects of an Ongoing Controversy. Arts (3), 350-366 xxii Greig S. Crysler, Stephen Cairns, Hilde Heynen (2012). Introduction 1. Architectural Theory in an Expanded Field. In: Crysler C., Cairns S., Heynen H. (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Architecture Theory. London: Sage, 1-21