Summary of the Debate for American Independence

advertisement

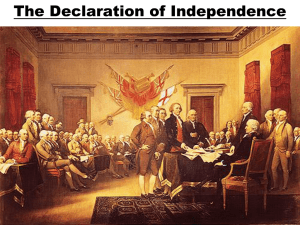

Summary of the Debate for American Independence Thomas Jefferson provided an excellent summary of the debate over independence in the Continental Congress. Delegates were split in how they wanted to respond to Britain When the Continental Congress met in June 1776, it was by no means assured they would declare independence from Great Britain. Most of the middle colonies were against independence or at least against it at that time, while the southern colonies and New England were for it. Indeed, war with Britain was already underway in New England. On May 15, 1776, the Virginia legislature had instructed their delegate to push for independence. Consequently, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia introduced a resolution on June 7, 1776: that the Congress should declare that these United Colonies are and of right ought to be free and independent states; that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the state of Great Britain is and ought to be totally dissolved; etc. Arguments in Favor of Independence Thomas Jefferson made notes of the arguments that took place after this resolution was proposed. John Adams, Lee, and George Wythe, Jefferson wrote, led the arguments in favor of independence. Jefferson summarized these as follows. The Colonies were already independent from Britain, had been for a long time, and the question was not to state something new but “whether we should declare a fact which already exists;” Colonial allegiance to the king had always been voluntary, and that the war presently being made by the king and Parliament resulted in the colonies being “out of his protection; and by his levying war on us…long ago proved us out of his protection….” If the colonists were out of the king’s protection, then they were also out allegiance to him. Only two of the colonies, Pennsylvania and Maryland, were divided on the issue, but that they had not instructed their delegates to vote against it, but merely reserved the right of their legislatures to disagree with how their delegates voted. The people, in general, were for independence, as was demonstrated in how they responded to news of Virginia’s legislature voting for independence, and were looking to the Congress to lead the way. Foreign nations, especially France and Spain, would treat the colonies fairly and help them to win their independence. Unless a declaration of independence was made, colonial vessels would not be welcome in European ports. Waiting some months for perfect unanimity, “since it was impossible that all men should ever become of one sentiment on any question.” Arguments Against Independence The main debaters against independence were James Wilson, Robert R. Livingston, Edward Rutledge, and John Dickinson, with others joining. Jefferson summarized their arguments are follows. The timing wasn’t right; additional time was needed to deal with Great Britain; The people were not yet for it. The middle colonies especially (Delaware, Pennsylvania, New York, Maryland, and the Jerseys) were not yet for it, and additional time was needed for popular opinion there to take its course. Some of these colonies might secede from the Union if independence was declared, to the great disadvantage of the Union in dealing with European nations. France and Spain were not assured to support independence for the colonies. Although they were traditionally hostile to Britain, they might be more fearful of a strong and independent America. They should wait until the current military campaign was resolved. A victory for the colonies would strengthen their hand in dealing with the European nations. Before declaring independence, terms of how the colonies would be allied and governed should be set. Jefferson’s somewhat bland summary of the debate gives no hint as to which side was stronger. His position is known, of course, as a result of him being on the committee to write a declaration of reasons for independence and being called upon to write the draft. Despite his position, Jefferson did not disparage the arguments of those against independence. He seemed to understand their arguments and the merits of them. Jefferson feared division among the delegates, many who would support independence but preferred continued allegiance with Britain: “The pusillanimous idea that we had friends in England worth keeping terms with still haunted the minds of many.” This caused many minor changes to be made in the draft Jefferson wrote, as well as one major: "The clause...reprobating the enslaving the inhabitants of Africa was struck out in complaisance to South Carolina and Georgia." The end result is known, with the passage of the resolution on July 2, 1776, and the actual Declaration of Independence “was agreed to by the House” on July 4, 1776. Source: The Life and Letters of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Henry Augustine Washington; pub. Edwards, Pratt and Foster, 1858; pages 12-17.