Submission to the Family Law Council - Attorney

advertisement

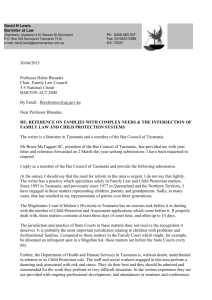

Friday, 8 May 2015 To: Professor Helen Rhoades Chair, Family Law Council c/- Family Law Council Secretariat Attorney-General’s Department 3-5 National Circuit BARTON ACT 2600 SUBMISSION TO FAMILY LAW COUNCIL ATTORNEY-GENERAL’S REFERENCE REGARDING CHILD PROTECTION On behalf of the Family Law Practitioners Association of Tasmania, 1 we thank the Family Law Council for the invitation to comment in regards to the Attorney-General’s Terms of Reference regarding the relationship between child protection and the family law system. We also thank your secretariat for the extension of time in which to provide this submission. We will refer to the questions raised in your letter of March 2015 in the order provided: 1. Question 1, Part I: Two Places, Two Mindsets 1.1 In Tasmania, child protection proceedings are not dealt with by specialist judiciary, but instead by magistrates sitting in a different division of the Magistrates Court of Tasmania. Legal services for child protection have now been assigned to the state Director of Public Prosecutions. 1.2 FLPAT notes that litigants who come to the attention of both the child protection and family law systems tend to be: Reliant on government benefits and/or of modest means; Have multiple risk factors facing the family such as mental health issues, homelessness, offending, drug use, family violence, low IQ, sexual abuse allegations or alcohol abuse. 1 The Family Law Practitioners Association of Tasmania Inc. (FLPAT) is the professional association for family lawyers in Tasmania. With the majority of the state’s family and child protection lawyers as members, we provide advocacy, continuing legal education and networking opportunities and meet regularly with state and federal judiciary and affiliated stakeholders regarding the family law and child protection spheres. 1.3 Given the parlous state of Legal Aid in Tasmania at present, most of them are self-represented litigants in each jurisdiction. 1.4 FLPAT agrees with the view that the same issues are being ventilated in both courts; however, in the Federal Courts the process tends to be Court-managed and driven2 whilst in the State Court the process is still managed and driven mainly by the prosecuting authority (the DPP). 1.5 There are provisions for Magistrates to conduct what are known as “section 52 conferences” in State-based proceedings, but in practice these are run by a mediator employed by the Court. Anecdotal experience is that they are far more effective in driving and case-managing the proceedings and giving an early indication of outcome if state Magistrates were to run them more often. 1.6 We address some of the practical matters in this regard below in addressing some of the other questions posed in the Request for Comment. However, proceedings in state courts are affected by: 1.6.1 State judiciary who are not specialised in this area, operating in facilities and systems designed primarily for criminal law jurisdiction. In this regard, Families involved in Child Protection proceedings mix in the same buildings with those involved in criminal law matters. Children attending Court are exposed to what can be a confronting cohort of litigants. It is entirely inappropriate for families and young children to be physically lumped together with those accused of offences and crimes. The Magistrates Court does try to mitigate this by listing matters at different times but the problem persists. There is no separate Court building or entry to the Court precincts. Criminal matters are heard either side of child protection matters. 1.6.2 Child protection being represented in court by the Director for Public Prosecutions and failing to comply with court directions designed to ensure procedural fairness. 1.6.3 State Magistrates routinely interview children directly. Given the physical precincts of the court, to say this is not occurring in a child-friendly environment is an understatement. It is a vastly different experience to proceedings in the Federal Courts, where children do not meet the judicial officer as a general rule. 1.6.4 Tasmania does not have specialist child protection Magistrates. Magistrates are part of the general list and decide a wide range of matters - civil, criminal and coronial. Federal Court judicial officers in Tasmania determine exclusively matters brought pursuant to the Family Law Act. FLPAT is concerned, that in some instances, the Magistrate may not have the same degree of expertise in dealing with children and dealing with child-related matters as do their Federal counterparts, simply by virtue of the wide range of matters which they must deal with on a daily basis. 2 Particularly noting the case management and process in the Magellan program 1.6.5 The examination of whether a child is "at risk" in a parent's care rarely involves an examination of the positive steps that parents have taken. Given the focus on risk and whether negative conduct has occurred, parental reactions to proceedings view them as highly prosecutorial, and view a state agency as trying to remove their child from their care rather than acting in concert with the family. This litigant view of "the state vs the individual" is more reminiscent of criminal proceedings. 1.7 Equally, FLPAT notes two common sets of events which indicate cultural problems within child protection and their attitude to the family law sphere: 1.7.1 Child protection is often consulted immediately before the commencement of proceedings – either by practitioners, or litigants directly - about whether they intend to intervene or take action. This is often in the context of a party making an application that a child spend time with them (or be recovered to them under a Recovery Order) but allegations have previously been raised against that parent. The child protection response is unfailingly along the lines of "we do not seek to act at this time as the child is appropriately protected. We will review our position if this circumstance changes." This is not illuminating as to any future child protection action, nor gives any indication of whether they will treat the matter with seriousness. 1.7.2 No member can recall child protection acceding to a section 91B request to intervene. Indeed, Tasmanian child protection has gone to great lengths to not intervene in a case, including to the extent of a Family Court Full Court appeal. However, there are many anecdotal accounts of Child Protection either simultaneously issuing proceedings in the State Court or issuing proceedings shortly after. 1.8 FLPAT takes the view that a greater willingness to intervene may be a more proactive and streamlined approach. There is, however, a cultural unwillingness for Child Protection to be involved outside its comfort zone of the State jurisdiction. 2. Question 1, Part II and Questions 5 and 6: Early Information Sharing and solutions 2.1 FLPAT submits that information sharing at an early stage in proceedings in critical. 2.2 The present default position is that, in Commonwealth proceedings, subpoenas issue for any child protection file – voluminous, repetitive, heavily redacted, a heavy administrative burden to supply and store, and difficult for litigants (especially self represented litigants, or for those paying the costs of a practitioner to deal with and inspect.) The subpoenas often disclose some thousands of pages. 2.3 Equally, FLPAT is not aware of any situation where state courts have subpoenaed a federal court file. They only have information generated from Family Law proceedings if there has been an order that a Family Report, Final orders or similar are to be sent to Child Protection – though again, anecdotally, we are unaware of this having occurred. It needs to be recalled that the majority of private civil litigants are not likely to require intervention by child protection. When child protection receives a notification, it ought request any formation from the Family Law Courts and have basic information supplied in electronic form. 2.4 Notification Summary: FLPAT submits that there be more streamlined, automatic sharing of information. Having received the Notice of Risk filed in each case, Child Protection ought to provide a summary of any notifications received. This may not take any more time than the current time-consuming task of responding to subpoenas and should replace subpoenas filed. It would also ensure information is before the Family Law Court when both parties are unrepresented. 2.5 Early Reporting: One option which has been presented would be the introduction of, for lack of a better phrase, "Initial Magellan" reports from Child Protection in cases where the Notice of Risk presents issues of concern to the judicial officer or Independent Children's Lawyer. The benefits of such a process involving streamlining of the disclosure process, and assisting all involved to concentrate on those issues of greatest relevance. 2.6 The request for such a report would be anticipated as originating from a judicial officer or registrar in chambers, or upon written request of an ICL. Such reports would take the form of a one-page pro forma document, outlining: 2.6.1 The names of the children and parties involved; 2.6.2 Whether there has been any past or current proceeding under state child protection legislation, and if so, the date and nature of any Order made; 2.6.3 Basic details as to any substantiated or unresolved allegation brought to the attention of child protection - as a starting point, the year and nature of the allegation raised; 2.6.4 Any intended action to be taken by child protection, having received the Notice of Risk. 2.7 Report Disclosure: FLPAT notes that the Family Courts already routinely make orders providing child protection with Expert and Family Reports. The opposite does not occur. It would be helpful if, when a Form 4 is received, any such reports are provided to the Family Court. This may require a change to section 103 of the Children’s Young Persons and their Families Act 1997 but more likely can be effected by a memorandum of understanding between the entities (as currently exists in any event with respect to subpoenaed information). 2.8 Technology Access: The advance of technology (for example, subpoenaed documents are now all provided in disc form) allows easier information flow. There would be practical and administrative benefits if child protection could be added to the Portal (both as a party, and in regards to any documents released.) 2.9 Expert Collaboration: FLPAT also considers there would be benefit from professional collaboration between Child Protection Professional practice advisors (i.e. psychologists) and the Family Consultants to ensure a common view point in looking at issues of risk, family attachment, assessment of family violence and parental capacity, and reporting to courts around these issues. 2.10 Access to Community Services: Finally, FLPAT notes that families involved in child protection litigation are routinely linked in to a service such as Baptcare, the Salvation Army and the like who offer intensive Family support and who report to Child Protection. The experience is that this does not occur by way of referrals by the Federal Courts, presumably because the same funding arrangements do not exist. 3. Question 2: Problems for All 3.1 Given all the issues raised above, practitioners find it difficult to adequately explain to clients (who are usually at crisis point anyway) the legal complexities of the difference in approach between the Courts. 3.2 The reality is that in the current funding climate, these most vulnerable of clients are regularly refused Legal Aid for either lack of merit or a lack of available funds. As a result the ICL (or Separate Representative) and the Courts are dealing with self-represented litigants. This usually means matters take longer to resolve in an emotionally charged environment. 3.3 The capacity for some families to enter into Family Court consent orders (with the Secretary either as a party or consenting to the order and often with extended family members involved) is likely to remove more matters from the Child protection jurisdiction and allow extended family the autonomy to parent children in the absence of the Secretary being the legal guardian. 3.4 In the past, the Legal Aid Commission prioritised funding such clients. This is no longer possible unless Legal Aid funding is increased. It may be more cost-effective in the long term as it causes less matters to proceed to hearing, and a smoother transition between a child protection order and (as the family becomes better functioning) a Family Law Act order. 3.5 Practitioners also report continuing confusion between parents and child protection staff as to the concepts of "guardianship" and "custody" under the state child protection legislation, and "parental responsibility" under the Family Law Act, and who should hold responsibility, decision making power, and be able to access information regarding major long-term issues regarding children subject to state Orders. 3.6 Other options which may assist are: 3.6.1 For the Federal Courts to have the power to compel the Secretary to intervene; or 3.6.2 For a change in culture which would see the Secretary intervening more often, if only for a limited period; or 3.6.3 State Magistrates being able to make consent orders pursuant to the Family Law Act; or 3.6.4 Reform by the state system to introduce specialist Child Protection Magistrates. 4. Question 3: The Family Law Act in state courts 4.1 FLPAT is of the view that, theoretically, there would be benefits in state courts having greater ability to exercise power under the Family Law Act. However, in practice, this would be unworkable. 4.2 State courts have limited existing power under section 68R to vary parenting orders when making or varying Family Violence Orders. We are unaware of any report of this power having been used by a State Magistrate. 4.3 There is a clear benefit in enabling Children’s’ Courts to make parenting orders. Often there are family members who may more properly be given parental responsibility rather than the Secretary. Whilst this can be done in the context of a care and protection order, Family Law Act orders last until they are changed rather than being finite. Also, towards the end of a care and protection order, for the family to be able to move seamlessly into a Family Law Act order would ensure stability for children. At the moment they need to access another jurisdiction, and these families are often not equipped to navigate the Federal Courts by themselves. 4.4 However, for the reasons stated under Question 1, Part I above, State Magistrates have very different training and experience from federal judiciary and a divide in practice and understanding may become apparent. There is also the issue of where appeals may lie. 4.5 There is also the administrative issue of Legal Aid funding – at present federal matters and statebased matters are funded by the Commonwealth and the State, respectively. 4.6 Given the current logistical, training and interface issues with state courts, FLPAT would not support further powers under the Family Law Act being transferred to state courts. 5. Question 4: Child protection powers in the Family Court / Federal Circuit Court 5.1 FLPAT is strongly supportive of the Federal Courts being able to exercise power under state child protection legislation. 5.2 FLPAT recognises the nature of the constitutional and practical considerations in transferring state child protection powers to the Commonwealth judiciary, particularly given the political considerations around responsibility and referral of powers, and the limitations of Re Wakim; Ex parte McNally. 5.3 However, we note the experience of Ray and Anor & Males and Ors.3 In that case, child protection was requested to intervene, and refused. The judicial officer required their joinder to the case, which was overturned on appeal to the Full Court. The greatest irony of the case is that child protection did, after this appeal, intervene in the case – at great legal cost to the taxpayer, and not delaying their participation in a case where two children were at real risk. 5.4 Equally, however, it would not be practical for Federal Courts to take on the primary workload of child protection in the current resource-poor environment. For instance, an Assessment Order under the CYPFA only lasts for 28 days, and is capable of extension only for a further 28 or 56 days. The hearing of the Application may be adjourned only once, and for no more than 14 days, except in special circumstances.4 Equally, proceedings for a Care and Protection Order must proceed from Application to Hearing within 10 weeks, except in exceptional circumstances.5 State judiciary, to their credit, are often able to comply with some margin of error and the legislative intention of prompt investigation and resolution of abuse allegations is appropriate to the nature of the cases involved. 5.5 Given that the duration of a Care & Protection Order hearing often exceeds one day (and in the experience of practitioners, can run to 5 or 6 days) it is FLPAT's view that it is beyond the current capacity of the Commonwealth courts to provide these services, or the additional 2 to 3 judicial officers to meet the workload around the state, particularly where warrants or urgent orders are sought. 5.6 FLPAT considers that the duplication of assessments, interviews, conferences, negotiations and litigation between the two systems is a gross abuse. Leaving aside the cost to the public purse, the 3 [2009] FamCA 219 per Benjamin J Children Young Persons and their Families Act 1997 (Tas.) s. 25 5 Children Young Persons and their Families Act 1997 (Tas.) s. 45 4 effect on the mental health of parties and the greatly increased risk of systems abuse on children cannot be justified. We are aware of, and commend, the views of Julie Jackson in her paper Bridging the Gaps between Family Law and Child Protection in regards to the necessity of having a single court determining cases where there are both child protection and parenting order concerns. 5.7 A practical measure to ensure that this does not occur would be to enable family law judicial officers to also hold simultaneous state commissions in the relevant Supreme or Magistrates Court. Whilst the technical and constitutional issues would be significant, the training and expertise that these judicial officers could bring to family law matters involving abuse allegations, and the reduction in the risk of systems abuse and expenditure, would have great advantages. 5.8 The unanimous view of those practitioners who have provided their feedback to FLPAT is that there is merit in federal courts being able to take on board limited jurisdiction to deal with child protection matters, given their expertise in dealing with children and knowledge of relevant social science. FLPAT presents the Dual Commission model as one possible way of helping this to occur. 5.9 A secondary way of trying to prevent conflict between courts would be the mandatory introduction of pre-proceeding Signs of Safety Conferences (noting the Western Australian practice in this regard.) This would allow all involved to know the parties' views, expectations and the most appropriate way to deal with matters. 5.10 In this regard, again, we commend the views of Julie Jackson in her report regarding the benefit and process that such a Conference could take. If such a Conference was unsuccessful in preventing simultaneous federal and state proceedings, it would be appropriate that the child protection application be removed to the federal court, and heard together. 6. Finally, we have to hand the submissions of Mr David Lewis, Barrister, as a member of the Bar Association of Tasmania. We concur that Mr Lewis is a senior and experienced practitioner in this area and that his experiences and views of the current system are reinforced by the representations of our own members. We commend his views to the Council. Yours faithfully, Joseph Petersen (Chair), on behalf of Family Law Practitioners Association of Tasmania Inc.