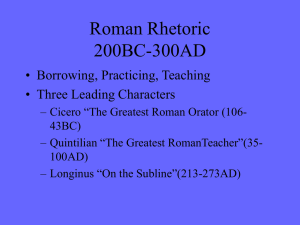

MARCUS TULLIUS CICERO – BIOGRAPHY

advertisement

MARCUS TULLIUS CICERO – BIOGRAPHY (http://www.egs.edu/library/cicero/biography/) Marcus Tullius Cicero, sometimes referred to as “Tully” was born on the 3rd of January in 106 BCE into a lower aristocratic family of the equestrian order in Arpinum just south of Rome. He lived during the tumultuous times of the civil war outbreaks of the Roman republic and its impending decline, eventually becoming an enemy of the state. Marcus Tullius Cicero was murdered by decree on December 7th in the year 43 BCE. He was a lawyer, statesman, politician and philosopher and came to be known as one of Rome’s greatest orators. Marcus Tullius Cicero was an avid thinker and writer and his texts include political and philosophical treatises, orations and rhetoric, the latter of which has come to be known as “Ciceronian rhetoric,” and an amass of letters. Above all, he considered politics of utmost importance, which should be effectively influenced by philosophy, and politics his greatest achievement. Born into a land-owning and respected family of the provincial gentry, Marcus Tullius Cicero was well cared for and well educated in his childhood. He was the eldest of two sons. His father, whom he was named after, did not have much of a public life due to his physical disabilities yet was extremely learned and intellectual. His son became a renowned student, developing a love and penchant for philosophy, taking up poetry and successfully translating Homer. According to Plutarch’s biography, he was so auspiciously talented as a young student it soon afforded him the attention and opportunity to study in Rome. While his intellectual prowess would soon gain him recognition and entry into the Roman elite, coming from second tier aristocracy inhibited him from entering into politics directly. Therefore, Marcus Tullius Cicero had to either enter via military service or through the practice of law. Prior to his commitment to the field of law, he did serve in the military, albeit briefly, under Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo and Lucius Cornelius Sulla, between the years 90-88 BCE. This was not the path for the young intellectual and he followed the opportunity in Rome to study under the renowned stoic and Roman politician, Quintus Mucius Scaevola. He studied alongside Servius Sulpicius Rufus and Titus Pomponius, later known as Atticus. The former Cicero would come to regard as a far better lawyer then he, the latter became Cicero’s closest confidant and consult, like a “second brother”. Due in part to his family and in part to his intellectual prowess, Marcus Tullius Cicero received patronage from the wellregarded Roman consuls, Marcus Aemilius Scaurus and Lucius Licinius Crassus, the latter of whom Cicero regarded most and who became a significant mentor. His love of philosophy also flourished during this time of study in Rome (and subsequently over the rest of his life) in which he gained a broad range of philosophical scholarship from the Epicurean school to that of the Stoics. He and Atticus met with Phaedrus when he came to Rome and exposed them to Epicurean philosophy. Atticus would become an Epicurean, while Cicero mostly rejected it. Years later Philo of Larissa, then head of Plato’s Academy in Athens, came to Rome and Marcus Tullius Cicero apparently devoured the teachings from the Academy and particularly of course, Plato’s philosophy. While it is said that he disregarded Plato’s theory of Ideas, he came to admire his discussions on morality. He also soon met Diodotus, a Stoic, who expanded Cicero’s understanding of Stoicism, even though Cicero was not entirely convinced of it, and Logic. Cicero highly regarded the philosopher and the two became close friends; Diodotus would come to live with Cicero until his death. While he studied philosophy, and rhetoric, his dedication to jurisprudence he favored and it soon led to his obtaining his first major case by 80 BCE in which he defended Sextus Roscius on the charge of patricide (killing one’s father). It was a very big case and put Marcus Tullius Cicero in a challenging position as he accused friends of the general Sulla (whom he had served under) with the actual charge of murder. He was triumphant and Roscius was acquitted. Soon thereafter, Marcus Tullius Cicero left Rome for Greece, Rhodes and Asia Minor. He met with Atticus, the now ‘full-fledged’ Epicurean who became an honorary citizen of Athens, and was introduced to Athenian society. In addition to further philosophical study he expanded his knowledge and style of rhetoric with Apollonius Molon of Rhodes, which would have a lasting impact on his oratory. During this year, presumably 79 BCE, Marcus Tullius Cicero was married to Terentia. Most likely a marriage of convenience, Terentia came from the socially and economically noble family, Terenti Varrones, and was purportedly more interested in Cicero’s career than in their household management. The couple produced two children, a daughter, Tullia, and a son, Marcus, whom Cicero hoped would become a philosopher. (His son did not, but eventually became involved in politics after his father’s murder, and under Augustus took action against Mark Antony in honor of his father). Not only did Marcus Tullius Cicero prove himself as a lawyer, his improved skills at oration began to make an impact and his career in politics started to flourish. He was successfully elected to each main Roman government office—quaestor, aedile, praetor and consul—all at a considerably young age. Another challenging move by the incredulous philosophical politician was his exposing the Catiline conspiracy in 63 BCE while he was serving his term as consul. The conspiracy was attempting to forcefully take over the Roman state. Marcus Tullius Cicero ordered the executions of five of the conspirators without a trial. Execution without trial was a risky action to take by the statesman, and earned him both praise and criticism. Nonetheless, Marcus Tullius Cicero was much loved and admired. He also became a member of the Roman Senate, which while not wielding any direct authority, was a very influential body in Roman political life and was depended upon for advice and counsel. The Roman republic was heading towards instability and it proved to be a difficult and trying time for the statesman. Power struggles would leave him in precarious positions, not just politically. During what is considered the First Triumvirate, Marcus Tullius Cicero chose to remain loyal to the Senate and the idea of the Republic, however mythical the idea was in practice, rather than join Julius Caesar, Pompey and Crassus in taking control of the Roman state. In retribution, a law was passed in the tribune Clodius, 58 BCE, to retroactively punish any order of execution without trial. This led to Marcus Tullius Cicero’s exile, as his punishment was a dismissal of Roman citizenship, which included property. After approximately a year and a half of exile, Marcus Tullius Cicero was restored to Rome due to another shift in the political landscape. He was allowed to practice law, and had to, as he now owed a debt to the Triumvirate for terminating his exile, yet he was not allowed to practice politics. Between his exile and the subsequent years in which he could not be a statesman, Marcus Tullius Cicero enriched his studies in philosophy and began to write as well. Roughly between the years 55 and 51 BCE, he wrote his infamous texts: De republica (On the Republic) De legibus (On Laws), De officiis (On Duties). On the Republic, except for Book VI containing the Dream of Scipio, was lost since the middle ages, but reconstructed from fragments, quotes and a palimpsest found in the 19th century. The books collectively focus on the conditions for republic, justice, human nature and citizenry. Marcus Tullius Cicero very much identifies with the Greek ideals of justice and a commonwealth following the Aristotelian view of “giving each their due,” and the Platonic paternal notion of a ruling justice. He contrasts with a Roman individuating sense of glory and honor in favor of a virtuous commitment to justice. While the dialogue in On the Republic was set in the past, the dialogue for On Laws was set in Cicero’s day in which he, his brother and his friend are the main figure of the dialogue. Once again, only fragments remain, but the premise is that of law and justice being of the highest reason and while it can be corrupted, and must be exposed and discarded, it is in fact man’s natural inclination as reason comes from nature. The participants go on to discuss an ideal code of law that is essentially a modified representation of the then contemporary Roman law code. His final writing of this period, On Duties, is often considered Cicero’s “republic.” It in fact very much parallels Plato’s Republic positing a conflict between justice and individual advantage that is in essence illusory as ethics, being true to the ethical, would disavow such apparent conflict. Maintaining the inseparability between ethics and politics, Marcus Tullius Cicero puts forth an exemplifying case that acknowledges the too oft corruption of political power and self advantage as that being a misunderstood relationship and confidence of ethical duty as self advantageous. The latter is in effect the “moral” of the story, such that conflict and tension between the two exists, naturally, yet justice, and ethical duty, properly understood, is in fact always advantageous for the one, and the many. Marcus Tullius Cicero’s philosophy was primarily in service of his role as a politician and to his commitment to the ideal of a/the republic. And, in particular, to the Roman republic in which, or for which, he translated much Greek philosophy and developed new vocabularies in Latin to aid in translation and understanding for this particular audience—many of our words used today come from this development such as: morals, image, individual, property. The main schools of thought that Marcus Tullius Cicero engaged with, whether in disagreement or in affinity, were the Academy Skeptics, the Epicureans, the Stoics and the Peripatetics. He was most aligned with the Academy Skeptics and the general view that nothing can be known with certainty and that ‘truth’ is essentially relative probability. The skeptic approach appealed to him especially as an effective strategy in law and politics. The skeptic must seek as many perspectives as possible and tease out as many probabilities in order to present a valid argument. As well, it also accepts and advocates malleability as probabilities and perspectives fluctuate over time, and ‘evidence’ proves otherwise. While he was most aligned with the Academy he also incorporated aspects of the other Hellenistic philosophies, as Skepticism could not attend as well to the practice of jurisprudence in the everyday with the everyday man. Thus, through a skeptical approach, he looked to the Stoics for a philosophy as the best probable form to attend to the significance and sanctity of law and justice in society. His Stoic ideas are very much present in his writings on law and duties in which natural law, a product of reason, is man’s guiding principle. When employed ‘properly’ this creates a set of laws and a community of men that share in their duty to their just collectivity and thus to themselves. As such, political participation is then an expected virtue. Perhaps one could say that his overarching philosophy essentially revolved around justice and its possibility. Marcus Tullius Cicero would continue his engagement with philosophy and writing as the Triumvirate eventually collapsed and he was again exiled from Rome for (barely) siding with Pompey over Caesar, who became first Roman emperor in 48 BCE. Caesar soon pardoned Marcus Tullius Cicero a year later, but he was forced to abstain from active political life. Following the political upheavals that were ensconcing Rome, he and his wife divorced. It is said that he believed his wife to have betrayed him, yet it wasn’t clear how specifically he meant as such. It seems the official divorce occurred in 51 BCE and a few years later, either in 46 or 45 BCE, he married a young women. It is presumed it was out of a need for financial gain, as he owed the debt of his x-wife’s dowry. His second marriage was short lived and Marcus Tullius Cicero was soon thereafter ensconced with bereavement over the loss of his daughter whom he was enamored with and in which his text on death and consolation derived from: The whole life of the philosopher is a preparation for death. Marcus Tullius Cicero would have a final role in Roman politics before his death in the period immediately following the murder of Caesar; members of the Senate executed the latter in 44 BCE. Marcus Tullius Cicero was witness to the murder but was presumably not a part of the conspiracy. While another power struggle ensued, among Mark Antony, Marcus Lepidus, and Octavian (who would come to be called Augustus), Marcus Tullius Cicero hoped that he could assure the possibility for the continuance of the Roman republic. Addressing the Senate once again, Marcus Tullius Cicero made a series of orations that are known as the Philippics. The name comes from an infamous moment in Greek history when Demosthenes orated the rise of the Athenians against Philip of Macedon. In Cicero’s case, it was a call to rise against Mark Antony in support of Octavian and the survival of the Roman republic. Although this moment of voice has become infamous, it failed, one could say, by subversive power as opposed to justice. Mark Antony and Octavian partnered together in taking over Roman power and Marcus Tullius Cicero was to become an enemy of the state since Octavian chose not to protect him. On the orders of Mark Antony, the man of justice was murdered—slit in the throat with his head and hands decapitated, which were then hung on the podium in the Senate as a warning. It has been noted that Marcus Tullius Cicero, upon capture, told his would be murderers, “there is nothing proper about what you are doing, soldier, but do try to kill me properly.” Marcus Tullius Cicero was a dedicated and committed man of justice, of justice as probability. He was extremely prolific, and while, and only because he was detained from political practice, wrote extensively on philosophy through dialogic writing. He wrote as well his numerous orations that reveal both his political philosophy as well as his political prowess in their provocative challenging rhetoric. Finally, he was an ardent and prolific letter writer having exchanged countless letters, most often with Atticus and his brother, in which hundreds remain in archive. His legacy is long lasting and had its greatest effect in the Roman era and later during the Renaissance. St. Augustine credits Marcus Tullius Cicero’s thought and writing with his pursuit of a greater purpose in life. His political thought and activism is said to have inspired the figures of both the American Revolution and the French revolution. The translations and writings of Marcus Tullius Cicero are often considered to be the bedrock of much European philosophical training and understanding and thus long-lasting effect. Yet in the more modern era, discrepancies in his thought and character, revealed through revisionist insight and the distribution of his private letters, have very much tainted and caused great criticism of his ideal yet subsequently contradictory practice.