Review of Australia`s Halon Essential use Requirements: Final

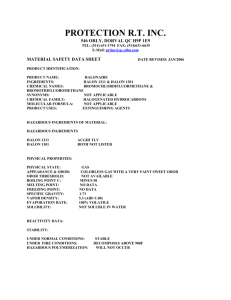

advertisement