Word - El Centro College

advertisement

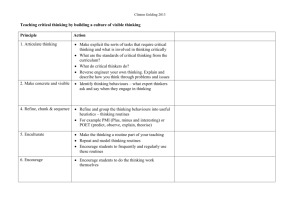

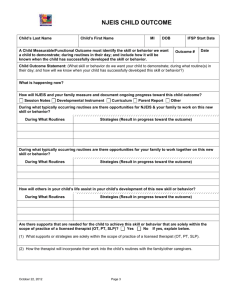

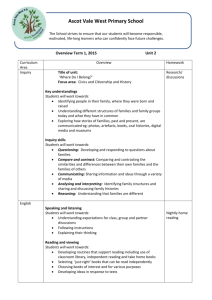

Tool Kit Activity : SLO #: 5 Tier: Pre-Core (1, 2, 3, 4 or 5) Suggested Class Time : 10 min. Complexity Index: Snapshot (PreCore, 1000, or Soph) Snapshot: 10 minutes of class, minimal instructor preparation Easy: 1 day of class, some instructor preparation Moderate: 1 – 2 weeks of class; some instructor training/preparation Complex: 1 – 2 months of class or wholly integrated into class, instructor preparation should start one semester prior to implementing In CT3, critical thinking is defined as: …the disciplined and continuous process of asking the right questions and practicing logical thought processes to come to justifiable conclusions CT3 SLO statement: Students will be able to implement continuous improvement in thought processes through reflection. Title Contributor(s) I Used to Think…But Now I Think… Mwauna Maxwell Learning Framework Faculty mmaxwell@dcccd.edu Objective of Activity: This “thinking” routine helps students to reflect on their thinking about a topic or issue and explore how and why that thinking has changed. It can be useful in consolidating new learning as students identify their new understandings, opinions, and beliefs. By examining and explaining how and why their thinking has changed, students are developing their reasoning abilities and recognizing cause and effect relationships. This routine can be used whenever students’ initial thoughts, opinions, or beliefs are likely to have changed as a result of instruction or experience. (Ex. after reading new information, watching a film, listening to a speaker, experiencing something new, having a class discussion, at the end of a unit of study, and so on) Activity Description: Explain to students that the purpose of this activity is to help them reflect on their thinking about the topic and to identify how their ideas have changed over time. For instance: When we began this study of ________, you all had some initial ideas about it and what it was all about. In just a few sentences, I want you to write what it is that you used to think about_________. Take a minute to think back and then write down your response to “I used to think…” Now, I want you to think about how your ideas about __________ have changed as a result of what we’ve been studying/doing/discussing. Again in just a few sentences write down what you now think about ___________. Start your sentences with, “But now, I think…” Have students share and explain their shifts in thinking. Initially, it is good to do this as a whole group so that you can probe students’ thinking and push them to explain. Once students become accustomed to explaining their thinking, students can share with one another in small groups or pairs. Web Pages for Instructor Preparation for Activity: http://pzweb.harvard.edu/vt/VisibleThinking_html_files/03_ThinkingRoutines/03c_Core_routines/UsedToThink/UsedToThink_Routine.htm Web Pages to Access During Activity: none Suggested Assessment Technique(s): Collect Individual Written Responses and score: Level/ Score 4 Category Description Advancing Thinker -The student demonstrates a clear commitment to reviewing decision making processes and conclusions. -The student explicitly states how he/she plans to use “improved” thinking skills to help make future, personal decisions. 3 Practicing Thinker -The student identifies personal experiences with decision making and the desired or undesired outcomes. -The student states an awareness of personal thinking practices (“I used to think…”) and feasible methods for self-improvement in those practices (“Now I think…”). 2 Beginning Thinker -The student is able to cite situations in which a flawed thinking process may have contributed to a poor conclusion/solution. -The student recognizes thinking practices exhibited by others and acknowledges a path for improvement. 1 Early Thinker -The student does not recognize problems in thought processes. -The student adheres to status quo methods to tackle issues/problems and opposes improvement. Bibliographic References: Activity Borrowed From: Harvard Project Zero http://pzweb.harvard.edu/vt/VisibleThinking_html_files/03_ThinkingRoutines/03c_ Core_routines/UsedToThink/UsedToThink_Routine.htm Thinking Routines Definition and Criteria Thinking Routines. Procedures, processes, or patterns of action used over and over in the classroom to activate and direct mental action. In order to be considered a thinking routine the practice should: - Be made up of only a few steps that are easy to learn and teach - Be easily scaffolded or supported by others - Be used over and over in the classroom - Have as its primary purpose a broader goal (like understanding) rather than as end in itself Another Definition: “A thinking routine is a thoughtful action done again and again that builds up a disposition or habit of good thinking.” -- Clinton Golding These are all thinking routines: KWL (Know - Want to know - Learned) See - Think - Wonder What makes you say that? I Used to Think. Now I Think. QFT (Produce - Improve - Prioritize) Key Ideas for Developing Intellectual Character IN THE CLASSROOM: THINKING ROUTINES • The Form and Function of Routines. Classrooms are dominated by routines for accomplishing housekeeping chores, securing classroom management, facilitating discourse, and directing learning. Such routines are explicit and goal-driven. For these routines to be effective, they usually consist of only a few steps, are easy to learn and teach, can be scaffolded or supported by others, and get used over and over again in the classroom. • Criteria for Thinking Routines. Although thinking routines often can be characterized as learning or discourse routines, the converse is not always true. Some routines for guiding learning are far from thinking-rich and do little to engage students mentally. First and foremost, thinking routines must activate and help direct students' thinking. Because this thinking is not necessarily the goal but usually a means to a larger purpose such as understanding, we say that thinking routines are more instrumental in nature. In addition to the criteria for other types of routines, good thinking routines must also be useful across a wide variety of contexts and be able to operate as both public and private practices. • Some Examples of Thinking Routines. Many familiar classroom practices and instructional strategies can be thought of as thinking routines if they are used over and over again in a way that makes them a core practice of the classroom. For example, KWL (What do you know? What do you want to know? What did you learn?), brainstorming, pushing students to give evidence and to reason by asking them “Why?”, classroom arguments or debates, journal writing, questioning techniques or patterns that are used repeatedly, and so on. • Thinking Routines as an Enculturating Force. Thinking routines act as a major enculturating force by communicating expectations for thinking as well as providing students the tools they need to engage in that thinking. Thinking routines help students answer questions they have: How are ideas discussed and explored within this class? How are ideas, thinking, and learning managed and documented here? How do we find out new things and come to know in this class? As educators, we need to uncover the various thinking routines that will support students as they go about this kind of intellectual work or enact new ones if such routines are not readily in our practice. Ron Ritchhart. Intellectual Character: What It Is, Why It Matters, and How to Get It (The Jossey-Bass Education Series) (Kindle Locations 1473-1477). Kindle Edition. Thinking to Understand “…are there particular types of thinking that serve understanding across all disciplines? Types of thinking that are particularly useful when we are trying to understand new concepts, ideas, or events?” Ron Ritchhart and colleagues David Perkins, Shari Tishman, and Patricia Palmer developed a list of eight thinking moves that they assert are integral to “understanding and without which it would be difficult to say we had developed understanding: 1. Observing closely and describing what’s there 2. Building explanations and interpretations 3. Reasoning with evidence 4. Making connections 5. Considering different viewpoints and perspectives 6. Capturing the heart (or core of a concept, procedure, event or work) and forming conclusions 7. Wondering and asking questions 8. Uncovering complexity and going below the surface of things” “While these eight represent high-leverage moves, it is important to stress that they are by no means exhaustive.” Thinking to Solve Problems 1. “Identifying patterns and making generalizations 2. Generating possibilities and alternatives 3. Evaluating evidence, arguments, and actions 4. Formulating plans and monitoring actions 5. Identifying claims, assumptions, and bias 6. Clarifying priorities, conditions, and what is known” Again, these six are not meant to be exhaustive. Ritchhart, R., Church, M. & Morrison, K. (2011). Make thinking visible. San Francisco, CA: JosseyBass, 11 – 15. TOPIC: ________________________________________________________ I used to think… But, now I think…