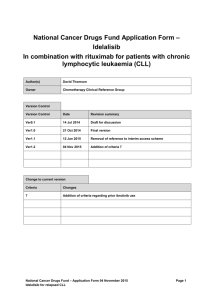

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

advertisement

LECTURE 4a CHRONIC LYMPHOCYTIC LEUKEMIA I. Background Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (chronic lymphoid leukemia, CLL) is a monoclonal disorder characterized by a progressive accumulation of functionally incompetent lymphocytes. It is the most common form of leukemia found in adults in Western countries. Peripheral smear from a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, small lymphocytic variety. Onset is insidious, and it is not unusual for CLL to be discovered incidentally after a blood cell count is performed for another reason. Enlarged lymph nodes are the most common presenting symptom, but patients may present with a wide range of symptoms and signs. Chemotherapy is not needed in CLL until patients become symptomatic or display evidence of rapid progression of disease. A variety of chemotherapy regimens are used in CLL. These may include nucleoside analogues, alkylating agents, and biologics, often in combination. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation is the only known curative therapy. II. Etiology As in the case of most malignancies, the exact cause of CLL is uncertain. The protooncogene bcl2 is known to be overexpressed, which leads to suppression of apoptosis (programmed cell death) in the affected lymphoid cells. CLL is an acquired disorder, and reports of truly familial cases are exceedingly rare. II. Epidemiology In US More than 17.000 new cases of CLL are reported every year. The true incidence in the US is unknown and is likely higher, as estimates of CLL incidence come from tumor registries, and many cases are not reported. Although the incidence of CLL in Western countries is similar to that of the United States, CLL is extremely rare in Asian countries (ie, China, Japan), where it is estimated to comprise only 10% of all leukemias. The incidence of CLL is higher among whites than blacks. The incidence of CLL is higher in males than in females, with a male-to-female ratio of 1.7:1. CLL is a disease that primarily affects the elderly, with the median age of presentation being 72 years. Median age is 58 years in familial cases. IV. Pathophysiology The cells of origin in most patients with CLL are clonal B cells arrested in the B-cell differentiation pathway, intermediate between pre-B cells and mature B cells. Morphologically, in the peripheral blood, these cells resemble mature lymphocytes. CLL B-lymphocytes typically show B-cell surface antigens, as demonstrated by CD19, CD20dim, CD21, and CD23 monoclonal antibodies. In addition, they express CD5, which is more typically found on T cells. CLL B-lymphocytes express extremely low levels of surface membrane immunoglobulin, most often immunoglobulin M (IgM) or IgM/IgD and IgD. Additionally, they also express extremely low levels of a single immunoglobulin light chain (kappa or lambda). An abnormal karyotype is observed in the majority of patients with CLL : deletion of 13q is the most common abnormality, which occurs in more than 50% of patients.. trisomy 12, which is observed in 15% of CLL patients, 17p13 deletions - deletion in the short arm of chromosome 17 is associated with loss of function of the tumor suppressor gene p53. deletions of bands 11q22-q23, observed in 19% of patients, Forty to 50% of patients demonstrate no chromosomal abnormalities on conventional cytogenetic studies. However, 80% of patients will have abnormalities detectable by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). The presence of cytogenetic abnormalities has prognostic value. Investigations have also identified a number of high-risk genetic features and markers, including the following: Germline immunoglobulin variable heavy chain (IgVH) IgVHV3-21 gene usage Increased CD38 expression Increased Zap70 expression Elevated serum beta-2-microglobulin levels Increased serum thymidine kinase activity Short lymphocyte doubling time (< 6 mo) Increased serum levels of soluble CD23 These features have been associated with rapid progression, short remission, resistance to treatment, and shortened overall survival in patients with CLL. V. History and Physical Examination Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (chronic lymphoid leukemia, CLL) present with a wide range of symptoms and signs. Onset is insidious, and it is not unusual for CLL to be discovered incidentally after a blood cell count is performed for another reason; 25-50% of patients will be asymptomatic at time of presentation. Enlarged lymph nodes are the most common presenting symptom, seen in 87% of patients symptomatic at time of diagnosis. A predisposition to repeated infections such as pneumonia, herpes simplex labialis, and herpes zoster may be noted. Early satiety and/or abdominal discomfort may be related to an enlarged spleen. Mucocutaneous bleeding and/or petechiae may be due to thrombocytopenia. Tiredness and fatigue may be present secondary to anemia; 10% of patients with CLL will present with an autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Richter syndrome or Richter transformation refers to the transformation of CLL into an aggressive large B-cell lymphoma and is seen in approximately 3-10% of cases. Patients will often present with symptoms of weight loss, fevers, night sweats, muscle wasting, (ie, B symptoms) and increasing hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. Treatment remains challenging and prognosis poor, with median survival in months. VI. Physical examination In addition to localized or generalized lymphadenopathy, patients may manifest the following: Splenomegaly (30-54% of cases) Hepatomegaly (10-20% of cases) Petechiae Pallor VII. Investigations Lab Studies: CBC count with differential shows absolute lymphocytosis with more than 5.000 lymphocytes/mmc. Some authors consider this to be a prerequisite for the diagnosis of CLL and classify cases that would otherwise meet the criteria as small lymphocytic lymphoma/diffuse well-differentiated lymphoma. Microscopic examination of the peripheral blood smear is indicated to confirm lymphocytosis. It usually shows the presence of smudge cells, which are artifacts due to damaged lymphocytes during the slide preparation. Peripheral blood flow cytometry is the most valuable test to confirm CLL. It confirms the presence of circulating clonal B-lymphocytes expressing CD5, CD19, CD20(dim), CD 23, and an absence of FMC-7 staining. Consider obtaining serum quantitative immunoglobulin levels in patients developing repeated infections because monthly intravenous immunoglobulin administration in patients with low levels of immunoglobulin G (<500 mg) may be beneficial in reducing the frequency of infectious episodes. The differential diagnosis of CLL includes several other entities, such as hairy cell leukemia, which is moderately positive for surface membrane immunoglobulins of multiple heavy-chain classes and typically negative for CD5 and CD21. Prolymphocytic leukemia has a typical phenotype that is positive for CD19, CD20, and surface membrane immunoglobulin and negative for CD5. Large granular lymphocytic leukemia has a natural killer cell phenotype (CD2, CD16, and CD56) or a T-cell immunotype (CD2, CD3, and CD8). The pattern of positivity for CD19, CD20, and the T-cell antigen CD5 is shared only by mantle cell lymphoma. Procedures: Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy with flow cytometry is not required in all cases but may be necessary in selected cases to establish the diagnosis and to assess other complicating features such as anemia and thrombocytopenia. For example, bone marrow examination may be necessary to distinguish between thrombocytopenia of peripheral destruction (in the spleen) and that due to marrow infiltration. Consider a lymph node biopsy if lymph node(s) begin to enlarge rapidly in a patient with known CLL to assess the possibility of transformation to a high-grade lymphoma. When such transformation is accompanied by fever, weight loss, and pain, it is termed Richter syndrome. Imaging Studies: Liver/spleen scan may demonstrate splenomegaly. Computed tomography of chest, abdomen, or pelvis generally is not required for staging purposes. However, be careful to not miss lesions such as obstructive uropathy or airway obstruction that are caused by lymph node compression on organs or internal structures. Chromosomal Testing Although not necessary for the diagnosis or staging of CLL, additional molecular testing now exists that may help predict prognosis or clinical course. At present, these tests are not recommended for routine use, although this may change with further research. VIII. Diagnostic Considerations Diagnostic criteria for CLL are : A peripheral blood lymphocyte count of greater than 5 G/L, with less than 55% of the cells being atypical; The cell should have the presence of Bcell-specific differentiation antigens (CD19, CD20, and CD24) and be CD5(+); A bone marrow aspirates showing greater than 30% lymphocytes. Differential Diagnoses has to be done with : Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Hairy Cell Leukemia Lymphoma, Diffuse Large Cell Lymphoma, Follicular Lymphoma, Lymphoblastic Lymphoma, Mantle Cell Lymphoma, Non-Hodgkin Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma T-Prolymphocytic leukemia (Former T-CLL) Mantle cell lymphoma can have a clinical presentation very similar to chronic lymphocytic leukemia (chronic lymphoid leukemia, CLL) but more aggressive. Several features aid in the distinction of mantle cell lymphoma from CLL. Mantle cell lymphoma expresses CD5 and CD19 but not CD23 antigen, which is expressed in CLL. Mantle cell lymphoma typically expresses FMC-7. Importantly, expression of CD20 is bright in mantle cell lymphoma, whereas it is dim in CLL. Anemia secondary to bone marrow involvement with CLL, splenic sequestration of red blood cells, and autoimmune hemolytic anemia associated with a positive Coombs test are included in the differential diagnosis of a patient with anemia who has CLL. Another problem to be considered is splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes. IX. Staging Two staging systems are in common use for CLL: the modified Rai staging in the United States and the Binet staging in Europe. Neither is completely satisfactory, and both have often been modified. These CLL staging systems have been unable to provide information regarding disease progression due to its heterogeneity. IX.1. Rai staging system The original 5-stage Rai staging system was revised in 1987 to a simpler 3-stage system. The revised Rai staging system divides patients into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups, as follows: Low risk (formerly stage 0) – Lymphocytosis in the blood and marrow only (25% of presenting population} Intermediate risk (formerly stages I and II) – Lymphocytosis with enlarged nodes in any site or splenomegaly or hepatomegaly (50% of presentation) High risk (formerly stages III and IV) – Lymphocytosis with disease-related anemia (hemoglobin < 11 g/dL) or thrombocytopenia (platelets < 100 x 109/L) (25% of all patients) Binet staging system The Binet stages are as follows: Stage A – Hemoglobin greater than or equal to 10 g/dL, platelets greater than or equal to 100 × 109/L, and fewer than 3 lymph node areas involved. Stage B – Hemoglobin and platelet levels as in stage A and 3 or more lymph node areas involved Stage C – Hemoglobin less than 10 g/dL or platelets less than 100 × 109/L, or both After successful treatment of immune cytopenias, CLL may be down-staged, X. Prognosis The prognosis of patients with CLL varies widely at diagnosis. Some patients die rapidly, within 2-3 years of diagnosis, because of complications from CLL. Most patients live 5-10 years, with an initial course that is relatively benign but followed by a terminal, progressive, and resistant phase lasting 1-2 years. During the later phase, morbidity is considerable, both from the disease and from complications of therapy. Prognosis depends on the disease stage at diagnosis as well as the presence or absence of high-risk markers. The classic poor prognostic factors are : • Advanced Rai or Binet stage • Peripheral lymphocyte doubling time <12 months • Diffuse marrow histology • Increased number of prolymphocytes or cleaved cells • Poor response to chemotherapy • High 2- microglobulin level • Abnormal karyotyping The new poor prognostic factors (which are not widely used and accepted and need developed laboratories) are : Immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region mutational status; CD38 status ZAP70 status XI. Clinical course Although CLL is predominantly an indolent disorder of late middle-aged or elderly individuals, the disease may cause significant morbidity. In its least aggressive pattern, patients die of causes unrelated to CLL at a rate that closely follows actual norms for their age. In its most aggressive form, patients may die within 1 to 2 years after diagnosis. At presentation, patients are often asymptomatic. Initial symptoms are generally secondary to lymphocytosis or anemia. As the disease advances, the following may appear: increasingly elevated lymphocyte counts; progressive lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly; and more severe anemia, granulocytopenia, or thrombocytopenia. Late in the course of the disease, hypogammaglobulinemia and progressive splenomegaly are prevalent. Infections are common with disease progression and are the leading cause of death in patients with CLL. Most CLL patients die of infection or illness unrelated to the leukemia. Long-term consequences of CLL include the development of autoimmune phenomena and/or transformation. Autoimmune Manifestations - The development of autoantibodies is a cardinal feature of the natural history of CLL. In general, autoantibodies are generated against formed elements of the hematopoietic system. Autoimmune manifestations in CLL are myriad, as follows: AIHA - Autoimmune hemolytic anemia develops in between 10% and 15% of patients with CLL. Usually, these patients are Coombs’ positive, and clinical hemolysis is evident. Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) - is less common, occurring in 2% to 5% of patients with CLL. Pure red cell aplasia - pure red cell aplasia occurs less often. Patients with this autoimmune manifestation are often Coombs’ negative, despite clinical hemolysis. Examination of the bone marrow reveals a deficiency of red blood cell precursors. Autoimmune neutropenia Cold agglutinin disease Paraneoplastic pemphigus Neuropathies Evans syndrome XII. Treatment Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (chronic lymphoid leukemia, CLL) do not need to be treated with chemotherapy until they become symptomatic or display evidence of rapid progression of disease, as characterized by the following: Weight loss of more than 10% over 6 months Extreme fatigue Fever related to leukemia for longer than 2 weeks Night sweats for longer than 1 month Progressive marrow failure (anemia or thrombocytopenia) Autoimmune anemia or thrombocytopenia not responding to glucocorticoids Progressive or symptomatic splenomegaly Massive or symptomatic lymphadenopathy Progressive lymphocytosis, as defined by an increase of > 50% in 2 months or a doubling time of less than 6 months Response assessment Complete response : All lymph nodes smaller than 1 cm; normal liver and spleen; no constitutional symptoms; leukocyte counts > 1500/mm3; normal circulating B lymphocytes; platelet levels > 100,000/mm3; hemoglobin level > 11 g/dL; normocellular bone marrow with < 30% lymphocytes; no B-lymphoid nodules Partial response : Decrease in lymph nodes by 50% or more; liver and spleen sizes decreased by 50% or more; any constitutional symptoms; leukocyte counts > 1500/mm3 or > 50% improvement; circulating B lymphocytes decreased by 50% or more; platelet levels > 100,000/mm3 or > 50% increase from baseline; hemoglobin level > 2 g/dL from baseline; hypocellular bone marrow or > 30% lymphocytes or B-lymphoid nodules Treatment recommendations for symptomatic CLL Low risk (formerly Rai stage 0): Patients with no indications should be observed - require only periodic follow-up. In multiple studies and a meta-analysis, early initiation of chemotherapy has failed to show benefit in CLL. Intermediate risk (formerly Rai stages I and II): Patients with no indications should be observed High risk (formerly Rai stages III and IV): The overall survival rates for all of the recommended treatments are similar; therapies should be chosen based on the individual patient characteristics and a review of toxicities Fludarabine-based therapy is preferred for patients with CLL A variety of chemotherapy regimens are used in CLL. These may include nucleoside analogues, alkylating agents, and biologics, often in combination. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation is the only known curative therapy. The complete response (CR) is defined by absence of lymphocytosis, lymphadenopathy, and organomegaly without significant cytopenias. • • Monotherapy – glucocorticoids – alkylating agents (Chlorambucil, Cyclophosphamide) – purine analogues (Fludarabine, Cladribine, Pentostatin) Combination chemotherapy – Chlorambucil/ Cyclophosphamide + Prednisone – Fludarabine + Cyclophosphamide +/- Mitoxantrone • • • • • • • – CVP, CHOP Monoclonal antibodies (monotherapy and in combination) – Alemtuzumab (anti-CD52) – Rituximab (anti-CD20) Splenectomy Radiotherapy Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation – allogeneic with reduced intesity conditioning – autologous New and novel agents – Oblimersen – bcl2-directed antisense oligonucleotide – Lenalidomide – Flavopiridol – Anti-CD23 – Anti-CD40 Vaccine strategies Supportive therapy (allopurinol, G-CSF, blood and platelet transfusion, immunoglobulins, antibiotics) Treatment strategy : Treatment of complications : Up to 25% of patients with CLL demonstrate autoimmune anemia, thrombocytopenia, or both. Simultaneously, immune incompetence is present, characterized by a progressive profound hypogammaglobulinemia, predisposing patients to a number of infections, the most common being bacterial pneumonias. Patients experiencing frequent bacterial infections associated with hypogammaglobulinemia are likely to benefit from monthly infusions of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). Studies of prophylactic IVIG in patients with CLL have not demonstrated a survival benefit, but have shown a significant decrease in the occurrence of major infections and a significant reduction in clinically documented infections. Prednisone alone, usually in a dose of 20-60 mg daily initially, with subsequent gradual dose reduction, may be useful in patients with AIHA. Rituximab, alone or as part of a combination regimen, can be very effective in eliminating the B-cell clone that induces autoimmune disorders, particularly for patients with autoimmune thrombocytopenia. IVIG can be used as a short-term measure in patients who have severe thrombocytopenias or pending surgery. Thrombopoietin receptor agonists have been used with some success as in primary ITP. Extremely high white blood cell counts (>300,000/µL) may produce a hyperviscosity syndrome with altered central nervous system function and/or respiratory insufficiency. Leukocytapheresis and urgent therapy with prednisone and chemotherapy may be required. Virtually all patients requiring therapy should also be given allopurinol to prevent uric acid nephropathy. Splenectomy Refractory splenomegaly and pancytopenia is a common problem in patients with advanced CLL. Occasionally, these patients require splenectomy. Substantial improvements in hemoglobin and platelet counts are observed in up to 90% of patients undergoing splenectomy. All patients with CLL who are to undergo splenectomy should be immunized at least 1 week in advance against the pneumococcus, Haemophilus influenza, and Neisseria meningitidis.