Old Donation Episcopal Church in Virginia Beach Ceremony

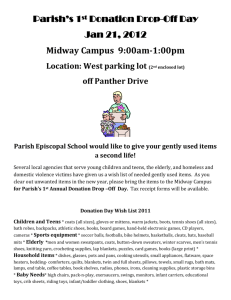

advertisement