*Fashion* by James Madison, National Gazette, March 22, 1792

advertisement

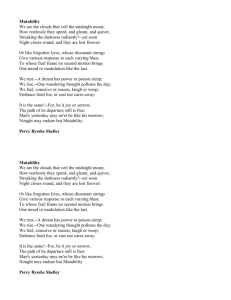

“Fashion” by James Madison, National Gazette, March 22, 1792 An humble address has been lately presented to the Prince of Wales by the buckle manufacturers of Birmingham, Wassal, Wolverhampton, and their environs, stating that the buckle trade gives employment to more than twenty thousand persons, numbers of whom, in consequence of the prevailing fashion of shoestrings & slippers, are at present without employ, almost destitute of bread, and exposed to the horrors of want at the most inclement season; that to the manufactures of buckles and buttons, Birmingham owes its important figure on the map of England; that it is to no purpose to address fashion herself, she being void of feeling and deaf to argument, but fortunately accustomed to listen to his voice, and to obey his commands: and finally, imploring his Royal Highness to consider the deplorable condition of their trade, which is in danger of being ruined by the mutability of fashion, and to give that direction to the public taste, which will insure the lasting gratitude of the petitioners. Several important reflections are suggested by this address. I. The most precarious of all occupations which give bread to the industrious, are those depending on mere fashion, which generally changes so suddenly, and often so considerably, as to throw whole bodies of people out of employment. II. Of all occupations those are the least desirable in a free state, which produce the most servile dependence of one class of citizens on another class. This dependence must increase as the mutuality of wants is diminished. Where the wants on one side are the absolute necessaries; and on the other are neither absolute necessaries, nor result from the habitual œconomy of life, but are the mere caprices of fancy, the evil is in its extreme; or if not, III. The extremity of the evil must be in the case before us, where the absolute necessaries depend on the caprices of fancy, and the caprice of a single fancy directs the fashion of the community. Here the dependence sinks to the lowest point of servility. We see a proof of it in the spirit of the address. Twenty thousand persons are to get or go without their bread, as a wanton youth, may fancy to wear his shoes with or without straps, or to fasten his straps with strings or with buckles. Can any despotism be more cruel than a situation, in which the existence of thousands depends on one will, and that will on the most slight and fickle of all motives, a mere whim of the imagination. IV. What a contrast is here to the independent situation and manly sentiments of American citizens, who live on their own soil, or whose labour is necessary to its cultivation, or who were occupied in supplying wants, which being founded in solid utility, in comfortable accommodation, or in settled habits, produce a reciprocity of dependence, at once ensuring subsistence, and inspiring a dignified sense of social rights. V. The condition of those who receive employment and bread from the precarious source of fashion and superfluity, is a lesson to nations, as well as to individuals. In proportion as a nation consists of that description of citizens, and depends on external commerce, it is dependent on the consumption and caprice of other nations. If the laws of propriety did not forbid, the manufacturers of Birmingham, Wassal, and Wolverhampton, had as real an interest in supplicating the arbiters of fashion in America, as the patron they have addressed. The dependence in the case of nations is even greater than among individuals of the same nation: for besides the mutability of fashion which is the same in both, the mutability of policy is another source of danger in the former. http://www.constitution.org/jm/jm.htm