May 18 2014 Michigan State Conference on Food Justice I want to

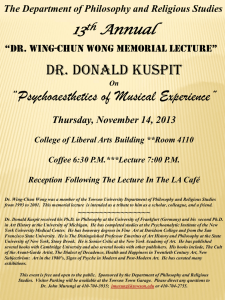

advertisement

May 18 2014 Michigan State Conference on Food Justice I want to begin by reading a passage from J.M. Coetzee’s The Lives of Animals: “It’s that I no longer know where I am. I seem to move around perfectly easily among people, to have perfectly normal relations among them. Is it possible, I ask myself, that all of them are participants in a crime of stupefying proportions? Am I fantasizing it all? I must be mad! Yet every day I see the evidence. The very people I suspect produce the evidence, exhibit it, offer it to me. Corpses. Fragments of corpses that they have bought for money. It is as if I were to visit friends, and to make some polite remark about the lamp in their living room, and they were to say, ‘Yes, it’s very nice, isn’t it? Polish-Jewish skin it’s made of, we find that it’s best, the skins of young Polish-Jewish virgins.’ And then I go to the bathroom and the soap wrapper says, ’Treblinka – 100% human Stearate’. Am I dreaming, I say to myself? What kind of house is this? Yet I am not dreaming, I look into your eyes, into Norma’s and the children’s and I see only kindness, human-kindness. Calm down, I tell myself. You are making a mountain out of a molehill. This is life. Everyone else comes to terms with it. Why can’t you? WHY CAN’T YOU?” (p. 70ff) There are multiple ways to read this haunting book. The essays in Philosophy and Animal Life provide some beginning interpretations. I want to use the most straightforward understanding. I want to use it simply as displaying, touchingly, poignantly, a character, Elizabeth Costello, overwhelmed by the horror of what we do to animals. It’s that reading that I want to stand as background for us as I pose the question that Jeff, Garry and I take on here. And that question, quite simply, is this: What allows us finally to act in accord with beliefs that although strongly held, ask a great deal of us in terms of dramatic life changes? Specifically, in terms of what we want to address this week-end, what keeps us from making moral choices in relation to what we eat? What helps us make those moral choices? The answer to that kind of question, we all know, is enormously complex - if it is answerable at all. Certainly I don’t have an answer. But I do know, as we all do, that work like Coetzee’s seems to have an important role to play in going from thinking we ought to act – to actually acting. If the ground has been prepared in us, whatever that means, then the character Elizabeth Costello, for instance, speaks to us. And often enough, we answer. We stop participating in systems we know to be inhumane. And her voice, Coetzee’s words, bear some of the responsibility for our changed ways of living. 1 The essayist Jonathan Savran Foer’s book Eating Animals can have a similar effect as he speaks intimately about his grandmother, her experiences, and his own decisions. But how about Philosophy? How should that academic discipline put its shoulder to this wheel? We don’t tell stories that touch the heart. At least that has not been the discipline’s métier in the past. So is there a role for Philosophy here? Can its particular methods be useful in helping us go beyond abstract knowledge to humane action? Can Philosophy be a force in helping us stand differently to the animals we now allow to be factory farmed and used for food? That is the puzzle the three of us have come to in different ways. It defines the project we take on here. Our answer? Probably not, done in ways that Philosophy has traditionally been done. But likely yes, if we fashion an alternative way of understanding the work of philosophy. And it is that alternative we want to talk about today. So let me start: I get the easy part: I want to just give you all a brief introduction to our project. Garry and Jeff will then do the hard work of showing what our suggestion actually looks like. So in the next few minutes, I want to do 3 things: 1) Very briefly sketch an understanding of how philosophy typically has been seen to work; 2) Show some of the problems with that template; and 3) point in the direction of a different understanding of how to do Philosophy, a way that opens up important conceptual space between academic philosophy traditionally understood in this way, and poetry or narrative like Coetzee’s. I will want to point to this middle ground, this alternative. Done in this alternative way, we believe, philosophy can touch us, can move us to action, in ways not dissimilar to the work of novelists like Coetzee or essayists like Foer. First, then: A Standard way of doing ethics: Let me start by briefly laying out what I hope is not a caricature, but rather a fairly straightforward picture of the underlying logic typically used in presenting a philosophical response to a moral question. At minimum, I can say quite honestly, it has been the picture I have assumed when teaching, speaking publicly or even talking seriously to friends. (And yes, complaints have been registered on that score.) On this typical view, what philosophy, and especially ethics, does is to invite students or others into a space occupied by the Philosophy cannon, asking them to leave behind many of their own ethical insights. Why? Because the way non-philosophers think about – and end up living – their/our own moral lives is thought to be too haphazard. People in general are ostensibly too bound to specific and inadequately justified responses. We/academic Philosophy can offer help. 2 What a philosophical response supposedly does, then, on this view, is to show how Philosophy can display the power of universal principles, hopefully embedded in larger theories. It is these theoretical approaches that will ultimately better guide all of our moral lives. And, importantly, we accept these principles, and the theories from which they are derived, on the basis of well thought out argument. This careful and rigorous construction and justification of theory is ostensibly what Philosophy has been all about, and should continue to be about, according to this view. And especially when we teach, what our classes now should be all about is teaching our students first of all about rigor and argument and the importance of using those to test claims. Second, we should give them the cannon’s theories. We then send them back to their world, ostensibly better equipped to understand and lead more moral lives. I don’t think I am being unfair in saying this is the picture that, for instance, Russ Shafer-Landau assumes in his introductory text The Fundamentals of Ethics. (p. 14: The Role of Moral Theory: “Knowing what to do…requires that we have a sure grasp of very general moral principles.” “Moral Philosophy is primarily a matter of thinking about the attractions of various ethical theories.” And page 8: “…our moral thinking should have two complementary goals – getting it right, and being able to back up our views with flawless reasoning.” So in classes in which we talk about food justice or how we do and ought to stand to animals, we might use arguments like Peter Singer’s, for instance, and utilitarian theory in general, to help students reflect on factory farming as well as other moral challenges in our system of food production and dissemination. Hopefully this brief sketch captures, without being too much of a caricature, much of what Philosophy takes itself to be doing. Ultimately, this is the underlying logic: our everyday moral lives are lived too haphazardly, too bound to specific and inadequately justified responses. What theory and principle, justified thru rigorous argument, have to offer is a better guide to people’s own moral lives. What we are uncomfortable about: So what is wrong with that picture? We want to claim that whatever Philosophy’s strengths, (and remember, we are not arguing against all of Philosophy in all of its projects) what this way of doing Philosophy does not do is help us act in accord with difficult beliefs, ones that although strongly held, ask a great deal of us in terms of dramatic life changes. It does not, as Coetzee and Foer do, help us stand differently to the animals we now allow to be factory farmed and used for food. And remember, too, that we are making no strong causal claims here. Why we come to see anything; why we come to act on what we see: we do not have the skills, if anyone does, carefully to address those causal questions. But we are comfortable making a far weaker claim: stuff we read seems to matter in making these hard choices, often in taking the difficult step of going from belief to action. 3 And it seems to us that Phil as it is traditionally done, disqualifies itself as a candidate for providing that kind of help. Why do we believe that? In short, because the defining structure of doing Philosophy as it has traditionally evolved, ends up functioning to keep us comfortably at a distance from our most challenging issues. It does not help us confront them. Now there is a great deal of work to be done in order to support this claim. Why, for instance, do we believe that universals are distancing? What exactly do we find wanting in theory? And in fact, what sense of ‘theory’ are we using here? Further, why does solely relying on argument fail when our project is to help make the often painful transition from commitment to action? Jeff’s and Garry’s discussions here will begin to point to at least some of the work needed to supply answers to these questions. But the truth is that the detailed support lies largely beyond what we can sketch here. But let me offer at least what is a helpful beginning description of the limits of Philosophy as it has come to be done. This description comes from the work of Cora Diamond. Because I think Jeff is going to say a little more about her, let me just point in the general direction she takes. She organizes her concern about Philosophy’s capacity to help us see and then act, around the concept of deflection. Essentially, she claims that the way Philosophy has traditionally gone about its business has not only not helped us see important issues more clearly, but has actually kept us from seeing them at all. The discipline of Philosophy has busied itself with abstractions now structurally built into the discipline, abstractions that distance both its practitioners and all of us from what should be the real work of Philosophy, namely, to produce, as Wittgenstein said, ‘sound doctrines that change our lives’. (Wittgenstein’s Culture and Value (p. 53)). What Philosophers have become good at, instead, Diamond argues, is deflection: “I simply want the notion of deflection for describing what happens when we are moved from the appreciation, or attempt at appreciation, of reality to a philosophical or moral problem in its vicinity.” Or in Ian Hacking’s words: “We substitute painless intellectual surrogates for real disturbances.” The discipline engages its practitioners in difficult puzzles, then, exercises that deflect their – and our attention away from the real life problems we should be grappling with. Philosophers are good at grappling with the hard stuff. But the important hard stuff, the ‘difficulties of reality’ that all of us must 4 face are, in Diamond’s words, ‘shouldered out’. (Diamond, “The Difficulty of Reality and the Difficulty of Philosophy”, p. 58.) So Philosophy, defined by the three claims I have sketched, cannot help us see, grapple with, and ultimately act on, what Diamond calls ‘the difficulties of reality’. And no difficulty of reality demands more of us at present, we submit, than how we currently stand to animals. A different understanding of how to do Philosophy: So what is to be done? Does Philosophy have any role to play here? Is there any way to retain what is strong in Philosophy and have it still fill the role of helping us bridge the chasm that opens, in the hard cases, between conviction and action? Can Philosophy be a force in helping us stand differently to the animals we now allow to be factory farmed and used for food? Perhaps. Perhaps. But only, we submit, if we see the work of Philosophy as sometimes proceeding radically differently than it has come to proceed. Maybe good work in Philosophy needs sometimes (?always) to focuses less on theory and principle, less on the technical ‘new big term’ and more on our everyday concepts, those that teacher and student, speaker and audience, all share in our everyday lives. If we take that suggestion seriously, the work of Philosophy then becomes a project to develop our web of shared concepts, to explore the decisions and practices that flow from a careful exploration of where our values lead us. Arguments like Singer’s as well? Certainly. We struggle to present a new picture of the cannon, not trash it. New technical concepts? Perhaps. But all woven around the ways in which we and our audiences live and think about our everyday lives. The approach we suggest is not unique. Cora Diamond’s project in “Eating Meat and Eating People”1 and “The Difficulty of Philosophy”2 or Talbot Brewer’s work in The Retrieval of Ethics3, for instance, emphasize an exploration of the ways we all live with our concepts, and what such a careful exploration can reveal to us. For them, as for us, it is the exploration of how we do and might live with our concepts, rather than the construction of principle and theory, that constitutes their – and our - means of understanding, speaking about, and ultimately developing our moral lives. An authentic and we hope, less alienating image of Philosophy emerges when we follow this alternative, one that allows us to join novelists like Coetzee and essayists like Foer in creating the kind of project that might help all of us to act in accord with our values. Diamond, Cora (1991) “Eating Meat and Eating People”, The Realistic Spirit, MIT Press. Diamond, Cora (2003) “The Difficulty of Reality and the Difficulty of Philosophy”, Partial Answers, Vol 1, #2, pps 1-26 3 Brewer, Talbot (2009) The Retrieval of Ethics, Oxford University Press. 1 2 5 6