STUDENTS WITH DISABILITIES AND ELL CLASSMATES English

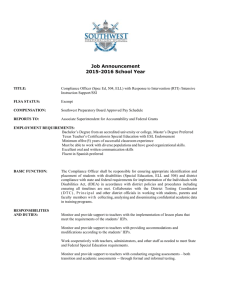

advertisement