July 2014 - Building Bright Futures

advertisement

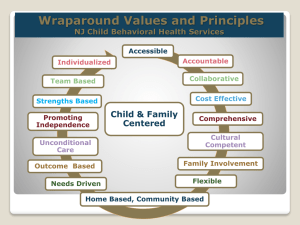

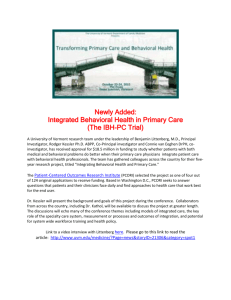

Policy Brief Behavioral Health Integration in Pediatric Primary Care Settings Traci Sawyers, July-August 2014 THE PROBLEM One in five children experience mental health problems and up to one-half of all lifetime cases of mental illness begin by age 14.1 Yet, it’s estimated that 70 percent of children and adolescents who need treatment do not receive mental health services.2 With concerning rates of adolescent depression and drug use – not to mention the tragic trend in school shootings - the behavioral health of children and youth is an urgent public health issue. 3 The prevalence and early onset of mental health issues combined with research on brain development and early risk and protective factors, as well as the increased availability of screening and assessment tools and evidence-based practices all support the rationale for integrating behavioral health services in pediatric primary care settings for children and youth. 4 BACKGROUND The National Institute for Health Care Management defines children’s mental health as “successful performance of mental functioning resulting in productive activities, fulfilling relationships with other people, and the ability to adapt and to change and to cope with adversity; mental health is indispensable to personal well-being, family and interpersonal relationships, and contribution to the community or society.”5 The terms mental and behavioral health are often used interchangeably. However behavioral health includes substance abuse addiction, mental illness and emotional well-being, and encompasses promotion, prevention, early intervention and treatment. Pediatric primary care, which includes pediatricians and family medicine providers, has unparalleled access to children: nationally, 94.5 percent of children birth to five-years old are estimated to have health insurance, and 89.7 percent report having a preventative well child visit in the last 12 months.6 Therefore, pediatric primary care providers have a unique opportunity to prevent and address behavioral health in the medical home. Pediatric primary care providers typically have longstanding and trusted relationships with families and can routinely screen for emerging problems in child or family functioning, promote healthy lifestyles, build resilience and protective factors and mitigate toxic stress.7 Despite this potential to address behavioral health challenges early, there are two main roadblocks: pediatric primary care clinicians are not fully trained to diagnose or treat behavioral health problems, and, referrals to community-based mental health providers can be a challenge. National studies show that over half of primary care doctors are not successful in referring patients to mental health services for a variety of reasons including stigma, insurance and payment barriers, or a shortage of mental health providers that result in long waitlists. As a result, depression and other behavioral health problems can go undiagnosed or are not treated adequately. 8 In response, Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children and Adolescents, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and others have recommended that pediatricians address pediatric behavioral health problems - such as depression, anxiety and substance abuse - by routinely screening, providing anticipatory guidance and referring for additional treatment when necessary.9 In this way, they can reach a large number of children who otherwise would not seek out behavioral health care until problems worsened. the pediatric practice hires embedded behavioral health staff.12 Many children in the U.S. have behavioral health symptoms that do not rise to the level of a formal disorder diagnosis but are still significant. This number is estimated to be twice the prevalence of children with severe emotional disorders.10 Getting support from the pediatric provider can again be the difference between prevention/mitigation or waiting for much more costly interventions if problems escalate. INTEGRATION – Primary care practice has behavioral health clinicians on staff. Research, especially over the last 10 years, has proven that prevention and early intervention can lessen risks and build protective factors which impact health outcomes, school readiness and health costs.11 Protective factors include a stable and loving family, economic security, and connections with healthy schools and communities. Risk factors include traumatic events, maternal depression, parental substance abuse and poverty. These are all important parts of pediatric health supervision and the medical home. While AAP and others have called for more behavioral health training for pediatric providers, coordination and co-location with behavioral health specialists or hiring behavioral health staff in the pediatric practice can help significantly with diagnosing and treating behavioral health issues. Collaboration between primary care and behavioral health specialists generally fall in to three areas: 1) consultation with a behavioral health expert and referral, if necessary; 2) co-location of behavioral health staff in a pediatric practice; or 3) full integration of behavioral health and primary care services where CONSULTATION – Behavioral health experts are available by telephone or video conference to provide consultation and help with referral. CO-LOCATION – Primary care and behavioral health clinicians are physically located in the same treatment setting. Behavioral health specialists include psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, clinical social workers, licensed professional substance abuse counselors, nurses with advanced psychiatric training, family therapists, neurologists, early intervention specialists, developmental-behavioral pediatricians and adolescent medicine specialists.13 The federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration reports that the United States has only one-fourth of the child psychiatrists it needs.14 Waiting lists for these services can be very long. Therefore, in Vermont and nationally, child psychiatry consultation models have become more prominent, assisted by the increasing use of telemedicine. In these models, primary care and other providers are able to access a psychiatrist who provides consultation when issues emerge. In some cases, psychiatric services are delivered directly via telemedicine from a remote site. Another promising integration approach is care coordination. Care coordination is defined as a patientand family-centered, assessment-driven, team-based approach designed to meet the needs of children and youth while enhancing the care giving capabilities of families.15 Care coordination is typically delivered by nurses or clinical social workers and can be centralized or embedded in a practice. It addresses interrelated medical, social, developmental, behavioral, educational and financial needs to achieve optimal health and wellness outcomes. Care coordination has been found to decrease unnecessary primary care or emergency department visits and hospitalizations, as well as improving family satisfaction.16 An AAP policy statement on this topic, “Patient and Family Centered Care Coordination: A Framework for Integrating Care for Children and Youth across Multiple Systems,” was published in Pediatrics on May 1, 2014. Whatever approach, integrated care is the seamless provision of health care services from the perspective of families – and involves them throughout the process. It also makes a fundamental shift from treatment of disorders to prevention, with the focus on identifying early onset of behavioral health concerns and mitigating the consequences. WHAT IS BEING DONE There are several behavioral health integration projects being piloted in pediatric primary care settings throughout Vermont. These largely fall into four categories.17 1) Psychiatric consultation which often includes technical assistance and training for primary care providers. In this model, psychiatry is offered via contract or other mechanisms with a university or private practice either on site, by phone, by telemedicine, by email, or as part of grand rounds. Consultation is used by medical practices, Designated Agencies (i.e. Vermont’s Community Mental Health Centers) and Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC’s). Providers include Otter Creek Associates, the University of Vermont’s Department of Psychiatry’s Vermont Center for Children, Youth and Families (VCCYF), the Brattleboro Retreat, and Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center’s Department of Psychiatry. 2) A licensed, Ph.D. psychologist on-site within a pediatric primary care practice. Co-located psychologists are integrated in practice sites and provide treatment, behavioral health consultation, triage and referral assistance and other support to the primary care physicians and staff. 3) Case management which involves a medical social worker co-located in a pediatric primary care practice. A medical social worker provides case management for Medicaid eligible children, especially those with demonstrated behavioral health needs. This is a Department of Mental Health contract with the area Designated Agency. 4) Care coordination within pediatric primary care. The Vermont Blueprint for Health’s Community Care Teams, located in each region of Vermont, work with primary care providers to assess patients’ needs, coordinate community-based support services, and provide multidisciplinary care for the general population including adults. Care coordination is part of this work. Those on Community Care Teams include nurses, a health educator, a community resource social worker, a behavioral health social worker, and a certified dietician. These teams are formed on a population basis and can be accessed by primary care providers in the region. In Chittenden County, Hagan, Rinehart and Connolly Pediatrics, joined with University Pediatrics and Timberlane Pediatrics to form a Community Health Team specifically focused on pediatric primary care. These practices receive embedded care coordination staff via the Blueprint and focus on child and family needs using Bright Futures guidelines, care coordination and collaborative community teaming. The Vermont Children’s Health Improvement Project (VCHIP) has also created a statewide Pediatric Care Coordination Learning Collaborative further supporting this care coordination work, using evidence-based tools and findings. This group of primary care providers will develop learning objectives and materials based on Boston Children’s Hospital’s “Pediatric Care Coordination Curriculum” published in 2014. The learning collaborative has regular in-person learning sessions or conference calls through January 2015. This work also includes understanding the landscape of health care reform, collaborating with Vermont’s Title V Maternal and Child Health Program and understanding and using Medicaid care coordination codes and advocating for payment of these services by all payers. 1) Support the expansion of behavioral health integration initiatives and strategies as described above – including consultation, colocation with behavioral health specialists or integration by hiring embedded behavioral health specialists in the pediatric primary care practice. Instead of having children on long waiting lists to see psychiatrists or other specialists, it makes sense to have pediatric providers access support and consultation when needed. This continues to build the capacity and skill of the practice in this critical area. Across the state there are other care coordination initiatives that have been formed at the community level and are often supported financially through feefor-service models and grants. For example, as part of project LAUNCH, two practices – the Community Health Center of Burlington and University Pediatrics - are piloting a care coordination model using clinical social workers and with a focus on Chittenden County’s growing New American population. 2) Use and develop health information technology to support integrated care. This includes electronic health records, and also using technology to improve systems and provide care (e.g., telehealth). Beyond these four general areas and its outpatient clinic, VCCYF also provides several related supports including a Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Residency Training program, a Child Psychology Internship program, Family Wellness Coach Training and much more. VCCYF, VCHIP and Vermont’s Integrated Family Services Division have also created a Center for Training in Evidence Based Approaches to Family Treatments with the goal of reducing childhood emotional and behavioral disorders. Trainings are offered to mental health clinicians located in pediatric primary care, Designated Agencies and FQHC’s. RECOMMENDATIONS There are many important steps that Vermont should take to support pediatric primary care providers in promoting the behavioral health and well-being of the children they care for. 3) Understand the landscape of quality metrics (e.g., National Committee for Quality Assurance) and health care reform. Moving from procedure and episodic-based payment, to payment based on health outcomes makes this type of integration key. Understand that children are not the drivers of current health care costs but their healthy development is key to containing long-term costs. 4) Support increased behavioral health competencies of pediatric primary care staff. The American Academy of Pediatrics has proposed competencies for providing behavioral services in pediatric primary care settings and recommends steps toward achieving them. However, AAP does not consider this a current expectation. It will require innovations in residency training and continuing medical education, as well as systems changes in the ways behavioral health is financed before enhancements in clinical practice can happen. 5) Increase reimbursement to cover screening and preventive services so they are provided in primary care. The evidence is there that proves this makes a difference and saves money down the line. 6) In addition to screening and assessment of children’s social and emotional health and development, ensure that validated, reliable screening tools are also available and used for maternal depression, family violence, substance abuse and other family issues that affect children. 7) Sources: 1 Marshall, N., Integrating Behavioral Health and Primary Care for Children and Youth, SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions, 2013. 2 Ibid. 3 Ginsburg, S., and Foster, S., Strategies to Support the Integration of Mental Health into Pediatric Primary Care, National Institute for Health Care Management, 2009. 4 Ibid. Improve or establish effective coding and billing systems for integrated services. Practices must be able to use Medicaid codes routinely and private insurers must pay for care coordination and other integration approaches. 5 Ibid. 6 National Survey for Children’s Health, 2011-12 7 American Academy of Pediatrics, The Future of Pediatrics: Mental Health Competencies for Pediatric Primary Care, Pediatrics, 2009. 8) Address barriers to referral, communication and information sharing between primary care and behavioral health staff. Even a regular exchange of information is currently a challenge. 8 Ibid. 9 Ibid. 10 Ibid. 9) Encourage a family based approach to pediatric care such as the model VCCYF uses. It considers risk, protective factors and the emotional health of the entire family when deciding on treatments. This is important because the child is influenced by genetic factors, environmental factors and their interaction. As health care reform continues in our county and specifically in Vermont, one of the most fundamental pieces of that work should be the integration of behavioral health in primary care. Gains are clearly seen in the pediatric setting. Vermont must do all it can to continue the important work it has started in this area so all children and families have access to this comprehensive, family centered care. 11 Ginsburg and Foster. 12 Ibid. 13 AAP - The Future of Pediatrics: Mental Health Competencies for Pediatric Primary Care, 14 http://www.aboutourkids.org/articles/may_mental_h ealth_month_factoftheday 15 American Academy of Pediatrics, Patient-and FamilyCentered Care Coordination: A Framework for Integrating Care for Children and Youth Across Multiple Systems, Pediatrics, 2014. 16 17 Ibid. The Vermont Children’s Health Improvement Project About These Policy Briefs: This is one in a series of policy briefs designed to focus our collective attention on issues that affect our young children and families. These briefs, as well as an annual How Are Vermont’s Young Children? report are part of an initiative by Building Bright Futures State Advisory Council, connected to the Vermont Early Childhood Framework recently unveiled at Governor Shumlin’s Early Childhood Summit in 2013. For more information, call Building Bright Futures at 802-876-5010 or find out more on line: www.buildingbrightfutures.org) About Project LAUNCH: Project LAUNCH (Linking Actions for Unmet Needs in Children’s Heath) is a federal initiative funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The Vermont Department of Health (VDH) received a five-year SAMHSA Project LAUNCH grant in 2012. Project LAUNCH is being piloted in Chittenden County and is grounded in a comprehensive view of health that addresses the physical, emotional, social, cognitive and behavioral aspects of well-being. Building Bright Futures State Advisory Council, Inc. serves as the grantee of VDH for Project LAUNCH implementation. About the Author: Traci Sawyers holds a M.A. in public policy from Tufts University and has 25 years experience in child and family policy, maternal/child health and behavioral health. In these areas, she has been a writer, lobbyist, researcher, planner, program administrator, consultant, facilitator, grant writer/administrator, elected official, and organizational director. She is currently the Early Childhood Health Policy Expert for Building Bright Futures and Vermont’s Project LAUNCH initiative.