dissertation - Edinburgh Research Archive

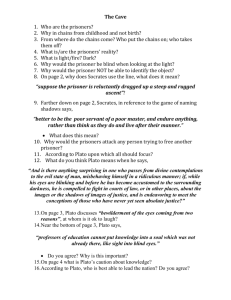

advertisement