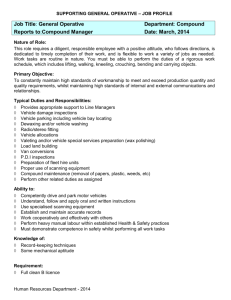

KARTINYERI Richard John - Courts Administration Authority

advertisement

CORONERS ACT, 1975 AS AMENDED SOUTH AUSTRALIA FINDING OF INQUEST An Inquest taken on behalf of our Sovereign Lady the Queen at Adelaide in the State of South Australia, on the 21st, 22nd and 23rd days of February 2005 and the 12th day of April 2005, before Wayne Cromwell Chivell, a Coroner for the said State, concerning the death of Richard John Kartinyeri. I, the said Coroner, find that Richard John Kartinyeri aged 60 years, late of 4 Seymour Street, Tailem Bend, South Australia died at the Flinders Medical Centre, Bedford Park, South Australia on the 27th day of September 2002 as a result of respiratory failure and sepsis complicating acute subdural haematoma. I find that the circumstances of his death were as follows: 1. Introduction 1.1. Richard John Kartinyeri was born on 6 June 1942 at Raukkan on the banks of Lake Alexandrina. Mr Kartinyeri was the defacto husband of Melva Kropinyeri for more than 40 years. He was the father and step-father of nine children, two of whom are deceased. He had been a talented footballer in his youth, and he was a well-known identity in the small town of Tailem Bend. He was described as a competent mechanic, a good fisherman and a good gardener (Exhibit C20a, p1). 1.2. Mr Kartinyeri died on 27 September 2002 as a result of injuries he received on 14 August 2002 when he jumped or fell from a moving vehicle in Railway Terrace at Tailem Bend, and collided with the roadway sustaining severe head and other injuries. 2 1.3. Mr Kartinyeri was a passenger in a vehicle which was being pursued by a police officer because the driver of the vehicle, Allen John Fuss, had committed several traffic offences. 1.4. This incident has been the subject of an extensive investigation by a team led by Inspector Robert Williams at the direction of the Acting Deputy Commissioner of Police, Mr G D Brown. This process is known as a Commissioner’s Inquiry. 1.5. Mr Kartinyeri had not been apprehended, and no form of physical restraint had been placed upon him, and so it could not be said that he had been ‘detained in custody pursuant to an Act or Law of the State’ within the meaning of Sections 12(1)(da) and 14(1)(b) of the Coroners Act 1975 which would render an inquest into his death mandatory. 1.6. A protocol for investigation into deaths in custody developed pursuant to the recommendations of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody includes situations such as the death of Mr Kartinyeri in the sense that his death occurred while police were attempting to detain the occupants of the vehicle in which he was travelling. 1.7. In those circumstances, and having regard to the issues which have arisen in this case, I have deemed an inquest into Mr Kartinyeri’s death ‘necessary’ and ‘desirable’ within the meaning of Section 14(1)(a) of the Coroners Act. 2. Events leading to the fatal incident 2.1. Allen Fuss told me that he had been at the Railway Hotel at Tailem Bend on the evening of 14 August 2002, drinking alcohol. He readily admitted that he was intoxicated (T16). 2.2. While at the hotel, Mr Fuss met and began drinking with Mr Kartinyeri and two of his step-daughters, and they later adjourned to the Kartinyeri residence in Tailem Bend. 2.3. The statement of Maria Kropinyeri, one of Mr Kartinyeri’s step-daughters, indicates that Mr Kartinyeri and Mr Fuss had only met each other that evening (Exhibit C11a, p3). At one stage during the evening, Mr Fuss drove her, her friend and her niece home from the hotel. 3 2.4. Ms Kropinyeri said that she was also drunk that evening, and that: 'We went into the house and we all sat down drinking and then my father needed a packet of cigarettes and that’s when it all happened.' (Exhibit C11a, p7) 2.5. At a stage earlier than the final journey, Mr Fuss drove Mr Kartinyeri to the hotel to buy some beer. Mr Fuss explained that he had been banned from the Riverside Hotel as a result of an earlier incident, so Mr Kartinyeri went in and bought the alcohol. 2.6. Mr Jason Edwards, a Bar Person at the Riverside Hotel, described what happened in his statement: 'At about 9:00pm on Wednesday the 14th of August 2002, I was in the front bar of the hotel, which fronts onto Princes Highway. I saw headlights travelling toward the hotel from North Terrace at the T junction with Princes Highway. The vehicle travelled across Princes Highway, over the lawn dividing strip which separated Princes Highway and the hotel car park and then across the car park and stopped. I recognised the vehicle as a blue F100, Ford utility which belonged to Allen Fuss, a local man. The car park was well lit and I could see the driver of the utility was Allen Fuss. He appeared to be drinking from something in his right hand. The front seat passenger was Richard Kartinyeri. Kartinyeri got out, walked to the bottle shop and returned to the utility with a carton of Victoria Bitter stubbies and got back into the front passenger seat of the utility. The utility reversed about 5 to 7 metres, then drove up the kerb onto the lawn area. The utility accelerated hard causing the rear of the vehicle to ‘fishtail’ to the left as the vehicle started going sideways. It drove onto the lawn and then around the bench onto the car park before driving straight over the kerb again onto Princes Highway and along North Terrace.' (Exhibit C6, pp1-2) 2.7. Mr Edwards reported the matter to the police and Senior Constable George Fox of the Tailem Bend Police Station was tasked to attend and investigate. 2.8. Senior Constable Fox attended at the Riverside Hotel and spoke to Mr Edwards and took a statement from him. At about 9:30pm, as he was driving away from the hotel on North Terrace, he saw a blue Ford F100 pass him in the opposite direction. He performed a U-turn and followed the F100 through the rear of the Shell Roadhouse and the back of the hotel and on to Murray Street to travel east. He activated the red and blue flashing lights and advised Murray Bridge by radio that he was commencing pursuit. 4 2.9. Senior Constable Fox followed the vehicle along Murray Street at speeds up to 90 kilometres per hour through several intersections. He then turned left into South Terrace and then left again into Railway Terrace to travel west. He was ‘calling the chase’ over the radio and requesting backup. He said: 'I was aware that a traffic patrol, Hills 026, Geoff Capper, was in the area. I’d seen him on three occasions, say an hour or 45 minutes prior to this.' (Exhibit C24, p5) 2.10. On Railway Terrace, Senior Constable Fox saw the following: 'I saw something come from the vehicle … On First seeing it I just sort of believed that something may have come out of the back of the vehicle. I looked- My first thought was a branch of a tree for some reason, it was just a dark sort of shape, … just something come out from the vehicle. Seeing that fall to the road I moved over to the right of, of its location so I wouldn’t collide with it. On nearing it and within my headlights and at this stage I suppose I’m travelling about 60 kmh like the speed of that vehicle would’ve been at that time, at that location, that point of time. I then saw a male person roll on to the road, all right, and my thought was, immediately then, was either I stop or continue.' (Exhibit C24, pp5-6) 2.11. Senior Constable Fox said that he radioed in and advised of what he had seen and continued pursuing the vehicle. He requested the attendance of an ambulance. He again called for assistance to ascertain where Hills 026 was. 2.12. Senior Constable Fox said that as he passed the Riverside Hotel on Railway Terrace, he crossed North Terrace at speeds of up to 120 kilometres per hour while following the F100. The Ford then turned left into Tenth Street and then left again on to the access road to the Princes Highway to travel back in an easterly direction. He said: 'On doing so the rear of the vehicle has broken loose. I could see in my headlights the rear wheels of his vehicle spinning rapidly and the vehicle has fishtailed around to the right. He’s gone partly up on to a, the kerbing, or the lawn area … such that his headlights was pointing directly at me. I thought at this stage that he may ram me. I then moved to the right to be off the road on to the right side of the road, give him passage to, to go past me so he wouldn’t ram me. He’s then gone up on to the kerbing, the lawn area, and then continued to travel on the Princes Highway access road in a west direction.' (Exhibit C24, p8) 2.13. The driver of the Ford F100 applied the brakes and then turned left on to the Princes Highway, and then at a crossover turned right to travel west on the Princes Highway towards Murray Bridge. However, after travelling only a short distance he applied the brakes again, and then performed a U-turn at another crossover and travelled east 5 back towards Tailem Bend. Upon entering the town, he slowed and turned left onto the access road again, by this time travelling at only 30 kilometres per hour or so, and eventually drove to and stopped at the Police Station. Senior Constable Fox said the driver was remorseful and apologised for his actions (Exhibit C24, p9). Mr Fuss was arrested and taken into custody. 2.14. The first person to find Mr Kartinyeri on the roadway was Ms Pasqualina Ullucci, who was passing in her car. She drove to the police station just as Senior Constable Fox followed Mr Fuss into the carpark and proceeded to arrest him. She told Senior Constable Fox about a body in Railway Terrace. Senior Constable Fox told her that an ambulance had already been called. She then returned to the scene to prevent another accident. By this time another member of the public was also there, and the ambulance arrived at around the same time (Exhibit C12a, p2). 2.15. In the meantime, Senior Constable Capper had reached Tailem Bend and had driven along Railway Terrace and found Mr Kartinyeri lying in the middle of the southbound side of the road. He positioned his vehicle across the road and made a further call for the attendance of an ambulance. He noted that Mr Kartinyeri was breathing very heavily and did not respond to questions. He noted bleeding slightly from the mouth, a strong smell of liquor, a large amount of ‘clear fluid not blood’ extending from the head of the person to the kerb (Exhibit C22a, p2). 2.16. Senior Constable Capper said that within a minute or so of his arrival an ambulance arrived and began attending to Mr Kartinyeri. 2.17. Senior Constable Capper noted the remains of a broken beer bottle in the centre of the road just north of where Mr Kartinyeri had been lying. He also noted a large wet patch about 2 metres long and about 500mm wide running down the centre of the road (Exhibit C22a, p2). 2.18. Mr Kartinyeri was taken by ambulance to Tailem Bend Hospital. What transpired from there has been summarised by Dr J D Gilbert, the Forensic Pathologist who performed the post-mortem examination of Mr Kartinyeri’s body. Dr Gilbert’s report reads as follows: 'The deceased was reportedly a front seat passenger in a vehicle involved in a police pursuit at Tailem Bend on the night of 14 August 2002. He had a past history of rightsided rib and scapular fractures, hypertension, alcohol abuse and emphysema. 6 He exited the vehicle while it was in motion and was found lying on the road. He was initially assessed at Tailem Bend Hospital and was found to be unconscious (GCS 3) with poor respiratory effort and with blood in the airways. He had a right periorbital haematoma and was bleeding from the mouth and nose. He was retrieved to Flinders Medical Centre where a CT scan of the head showed a large right-sided acute subdural haematoma, right frontal, parietal and temporal lobe contusions and right temporal and occipital skull fractures. He was taken to theatre for urgent evacuation of the subdural haematoma. Immediately postoperatively, his intracranial pressure was satisfactory but shortly thereafter it began to rise and a repeat CT scan showed enlargement of the right-sided parenchymal contusions. This did not initially respond to medical measures and some herniation of the brain through the craniotomy defect was noted. He was returned to theatre where the bone flap was removed, a right temporal lobectomy was performed and a postoperative subgaleal haematoma was evacuated. He was managed subsequently in the Critical Care Unit. By 18 August, the intracranial pressure had moderated. Over the next few days, it was apparent that he had ARDS changes in both lungs and, when not sedated, withdrawal to a painful stimulus was noted. Episodic hypertension was noted and treated with clonidine and captopril. By 26 August eye opening to a painful stimulus was demonstrated and there were spontaneous movements of all limbs except the left arm. He remained ventilator dependent however. By 2 September his overall neurological outlook was considered ‘very poor’. On 6 September he was discharged from the Critical Care Unit. A CT scan on 9 September showed a left-sided hygroma (chronic subdural collection) that was evacuated via a burrhole the following day. Additional hygroma fluid (approximately 70 mLs) was aspirated via the burrhole on 20 September. A left chest drain was inserted on 22 September following oxygen desaturation associated with low-grade fever and radiological evidence of ongoing left lower lobe consolidation and a left pneumothorax. A chest tube was inserted and immediately drained air through an underwater seal drain. On 26 September subcutaneous emphysema of the chest and respiratory failure were noted. The deceased’s family was notified. He was then treated with morphine for comfort care and atropine to reduce his respiratory secretions. At 1900 hours that day he had a large vomit and was thought to have aspirated vomitus via his tracheostomy. He was febrile, tachycardic, hypertensive and tachypnoeic with worsening surgical emphysema. He was certified dead at 0045 hours 27 September.' (Exhibit C3a, pp4-5) 3. Cause of death 3.1. A post-mortem examination of the body of the deceased was performed by Dr Gilbert on 30 September 2002 at the Forensic Science Centre. Following his examination, he concluded that the cause of death was: 'Respiratory failure and sepsis complicating acute subdural haematoma.' (Exhibit C3a, p1) 7 3.2. Dr Gilbert commented: 'Death has been attributed to respiratory failure and sepsis complicating prolonged mechanical ventilation following treatment for a large right-sided acute subdural haematoma resulting from blunt head trauma due to a fall from a moving motor vehicle approximately 6 weeks prior to death.' (Exhibit C3a, p4) 3.3. A neuropathological assessment was performed by Professor P C Blumbergs at the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science. Professor Blumbergs’ detailed examination of the brain disclosed the following injuries: '1. Compression deformity of right cerebral hemisphere consistent with decompressive craniotomy. 2. Patchy haemosiderin staining of leptomeninges consistent with old subarachnoid haemorrhage. 3. Cystic necrosis of right temporal lobe. 4. Cystic necrosis of left temporal lobe. 5. Evidence of previous episode of raised intracranial pressure with subfalcine herniation and cortical necrosis in the anterior cerebral artery territories (bilateral), focal infarction of the corpus callosum and infarction in right posterior cerebral artery territory. 6. Swelling of left cerebral hemisphere with evidence of disruption of the rostral brain stem by multiple recent secondary haemorrhages. 7. Evidence of old subdural haemorrhage ' (Exhibit C4a, p2) 3.4. A microscopic examination of the brain produced similar findings (see Exhibit C4b). 3.5. Unfortunately, due to the transfer of Mr Kartinyeri between hospitals and the general urgency of the situation, a blood sample was not taken prior to his death pursuant to the provisions of the Road Traffic Act. Accordingly, it has not been possible to determine whether, and to what extent, Mr Kartinyeri had consumed alcohol and was affected by it at the time he fell from the vehicle. 3.6. I accept Dr Gilbert’s conclusions concerning the cause of death, and find that it was respiratory failure and sepsis complicating acute subdural haematoma. 3.7. When Dr Gilbert gave oral evidence, he told me that the injury most urgently in need of treatment was the subdural haematoma. This injury gives rise to an immediate 8 need for surgical intervention in the form of a craniotomy so that any pressure being applied to the brain by the haematoma can be relieved. 3.8. Dr Gilbert said that the evidence from the ambulance records and the clinical record at Flinders Medical Centre indicates that Mr Kartinyeri was urgently evacuated firstly to Tailem Bend Hospital, and then to Flinders Medical Centre where he immediately underwent an operation. He later developed cerebral contusions requiring further surgery, which was carried out without delay. Dr Gilbert said that, in his opinion, the treatment given to Mr Kartinyeri was both appropriate and timely (T151). 3.9. Unfortunately, the pressure which had already been applied to Mr Kartinyeri’s brain prior to the surgery was such that he remained unconscious and required mechanical ventilation which led to pneumonia and to his eventual death. Dr Gilbert said that in those circumstances, Mr Kartinyeri had no prospect of recovery, and that there was nothing that either the police officers or the ambulance officers could have done at the scene which would have changed the outcome. Mr Kartinyeri was breathing spontaneously and adequately and his blood pressure and pulse were both adequate at the scene, so he was not in need of resuscitation at that time (T150-T151). 4. Issues arising at inquest 4.1. Why did Richard Kartinyeri exit the vehicle? The evidence is clear that Mr Fuss was driving his vehicle erratically and dangerously. He did not dispute Senior Constable Fox’s evidence that he drove at about 60 kilometres per hour down Murray Street through two spoon drains causing the vehicle to pitch violently, and that he disregarded two give way signs. He then made left turns into South Terrace and then into Railway Terrace at a fast speed and then travelled about 90 metres along Railway Terrace before Mr Kartinyeri exited the vehicle. Having regard to the position of Mr Kartinyeri’s body on the roadway (across the northbound carriageway of Railway Terrace), it is likely that the vehicle was on the incorrect side of the road at the time he exited. 4.2. Mr Charles, counsel for several of Mr Kartinyeri’s family members, pointed to the family statement (Exhibit C20a) and in particular their statements that Richard Kartinyeri was scared of driving in motor vehicles, particularly when they were being driven fast. He submitted that Mr Kartinyeri must have been ‘terrified’ by Mr Fuss’ driving and that this was why he panicked and exited the vehicle. 9 4.3. While I understand the force of that submission, it is difficult to reconcile with the fact that Mr Kartinyeri undertook two journeys with Mr Fuss that night, the initial one to the Riverside Hotel when they were seen by Mr Edwards, during which Mr Fuss was driving so erratically that Mr Edwards called the police, and the second journey when they were driving to the Roadhouse to get cigarettes and when they were pursued by Senior Constable Fox. If Mr Kartinyeri was terrified of Mr Fuss’ driving, it is difficult to understand why he might have got into the car a second time. 4.4. It is not known whether Mr Kartinyeri was intoxicated by alcohol that evening. Maria Kropinyeri said that her step-father was ‘not really drunk’ (Exhibit C11a, p10). Ms Melva Kropinyeri said that he had a couple of stubbies of beer that night and was ‘not seriously intoxicated’ (Exhibit C20a, p2). 4.5. Senior Constable Capper said that he detected a strong smell of liquor about Mr Kartinyeri’s person when he first arrived at the scene, but pointed out that there was a broken beer bottle in the centre of the road just north of where he was lying, and a large wet patch in the vicinity which could have accounted for the smell (Exhibit C22a, p2). 4.6. There was an allegation in Maria Kropinyeri’s statement which is, as far as I can tell, third hand hearsay, that the passenger door on Mr Fuss’ F100 was faulty, giving rise to the suggestion that Mr Kartinyeri may have fallen out of the vehicle accidentally (Exhibit C11a, p6). 4.7. This was checked thoroughly by the Police Mechanic, Christopher Graham, who found: 'The left door was springy when closed, however the door did lock. The left door opened from the inside.' (Exhibit C15a, p7) 4.8. Mr Graham also commented that the front left seatbelt was retracted when he examined it, and that the ‘nail tongue would lock to the stalk and hold’ (ibid). 4.9. Mr Fuss gave oral evidence and I agree with Mr Charles’ comment that he was an unsatisfactory witness. His evidence vacillated between denials and claims that he was unable to remember on the basis of his intoxication. He did tell me that Mr 10 Kartinyeri said words to the effect of ‘I’m out’ or ‘I’m jumping out’ before he opened the door and was gone (T38). 4.10. On the basis of the above evidence, I think it is appropriate to exclude accident on the balance of probabilities. If Mr Kartinyeri had exited while the vehicle was negotiating a right turn at speed, accident might be more feasible. However, the vehicle was being driven in basically a straight line. That, added to Mr Fuss’ evidence, to which I am unwilling to give great weight, makes a finding of a deliberate action on Mr Kartinyeri’s part more likely. 4.11. It is impossible to know what motivated Mr Kartinyeri to exit the vehicle when he did. The evidence of Senior Constable Fox was that the vehicle was travelling at about 60 kilometres per hour when he exited. It is possible that he had some sort of panic attack. It is also possible that he was more severely intoxicated than the evidence presently suggests. A further possibility is that both of these factors may have played a part. In either event, I am in no doubt that Mr Kartinyeri’s actions, extreme and unpredictable as they were, were prompted by Mr Fuss’ dangerous and irresponsible driving. 4.12. Urgent Duty Driving This is another case involving what is described in South Australia Police (‘SAPOL’) General Orders as ‘Urgent Duty Driving’. I have discussed the issues herein previously in my findings in relation to the deaths of Brenton Maurice Goldsmith in May 2001 (Inquest 17/2003), and Tyson Matthew Charles Lindsay in February 2001 (Inquest 15/2004). 4.13. I set out the relevant General Order (210/01) in Goldsmith as follows: '6.1 When you use the exemption provided in Rule 305 of the Australian Road Rules in responding to taskings or driving in a manner which, when compared to normal risks, substantially increases the risk of injury to police, the public or suspects, or of damage to property, the driving will be considered urgent duty driving. In all urgent duty driving situations SAPOL’s operational safety philosophy and principles must be applied. Safety must be the primary concern ahead of capture. Urgent duty driving is an area of great potential risk for loss of life, injury or damage to property. In all urgent duty driving situations: The urgent duty driving should not be disproportionate to the circumstances. 11 Risk must be continually assessed in terms of the potential danger to all and the risk of damage to property. Police have a duty of care not to endanger other road users and must exercise effective command and control. Occupational health, safety and welfare requirements must be met. The driver of the vehicle must be responsible for their actions. The senior member may be held accountable for the actions of the driver. You should consider helicopter assistance as the preferred option.' (Exhibit C73) 6.2 The General Order sets out what should be done when a direction is given to terminate urgent duty driving as follows: 'Terminate – immediately slowing the police vehicle and complying with the area speed limit and the other traffic requirements, turning off all emergency warning equipment, and resuming patrol'. (Exhibit C73) 6.3 The policy governing urgent duty driving is stated as follows: 'Policy Urgent duty driving may only be undertaken: in response to an emergency involving obvious danger to human life; or when the seriousness of the crime warrants it. In all cases the known reasons for the urgent duty driving must justify the risk involved.' (Exhibit C73) 6.4 The ‘Considerations for Institution/Continuation’ are stated to be as follows: Before commencing and while engaged in urgent duty driving the senior member and the driver must consider: the seriousness of the emergency or crime; the degree of risk to the lives or property of police, the public or the suspect/s; whether the driver holds the appropriate driving permit; whether immediate apprehension is necessary (if in pursuit); the availability of other police assistance; the capability and type of police vehicle or forthcoming assistance; the practicability of using other stopping devices such as road spikes; environmental and climatic conditions; police driver competence and local knowledge. 12 If the urgent duty driving involves a pursuit it must be terminated when: the necessity to immediately apprehend is outweighed by obvious dangers to police, the public or the suspects if the pursuit is continued; or the apprehension can be safely effected later (eg, the identity of the owner/occupants of the vehicle is known) instructed by supervisor, State Duty Officer of Communications Senior Sergeant. If the urgent duty driving involves an emergency response it must be terminated when the necessity to attend urgently is outweighed by obvious dangers to police or the public.’ (Exhibit C73) 6.5 The Orders regarding additional vehicles joining a situation of urgent duty driving are as follows: 'If the urgent duty driving involves the pursuit of a vehicle there is to be only one primary vehicle and one backup vehicle. No other police vehicle shall become involved in the pursuit unless directed by the member responsible for controlling and coordinating the situation. If the urgent duty driving involves an emergency response there is to be only one first attendance vehicle unless directed by the member responsible for controlling and coordinating the situation.' (Exhibit C73) 6.6 The Orders regarding ‘Unmarked Police Vehicles’ taking part in urgent duty driving include the following: 'A police vehicle which: is not fitted with emergency equipment and markings; is a prisoner escort vehicle; or is a station wagon or utility; and is engaged in urgent duty driving involving a pursuit, must be replaced, as soon as possible, by a police vehicle (other than a motorcycle) fitted with emergency equipment and markings. Unmarked police vehicles should not be engaged in any urgent duty driving situations unless exceptional circumstances exist. (Exhibit C73)' 4.14. In his report, Inspector Williams summarised, correctly in my view, Senior Constable Fox’s decision to initiate the pursuit of Mr Fuss’ vehicle as follows: ' At that time he did not know who the driver was although he had been given a name earlier and suspected the driver was Fuss. He was not aware that Fuss was in possession of a Ford F100 utility. 13 He was aware of at least 2 Ford F100 utilities in Tailem Bend. He did not have a registration number to identify the vehicle and possible driver. He suspected the driver was intoxicated (based on the earlier statement and behaviour). The manner of driving gave him the opinion that there was ‘something else bizarre in relation to his driving’. He also felt that the driver was a danger both to himself and other members of the public and needed to be stopped.' (Exhibit C26, p19) 4.15. As to whether Senior Constable Fox should have terminated the pursuit after he saw the male person rolling on the road, Inspector Williams summarised Senior Constable Fox’s position as follows: ' Should he continue the chase as he hadn’t any proof as to who the driver was. He hadn’t at that stage been able to obtain a registration number to confirm the identity of the vehicle for future follow up. He wasn’t sure at the time that he first saw the object fall from the vehicle that it may have been a person. He initially thought it may have been a log. He also thought it may have been the driver of the vehicle attempting to flee and expected the Ford F100 to stop just down the road. When he travelled past Mr Kartinyeri and identified that it was in fact a person he didn’t know how seriously the person was injured and thought that the person may just get up and run away. He believed that Hills 026 S/C Capper was in the close proximity and would immediately assist.' (Exhibit C26, p20) 4.16. Inspector Williams made the following analysis of Senior Constable Fox’s actions: 'It must be stressed that at the time when Mr Kartinyeri alighted from the Ford F100, S/C Fox had just executed a left turn onto Railway Terrace. The above incident occurred on a relatively dark stretch of road. Both the offending vehicle and S/C Fox’s police car were in the process of accelerating and S/C Fox would not have expected an incident like this to occur. His thought processes as listed above would have been over a span of several seconds. His decision to continue the pursuit was based on his belief that S/C Capper was only moments away (less than 1 minute). Whilst it has been proven that S/C Capper was a reasonable distance away and in fact took approximately 5:24 minutes to arrive on scene after the initial commencement of the pursuit, it was clear in S/C Fox’s mind that he was much closer than this. S/C Capper at no stage gave a clear indication as to his actual location or the length of time he would expect to take to get to the scene. This has a major bearing on the decision to terminate or continue with the pursuit.' (Exhibit C26, p20) 14 4.17. Senior Constable Fox told me that if he had been aware that the male person on the roadway was Mr Kartinyeri, whom he knew well and whom he liked and towards whom he had acted compassionately in the past, he would have terminated the pursuit (T132). I accept his evidence about that, although I find his position strange in that his decision to stop or not should not have been determined by whether the man was known to him or not. 4.18. Further, Senior Constable Fox told me that if he had been aware that Senior Constable Capper was more than 5 minutes away from the scene, rather than less than 1 minute away, he also would have terminated the pursuit (T143-T144). I accept his evidence on that issue as well. 4.19. There was clearly a misunderstanding between Senior Constable Fox and Senior Constable Capper as to each other’s movements that evening. Capper said in his statement that he advised Murray Bridge of his location after he heard that the Tailem Bend patrol was trying to stop a vehicle in Tailem Bend (Exhibit C22a, p1). Clearly, this call occurred before Constable Marnane, who was the Radio Operator at Murray Bridge, commenced recording radio transmissions. Neither Capper nor Fox could recall precisely what Capper said about his location. The transcript, part of Exhibit C26, is replete with confusing statements about the position of the vehicles and where they were in relation to both the high-speed pursuit and the injured person on the roadway. 4.20. Inspector Williams calculated that Senior Constable Capper did not reach Mr Kartinyeri until somewhere between 5 minutes and 24 seconds and 5 minutes and 54 seconds after the pursuit commenced. If Mr Kartinyeri exited Mr Fuss’ vehicle about 40 seconds after the chase commenced, then he was lying on the roadway for between 4 minutes 44 seconds and 5 minutes 14 seconds. 4.21. Conclusions Having regard to the considerations set out in Inspector Williams’ report quoted above, I conclude that Senior Constable Fox’s decision to pursue Mr Fuss’ vehicle was justified. I am somewhat mystified by Senior Constable Fox’s decision to continue the pursuit after he saw a male person had fallen from the vehicle. However, the decision was taken in a split-second, in circumstances where he believed that his colleague was in the near vicinity and would be able to render assistance. He immediately called an ambulance. Even if he had stopped, there was nothing that he 15 could have done to prevent Mr Kartinyeri’s death having regard to the terribly injury he had sustained. In all those circumstances, I do not criticise Senior Constable Fox for his decision to continue the pursuit. 4.22. Supervision Senior Constable Colin Rohde was, at the time, a designated Shift Manager at the Murray Bridge Police Station. He relieved Sergeant Ninnis for two periods of three weeks at around this time. The question arose whether he had adequately discharged his duty as Shift Manager in relation to his non-intervention in the urgent duty driving of Senior Constable Fox. When asked about his role, he said: 'Just the responsibility for any taskings in the Murray Bridge area, to manage anything in that nature. (Exhibit C23, p3) 4.23. Later, he was asked: 'Did you believe that as Shift Manager for Murray Bridge, that you had any responsibility in the management and control of what was, of that high speed, of that pursuit? A: Not for Tailem Bend, no.' (Exhibit C23, p9) 4.24. Inspector Williams pointed out that Senior Constable Rohde’s attitude was in direct conflict with Policy Statement 11, issued on 10 May 2002 by Superintendent T G Rienets, the Superintendent in Charge of the Hills Murray Local Service Area (‘LSA’). Included in that statement, are the following passages: 'The Shift Manager has the delegated authority of the Officer in Charge of the LSA to use all resources within the LSA. … Shift Managers will be responsible for achieving best practice in service delivery through: Monitoring SAPOL Communications and the tasking workload for the entire LSA. Liaising with supervisors from all Sections within the LSA … … Where appropriate perform the role of Police Forward Commander. … Liaising with the State Duty Officer when required. …' (Exhibit C19d, p2) 16 4.25. The clear import of this Policy Statement is that the responsibility of the Shift Manager covered the entire LSA, not merely Murray Bridge. Surprisingly, Senior Constable Rohde told me that he had never seen the document prior to coming to court (T77). He added that even if he had seen the Policy Statement, he would not have done anything differently on the night, and would have left it to the discretion of Senior Constable Fox who was an experienced and cautious police officer (T76). 4.26. The role of a Supervisor in an urgent duty driving scenario is a vital one. A principal responsibility of the Supervisor is to ascertain sufficient information from the pursuing officer so that the Supervisor may form an independent and dispassionate judgment about whether the pursuit should be discontinued. It is obvious that Senior Constable Rohde did not seek out the requisite information to discharge this function. 4.27. Having said that, however, it is extremely unlikely that even the most assiduous Supervisor would have intervened in the 40 seconds between the commencement of the pursuit and when Mr Kartinyeri exited Mr Fuss’ vehicle. 4.28. If such an event were to occur now, all of these radio transmissions would have been digitally recorded on the Government Radio Network (‘GRN’) and monitored not only by a Radio Operator in Murray Bridge, but also by staff in the Communications Centre in Adelaide and by the State Duty Officer, a Commissioned Officer. Such officers are well trained in the supervision and management of urgent duty driving situations, and would exercise the relevant discretion in such a case. 4.29. Conclusions While Senior Constable Rhode failed to exercise any supervision of Senior Constable Fox’s actions, I accept that he was unaware of his duty to do so outside the Murray Bridge area. He was relieving another officer at the time, and it appears that the relevant Policy Statement had not come to his attention, which needs to be addressed by SAPOL management at the Hills Murray LSA. 5. Recommendations 5.1. Inspector Williams made the following recommendations in his report: '1. Hills Murray LSA reinforce Policy Statement #11 – shift managers with all staff, particularly in relation to areas of responsibility. 17 2. Murray Bridge Police reinforce the policy for recording operations of significance and ensure the equipment is in a constant state of readiness. 3. No action be taken against S/C Fox in relation to failing to immediately stop after a collision. 4. SAPOL consider implementing training for officers tasked with managing critical incidents, particularly country officers who staff the communications network. 5. Mr Kartinyeri died on the evening of 26 September 2002, therefore consideration should be given to having Major Crime Investigation Branch and O/C IIB review this process in line with General Orders and Deaths in Police Custody guidelines.' (Exhibit C26, p43) 5.2. I agree with those recommendations. In view of the finding I have made, I make no further recommendations pursuant to Section 25(2) of the Coroners Act, 1975. Key Words: Death in Custody; Police (pursuit); Urgent Duty Driving; Intoxication In witness whereof the said Coroner has hereunto set and subscribed his hand and Seal the 12th day of April, 2005. Coroner Inquest Number 5/2005 (2704/2002)