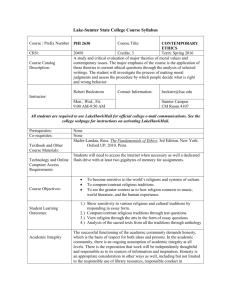

CULTURES OF COMPARISON AND TRADITIONS OF

advertisement