this chapter

advertisement

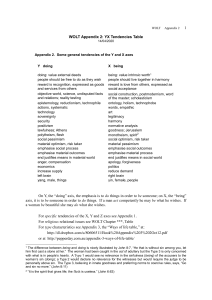

WOLT Ch 7 Exploratory examples 7-1 CHAPTER 7 EXPLORATORY EXAMPLES 9/02/2016 3900 words The axial structure applied to four well-known academic distinctions reveals their mistakes and extends them, showing their fit to everything else in the social universe. CHAPTER 7 CONTENTS 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Kant’s ends: price and dignity.......................................................1 Kissinger’s upheavals: conqueror and prophet .............................2 Hirschman’s exit, voice and loyalty ..............................................5 Process justice: adversarial, inquisitorial and restorative .............7 Conclusion...................................................................................10 References to Chapter 7 .............................................................. 11 1. Kant’s ends: price and dignity A famous assertion: In the realm of ends everything has either a price or dignity. Whatever has a price can be replaced by something else which is equivalent; whatever is above all price, and therefore has no equivalent, has dignity. (Kant 1949 [1785]: 182) Propositional logic says that where there are two propositions there are four truth values. If price is labelled Y and dignity, X then the four truth values are Y not X, both Y and X, X not Y, neither Y nor X. The four, numbered 1 to 4, may be set out as in Table 7.1. Table 7.1. Human nature, trust, YX Price Y Yes No 1 2 4 3 No Yes Dignity X Do the labels 1,2,3,4, fit with the WOLT four? Surely: 1 (Y not X): In an ideal competitive market everything has a price and there is WOLT Ch 7 Exploratory examples 7-2 nothing that cannot be replaced by an equivalent. It may be an exaggeration to say 1s would sell their grandmothers (for Type 1s are big on “family values”—see Chapter 3 §3) but any constraint on trade in the name of dignity will disguise compulsion and unearned privilege. 3 (X not Y): Love of money is the root of all evil. Putting a price on everything gives some people power over others, wrecks social cohesion and destroys the environment. Trees, for example, have dignity and should be hugged, rather than killed for profit. 2 (both Y and X): Rank and honour cannot be bought with money—that is corruption—yet money or its equivalent is essential as the measure of rank and to ensure decorum and authority. In regard to questions pertaining to the commercialisation of grandmothers and trees, these may be resolved with resolute and goal-oriented action, specifically by establishing a suitably qualified investigative committee with terms of reference authorising it to conduct a comprehensive inquiry and empowered to recommend the appropriate procedure in accord with the applicable guidelines. 4 (neither Y nor X): Kant’s pretentious distinction is irrelevant to a capricious world where you have to take what you can get when it’s going. So the four truth values are the WOLT four and Kant’s distinction fits on the Y and X axes and is connected to identity, freedom, justice, trust, risk, luck, etc, etc. It is thereby promoted from an isolated assertion by a respected philosopher to what looks like the hinge of all ethics. Ethics, it seems, ultimately boils down to two opposed positions. The countless connections display the irreconcilable nature of this basic X-Y ethical conflict as well as demonstrating the genius of the reconciling mechanism: the Z axis and 2-ism. 2. Kissinger’s upheavals: conqueror and prophet According to Henry Kissinger (1999: 1075), “change is the law of life” and upheaval is symbolised by the conqueror and the prophet: But the more abrupt the upheaval, the less reliance there can be on consensus. Force must replace a sense of obligation. Victory is prized over continuity; opponents are eradicated, not persuaded. The great symbols of this attitude are the conqueror and the prophet. The conqueror makes no secret of his design; his mission is to impose his will, though if his WOLT Ch 7 Exploratory examples 7-3 conquests last, he must sooner or later transform dominance into a sense of obligation. This is how empires achieve legitimacy. The prophet’s role is more subtle. Though his cause is based on proclaimed values, his claims are for this reason even more universal and insistent. Righteousness is the parent of fanaticism and intolerance. Opponents are extirpated—often, it is alleged, for their own good. Reigns of terror become necessities, not aberrations. The symbol of such a period is the commissar who kills millions without love and without hatred in the pursuit of abstract duty. This is why crusades have often created as much havoc and suffering as conquest. Two propositions yield four truth values. If conqueror is Y and prophet is X, then the four truth values are Y not X, Y and X, X not Y, neither Y nor X. The reader may take a pencil and write conqueror and prophet onto the Y and X axes of Table 7.1 because the four truth values straightforwardly fit the four WOLT types: 1 (Y not X): The conqueror is the extreme form of the competition winner. The prophet’s values would only get in the way. (Free marketeers would not shy from conquer to describe a market victory or killing.) 3 (X not Y): Values are eternal and the might-is-right conqueror is proof of the menace of power differentials. 2 (both Y and X): Kissinger says that if the conquest is to endure and be legitimate, obligation has to replace dominance.1 Obligation, though, relies on values—which Kissinger attributes to prophets. The replacement will be partial as conqueror strength must be retained in case the feeling of obligation to prophet-values wavers. 4 (neither Y nor X): Attempts to conquer or to impose values are foolish and pointless however ingratiation with the powerful is always wise. This especially applies in times of upheaval, for with the conqueror there will be booty; with the prophet the revolution will bring a better society (as long as the politically unsound are extirpated). So Kissinger’s terms fit on the Y and X axes and the conqueror, who he says later transforms dominance into obligation, is actually a Kissinger’s transformation of Type 1 conquest into Type 2 legitimacy is well known in political science as Mancur Olson’s (1993: 567) image of a shift from a “roving bandit” of indiscriminate theft to “a ‘stationary bandit’ who rationalises theft in the form of taxes.” 1 WOLT Ch 7 Exploratory examples 7-4 separate type who is combining some aspects of both his types—and of course, WOLT adds the fourth type Kissinger is unaware of.2 At a time of upheaval the 4s would play a bigger role than in normal times since their support would be more important to the other types’ struggle. Who would see a connection between Kant’s price and dignity and Kissinger’s conqueror and prophet? On the face of it they have nothing to do with each other yet WOLT shows that the mindsets are the same. The general lesson from this is that if someone makes a persuasive case for a distinction between two things then WOLT may be used to check it. If it works out, then WOLT will expand it to four options, clarify it, make it more precise, and connect it to the rest of the social universe. Unwittingly, Kant and Kissinger are complying with an underlying law. Though they are not by any means talking of the same thing, their propositions occupy a common cognitive framework. 2 Kissinger is a historian and was US Secretary of State under Nixon. He is himself a strong Type 2 (and an admirer of Metternich) and in saying “change is the law of life” he is pointing to an endemic failing of 2-ism: an inability to change. The far-sighted conservative permits social change in order to head off a potentially explosive build-up of grievances. Good examples are Bismarck’s introduction of health insurance and universal male franchise and Disraeli’s introduction of the franchise. In Burma the generals appear presently (2014) to be following this model. But such examples seem to be rare. Often overdominant 2-ism is sclerotic and power-holders protecting their privileges opt for repression rather than measured change, with the result that the eventual change is a traumatic upheaval. In 1776 the “father of conservatism,” Edmund Burke, urged that the American colonies be permitted independence but the government paid no heed. In Russia and China prophets Lenin and Mao displaced decayed 2-ist regimes (followed by vast extirpations—presumably Kissinger has them in mind) and in 1979 a prophet took over Iran. In Cambodia, prophet Pol Pot took over in 1975 and after horrific extirpation, a foreign conqueror (Vietnam) displaced him in 1979. These ousters tend to repeat the cycle but they are not the only options for overthrowing an inflexible regime. The cycle might be broken if the overthrow is by a democratic movement. Democratic upheavals include the US in 1776, India in 1949, and in more recent times former conquerors who had failed to acquire legitimacy were democratically deposed in Chile, and the Philippines, and temporarily in some Mediterranean Arab despotisms. . WOLT Ch 7 Exploratory examples 7-5 If someone’s distinction does not work out it may be because it is not in the WOLT domain—the domain of the rational and social— or it may be that it is just wrong. If it is wrong WOLT should enable the error to be pinpointed, as in the next example with Hirschman’s concept of “loyalty.” 3. Hirschman’s exit, voice and loyalty “Exit, voice and loyalty” were suggested in 1970 by economist AO Hirschman as three possible responses when an organisation (firm, club, government...) is in decline. His thesis generated a substantial economics and politics literature which finds exit and voice to be clear and useful. We can make them clearer and more useful by saying they are, respectively, the Type 1 response, which is to walk away and do something else, and the Type 3 response which is to criticise. Though Hirschman did not express them as dimensions and talked more in terms of actions than relations or personal dispositions, let us place his exit on the Y axis and voice on the X axis. This allocation would then have it that in times of decline the Type 2 will exercise both exit and voice. This is new and makes sense: the Type 2 administration of a firm would exit some activities (close some branches, cut some products) and work out ways to reform others. It tells us further that the 4s will do neither—neither desert nor agitate for improvement—but will be trapped, doomed to decline with the organisation unless dealt with by some 2s. Hirschman did not see the 2s but did spot the 4s; he applied the word “loyalty” to those who “suffer in silence” (Hirschman 1970: 30). The literature cannot make sense of this. “Loyalty is the most criticised concept in Hirschman’s framework…” say Dowding et al (2000: 476). It seems Hirschman is treating loyalty as an objective state. But apart from the fact that there are no objective states in social science (except thoughts themselves), circumstances are conceivable where the exercise of exit or voice would itself be loyal behaviour (i.e., the 2-ist position), and since the 4s don’t feel loyal, loyalty is not the appropriate word. A reasonable axial allocation for loyalty is listed in Table 5.4, whereby the 4s are not loyal to anyone. (If luck and fate rule, there is no point in loyalty.) Hirschman would need a word that goes onto the Z axis and contrasts with “exit” and “voice.” There does not seem to be one. We can write in “authority” WOLT Ch 7 Exploratory examples 7-6 or “coercion” (which suit the 4s suffering in silence) but they are general words and could fit in the Z column of Table 5.4 on many lines. Hirschman did realise that his “two contrasting, though not mutually exclusive, categories of exit and voice” (1970: 15) had wider application and on the first page of his 1970 book he says that his theory provided him with his “own unifying way of looking at issues as diverse as competition and the two-party system, divorce and the American character, black power and the failure of ‘unhappy’ top officials to resign over Vietnam.” Many others saw wider applications (Barry 1974: 83) and the scheme has been applied to client relations, employee attitudes, citizen satisfaction, political allegiance, even romantic alliances (Goodwin 1991, Rusbult, et al. 1986). Hirschman was not too far from developing WOLT. The main reason it did not happen would be that he and subsequent theorists considered his categories in isolation. They looked at exit, and they looked at voice. He said these were “contrasting, though not mutually exclusive” but did not follow through: if two things are not mutually exclusive then both can occur simultaneously and neither can occur. The two possibilities, both and neither, have the same validity as have either one without the other. He did see the result of “neither,” calling it misleadingly “loyalty,” but “both” seems not to have been considered at all. It also seems that no theorist systematically examines what happens when exit is selected and voice explicitly rejected—and vice versa. Having postulated exit and voice, rejection needs to be overtly considered. There is a big difference between explicitly rejecting something and just ignoring it. A theory expresses a relationship and that necessarily involves more than one object. To look at exit while merely setting voice aside, is to rely on the definition of exit and indeed the confusion in the “exit, voice and loyalty” literature is to a large extent about the meanings of terms. The fact that this literature exists, indicates that people feel there is something useful there, some hint of the way one corner of the social world works. Everything drops into place by taking the four logical possibilities for exit and voice—E not V, both E and V, V not E, neither E nor V—which not WOLT Ch 7 Exploratory examples 7-7 only sorts out organisational decline but relates it to freedom, justice, equality, identity, luck, and so on. 4. Process justice: adversarial, inquisitorial and restorative We found in Chapter 3 §3 that just process is on Y as compared with just outcome on X. However process itself can be split onto all three axes. In formal terms, the process of justice takes place in a court of law. The widely recognised processes of criminal trial—the procedure to determine culpability and to decide society’s appropriate response—are two: adversarial and inquisitorial, also known as English law and Roman law. It is not hard to see that adversarial is on Y and inquisitorial is on Z as per the third image of Table 5.1 and set out here as Table 7.2. Table 7.2. Adversarial and inquisitorial court processes, YZ Adversarial Y Yes No 1 2 3 4 No Yes Inquisitorial Z The 1s, at +Y, will be happy with adversarial competition where the two sides have equal opportunity to arrive at the truth by competitive reasoning, since 1s will be sceptical both of the accused’s claim of innocence and of the ambitious prosecutor who wants to notch up another conviction. The 1s reject inquisitorial on Z for they fear it will adjust outcomes according to status as in the Dreyfus case. The 2s, positive on all axes, do want to hear both sides and should be content with adversarial if a properly qualified judge is in charge and the process is orderly.3 The 2s also like the inquisitorial process (Z) as this delivers expert judgement and gets to the truth without disruptive argument. Truth, for 2s, is a pronouncement from an appropriately qualified and authorised official. Inquisitorial on Z also fits the 4s for whom the whole world is inquisitorial; they would reject adversarial on Y as pointless since outcomes are a matter of fate, not reasoned argument. The 3s, negative on Y and Z, want a just 3 But 2s would prefer to do away with juries, as Confucian Singapore did with its English legal heritage. WOLT Ch 7 Exploratory examples 7-8 outcome and reject both processes because adversarial is a socially divisive test of strength while inquisitorial reinforces the social dominance pattern. Besides, neither process takes the accused’s deprived childhood into account. 3-ist repentance. What is it that the 3s actually want? They seek a harmonious, egalitarian, coercion-free community so when confronted with an erring soul the 3s require repentance—a sincere confession—for readmission to the community. Adversarial and inquisitorial processes claim to be determining the truth but the truth is usually known and for 3s justice is given by harmonious resolution, not by blaming and punishing. Where the truth is unclear it will be most readily clarified if those involved can speak without fear of retribution. (Examples are Nelson Mandela’s conduct and South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission.) The 2s, who see humans as flawed but improvable, will also be pleased with confession—and glad to avoid the expense of a hearing with its potentially embarrassing revelations. This concord between the 2s and 3s suggests putting repentance onto the X axis. Does this fit the 1s and 4s who are negative on X? It does, since 1s will expect confession to be a ploy and repentance to be deceit, and 4s would confirm this by only confessing under duress or for some immediate advantage such as a reduced sentence—which is not repentance (and 3s will be disappointed when 4s re-offend). Finding the fit of English and Roman trial processes to WOLT has allowed us to see a third process of culpability, repentance, which we do not normally think of in the context of adversarial and inquisitorial. Yet it is widely used. It is applied in “restorative justice” shaming mediations between victims and offenders, a procedure available in many jurisdictions as an alternative or a preliminary to the usual court hearing, particularly for young offenders.4 3-ist confession also has the formidable heritage of the 4 http://www.criminologyresearchcouncil.gov.au/reports/strang/index.html accessed April 2012. My whole discussion is in dire contradiction to Barry Vaughan’s (2002: 420ff) discussion of Douglas’s grid-group types. Restorative justice is usually for less serious property crime but it has been used for murder. See http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/06/magazine/can-forgiveness-play-a-rolein-criminal- WOLT Ch 7 Exploratory examples 7-9 Inquisition, the Salem witch trials, and self-criticism practices under Calvin and Mao.5 It was central to the show trials in communist USSR, Czechoslovakia and Romania where regime leaders offered abject, gushing confessions of treason before being shot. An extraordinary insight into 3-ism is provided by the most prominent of the accused, Nikolai Bukharin, Politburo member, editor of Pravda and theorist of Bolshevism. In early March 1938 he and twenty others of the top Soviet leadership were tried for treason. In his final plea he reflected upon confession: For three months I refused to say anything. Then I began to testify. Why? Because while in prison I made a revaluation of my entire past. For when you ask yourself: “If you must die, what are you dying for?”—an absolutely black vacuity suddenly rises before you with startling vividness. There was nothing to die for, if one wanted to die unrepented. And, on the contrary, everything positive that glistens in the Soviet Union acquires new dimensions in a man’s mind. This in the end disarmed me completely and led me to bend my knees before the Party and the country. (USSR 1938: 777) …we repent our frightful crimes. The point, of course, is not this repentance, or my personal repentance in particular. The Court can pass its verdict without it. The confession of the accused is not essential. The confession of the accused is a medieval principle of jurisprudence. (778) The monstrousness of my crimes is immeasurable especially in the new stage of the struggle of the U.S.S.R… What matters is not the personal feelings of a repentant enemy, but justice.html?nl=todaysheadlines&emc=edit_th_20130106&_r=0&pagewanted= all which describes a case in Florida where the parents of the nineteen year-old victim forgave the murderer and which offers some reflections on the difference between Y axis anger and X axis forgiveness. 5 “Ritual self-criticism is the precondition for reintegration into the community. As Mao points out, ‘so long as a person who has made mistakes… honestly and sincerely wishes to be cured and to mend his ways, we should welcome him and cure his sickness so that he can become a good comrade’.” (Young and Ford 1977: 94, elision theirs). It is conceivable Mao was introduced to self-criticism as a youth by Protestant missionaries. WOLT Ch 7 Exploratory examples 7-10 the flourishing progress of the U.S.S.R. and its international importance. (779) WOLT tells us that confession was as essential to the USSR trials as it was to Medieval heresy trials. Communism, like Christianity, is saturation 3-ism and repentance is essential to legitimacy. Bukharin believed in the glorious new Soviet Union and that even his own death was appropriate.6 Confession and repentance restored him to the cause and community he had devoted his life to. He was executed three days later. The state needed confessions to make the treason trials of its most prominent figures legitimate and believable. The accused knew they were going to die and as 3-ist believers in socialism’s new dawn, all they had left was their membership in the community and, like confessed sinners, they went to their deaths as reconciled believers.7 Evidently, the three widely used processes of bringing wrongdoers to justice are reflections of the fundamental structure of personal and social relations. As a broader observation, the manner in which just process on Y could itself be further divided into three axes may point to a general structural feature of social relations and a way to extend and sharpen WOLT. Hood (1998: 51-70) employs this “fractal” tactic for refining the types (of grid-group theory) in the context of public management. 5. Conclusion The examples in this chapter demonstrate WOLT’s power to bring to light hidden connections. The examples are fairly specialised, pertaining to philosophy, history, economic sociology and criminal law. They show the society-wide pervasiveness of the threedimensional structure, reinforcing the finding that there are three, and only three, dimensions of values (moral preferences, policies, “relational issues”...) which logically give rise to four social 6 But see also his letter to Stalin (accessed September 2013): http://www.yale.edu/annals/Reviews/review_texts/Walden_on_Getty_Ass._New spapers_10.22.99.html 7 Compare the show trials of Germany’s Volksgerichtshof where from 1942 to 1945 Nazi court president Roland Freisler averaged three death sentences per day. Confessions were of little public interest and not voluntary. http://www.zeit.de/2005/06/A-Freisler/seite-1 accessed September 2013. WOLT Ch 7 Exploratory examples 7-11 worldviews (mindsets, ideologies, orientations...) which guide, and are guided by, four patterns of social interaction. The emphasis was on interrelationships, especially via the three dimensional structure, and in each instance the structure led to insights and information that are not possible without the theory. The next chapter is lighter, looking at poetry, song, film, fiction and proverbs and the emphasis is less on the axial interrelationships and more on the characteristics and distinctiveness of the types. 6. References to Chapter 7 Barry. 1974. “Review article ‘Exit, voice and loyalty’.” British Journal of Political Science 4(1): 79-107. Dowding, Keith, Peter John, Thanos Mergoupis, and Mark Van Vugt. 2000. “Exit, voice and loyalty: analytic and empirical developments.” European Journal of Political Research 37(4): 469–495. Goodwin, Robin. 1991. “A re-examination of Rusbult's ‘responses to dissatisfaction’ typology ”. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 8(4): 569-574. Hirschman, Albert O. 1970. Exit, voice, and loyalty: responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Hood, Christopher. 1998. The art of the state: culture rhetoric and public management. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Kant, Immanuel. 1949 [1785]. The philosophy of Kant: Immanuel Kant's moral and political writings. Edited by Carl J Friedrich. New York: Modern Library. Kissinger, Henry. 1999. Years of renewal. New York: Simon and Schuster. Olson, Mancur. 1993. “Dictatorship, democracy and development.” American Political Science Review 87(3): 567-576. Rusbult, Caryl E, Dennis J Johnson, and Gregory D Morrow. 1986. “Determinants and consequences of exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect: responses to dissatisfaction in adult romantic involvements ”. Human Relations 39(1): 45-63. USSR, People’s Commissariat of Justice. 1938. Report of court WOLT Ch 7 Exploratory examples 7-12 proceedings in the case of the anti-Soviet ‘Bloc of Rights and Trotskyites’ heard before the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the U.S.S.R. Moscow, March 2-13, 1938. Moscow. Young, LC, and SR Ford. 1977. “God is society: the religious dimension of Maoism.” Sociological Inquiry 47(2): 89-97.