An Empirical Study of the Consumer Choice

Division of Economics

A.J. Palumbo School of Business

Duquesne University

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF THE CONSUMER CHOICE PROCESS

IN A MONOPOLISTICALLY COMPETITIVE ENVIRONMENT

Maria L. Sciandra

Submitted to the Economics Faculty

In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Bachelor of Science in Business Administration

December 2008

1

Faculty Advisor Signature Page

Antony Davies, Ph.D. Date

Associate Professor of Economics

2

AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF THE CONSUMER CHOICE PROCESS IN A

MONOPOLISTICALLY COMPETITIVE ENVIRONMENT

Maria Sciandra

Duquesne University

December 2008

The stream of behavioral literature on consumer choice spans more than twenty years, and identifies a range of behaviors collectively known as context effects. Davies and Cline (2005) proposed a theoretical framework to unify the observed context effects as manifestations of a single set of behavioral propositions. In this study, I will employ a series of controlled experiments to test these behavioral propositions. The propositions describe heuristics that consumers use to maximize the likelihood of selecting an optimal brand in the presence of incomplete and costly information.

3

Table of Contents

4

1. Introduction

At a single point in time, a monopolistically competitive market is made up of a large population of brands, each with different set of salient attributes. Over time, individual brands appear and disappear, and extant brands’ attributes change. It is against the background of this large and varying set of information that the consumer must choose a single brand. Given that it would be impossible for any consumer to gather all information on all possible brands in a given market, the consumer is forced to make the best selection possible based on incomplete information. At one extreme, the consumer could simply select the first brand she sees, incurring no information cost yet suffering from a larger probability of selecting a suboptimal brand. At the other extreme, the consumer could spend an infinite amount of time searching for the best brand, thereby incurring infinite information cost yet reducing the probability of selecting a suboptimal brand to zero. In an attempt to improve the probability of selecting the best brand, while minimizing the cost of obtaining information, consumers rely on heuristics to aid their decision making.

Consumers use a phased decision making process when selecting a brand

(Bettman, 1979). This is an iterative process which involves three distinct stages: product-market perception, consideration, and choice . Product-market perception is the mental positioning of brands based upon the consumer’s past experience in the market.

During this stage, the consumer has evaluated each brand on their salient attributes.

It is important to understand that the product-market perception stage is based on incomplete information and imperfect experience. Davies and Cline (2005) define the true brand universe be the positioning of all existing brands according to their true (as

5

opposed to perceived) attributes. Because consumers are unable to gather complete information they will never observe the true brand universe. Consumers’ product-market perception phase creates estimated brand universes based on available information.

Estimated brand universes differ from the true brand universe due to a number of possible external uncertainties. Consumers may only have partial information, in which they are unaware of all the brands which exist in the true brand universe. Consumers may also have inaccurately measured an attribute, or even be unaware of one or more attributes.

Lastly, the consumer may be unable to update their estimated brand universe as quickly as the market changes.

The utility a consumer derives from consuming a brand is defined by the consumer’s true utility function (Davies and Cline, 2005). Consumers do not experience their true utility function because it is impossible to obtain an experience with all attributes of all brands, and instead make their purchasing decision based on their estimated utility functions . Estimated utility functions differ from true utility functions due to any number of internal uncertainties. Consumers may be unsure of the consequences of their purchase, or unsure of the influence each attribute will have on their utilities. In the product-market perception phase the consumer attempts to generate an estimated brand universe, and an estimated utility function based only on available information, and past experience.

Given product-market perception, the consumer begins the consideration stage.

The consumer uses a non-compensatory screening method to form a consideration set

(Bettman 1979) from among the perceived brands. Such a strategy is implemented to reduce the number of alternatives quickly, and with very little cognitive effort. This is

6

done by eliminating brands from the market based on one or more key attributes regardless of other attributes (Biehal and Chakravarti, 1986). 1 Finally, given the consideration set, the consumer uses a compensatory strategy to arrive at a final choice.

Because the consideration phase reduced the choice alternatives to a manageable amount, the consumer is able to implement such a strategy to trade-off one attribute for another to arrive at a choice.

The consumer decision making strategy is an iterative process. Through the information and experience gained from consumption, consumers may realize they have poorly estimated the brand universe and/or their utility functions. Consumers then reevaluate their estimated brand universes and estimated utility functions in an ongoing process to reduce the deviations from the true brand universe and their true utility functions (Davies and Cline, 2005).

To minimize uncertainty, as well as increase information processing and cognitive stability, consumers divide their estimated brand universe into “clusters”-groups of brands perceived to have similar attributes. During the consideration stage of the choice process, consumers select one cluster from among all competing clusters, while ultimately choosing a single brand from the considered cluster during the choice stage.

Davies and Cline (2005) identify three characteristics of the consumer’s estimated brand universe which are used in constructing heuristics: cluster size, cluster variance, and cluster frontier.

Cluster size is the number of brands a consumer mentally groups into a single cluster. An increase in cluster size may affect the consumer’s consideration phases by

1 For example, a consumer might immediately split the housing market based on number of bedrooms, and consider only two-bedroom houses.

7

decreasing uncertainties. A large cluster may reduce external uncertainty by implying that the consumer is observing a larger portion of the true brand universe. A large cluster size may also reduce internal uncertainty because observing a higher number of brands implies a greater demand, which gives the consumer a sense of affirmation by other consumers. Therefore, an increase in cluster size will cause an increase in the probability of consideration for brands in that cluster.

Cluster variance is the perceived distribution of brands around the center of the cluster

2

. Greater cluster variance implies greater consumer uncertainties. Large cluster variance increases external uncertainties by implying that there may be brands within the cluster the consumer is unaware, or perhaps that the consumer has incorrectly grouped brands into the same cluster. A consumer may also gain greater internal uncertainty due to doubt regarding the consequences of a purchase, and estimations of attributes within the cluster. Thus, high cluster variance causes it to be less attractive, resulting in a decrease in the probability of consideration for brands in that cluster.

The cluster frontier

, or the “ideal point,” is the best possible combination of attributes from perceived brands within a cluster. Such combinations may not exist in the market, and consumers will mentally form additional unobserved brands through a process called brand extrapolation. A consumer may believe that, because of technological constraints, certain combinations of attribute level cannot be attained (e.g., an 8-cylinder SUV that gets 40 mpg). The probability of a consumer choosing a brand,

2 The measure for variance defined by Davies and Cline (2005) implicitly assumes the two attributes have the same scale. I have redefined cluster variance as follows

n k

is the adjusted attribute

n k

such that:

n k

k min( max(

1 n n

n k

1

n

k

)

min(

)

n

1 n

n k )

Cluster variance is then:

1

NK

n K

1 k

1

(

n k n c

)

2

8

given that the consumer is considering the brands cluster, increases as the perceived distance between the brand and the cluster frontier decreases.

The probability of choice for a given brand is therefore correctly measured by the probability of consideration for that brand multiplied by the probability of choice-givenconsideration. An increase in either Pr(Consideration) or Pr(Choice|Consideration) will result in an overall increase in Pr(Choice), ceteris paribus .

Using inductive reasoning, Davies and Cline drew on empirical studies from the context effects literature to propose their behavioral propositions. While their propositions can explain all of the context effects that have been observed in the literature, their explanation is ex post. To date, there has been no formal test of their propositions. The purpose of this paper is to formally test Davies and Cline’s propositions as related to the effects of cluster size, cluster variance, and perceived distance to the cluster frontier on the probabilities of choice and choice-given-consideration. The method is to examine consumer choice through a controlled experiment. The study will empirically provide evidence for three propositions made by Davies and Cline: 1.) The probability of a consumer considering brands within a given cluster increases as the perceived size of the cluster increases, ceteris paribus. 2.) The probability of a consumer considering brands within a given cluster decreases as the perceived variance of the cluster increases. 3.) The probability of a consumer choosing a brand, given that the consumer is considering the brands cluster, decreases as the perceived distance between the brand and the cluster frontier increases.

9

2. Literature Review

There exists a great deal of work on consumer choice in the presence of brands within consumer behavior literatures.

3

The method by which consumers organize alternatives in their perceived market, and the means used to reach an ultimate choice, are extremely important to understanding consumer behavior. It has been shown that consumers use heuristic strategies to simplify complex choices, and help overcome cognitive shortcomings (Bettman 1979). Much research has been conducted to better understanding the effects of the consumer learning experience, memory, and the processing of available brand information (Biehal and Chakravarti 1986, Alba and

Hutchinson 1987, Hoch and Deighton 1989). Only through a better understanding of the phased decision making process, and the heuristics employed by consumers during this process, can one fully analyze the effects of varying contexts on brand choice.

In the past, traditional models of consumer choice were strongly dominated by linear compensatory models. Algebraic expressions were used to define a complex structure of weighing various attributes, and ultimately choosing a specific brand with no regard to the context of the choice. While a significant amount of research has been conducted to show empirical violations of such a model, some have been unsuccessful

(Johnson and Meyer 1994). This may be due to a proposed “washing away” of attraction and substitution effects (Johnson and Meyer 1994, Huber and Puto 1983). Ultimately the stream of literature examining context effects has proven such violations of a completely compensatory choice model and shown that the addition of an alternative to a given market may greatly affect consideration, as well as brand choice (Huber and Puto 1983,

3 See, for example, Bettman (1979), Huber and Puto (1983), Biehal and Chakravarti (1986), Alba and

Hutchinson (1987), Hauser and Wernerfelt (1990), Johnson and Meyer (1994)

10

Kardes, Herr and Marlino 1989). It has been shown that consumer choice involves sequential stages based on set goals and available information; in most cases a consumer relies on heuristics which include non-compensatory as well as compensatory screening.

A.

Phased Decision Making and Heuristics

Bettman (1979) discusses a phased strategy heuristic for evaluating a large number of alternatives which “the first phase is used to eliminate some alternatives from consideration and a second phase is used to make comparisons among those alternatives remaining”. The author also identifies that consumers may use such heuristics due to limited computational and processing skills.

Chaiken (1980) further studied heuristic information processing and concluded that low levels of involvement lead individuals to employ a heuristic strategy, which minimizes their cognitive effort. Heuristic information processing involves the use of general rules developed by individuals through their past experiences and observations.

Although heuristic information processing may be less reliable than a systematic strategy, individuals may choose to implement heuristics when economic concerns of cognitive effort outweigh concerns for reliability.

Biehal and Chakravarti (1986) recognize that consumers do not process all available brand and attribute information, and use the elimination heuristic is a result of consumers’ desires to minimize their information processing effort. After this noncompensatory screening stage, consumers then use a compensatory strategy to evaluate the remaining alternatives, and make a final choice. The authors conclude that brand information stored in memory greatly impacts consideration, and ultimately choice.

11

Further, difficulty in accessing memory information results in a lower probability of that memory brand being chosen.

Alba and Hutchinson (1987) further research on cognitive effort and heuristics through studying the effects of familiarity and consumer expertise on choice strategy.

Increased familiarity greatly reduces the cognitive effort expended in the consumer decision making process, and possibly increases the speed and accuracy of product related tasks. The authors also propose that product expertise effects cognitive structure, and the differentiation of various brands. Changes in cognitive structure affect the way decisions are framed by altering the size and composition of the set of alternatives the consumer is considering. This will become very important in understanding the effects of context on consideration and choice.

Hoch and Deighton (1989) explain the rationale behind consumer heuristics, specifically regarding product information. Many product markets offer little opportunity for learning from experience because of arrangements that constrain information availability. The authors also define motivation as the goals and intensity of consumer behavior. While highly motivated consumers are more likely to search for information and form hypotheses in the market, most consumer decisions are commonplace, and motivation tends to be relatively low.

Hauser and Wernerfelt (1990) further the study of heuristics as a result of imperfect information availability . The authors state “at any given consumption occasion consumers do not consider all of the brands available, but rather consider a much smaller set”. It is shown that the decision to consume is very different that the

12

decision to consider. Their research models the formation of consideration sets given the trade-offs between search costs and the benefits in choosing from a larger set of brands.

Kardes, Kalyanaram, Chandrashekaran, and Dornoff (1993), reinforce the idea of heuristics and a staged decision making process. Their study describes and tests the consumer logit model, and analyzes the cognitive process of consumer consideration and choice. A within-subjects logintudal experiment provided results conducive to a threestep approach to decision making (retrieval, consideration, and choice).

B.

Context Effects

Tversky (1977) discusses the use of relative similarity in decision making. The paper establishes that diagnostic factors of a particular product refer to the importance of classifications of its features; therefore these factors are highly sensitive to the set being considered. The author defines his diagnostic hypothesis as follows:

“When faced with a set of objects, people often sort them into clusters to reduce information load and facilitate further processing. Clusters are typically selected so as to maximize the similarity of objects within a cluster and the dissimilarity of objects from different clusters. Hence, the addition and/or deletion of objects can alter the clustering of the remaining objects. A change of clusters, in turn, is expected to increase the diagnostic value of features on which the new clusters are based, and therefore, the similarity of objects that share these features.”

Huber, Payne, and Puto (1982) analyzed the effect of an additional, dominated alternative to a consumer choice set. The authors define an asymmetric alternative as dominated by one alternative in the set, but not by at least one other. The results show that the addition of such asymmetric alternatives increases the share of the item that dominates it. The new alternative “helps” the items it is closest to, thus violating the similarity hypothesis. The substitution effect, which may seem intuitively correct, was

13

virtually negligible. Therefore, it may be suggested that a product line could increase sales by introducing a similar alternative that no one ever chooses.

Huber and Puto (1983) furthered the research on context by examining the effects of adding a new alternative which extended the boundaries of a consumer’s choice set.

Their experiments tested the degree to which the positioning of the new alternative differentially affects choice sets. The attraction effect is defined as a gravitational metaphor that we use to describe the empirical finding that a new item can increase the favorable perceptions of similar items in the choice set. The authors found that there is a substitution effect as well as an attraction effect which takes place, and that the attraction effect can be enhanced when the new alternative is a relatively weak substitute for the target brand.

Sujan and Bettman (1989) conducted a series of four studies to demonstrate the effects of differentiating a brand within a given product category. If a new alternative is strongly discrepant from the focal attribute of the product category will cause it to be subtyped, and is likely to be evaluated on its own features. However, if the new alternative is only moderately discrepant, it will result in a differentiated position within the original consideration set. The authors conclude that a brand with a subtyped position, compared with a differentiated position, is better associated with memory for the brand’s distinguishing attributes. The study implies that subtyping brands are important in explaining memory retrieval patterns and the formation of consideration sets.

Research on context effects is furthered by Kardes, Herr, and Marlino (1989). The authors studied the effects of a “decoy” brand, which serves as a reference point for

14

judging the target brand. It was hypothesized that assimilation in judgment (when the decoy is placed near the target) would lead to substitution in choice, and contrast in judgment (when the decoy is placed away from the target) would lead to attraction in choice. They found that in certain cases, the decoy was eliminated from the consideration set too quickly, and may not have served as a standard of comparison. The results showed that is situations where the decoy was placed closely to the target (assimilation), attraction effects were observed in judgment, while substitution effects were observed in choice.

Lehmann and Pan (1994) examined how new brand entries impact consideration sets. Two experiments show results concluding that becoming dominated after entry reduces consideration, while becoming dominating after entry does not increase consideration. The results also show that assimilation helps weak brands, but hurts strong brands.

Johnson and Meyer (1994) addressed the issue of attempting to model choice with a compensatory algebraic function, when in fact varying contexts may result in a

(partially) non-compensatory decision making process. A good description of choice behavior in one context may not come close to describing choice behavior in another context. The authors concluded that as a given consideration set increases in size, an individual is more likely to implement an elimination strategy thus decreasing the overall fit of a compensatory model.

Meyer and Johnson (1995) furthered their investigation of modeling consumer choice, and proposed three empirical generalizations of multiattribute choice systems.

First, attribute valuations are nonlinear, and dependent upon their given contexts. Next,

15

non-compensatory heuristics cause an “apparent over-weighting of negative attributes”

(elimination of options based on key attributes, regardless of their other attributes).

Lastly, the choice function recognizes proximity; that is the probability of choice is dependent upon its relative attractiveness to others in the set, as well as its similarity to those other options.

Dickson and Ginter (2000) discuss the implications of market segmentation and product differentiation. The authors define market segmentation as a state in which the total market demand can be broken up into segments, each with distinct demand functions. Product differentiation is defined as perceived differences from competitors based on any physical or nonphysical characteristic. Thus a competitor may achieve an advantage through a product differentiation strategy.

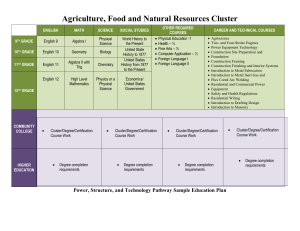

3. Methodology

I conducted a controlled experiment to test the effects of context on consumer choice in a monopolistically competitive environment. The study permitted the test of cluster size and cluster variance on consideration, as well as the effect of perceived distance to the cluster frontier on choice-given-consideration.

A.

Experiment

I chose to model monopolistic competition through the “market for dating” to engage the college students who participated in the experiment. This representative market contains all necessary components of a monopolistic competition. A pretest of college students determined the phrase “to date” is best defined as an implied but not explicit relationship. Photos of “college seniors”, who were about to enter the job market

16

were paired with starting salaries; these represented the various brands for a consumer to choose from based solely on two attributes: attractiveness and income. A pretest was conducted in which students evaluated the attractiveness of each of the photos on a scale from one to seven. Based on the results of that pretest, photos were selected to appear in the final controlled experiment .

Brands were selected to create two distinct clusters which consumers would be able to identify in the final experiment. The first, referred to as the income cluster had a significantly higher income, but lower attractiveness than the attractiveness cluster . Thus, the attractiveness cluster had significantly higher attractiveness, paired with lower income.

A control survey was formed with two brands in each cluster. The income cluster is comprised of two brands, Person A (highest income, lowest attractiveness) and Person

B (slightly lower income, slightly more attractive). The attractiveness cluster is also comprised of two brands Person Y (most attractive, least income) and Person X (slightly less attractive, slightly higher income).

Experimental manipulations to the control were used to alter cluster size, variance, and distance to the perceived cluster frontier. Each variation of the control examines the result of only one manipulation, holding all else constant. For example, a survey created to test the effect of increasing the size of the attractiveness cluster holds the variance of that cluster, and the distance to the perceived cluster frontier constant.

Six variations of each control survey (one male, one female) were developed. Two of the variations were developed to test the effects of cluster size, four were to test the effects of

17

cluster variation, and two of those synonymously tests the effects of distance to the cluster frontier.

1-

2-

3-

Survey

Control

Size Income

Size Attractiveness

4Variance/Frontier

7-

Income (Income)

5Variance/Frontier

Income

(Attractiveness)

6Variance

Attractiveness

(Income)

Variance

Attractiveness

(Attractiveness)

Purpose

Establish two distinct clusters

(Income and

Attractiveness)

Increase the size of the Income Cluster

Increase the size of the Attractiveness

Cluster

Increase the variance of the

Income Cluster

Increase the variance of the

Income Cluster

Increase the variance of the

Attractiveness

Cluster

Increase the variance of the

Attractiveness

Cluster

Manipulation

Income Cluster includes Person A and Person B. Attractiveness

Cluster includes Person X and

Person Y.

The addition of a “decoy” brand

(Person C) to the Income Cluster, holding variance and distance to cluster frontier constant.

The addition of a “decoy” brand

(Person Z) to the Attractiveness

Cluster, holding variance and distance to cluster frontier constant.

Increasing the income of Person A, moving the cluster frontier away from Person B.

Increasing the attractiveness of

Person B, moving the cluster frontier away from Person A.

Decreasing the income of Person Y.

Decreasing the attractiveness of

Person X.

The experiments were created online, and taken by college students. Each student took only one variation of the survey, and had no knowledge of any other variations. All of the brands to be considered were displayed simultaneously at the top of the survey page. To model the consideration stage of the consumer choice process, the subjects were first asked to evaluate each brand considering the statement: “I would like to date this person.” The results were measured on a scale ranging from one to seven (one meaning

“strongly disagree”, and seven meaning “strongly agree”). Lastly, the subject was asked

18

“If you had to choose only one of these people to date, which would you choose?” This modeled the choice or choice-given-consideration stage of the consumer choice process.

B.

Hypotheses

Following the Davies-Cline heuristics, I hypothesize that the probability of a consumer considering brands within a given cluster increases as the perceived size of the cluster increases. The addition of a third brand to either the income cluster or attractiveness cluster, should increase the proportion of students considering that given cluster. The probability of a consumer considering brands within a given cluster increases as the perceived variance of the cluster decreases. As cluster variance is increased either through manipulation of attractiveness or income, the proportion of students considering that cluster should decrease relative to the control. Lastly, the probability of a consumer choosing a brand, given consideration, increases as the perceived distance between the brand and the cluster frontier decreases. The increase in income of Person A, in the survey Variance/Frontier Income (Income), causing the cluster frontier to move farther away from Person B, should result in a decrease in the proportion of choice given consideration for Person B. Similarly, the increase in attractiveness in Person B, in the survey Variance/Frontier Income (Attractiveness), causing the cluster frontier to move away from Person A, should result in a decrease in the proportion of choice given consideration for Person A.

4. Results and Analysis

The results of the experiment attempt to empirically support the theoretical hypotheses pertaining to the marginal effects of Cluster Size and Cluster Variance on the

19

consideration stage of the consumer choice process, as well as the marginal effects of brand Distance from the Cluster Frontier on choice given consideration. For calculation purposes, evaluations of five and above signify consideration of a brand.

Pr(Consideration) has been calculated based on proportion of considerations to the number of observations.

A.

Cluster Size

When examining the effect of cluster size, it seems apparent that an increase in cluster size does in fact result in an increase in the probability of considering that cluster.

The difference in Pr(Consideration) of the income cluster increases from 12.0% to 15.6% with the addition of a third decoy brand, Person C. While the introduction of Person C does not seem to affect the probability of consideration for Person A, the increase in consumer confidence is shown in the drastic increase in probability of consideration in

Person B. Pr(Consideration) increases 3.6% with the increase in cluster size from the control.

The number of observations, n, is the number of possible considerations. A onesided 2-Proportion test conducted does not, however, show a p-value with significance at even the α=0.1 level. This is most likely due to the small sample size of the survey “Size

Income” which only had 48 respondents.

Income Cluster n

Pr(Consideration)

Difference from Control

Z

P-Value

Control

216

0.120

Size Income

96

0.156

0.036

-0.83

0.203

Similarly, increasing the size of the attractiveness cluster results in an increase in

Pr(Consideration) for that cluster. The probability of considering both Person X and

20

Person Y show an apparent increase after the introduction of the third decoy brand,

Person Z. Pr(Consideration) of the attractiveness cluster increases from 49.1% in the control survey to 57.8% in the “Size Attractiveness” survey.

A one-sided 2-proportion test between the values results in a Z-score of 1.71 and a p-value of 0.044. This shows a significant difference in the probability of considering the attractiveness cluster. n

Attractiveness Cluster Control

170

Pr(Consideration)

Difference from Control

0.491

Z

P-Value

Size Attractiveness

166

0.578

0.086

1.71

0.044

Combining the clusters we are able to see the overall effect of increasing cluster size on Pr(Consideration). The probability of consideration of brands in the market increases 11.8% with an increase in the size of both clusters. A two-proportion test of these results yield a Z-score of -3.13 and a p-value of 0.01.

Market n

Pr(Consideration)

Difference from Control

Z

P-Value

Control Increased Cluster Size

432 262

0.306 0.424

0.118

-3.13

0.01

The results regarding the effects of cluster size support the theoretical framework developed by Davies and Cline (2005). An increase in the number of brands within a cluster may be an indication to the consumer that a greater proportion of the true brand universe is observed, thus lessening the consumer’s external uncertainty (Davies and

Cline, 2005). The consumer may feel that an increased number of people in either the income or attractiveness cluster better represents the true population for dating.

21

Observing an increase in cluster size also decreases internal uncertainty concerning the cluster because it intuitively implies greater overall demand for that cluster and therefore helps in justifying their behavior (Davies and Cline, 2005). A larger income or attractiveness cluster may be helping people to justify their decision to consider that cluster, and possibly reduce their anticipation of regret.

B.

Cluster Variance

The analysis on the effects of cluster variance does not, however, support my hypothesis. The probability of considering a cluster should decrease as the variance of the cluster increases, due to an increase in internal and external uncertainties; this however is not supported by my findings. Only two of the four surveys, “Variance

Income (Income)” and “Variance Income (Attractiveness)”, showed a decrease in

Pr(Consideration) from the control. These decreases were very small, and both yielded insignificant p-values for a one-sided 2-proportion test.

Income Cluster n

Pr(Consideration)

Difference from Control

Z

P-Value

Control

216

0.120

Attractiveness Cluster Control n

Pr(Consideration)

Difference from Control

Z

P-Value

216

0.491

Variance Income

(Income)

64

0.109

-0.011

0.25

0.403

Variance Attractiveness

(Income)

184

0.533

0.042

-0.84

0.798

Variance Income

(Attractiveness)

202

0.089

-0.080

1.05

0.148

Variance Attractiveness

(Attractiveness)

228

0.500

0.009

-0.20

0.577

Combining the results of the four surveys we are able to see the effect of increased cluster variance on the entire market. Pr(Consideration) stayed about the same

22

between the control survey and the increased variance surveys, with a slight increase of about 4.4%.

Market n

Pr(Consideration)

Difference from Control

Z

P-Value

Control

432

0.306

Increased Variance

678

0.350

0.044

-1.53

0.937

These findings could be the result of many factors. The increases in variance created in each of the four surveys may not have been large enough to yield a response in our subject consumers. The results of the pretest in which the photos were evaluated on attractiveness, yielded results with a relatively small range. This placed significant limitations on the range of attractiveness included within a cluster. If the range of attractiveness within a cluster were to be any larger, the attractiveness of people would have overlapped between the clusters, thus blurring their distinction. For example, if the attractiveness of Person B were to be further increased (providing a larger cluster variance in the survey “Variance Income (Attractiveness)”), it would be very close, if not higher than, Person X. This would severely distort the idea of two separate and distinct clusters, confusing the consumer.

Similarly, the changes made to income had a larger effect on variance, but it may not have been large enough. A consumer who places more emphasis on attractiveness than income, may not have been affected by a change of $20,000. A larger manipulation may have supported the theoretical framework regarding the effects of cluster variance.

C.

Distance from Cluster Frontier

The effect of a brand’s distance from the cluster frontier, relative to the other brands within the cluster, is measured by evaluating choice-given-consideration. This is

23

the proportion of the number of times a brand was chosen in relation to the number of times the brand was considered, within a given survey. The number of observations, n, in this case is therefore the number of considerations made to that specific brand within the income cluster

4

.

The probability of choice-given-consideration seems to be in keeping with my hypothesis; the probability of a consumer choosing a brand, given consideration, increases as the perceived distance between the brand and the cluster frontier decreases, ceteris paribus . The increase in income for Person A, in the survey “Variance Income

(Income)”, moves Person B away from the cluster frontier while holding all else constant.

The probability of choice-given-consideration of the income cluster for Person B, however, stays constant. This is most likely due to the extremely small number of observations.

A one-sided 2-proportion test yielded a p-value of 0.5. Also, because the number of considerations in the income cluster is so small, the normal approximation may be inaccurate. A Fisher’s Exact Test, which accounts for this inaccuracy yielded an insignificant p-value of 1.00.

Person B n

Pr(Choice|Consideration)

Difference from Control

Z

P-Value

Fisher’s Exact Test: P-Value

Control Variance Income (Income)

21 3

0.667 0.667

0

0

0.5

1.00

4 We only evaluate the effects of cluster frontier to manipulations in the income cluster because these do not affect the brand to which the manipulation is made. For example, increasing the income of Person A keeps Person A at the same distance from the cluster frontier, while moving Person B away from it.

Contrary to the attractiveness cluster; decreasing the income of Person Y, moves Person Y away from the cluster frontier.

24

Similarly, the increase in attractiveness of Person B in survey “Variance Income:

Attractiveness” moves Person A away from the cluster frontier while holding all else constant. Pr(Choice|Consideration) falls from 40.0% in the control, to 0.0%. A one-sided two-proportion test yields a p-value of 0.034, however the Fisher’s Exact Test yields a pvalue of 0.464.

Person A n

Pr(Choice|Consideration)

Difference from Control

Z

P-Value

Fisher’s Exact Test: P-Value

Control Variance Income (Attractiveness)

5 3

0.4 0.000

-0.400

1.83

0.034

0.464

Combining the two instances, we are able to see the effect of distance to the cluster frontier on Pr(Choice|Consideration) on the entire cluster. The probability of choice-given-consideration falls from 61.5% in the control survey, to 33.3% in the

Variance Income surveys (for the instances of Person A and Person B positioned further from the cluster frontier). A two-proportion test of these results yield a Z-score of 0.095, which is significant at the α=0.1 level. However, it yeilds a Fisher’s Exact Test p-value of

0.365.

Income Cluster n

Pr(Choice|Consideration)

Difference from Control

Z

P-Value

Fisher’s Exact Test: P-Value

Control Variance Income

26 6

0.615 0.333

-0.282

1.31

0.095

0.365

While the decreases in Pr(Choice|Consideration) decreases in accordance with my hypothesis, the extremely small sample sizes (due to the low number of considerations) make it very difficult to claim statistical significance.

25

5. Economic Implications

The empirical results of this study support the framework suggested by Davies and Cline (2005), for firms competing in monopolistic competition. The positioning of brands within a brand universe suggests many strategies for monopolistically competitive firms to gain a short-term increase in sales over competitors.

For example, consider a monopolistically competitive market with four representative firms, divided equally into two distinct clusters, similar to the experiment.

A firm manufacturing Brand X has several options, according to the findings, for increasing overall demand for Brand X. The cluster which Brand X belongs to is comprised of only Brand X, and its competitor Brand Z. The brands are evaluated on only two attributes; price and quality. To increase the probability of choice for Brand X, the firm can increase Pr(Consideration) and/or Pr(Choice|Consideration).

To increase the probability of consideration of the cluster Brand X belongs to, the firm could introduce a decoy, Brand Y, to increase the size of the cluster. Introducing

Brand Y to the cluster as a decoy will draw market share away from the other cluster. An increase in Pr(Consideration) leads to an increase in the overall probability of choosing

Brand X, ceteris paribus .

Consider an example of milk producers, competing in a monopolistically competitive market for beverages. Pr(Choice|Consideration) for a milk producer may be high, while Pr(Consideration) may be low. This is perhaps the reason recent advertisements for milk do not promote one producer over another. The producers are

26

increasing Pr(Consideration) for the entire “milk cluster” by convincing the public of its large size.

Another approach is to move Brand X closer to the cluster frontier. According to these findings, this would increase the probability of choice-given-consideration for

Brand X. This could be accomplished in a number of ways. The introduction of a similar, Brand Y, to the cluster could potentially alter the cluster frontier. If Brand Y is symmetrically dominated, or dominated on all salient attributes, by the other brands in the cluster, the cluster frontier is not altered. However, if Brand Y is asymmetrically dominated, or dominated on only one attribute, the cluster frontier moves away from both

Brand X and Brand Z. In this case, if the decoy, Brand Y, is positioned correctly, it will move the frontier further from Brand Z than Brand X. While this would result in a reduction of choice-given-consideration for Brand X, the reduction for Brand Z would be greater. If the same firm owns Brand X and the decoy, then the firm wins at the expense of the competitor, Brand Z. Another path would be to overcome some technological constraint which currently exists. The firm producing Brand X could advertise, explaining that a technological constraint restricts the brands within the cluster.

Consider the example of a new brand of PC. If the market for computers is divided into two clusters, PC and Mac, the Pr(Consideration) for the new brand of PC is very high. However, due to the dominance of the existing brands (e.g. Dell, H.P.),

Pr(Choice|Consideration) is very low. In this case, there may be advertising aimed at showing consumers that the new brand is closer to the optimal cluster frontier than its competitors.

27

Any of these strategies would result in an increase of overall probability of choice for brand X. The results of this study provide a link between the consumer choice process and traditional beliefs surrounding monopolistic competition. While in the long-run, profits for firms competing in monopolistic competition are zero, it is believed that certain shocks to the market cause firms to have an increase in short-term profits. Such shocks commonly believed to exist are explained through the empirical results of this study, with an in depth look at product-market positioning.

6. Suggestions for Future Research

In the future, it would be beneficial to run a greater number of experiments testing the characteristics of cluster size, cluster variance, and perceived distance to the cluster frontier. While the results of this experiment provide evidence supporting the heuristic that the probability of consideration increases as cluster size increases, and the heuristic that the probability of choice-given-consideration decreases as a brand’s distance from the cluster frontier increases, the results do not support the heuristic that the probability of consideration decreases as cluster variance increases. This could be due to an increase in cluster variance that was not large enough to be detected by the students. Further differentiating the calculated variance from the control survey should yield results supporting the hypothesis regarding cluster variance.

A much larger sample would also be extremely advantageous. Because of the difficulties of administering seven different survey instruments, some of the manipulations had a lower number of observations than others. A larger number of observations for the survey “Size Income”, for example, may have yielded statistically

28

significant p-value. A larger sample size also may have statistically confirmed my findings on the effect of distance from the cluster frontier on probability of choice-givenconsideration.

7. Conclusion

The purpose of this analysis was to test the framework for choice in monopolistic competition as proposed by Davies and Cline (2005). Constructing a “brand universe” of potential dating partners with salient attributes of attractiveness and income, and collecting data from 578 college students, I found support for their heuristic that the probability of consideration increases as cluster size increases, support for their heuristic that the probability of choice-given-consideration decreases as a brand’s distance to the cluster frontier increases, but no support for their heuristic that the probability of consideration decreases as cluster variance increases.

Because of the imperfect and incomplete information of consumers in a monopolistic competition, they employ heuristics to help aide their decision making process. The consumer choice process is modeled here through three stages: productmarket perception, consideration, and choice. The results of this study provide evidence of consumer behavior in a monopolistically competitive setting. If used correctly, a firm in a monopolistic competition is able to gain short-run advantages over its competitors through manipulations to the market.

29

8. References

Alba, Joseph W., and J. Wesley Hutchinson. (1987). Dimensions of Consumer Expertise.

Journal of Consumer Research , 13, 411-454.

Bettman, James R. (1979). An Information Processing Theory of Consumer Choice.

Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Biehal, Gabriel and Dipankar Chakravarti. (1986). Consumers Use of Memory and

External Information in Choice: Macro and Micro Perspectives. Journal of

Consumer Research , 13, 382-405.

Chaiken, Shelly. (1980). Heuristic versus Systematic Information Processing and the Use of Source versus Message Cues in Persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology , 39 (November), 752-766.

Dickson, Peter R. and James L. Ginter. (1987). Market Segmentation, Product

Differentiation, and Marketing Strategy. Journal of Marketing , 51 (April), 1-10.

Davies, Antony, and Thomas Cline. (2005). A Consumer Behavior Approach to

Modeling Monopolistic Competition. Journal of Economic Psychology , 16(6),

797.

Hauser, John R., and Birger Wernerfelt. (1990). An Evaluation Cost Model of

Consideration Sets. Journal of Consumer Research , 16, 393-408.

Hoch, Stephan J., and John Deighton. (1989). Managing What Consumers Learn from

Experience. Journal of Marketing , 53(2), 1-20.

Huber, Joel, John W. Payne, and Christopher Puto. (1982). Adding Asymetrically

Dominated Alternatives: Violations of Regularity and the Similarity Hypothesis.

Journal of Consumer Research, 10 (June), 90-98.

Huber, Joel and Christopher Puto. (1983). Market Boundaries and Product Choice:

Illustrating Attraction and Substitution Effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 10

(June), 31-44.

Johnson, Eric J., Robert J. Meyer. (1984). Compensatory Choice Models and

Noncompensatory Processes: The Effect of Varying Context. Journal of

Consumer Research , 12, 169-177.

Kardes, Frank R., Paul Herr, and Deborah Marlino. (1989). Some New Light on

Substitution and Attraction Effects. Advances in Consumer Research, 16, 203-

208.

30

Kardes, Frank R., Gurumurthy Kalyanaram, Murali Chandrashekaran, and Ronald

Dornoff. (1993). Brand Retrieval, Consideration Set Composition, Consumer

Choice, and the Pioneering Advantage. Journal of Consumer Research , 20, 62-75.

Lehmann, Donald R. and Yigang Pan. (1994). Context Effects, New Brand Entry, and

Consideration Sets. Journal of Marketing Research , 31, 364-374.

Meyer, Robert and Eric J. Johnson. (1995). Emperical Generalizations in the Modeling of

Consumer Choice. Marketing Science , 14(3), 180-189.

Sujan, Mita and James R. Bettman. (1989). The Effects of Brand Positioning Strategies on Comsumers’ Brand and Category Perceptions: Some Insights from Schema

Research. Journal of Marketing Research , 26(4), 454.

Tversky, Amos. (1977). Features of Similarity. Psychological Review, 84(4), 327-352.

31

Appendix 1

Pretest Survey Instrument

Thank you for participating in this survey.

The purpose of the survey is to get your opinion.

Please answer each question truthfully. There are no right or wrong answers. Only your opinion matters.

DO NOT put your name on the paper. Your answers will remain completely anonymous.

In the following pages, you will see pictures of people. You will be asked to give your opinion of each person’s attractiveness.

Please give your honest opinion.

Do not go back and change your answers.

STOP. Do not turn the page.

32

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

33

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

34

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

35

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

36

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

37

Gender: Male Female

Would you consider dating any of these people? Yes No

Age: ______

38

Thank you for participating in this survey.

The purpose of the survey is to get your opinion.

Please answer each question truthfully. There are no right or wrong answers. Only your opinion matters.

DO NOT put your name on the paper. Your answers will remain completely anonymous.

In the following pages, you will see pictures of people. You will be asked to give your opinion of each person’s attractiveness.

Please give your honest opinion.

Do not go back and change your answers.

STOP. Do not turn the page.

39

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

40

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

41

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

42

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

43

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

1

Very

Unattractive

2 3

Unattractive Somewhat

Unattractive

4 5

Neutral Somewhat

Attractive

6

Attractive

7

Very

Attractive

44

Gender: Male Female

Would you consider dating any of these people? Yes No

Age: ______

Appendix 2

Survey Calculations

Control Male A Male B Male X Male Y

Attractiveness 1.938 2.656 3.719 5.047

Income

Distance to Cluster Frontier

Cluster Variance

85000

.371

.0079

75000

.133

45000

.357

.0156

35000

.286

45

Size (Income Cluster)

Attractiveness

Income

Distance to Cluster Frontier

Cluster Variance

Size (Attractiveness Cluster)

Attractiveness

Income

Distance to Cluster Frontier

Cluster Variance

Variance Income (Income)

Attractiveness

Income

Distance to Cluster Frontier

Cluster Variance

Variance Income (Attractiveness)

Attractiveness

Income

Distance to Cluster Frontier

Cluster Variance

Variance Attractiveness (Income)

Attractiveness

Income

Distance to Cluster Frontier

Cluster Variance

Variance Attractiveness

Attractiveness

Income

Distance to Cluster Frontier

Cluster Variance

Control

Male A

1.938

85000

.371

Male C

1.813

84000

.477

.0079

.0134

Male A

1.938

Male B

2.656

85000

.371

.0079

75000

.133

Male A

1.938

97000

.371

Male A

1.183

85000

.793

Male A

1.938

85000

.371

Male A

1.938

85000

.371

.0164

.0140

.0079

.0079

Female A

Male B

2.656

75000

.133

.133

Male X

3.719

45000

.357

Male B

2.656

75000

.293

Male B

3.250

75000

Male B

2.656

75000

.133

Male B

2.656

75000

.133

Female B

Male X

3.719

45000

.357

.0156

Male Z

4.094

43000

.233

.0115

Male X

3.719

45000

.357

Male X

3.719

45000

.357

Male X

3.719

45000

.357

Male X

3.469

45000

.455

.0156

.0156

.0832

.0173

Male Y

5.047

35000

.286

Male Y

5.047

35000

.286

Male Y

5.047

35000

.286

Male Y

5.047

35000

.286

Male Y

5.047

25000

.800

Male Y

5.047

35000

.286

Female X Female Y

46

Attractiveness

Income

Distance to Cluster Frontier

Cluster Variance

1.743

85000

.377

.0080

2.400

75000

.133

4.543

45000

.119

.0114

5.086

35000

.286

Size (Income Cluster)

Attractiveness

Income

Distance to Cluster Frontier

Female A Female C Female B Female X Female Y

1.743 1.686 2.400 4.543 5.086

85000

.377

73000

.588

75000

.133

45000

.119

35000

.286

Cluster Variance

Distance to Cluster Frontier

Cluster Variance

.0081

.300

.0104

.0114

.0134

Size (Attractiveness Cluster) Female A Female B Female X Female Z Female Y

Attractiveness 1.743 2.400 4.543 4.057 5.086

Income 43000 85000

.377

.0080

75000

.133

45000

.119

35000

.286

Variance Income (Income)

Attractiveness

Income

Distance to Cluster Frontier

Cluster Variance

Variance Income (Attractiveness)

Attractiveness

Income

Distance to Cluster Frontier

Cluster Variance

Female A Female B

1.743

97000

.377

2.400

75000

.293

.0164

Female A

1.686

85000

.746

Female B

.0134

2.943

75000

.133

Female X Female Y

4.543

45000

.119

5.086

35000

.286

.0114

Female X

4.543

45000

.119

Female Y

.0114

5.086

35000

.286

Variance Attractiveness (Income)

Attractiveness

Income

Distance to Cluster Frontier

Cluster Variance

Female A Female B

1.743

85000

.377

.0080

2.400

75000

.133

Female X Female Y

4.543

45000

.119

.0812

5.086

25000

.800

Variance Attractiveness

Attractiveness

Income

Distance to Cluster Frontier

Cluster Variance

Female A Female B

1.743

85000

.377

2.400

75000

.133

.0080

Female X Female Y

3.400

45000

.496

5.086

35000

.286

.0180

47

Appendix 3

Final Survey Instrument

Please indicate the extent to which you agree with the following statements.

Strongly

Disagree

Disagree

Somewhat

Disagree

Neutral

Somewhat

Agree

I would like to date person L.

I would like to date person M.

I would like to date person N.

I would like to date person P.

Agree

Strongly

Agree

If you had to choose only one of these people to date, which would you choose? (you must choose one)

Person L Person M Person N Person P

48

Prev Next

Please indicate the extent to which you agree with the following statements.

Strongly

Disagree

Disagree

Somewhat

Disagree

Neutral

Somewhat

Agree

I would like to date person L.

I would like to date person M.

I would like to date person N.

I would like to date person P.

Agree

Strongly

Agree

If you had to choose only one of these people to date, which would you choose? (you must choose one)

Person L Person M Person N Person P

49

Prev Next nFaQRUWxKT4U

50