continuing professional development

advertisement

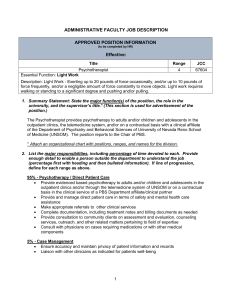

Ethics Workshop Creativity and Madness Santa Fe 29-30 July 2014 CONTINUING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT INTRODUCTION The stimulus of being alone with a patient creates the need to know more about psychotherapy. Psychotherapy is learned on the job, in the therapeutic relationship. The mental health professional in training has so much to learn. Though learning techniques of a competent psychotherapist in four years of training, it takes several more years to find the fit, the style, and the acquired skill to be comfortable and effective as a psychotherapist. I have mentioned the humane and warm presence of Elvin Semrad earlier in this text. Dr. Semrad was an extraordinary clinician and gifted teacher. Pietro Castelnuovo-Tedesco [1990] reminds us of Semrad’s style: “Dr. Semrad told us that if we wanted to learn about psychiatry, we should each buy a good suit with two pair of pants [he emphasized with his voice the word good] and then plan to sit with patients until we had worn through the seat of both pairs.” How long does it take to get a deep shine on a thinned out pair of pants? Ekstein and Wallerstein [1958] state the acquisition of “basic psychotherapeutic skills” are not enough to train the psychotherapist: “What would still be missing is a specific quality in the psychotherapist that makes him into a truly professional person, a quality we wish to refer to as professional identity.” In their discussion, Ekstein and Wallerstein cite the 1955 report of Lawrence S. Kubie proposing the title “medical psychologist” as an individual trained in psychodiagnostic and psychotherapeutic work. They add: “As long as Kubie’s call for a special grouping of psychotherapists is not heeded, and the indications in the present social structure are that it will not be heeded soon, the identification with psychotherapy as a profession will be merely part of a larger professional identity characteristic for today’s practitioners in this field.” This is the 1955 position. And who said the last century was marked by an urgency to get things done? Fragmentation in our approaches to patient care continues. Psychotherapy programs are disappearing off the menu of the academic plate of offerings. Professionals have great difficulty developing a psychoanalytic psychotherapy practice in this new century. Ekstein and Wallerstein (1958) add: “A Psychotherapy training program, as part of a general psychiatric residency program, must be devised in such a way as to permit a process in which ideal professional self-realization is possible, and in which freedom of choice exists, so that the young psychiatrist can incorporate into his professional self concept those identity aspects that will indicate to what degree he wishes to and is able to become a psychotherapist.” 1 Educational programs at the postgraduate level do not tolerate great flexibility. There are specific segments of programming based in various clinical services that are required. Electives are limited. Thus, clearing the educational hurdles and completing the postgraduate training program feels like the end of an era. Graduates feel a relief, out from under the apprentice role, and look forward to clinical practice. Graduation is an important step though it is really just the end of the beginning in developing ideal professional self-realization. THE BIRTH OF THE HUMANE PSYCHOTHERAPIST The observational research of Margaret Mahler [1975] that organized into “separation-individuation” theory has been of great value to me. I apply her work to an understanding of the learner in the psychotherapeutic process. Herein, I paraphrase the title of her 1975 report with Pine and Bergman, The Psychological Birth of the Human Infant. Mahler’s work lends itself to a description of the developmental process of the undifferentiated professional moving through postgraduate training. Let me refer to a 1994(a) paper by Gertrude and Rubin Blanck, “The Relevance of Mahler’s Observational Studies to the Theory and Technique of Psychoanalysis.” Rather than restate the rich description of the Blancks, I use extended quotes in the following two paragraphs, all taken from the 1994(a) paper without further reference. Central to Mahlerian theory is the description of mother-infant interaction and the bridge to my application of her theory in becoming a psychotherapist. There are parental figures in the learning environment especially with mentoring and supervision. Mahler delineates three preliminary phases after physical birth leading to “psychological birth” around three years of age. Let me highlight this discussion. After physical birth, there is the first phase “regarded as the time when neonate and mothering person try to find a comfortable fit in order to be able to enter the second phase, symbiosis.” Mahler, deriving theory from data, “concludes that symbiosis is an essential experience that orients the child to the world of reality.” She notes the ability to love and “the capacity for empathy” are linked to this developmental step and introduces the concept that “certain inborn capacities do exist.” The Blancks refer to the recent work of Emde confirming, “Mahler’s discovery that the individual unfolds within the matrix of the mother-infant unity and that the relationship between neonate and caregiver establishes enduring patterns, a matter of great importance to ego psychological object relations theory.” Subphases of the separationindividuation process “powered by an aggressive thrust in maturation of the physical self” give rise to a differentiation process, separating from the caregiver, in a practicing subphase where the individual reaches out to experience the world. This is followed by a rapprochement subphase in which there is a coming back together again with the caregiver. Interactional experience bears heavily on the outcome of these subphases as the developing individual moves to the final subphase, on-the-way-to-object-constancy, which if 2 completed competently, provides the structuralization necessary for psychological emergence and “full development of the capacity to engage in conflict.” For Mahler, separation and individuation are “two separate, but parallel tracks… the separation track is involved in negotiation between the developing self-representation as it works toward ever-greater independence from the object representations” while “the individuation track is more autonomous… far less bound up in conflict between the two sets of representations,” yet intricately bound to the right amount of separation and distance, availability and connection or intimacy, in each successive developmental step. During postgraduate training, one starts to grow an identity as a professional and learns to function in the most efficient, least conflict-bound position possible. If you consider the brief description of Mahler above, better still read the original sources, you may sense my proposed links to understanding the complex developmental process of becoming a psychotherapist. The undifferentiated professional enters postgraduate education. Can you recall the early days of your own learning experience? You had certain knowledge, understanding, skills, attitudes, and problem-solving abilities [which can be contrasted with the physical birth of the human infant] but struggled to find your fit with the new maternal environment, in this case, the clinical setting. The smiling response of the new professional at one month of age could be the dawning awareness of the link with the new mothering person although it could just be gas a temporary relief from tension. At about one month, having struggled to find the fit with the new specialty interest, there is a merging into a symbiotic phase, generally in the form of a mentoring relationship in which the learner seeks caring objects to sustain, nurture and inspire. At first there is simple imitation, a primitive incorporation as we try to swallow the whole object. Gradually, there is a building up of our internal mapping using introjects that align with our desired goal. Learners will select traits in the figures we gather around us as we transit through the educational environment. With experience and further ability to practice on our own, we become more sophisticated. Though looking for mentors to support and direct at each successive stage of development, we become increasingly selective as our own separation-individuation process unfolds in the educational matrix. As we learn new skills and experience mastery, we practice being on our own, yet want and need a responsiveness, someone to share our excitement, to help us label experiences and be available to steady us when we extend too far. During the rapprochement stage we proceed with further internalization, transitioning on-the-way-to-object constancy. This initial process takes three years, sometimes four, and like any “childhood” development is the base for entry into successive stages of growth and development. Completing our early work in this psychotherapeutic analogy to separation-individuation is the end of the beginning. There are new 3 developmental tasks challenging us. Each new task stimulates the repetition and reworking of earlier separation-individuation experiences. Bad learning experiences with inadequate mentoring and professional trauma carry into the future, as do the positive learning experiences. Cycling through successive stages of development in subsequent years of professional practice will reflect the impact of this early milieu “for better and for worse.” In psychiatry, and other mental health professional programs, the learner is alone with the patient early in training. Unlike the novice surgical resident who is the second scrub in surgery, the psychiatric resident sits alone with a distressed, often disorganized individual. The universal response to professional anxiety and inexperience is the need to know more. However, it’s a time of real trauma! Learners recount missteps in their own learning process, with early attempts to venture out being connected with panic. These discussions of war stories are usually done in private with trusted peers. The mentoring relationship, so important to professional socialization, is akin to the mothering figure in our educational family of learner siblings, father figures, assorted aunts and uncles and other significant adults. The work in our educational family is filled with confusing multiple transference reactions as each individual struggles to feel competent and to master the increasingly complex set of developmental tasks. As learners we attempt to soak up and integrate everything into our internal structuring of who we are and how we operate in this evolving world. From the first encounter with the patient we attempt to listen, to understand, to organize, to question data, define problems and formulate psychodynamics allowing us to probe in a deeper and inquiring fashion. Along with the occasional periods of mastery and panic, we experience distress, confusion and depression as part of the educational process. Experience as psychotherapists, as we develop a shine on our pants (in the Semrad sense), contributes to a fascination with the inquiry process, and the awareness of the need for further development. In an existential sense, the developing psychotherapist is always “becoming.” From the fitting together, and merging with the educational environment, one hopes the inborn capacity to inquire is not stamped out by authority figures, and the separation drive fuels an excitement within the learner in the surrounding educational environment. Entry into clinical practice is a further stimulus and supervision is an invaluable life-long aid to further learning and effective care. SEEKING OUT MENTORS Like the child longing for a response from an interested mother who can share our secrets and fantasies, we long for a mentor, preferably several if you please, to sustain and nurture us. Mentors and psychotherapy supervisors are not necessarily the same, in my opinion. Survival, balance and development of meaning within the “black box” of postgraduate education is dependent upon key individuals the learner selects within the educational environment. The mentoring relationships and supervisory contacts act as the lifeline for making it through the hazards of early training. 4 I recall a psychotic patient during my first year of training saying: “You even walk like him.” For me it was just another part of the patient’s thought disorder I labored to understand. During my third year of training, while still working with that patient, she clarified the comment made two years earlier, saying I modeled on my first supervisor’s clinical approach and listening attitude, imitated his behavior - even walked like him. I’m sure she was accurate. Jensvold [1994] describes “good mentoring, lack of mentoring, and bad mentoring that can occur as a condition of employment; a more senior person mentoring a more junior person by mutual choice; co-mentoring and ‘role model mentor.’” She notes “mentees are in a very vulnerable position” and emphasizes the importance of good mentoring in helping the individual “to become established professionally.” The mentoring relationship “formed by mutual choice and not dependency” seems on the face to be a desirable relationship, although it may mean that “credentials are dependent upon the continued relationship, or at least upon completion of the position” placing the mentee in a difficult position. Co-mentoring, in which “the people involved may be peers, or may differ somewhat in their seniority” seem to have the more positive outcome in which “both receive support and both careers are advanced.” Interestingly, we may have, in our modern day society, many mentors who have been role models, perhaps people not even met, but rather read about or studied. A common example would be Osler as the great mentor of so many future physicians, or Freud and his early disciples. A leader in a field may be admired from a distance and their professional persona adapted to the individual learner. The mentor is a compassionate intermediary, a transitional object between infancy and adolescence in our professional development. Bickel [1995] has noted: “Key to a successful career is a mentor, someone who acts as a guide, an advocate with regard to resources and who enduringly cares about a protégé’s advancement.” Just as the many vicissitudes in early personal development occur, so too in professional education. Learners are dropped in the water to sink or swim a traumatic entry to the swimming experience. In beginning psychotherapy and advancing one’s skills, we don’t jump into the consultation room without risk of injury to self and patient. Finding the delicate balance of structured preparation and balanced experience with the patient becomes a critical variable in teacher student interaction. Just as the successful patient extrudes the therapist from their life as they move out on their own, so too, the student leaves the teacher behind with maturation. The learning process unfolds. EDUCATIONAL METHODS Lectures, small group discussions, individual study, informal exchanges, interactions with patients, peers relationships, mentors, and supervisors, the shared insight of experiencing treatment first hand all are well traveled roads 5 to the deeper appreciation and developing ability to learn about and practice the science and art of psychotherapy. Anxious trainees read. Anxious learners attend case conferences, although not wanting to present one of their own patients. As we become desensitized to the clinical conference and find other people can make errors or sound as inept as we can feel, we start to share experiences with colleagues at the same level of training. During our middle years of postgraduate training, we struggle to get on top of new and intriguing cases, we watch demonstrations of psychotherapy and start to participate more actively in conferences. Toward the close of the training program, learners may compete to present at case conferences and seminars. The stimulation of the national meeting or specialized workshop observing and interacting with “national figures” read about in journals and texts is a great learning experience. Professional socialization is an important component of the developmental process. Toward the end of training, and throughout professional life, any opportunity to teach can provide a fine learning experience. When the teacher prepares a topic for presentation and attempts to involve the learner in the pursuit of their own education goals, the greatest gain falls to the instructor. It goes without saying that anytime you are asked to address a public group or a professional audience, you have the responsibility to present your material at the highest professional level. You do not have the luxury of “winging it” when you represent your professional colleagues and yourself in a public setting. As early learners with the greatest need to know more, we collect and collate all the bits of material from our educational universe, integrating knowledge, understanding, skills, and attitudes that fit with our developing internal map. The experience with the patient, combined with individual supervision, comprises the essential building block. Although it’s time consuming and sometimes feels inefficient, the one-to-one encounter between supervisee and supervisor remains the cohesive thread in the learning of psychotherapy. The individual supervision of the resident’s psychotherapy is probably the most important alliance the psychiatric resident has in training, with the probable exception of an analyst or psychotherapist encountered in one’s personal psychotherapeutic or psychoanalytic experience. Personal therapy or analysis? Should every resident have personal experience with his or her own therapy? A quotation attributed to the southwestern writer Edward Abbey comes to mind: “What is truth? I don’t know and I’m sorry I brought it up.” Psychoanalysis or psychotherapy may become the finest learning experience for the developing psychotherapist. One cannot put the emotional experience of being a patient into a series of words. Feeling the inquiry process within oneself, sensing the role of the skilled therapist or analyst at work, and experiencing transference and resistance, adds to the learning base of any psychotherapist. To feel the struggles, recall the emotions, and apply ostensive 6 understanding allows the fullest respect and compassion for the psychotherapeutic process and our patients. The personal therapeutic encounter provides meaning. Should personal psychotherapy or analysis be part of the postgraduate curriculum? I believe yes at the right time. Personal psychotherapeutic treatment should not occur as an elective early in training. There is quite enough going on at the beginning. Educators need to differentiate between the professional developmental process and the option of choosing personal growth in personal psychotherapy or psychoanalysis. If a learner is having difficulties that interfere with patient care or professional meaning, psychotherapy should be entered into without question. However, on the question of the option early in training, I am in agreement with Dubovsky and Scully [1990] from the University of Colorado School of Medicine: They state psychoanalysis and related psychotherapies can have adverse effects during the turmoil of residency training. Professional Identity Psychotherapists come from a variety of disciplines. We are no closer now to attaining Kubie’s desired medical psychologist than we were in the 1950s. There have been attempts to carve out separate pieces of professional turf in the behavioral sciences. During the last three or four decades there have been attempts to define a psychiatrist. See Langley and Yager [1988] for an update on one study. The stigma of mental illness combined with the advent of “managed” care has devastated professional training and clinical practice. The only area of professional life providing financial incentive at present is accepting increased administrative responsibility. There are limited funds for careers in research and educator training programs. Reimbursements for skilled clinical practice and community service activities are low. So how does the professional concerned about comprehensive individual care, including psychological medicine initiatives, maintain a sense of meaning and satisfaction? Fennig et al. [1993] note “there is inevitable conflict in connection with the issue of identity,” adding a growing number of (psychiatric) residents have begun to question the “necessity and relevance” of psychotherapy to their own training. Using Erikson’s definition of identity, Fennig et al. touch on issues of professional identity “built around various elements such as identification with mentors, the acquisition of a common professional language and body of knowledge, the mastery of certain skills, and finally, the attainment of recognition by society. The ultimate result of the process is the feeling of ‘this is me’.” Their discussion describes the basic principles of psychotherapeutic practice to be totally different from the educational experience in the medical school in which “the physician is a real person: encouraging, advising and giving concrete help in the form of medications or other kinds of treatment.” In contrast, psychotherapeutic physicians become participant observers, less likely to offer patients any direct concrete help such as advice or 7 encouragement, thereby entering a new field which could threaten a learned role of being socially responsible and an authority in the field. “We find that for some residents the giving up of the authoritative role, even for the duration of the psychotherapy session, is threatening and anxiety provoking… in psychotherapy, residents are more personally vulnerable because their selves and their personalities are the major vehicles of the treatment, therefore failure might be perceived as more personal. This kind of experience can be a source of confusion, frustration and anxiety for young residents as well as for more experienced psychiatrists.” Fennig et al. suggest residents should learn “seemingly contradictory aspects of identity can coexist successfully,” and emphasize confronting “this issue early in the training of residents and to provide a setting in which a positive professional identity can develop. Failure to do so can lead to frustration, anger, demoralization and devaluation, inhibiting optimal development of skill.” All around us we see evidence of commerce and merchandising. Competing hospital-based programs, commercials for the wonderful advances in managed care and the professional group providing the best care are on the television screen every night. The politicization of health care reform and the chronic shortfall in funding humane programs for vulnerable populations such as the homeless, the mentally ill and those existing in poverty leaves us frustrated and detached. Multiple marketplace forces rather than the needs of the patient have changed traditional practice. Traditional educational and practice models have disappeared. Acute illness requiring a reasonable inpatient hospital stay allows careful diagnostic evaluation and appropriate treatment interventions. Those days are gone! For better or for worse? How can a suicidal patient be evaluated and treated on an inpatient service with an average stay of 2.3 days? The external forces of financing and managed care have developed ambulatory outpatient programs with partial hospitalization, crisis clinics and medication clinics making brief treatment the one size that fits all the mentally ill. Appendix G continues the discussion of external forces changing clinical practice. How does this effect professional identity? I have seen and heard of demoralized health care providers. Large hospitals, competing for their share of the mental health dollar, have continued to decrease the length of stay with high turnover maintaining occupancy rates. The outsider sees a vicious cycle with appropriate inpatient care and long-term therapy being squeezed out of contemporary practice. A physician can make a psychiatric referral and the “evaluation” is done without the patient seeing a psychiatrist. Perhaps a psychiatrist will consult for a fifteen-minute segment to prescribe a medication, after the selective screening by a non-psychiatric mental health professional who has defined the problems. There have been many lawsuits for wrongful death and inappropriate treatment in the new management models. Results of these negotiated legal actions are confidential with lawyers warning parties that revealing any details of a settlement may void the agreement. 8 Ethical practice of one’s profession gets tougher every year with each new restriction. The costs of care have increased and the usual market forces do not operate in sickness or in Health. Everyone wants the latest advance in diagnosis or treatment. Should a child be deprived of a life-saving bone marrow transplant when the parents cannot pay for the procedure? Do we let someone die because the intensive care needed goes beyond the limits of their insurance carrier’s decision? I do not have great wisdom here. I have the dilemma you confront everyday. Who am I? What do I stand for in this situation? A double agent? Am I the patient advocate, the defender of the system, or what? What is the cost in professional identity with a system of care selecting out, or squeezing out, high-risk patients into the public sector, already overburdened and underfinanced? If you are not the patient advocate in the system, who will be? In data derived from the Duke University Epidemiological Catchment Area Project, Landerman et.al. (1994) found psychiatric disorder with a specific DSM-III diagnosis was the more powerful predictor of a mental health visit when contrasted with the availability of mental health coverage. Landerman et al., conclude “findings suggest that attempts to reduce expenditures by limiting the number of psychotherapy visits would reduce care among those still in need once these limits were exhausted and coverage was denied.” The focus on the patient is lost in discussions of the delivery system. In 1970, I saw a manual of the leading insurance company of the day, entitled How to Deny Claims. The manual was more than two inches thick. How thick is it now? Discrimination against patients with psychiatric illness is common practice. These changes go beyond our specialty to influence the physician/patient relationship. The interested reader might turn to Emanuel and Dubler [1995] who note: “The expansion of managed care and the imposition of significant cost control have the potential to undermine all aspects of the ideal physician/patient relationship. Choice could be restricted by employers and by managed care selection of physicians; poor quality indicators could undermine assessments of competence; production requirements could eliminate time necessity for communications; changing from one to another managed care plan to secure the lowest cost could produce significant disruption in continuity of care; and use of salary schemes that reward physicians for not using medical services could increase conflict of interest.” The impact on clinical practice and the educational milieu is alarming. Traditional models are disappearing in the teaching and learning of psychotherapy. An unprecedented attack on psychotherapy, despite the consumer’s statement that it helps, has led managed care advocates to petition Curriculum Committees for time in the training schedule so learners can be properly initiated into the new models. Apart from the reality of a decreasing 9 number of training programs, the prevailing approaches to treatment are medication for severe disorder and brief counseling for crisis. Unfortunately this model merges with the whole field of disorder leaving inappropriate care and under-treatment the depleted remainder of the usual and expected standard of care in most sectors of society. Recently another unacceptable clinical practice within managed care came to my attention. Selected patients in a specific program, while in hospital treatment, received a letter stating their insurance plan and their attending physician had reviewed the services being provided in hospital and determined further inpatient care was not needed. This letter was sent without review or comment by the attending physician and signed by a “Medical Director” no longer in that position. This is another intolerable action, by persons unknown within the administrative structure, who take action interfering with care, adding a threat of discontinuing care frightening the patient. Of course the patient can appeal the decision legally through a complicated process, but in the meantime, continues hospital services at personal expense or leaves the hospital before receiving appropriate continuing care. The physician and patient should be able to determine what is best for the patient. Such abuses are quite familiar to the practicing psychotherapist, devastated by the cuts in clinical services to the mentally ill. Management determinations reducing necessary care will not be sustainable for much longer. In the meantime, the psychotherapist remains focused on therapeutic connections and therapeutic goals that help the patient through this difficult era in healthcare delivery. How long can this erosion of professional identity continue without leaving the practitioner depleted and vulnerable to professional (burnout) stress syndrome? Though my crystal ball is as difficult to read as yours, the reversal of this depleting process is closer than we realize. The patient-focused inquiry will require your attention and will oblige a new and innovative approach to comprehensive care. Study of your clinical effectiveness will sustain you and continue to strengthen your working alliance with the distressed and disordered patients seeking your professional care. Consumers will require change and government will develop initiatives to restore humane care. TOWARD YOUR CONTINUING EFFORT Consecutive generations of therapists have been fascinated by the gains of our patients. In 1934 James Strachey published a classic paper on “The Nature of the Therapeutic Action of Psychoanalysis” expressing concern about the dearth of literature on “the mechanisms by which its therapeutic efforts are achieved” and “remarkable hesitation in applying these findings in any great detail to the therapeutic process itself.” The Fourth Edition of the Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, edited by Allen E. Bergin and Sol L. Garfield (1994) and the 1995 publication of Research In Psychoanalysis: Process, Development, Outcome edited by Shapiro and Emde summarize research findings and emerging questions over the decades since Strachey’s comments. Recent clinical research efforts continue painstaking work yet fail 10 to capture the essence of the treatment experience that any psychotherapist, as a patient in analysis, “knows” has added to their life. As the King of Siam addressing Anna in The King and I says, “It’s a puzzlement.” The complexity of designing controlled research protocols in psychoanalytic psychotherapy remains one of the “puzzlement” factors. Research efforts documenting the efficacy and cost effectiveness of psychotherapy are appearing. The clinician’s study and research begins with a single case. Experienced therapists seem to have learned “things that work” yet do not discuss their strategies openly. How does the learner gain and add inquiry to the “puzzlement”? Strachey (1934) states the analyst “offers himself to his patient as an object and hopes to be introjected by him as a super-ego... introjected, however, not at a single gulp and as an archaic object, whether bad or good, but little by little and as a real person.” Thomä and Kächele (1987) describe this process as “symbolic internalization.” Often on entry to therapy the “one gulp” approach seems to operate. The desperate patient says, “Just tell me what to do Doc.” Though resisting the invitation to take over, the therapist may offer comment, advice and suggestions that pull the patient back into the therapeutic focus. A question from an objective outsider, reflecting on what has been said, can have a powerful impact on the patient. Discussion, sometimes confessional in nature purging the system, powers a reawakening of the individual’s conscience structure and alignment with the therapist has a quality of shoring up super-ego functions. With Anna Freud’s 1936 publication of The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defense and Hartmann’s 1939 publication of Ego Psychology and the Problem of Adaptation the field opened for theoretical advances later known as ego developmental psychology. This field of study has developed quickly. We now understand the real interaction between therapist and patient involves a sophisticated integration process at all levels of the patient’s functioning. As each new theoretical advance is integrated into our therapeutic approaches, the dynamic forces of the therapeutic encounter grow more impressive. One of the recent additions to our understanding involves the intersubjective perspective developed by Robert D. Stolorow and George E. Atwood. See Orange, Donna M. George E. Atwood and Robert D. Stolorow (1997) for their work on the context of the therapeutic connection. The flexibility and openness to change, that the dynamic interaction with the patient teaches, applies to our own developing professional identity. Continuing inquiry is at the core of the dynamic psychotherapist and rules out a rigid adherence to one theoretical position to fit all patients and clinical encounters. The century ahead will have a faster pace of development in theory and practice of psychotherapeutic approaches to human behavior. The integration of new biological findings, especially the unfolding studies of the brain and genetics, requires an ability to add to our humane and comprehensive approach to clinical practice and research. The patient-focused inquiry remains in place amidst our scientific advances. 11 The patient’s degree of structuralization with the accompanying needs, requirements and wishes will be the major determinate of how much is absorbed and integrated in treatment efforts. There are (and will be) limits to what the ‘good enough’ therapist can do, limits generally determined by the developmental level of the patient. The capacity of the patient to extract from the therapeutic interaction will be a major variable in determining outcome. The patient has to be able to use the treatment situation to assist their development. In turn, the therapist has to ensure that he or she does not intrude on that important work by the patient. In 1919 Freud pays homage to the patient’s ego fusing “into one all the instinctual trends which had been split off and barred away from it. The psycho-synthesis is thus achieved during analytic treatment without our intervention, automatically and inevitably.” By extending ourselves we help the patient to do their own healing, to resume their own development. We try not to interrupt a natural activity once the patient has understood the resistances. Paralyzing disorganization is handled step-by-step. Anxiety and depression are used as an adjunct for development, providing a psychological “barometer” of the internal environment suggesting more work is necessary. When the conditions for further growth and development are established we have to step back and allow the patient to handle their own treatment. Attunement emerges as a key factor in the interaction. The patient must reveal issues and the therapist must hear, see and feel those issues of the patient, if there is to be a shared experience. Like the affective attunement of a good enough mother linking with the infant and child, the therapist’s ability to participate in the world of the patient allows the patient to sense he or she is heard, perceived as a real person, confirming there is validity to what they have experienced. This requires an availability of the therapist. We feel good after a session when this kind of attunement occurs. We question why it does not occur at other points. To be attuned, the therapist must work to leave bias, preconception and intellectual knowledge behind, to inquire rather than judge in the communication of the patient’s raw material. We balance our affective attunement and intellectual skills to help the patient see things in a different way; to ask questions when we do not know the answers; and to maintain the “holding environment” while the patient is reframing experiences and redirecting their energies. In the patient-focused interaction, communication becomes the important vehicle for therapeutic change. As the neutral outsider, becoming the stimulus for the therapeutic interaction, the therapist becomes a new object for the patient, a consistent and predictable object. The reliable, steady and real qualities of the patient-therapist encounter allow the patient to shape what is needed for further growth and development. Perhaps the most important value of our “school of thought” is the potential for improved communications. Jerome Frank (1973), quoted in Strupp and Binder (1984) states: 12 “While the contents of schemes and the procedures differ among therapies, they have common morale-building functions. They combat the patient’s demoralization by providing an explanation, acceptable to both patient and therapist, for hitherto inexplicable feelings and behaviors. This process serves to remove the mystery from the patient’s suffering and eventually to supplant it with hope.” One critical element of a professional approach to the distressed patient is staying in focus. The problem definition in our developing understanding of the patient’s patterns allows us to maintain a central focus, to bring together diverse productions of the patient and link the here-and-now with the past then-and-there experience of the patient. The therapeutic interaction is the meeting place for all parts of the self, with the therapist attentive to helping the patient clarify their direction. “How does this apply to getting you where you want to go?” can be a question returning the patient to the therapeutic focus. As the therapist stabilizes and supports the patient, we assist movement toward a flexible, moderate and tolerant position on matters. Rather than the black and white, all or none style that characterizes many distressed patients, the therapist listens respectfully and raises questions that suggest compromise, negotiation and middle ground on life choice during transitions, decisions in line with internal values and goals. In the process therapists hear of almost unendurable sadness our patients can experience. We marvel at the resiliency left after major trauma. Greenacre (1975) says: “It is the relation between analyst and analysand that makes the nearly absolute truth tolerable and in some ways acts as a catalyst for healing to take place.” Since Freud’s early writings we have known the forces of resistance and the enactments of transference-countertransference must be understood by the patient and therapist. Interpretation has been the defining characteristic of psychoanalysis for decades. We learn to understand interpretation leading to insight is not always enough to produce change however. Pulver (1992), an advocate of insight being “crucial to psychoanalytic change” notes: “The search for a single mechanism of psychic change is doomed to frustration.” Insight without changed behavior has heuristic value but will not be enough to sustain a therapeutic relationship. The therapist’s understanding of the patient, no matter how brilliant the insights may be, does not create change if not integrated into new strategies put in play by the patient. Schwaber reminds us of the discovery process, inviting the patient to seek answers rather than giving outside directives. “Interpretation is a shared act” (Schwaber, 1990b). The therapeutic focus shared by patient and therapist is woven into the fabric of change. BEYOND THE CONSULTATION ROOM One of my valued learning experiences was in 1966 at the Medical Center of the University of Illinois in Chicago with a group of twelve international educators studying research in medical education. The first book I read in the 13 program was Self-Renewal: The Individual And The Innovative Society by John Gardner. My clinical experiences in psychiatric training at the Institute of Living in Hartford, Connecticut and my developing vision of educational innovations merged as I read, “The ultimate goal of the educational system is to shift to the individual the burden of pursuing his own education.” Though I had known the burden first-hand, there was a sudden insight about this burden at the core of self-development, the stimulation of inquiry fueling growth and development and what is called scholarship in later years. When my work shifted in 1967 to the new medical school in New Mexico, the people, setting and challenges in the “Land of Enchantment” became the fabric of life, a merger, fit, and commitment. Over the past 47 years, working within our culturally diverse communities, my clinical and social concerns lead me to new strategies on broad societal challenges. When socioeconomic factors, instability of the family, geographic moves, migration, competition with older and stronger siblings, the inability of a parent to provide psychological closeness, sickness and social withdrawal create a gap in early growth and development, children can arrive at the prekindergarten level already scarred by deprivation though still hungry for the experience of a loving and available teacher. The interaction with a responsive adult can revive a child’s instinctual drive to reach out and interact, to get what is needed, to gain strength and gratify instinctual needs. Memories of a warm and loving teacher or mentor remain with us for a lifetime. And when continuing difficulties rule out positive corrective experiences, childhood loss and gaps in self-development leave an imprint on each successive day. The burden of pursuing education may seem out of reach. By working with colleagues in different fields, integrating the shared experiences and resources of concerned individuals and organizations in New Mexico, I see opportunity to change our situation. I need to join the thousands of concerned citizens and hundreds of organizations working for a better place for our vulnerable individuals, families and neighborhoods. I intend to focus on individualized attention for children within vulnerable populations, energizing youth, and renewing the community-based supports to sustain change. My commitments include: develop a one –to-one mentoring and tutoring program available to every child at risk in New Mexico fuel the community reinvestment of bright and inspiring college student mentors as our future leaders and integrate fragmented community efforts into a shared responsibility for the New Mexico educational experience crucial to improved quality of life for all. The current report of the Annie Casey Foundation presenting state by state evidence combining education, employment, income, health, poverty and youth risk factors placed New Mexico in 49th place in 2012, and in 2013 we have moved to 50th place. There is only one direction to go now. 14 If we do not grow creativity, resilience and trust, fuel confidence and scholarship, the failing individual and family may not be able to identify or express the need for help, despair giving way to social withdrawal and lost opportunity for renewal of positive life force. When unrecognized or not reversed, the path to failure becomes a pattern of negative adjustment. A prior option for those below proficiency used to be “well at least there’s the army.” No longer! The American military reports 75% of applicants cannot enlist because they have not graduated high school, have criminal records or are physically unfit. Costs of social disruption in the classroom, the increasing budget for youth in the criminal justice system, the lowered income of the individual failing in the system and the loss of vital and creative people in society seem incalculable. Though the future of America rides on present and successive generations of our children, we continue to lose ground with an erosion of values and fragmented thrusts to fix the educational system. WHEN YOU RETURN TO WORK Clinical experience and professional development form a fabric of change for the continually evolving psychotherapist. You cannot be a spiritualist who never gets lost because you do not know where you going. Being grounded is at the core of your developing professional competencies. And it starts with your theoretical positions, routines and competencies. Best wishes to you. Respectfully, John R. Graham, MD abqparadox@comcast.net 15

![UW2 - Psychiatric Treatments [2014]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006859622_1-db6167287f6c6867e59a56494e37a7e7-300x300.png)