Report - MBS Online

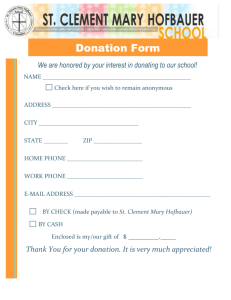

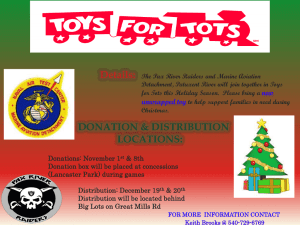

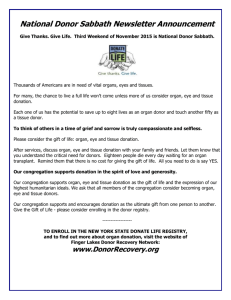

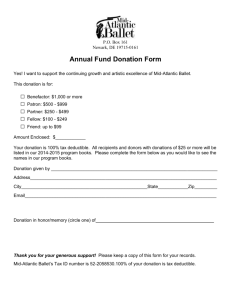

advertisement