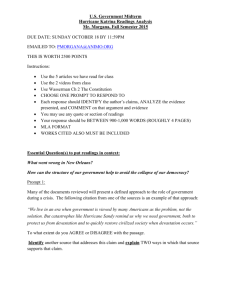

- University of Brighton Repository

advertisement

European Journal of Communication, v.26:3, September 2011 Review: Old and New Media after Katrina, edited by Diane Negra, London: Palgrave McMillan, 2011, 251 pages, ISBN: 9780230102668 The Hurricane Katrina disaster of August 2005, and its aftermath, undeniably and violently disrupted America’s sense of national identity, social progress and constitutional security. ‘Katrina’ has come to signify the storm’s devastation of the American landscape, especially of the city of New Orleans, but it has also come to signify the devastation of foundational and structural myths of American freedom, equality and democracy. Katrina and post-Katrina ‘crisis narratives’, as they appear in various forms of media from television and radio to feature films and the Internet, function both independently and often in concert, to reflect, construct and even reject those disruptions. This fascinating book explores the complex ways in which fictional and factual media representations of Katrina draw upon many anxieties of national infrastructure, welfare, race, and class in contemporary America. The essays here explore wider issues of the ways in which information, entertainment and online media construct disaster narratives and contribute to ‘the organization of public memory’. Foundational images underpin the use of ‘Katrina’ as a synonym for the malfunctioning of democratic and capitalistic government as proven by the administration’s failure to respond to the crisis. Who can forget the image of George W. Bush’s flyover of the devastated states of Louisiana, Alabama and Mississippi on his way back to the Washington rose garden? When the Florida oil spill overwhelmed the Gulf Coast, Barack Obama travelled to the site and held a high-profile press conference – a response that was immediately compared to Bush’s perceived indifference to Katrina’s victims. At the five-year anniversary of the storm, Obama gave an emotive speech at Xavier University, New Orleans, pledging to the citizens that “my administration is going to stand with you, and fight alongside you, until the job is done”. His speech brought into relief many of the perceived differences between the two administrations, especially in terms of social welfare, class and race. It suggested that the great extent of the disaster and suffering could have been, and should have, been prevented by the infrastructure and its administration. Obama called Katrina “a natural disaster but also a man-made catastrophe - a shameful breakdown in government that left countless men and women and children abandoned and alone”. Had Katrina happened on my watch, he implied, it would have been a hell of a lot better for the victims and communities now. Obama then went on to renew his promise to support gulf coast communities after the BP oil spill. Popular far-right commentator Rush Limbaugh gleefully referred to BP oil spill as ‘Obama’s Katrina’ – signifying his belief that the Obama administration had failed itself to respond adequately and left it to BP to clear up the mess, rebuild communities and compensate victims. David Axelrod, a Senior White House adviser to Obama, explained how ‘Katrina’ has become shorthand for ‘governmental incompetence’: “The Katrina analogy suggests that we didn’t or haven’t recognized from the beginning the profound nature of this problem”(cit. USA Today 5/27/2010). The culture industries and citizen media have been pivotal in attempts to salvage, reclaim and reconstruct American national myths from the remnants of traditional ideological, economic and political discourses which had been rent asunder by the disaster. As Negra puts it in her strong and skillful introduction, ‘representations of Hurricane Katrina cannot be read outside of a neo-liberal context marked by “New Economy” market fundamentalism, state-supported assaults on the environment, intense anti-immigration rhetoric [and] the withering role of state care for the vulnerable and various other perversions of democracy that have flourished in recent years’ (1). She criticizes, for example, the ‘appropriation of human suffering’ by neoliberals as well as by those with other political agenda. Even post-9/11, media images during and after the disaster exposed the shocking truth of America’s infrastructural lack of readiness – and possibly its lack of willingness - to cope with a disaster on such a vast scale. Images and narratives of the disaster exposed, for example, the inadequacies of flood defences as well as substandard building and engineering practices. It exposed the weakness of centralized and decentralized power systems and - crucially - the perilous structural inequalities that shakily underpin contemporary American capitalism such as the disowned class system and the unexorcised spectre of racism. The essays in this sharp and forceful collection explore issues such as these as they are represented in, and constructed by, a broad range of factual and fiction images; genres studied include news reportage and National Public Radio, web memorials, TV dramas, nature and ‘geo-porn’ documentaries, and even lifestyle and home-makeover reality shows. The pre-established codes and conventions of genre programming can reassure the public of the reliability of governmental and local agencies by reinstalling myths of infrastructural authority, social provision and risk management. Andrew Goodridge’s essay, for example, explores the ways in which the disaster permitted expression of fears of catastrophe readiness in survival narratives such as the Discovery Channel’s reality-hybrid shows. And the formulaic construction of television dramas are shown to conceal the failure of civil agencies to cope with Katrina; crime genre texts, for example, can be cultural spaces in which a morbid fascination with trauma, death and ‘apocalyptic’ chaos seen at the hurricane site are cathartically expressed with a relatively deflected sense of social and political accountability. Lynsday Steenberg’s essay ‘Uncovering the Bones: Forensic Approaches to Hurricane Katrina on Crime Television’ demonstrates how the use of Katrina in crime narratives was more than merely topical. She argues that the genre’s ‘politically conservative orientation’ actually ‘permits emphasis on “recovery” and “rebuilding” and diminishes emphasis on the immediate duress of the storm, or any underlying sociopolitical circumstances at odds with narratives of recovery’. As such, they ‘facilitate and even encourage such a depoliticized and archaeological treatment of the Katrina event’ (24). Jane Elliot’s essay ‘Life Preservers’ explores the ‘neoliberal enterprise’ of survival narratives in dramas including Trouble In The Water and House M.D., as well as analyzing Spike Lee’s drama on Katrina and racism, When the Levees Broke. Other essays in this collection expose how the shocking failure of the infrastructure to react effectively to the crisis, as well as ‘victim blaming’ responses to the behaviour of some of the stranded citizens as reported in the media, were due in part to the class and ethnicity of the hurricane’s victims. Katrina threatened to devastate the cultural individuality of the city of New Orleans – its ‘exotic’, dark and seemingly unAmerican spice inevitably became catalyst for the violent resurgence of age-old tensions between the founding myth of inclusion and empowerment and the inequalities of race and class. Threats to the cultural and architectural uniqueness that makes New Orleans such a major tourist destination reveal complex discourses at play in the construction of the disaster in the public media sphere. ‘New Orleans’ - as an identity and as a mythic space - is comprised of a special combination of histories, discourse and fantasies including slavery and immigration, dark and glamorous racial Otherness, hedonism and cultural decadence, not to mention antebellum “Southernness”. And New Orleans reconstruction narratives emerge in fictional as well as ‘factual’ media in subtler but equally politicized forms. From the outset, the excavation and rebuilding of towns and cities after Katrina has been a process of media fascination as well as media intervention. Brenda R. Weber’s essay ‘In Desperate Need (of a Makeover): The Neoliberal Project, the Design Expert, and the Post-Katrina Social Body in Distress’ explores how reality TV formats exploit the rebuilding project. In the absence of social housing, reconstruction narratives can afford comfortingly charitable discourses of regeneration, transformation through consumption and a perceived renewal of community and cultural habitus. The reconstruction phase has also been a catalyst for forward-looking campaigners and activists to highlight deep concerns about the relationship between the hurricane, climate change and social welfare. Actor Brad Pitt, for example, initiated the carefully named ‘Make It Right’ project to rebuild the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans. Pitt’s charity pledged to recreate the original community and to validate a bestpractice model of an environmentally friendly, structurally safer and more socially progressive built environment. To qualify for the charity’s ‘Coming Home’ scheme, potential homeowners have to have been living in the area at the time of the Hurricane. The foundation promises to use salvaged and eco friendly materials to create ‘safe, sustainable and affordable homes for working families’ and ‘to be a catalyst for change in the building industry in New Orleans and beyond’ (www.makeitrightnola.org). Both Weber and Negra un-cynically identify such highprofile participation as the ‘celebritization phenomenon’ in which famous media personalities can ‘reinforce the ideological contours of their personae’ (144, n11). As commendable as Make it Right is, Weber argues that Pitt’s project obscures the lack of social welfare provision for survivors because it was initiated by ‘a wealthy philanthropist offering a privatized social welfare’ (183). His celebrity, therefore, attracts donors and promotes sustainable building, but also ‘authorizes and publicizes the neoliberal makeover underway in New Orleans’ (190). Old and New Media after Katrina is an indispensible book for those interested in how to begin to explore the complex convergences of contemporary media, as well as the construction and dispersion of conservative and neo-liberal ideology in mass culture. It goes beyond the high profile news narratives to investigate the reconstructed rhetoric of American democracy in post-Katrina media. Dr Emma Bell, University of Brighton e.j.bell@brighton.ac.uk