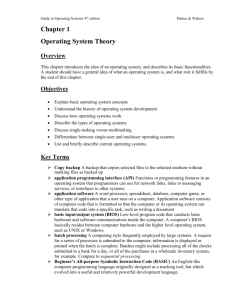

Theoretical Framework

advertisement

Predictors of Students’ Multitasking Behavior Tree Chang Southern Illinois University Carbondale USA tree@siu.edu Abstract: The multitasking phenomenon is very prevalent among students. Research on the multitasking phenomenon has either explored the extent to which it exists among students, or assessed the impact of multitasking on students’ learning activities through non-voluntary multitasking experiments. However, what causes students to multitask has not received much attention. As multitasking has become a part of students’ lives, it is important to understand the possible antecedents and the possible effects of the multitasking phenomenon on students. The purpose of this study is to investigate factors influencing students’ multitasking behavior. This is accomplished through the lens of polychronicity and behavior studies where polychronicity, sensation seeking, and technology dependence are identified as the predictors of multitasking. Introduction Multitasking is a term that refers to either doing more than one task simultaneously or doing several tasks sequentially in a specific period of time (Spink, Cole, & Waller, 2008). In the current society, it is very common to see people engage in doing several tasks at a time. For example, driving while talking on a cell phone, texting while having conversations with friends, or listening to a lecture while surfing on the Internet are illustrative of this type of behavior. Probably due to the convergence of many forms of new media and technology (de Freitas & Griffiths, 2008) as well as the increased availability of various media (Hartmann, 2009), multitasking has become the norm for most people. Previous research on multitasking focuses mainly on the following three different research questions: (1) does multitasking lead to performance decreases? (2) who has the ability to multitask? (3) who has a preference for multitasking and also believes that their preference is the best way to handle things? (König, Oberacher, & Kleinmann, 2010). Although these research streams have contributed important findings, they do not answer the question of who multitasks (König, et al., 2010). In addition, these studies focus on the environments of organizations. Although the multitasking phenomenon can be found in all generations, when compared to other generations, younger generations are more likely to multitask than older generations (Carrier, Cheever, Rosen, Benitez, & Chang, 2009). The study conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation on the youth’s media usage behavior reveals that multitasking has become a part of students’ lives; for example, about 66% of young people indicated they multitask most of the time or some of the time while using different kinds of media (Rideout, Foehr, & Roberts, 2010). Another study focusing on high school and college students’ time spent on media indicates that students multitask about 76% of their time (Jordan et al., 2005). In spite of the prevalence of multitasking among students, research on this multitasking phenomenon is just at the very early stage (Wallis, 2010). Most recent efforts are focused on field studies examining the degree to which multitasking exists among young children or youth (e.g., Rideout, et al., 2010; Roberts and Foehr, 2008). While it may be true that it is difficult for students to resist multitasking (Moeller et al., 2010), a meaningful direction to further understand the multitasking phenomenon is to explore the underlying reasons or motivations that cause students to multitask (Hartmann, 2009). In other words, what causes students to multitask? The possible antecedents or predictors of students’ multitasking behavior have not been examined. Thus, the purpose of this study is to investigate factors influencing students’ multitasking behavior. Theoretical Framework Given that multitasking habits have become a part of students’ lives, it is necessary to understand what causes students to multitask. From the viewpoint of psychology, individuals’ multitasking behaviors rely on how they allocate their attention among tasks. They may either actively or passively switch their attention from the ongoing task to other tasks. In other words, the switch of attention can be a voluntary cognitive process directed by an individual’s goals, expectations, or experiences that guide the individual to prioritize his or her cognitive resources to focus on what is important at any given time; or it can be an involuntary process caused by external stimuli that enable an individual to switch his focus from the ongoing task to another (Rizzolatti, Riggio, & Sheliga, 1994). Webster, Lichty, and Phalen’s (2006) model of media exposure provides a theoretical framework that is very similar to the viewpoint of psychology for identifying factors influencing students’ multitasking behavior. The model suggests audience factors and media factors predict audiences’ media exposure behavior. In a study of audiences’ multitasking behavior, Jeong and Fishbein (2007) state that the distinction between media and audience of the model is analogous to an individual’s innate characteristics and environmental factors on one’s multitasking behavior. Thus, Jeong and Fishbein (2007) argue that Webster, et al.’s (2006) model can be applied to understand multitasking behavior. In brief, the viewpoint of active and passive attention from psychology and Webster et al.’s (2006) distinction between media and audience suggest that individual factors and environmental factors are the two possible antecedents of multitasking behavior. Studies found some environmental conditions do affect students’ multitasking behavior, e.g., those who have a TV and a PC in their bedroom are more likely to multitask than those who do not (Foehr, 2006). As studies on the multitasking phenomena are still in the early stage (Wallis, 2010), to simplify the setting, only individual factors are discussed. In addition, individual factors are more stable than environmental factors meaning individuals’ characteristics are developed over time and they will not suddenly change their characteristics (Staw & Ross, 1985). Polychronicity Polychronicity mainly refers to the concept of doing more than one thing at a time as opposed to the concept of monochronicity, referring to the concept of performing one task at a time (König & Waller, 2010). Poposki and Oswald (2010) state that polychronicity should be a useful predictor of multitasking-related constructs due to the fact that it likely reflects the combination of an individual’s past experience with multitasking and a stable tendency to perceive multitasking as enjoyable and rewarding. König and Waller (2010) made a clear distinction between multitasking and polychronicity. They suggest that polychronicity is an individual’s attitude for doing several things at the same time, whereas multitasking is the behavioral aspect of polychronicity. Attitude can be conceived as an evaluating judgment in the sense of liking or disliking an object (Scherer, 2005). König, et al. (2010) argue that individuals’ values are congruent with their behavior. That is, people who have high polychronicity values are also the ones who multitask. The theory of planned behavior (TPB) also provides support to the relationship between polychronicity (an individual’s attitude) and multitasking (the actual behavior). According to TPB, an individual’s attitude about the behavior is one of the antecedents of an individual’s behavioral intention and the behavioral intention in turn predicts the actual behavior. TPB has been empirically tested by many researchers, and it exhibits considerable predictive power for behavioral intention (Mathieson, 1991), suggesting that an individual’s attitude is related to his behavior toward a specific object. Based on the viewpoint of polychronic studies as well as TPB, this paper expects polychronic individuals to be more likely to engage in multitasking tasks. Thus, this paper proposes: Proposition 1: There is a positive relationship between polychronicity and students’ multitasking behavior. Sensation Seeking The term sensation seeking refers to individuals’ need to seek stimulation. Sensation seeking individuals are more likely to engage in behaviors that increase the amount of stimulation they experience. Because the process of multitasking involves heightened sensation, it makes sense that sensation seeking youth are more likely to multitask (Kirsh, 2010). A literature review that abstracted students’ descriptions about why they multitask reveals that they consider multitasking behavior as exciting, cool, and providing immediate gratification (Lenhart, Rainie, & Lewis, 2001; Rideout, et al., 2010; Wallis, 2006). This implies that sensation seeking is a potential predictor of multitasking. From a theoretical perspective, how sensation seeking relates to multitasking behaviors may be explained in terms of uses and gratifications theory. This theory suggests that social and psychological needs lead people to use the media to fulfill specific gratification (Katz, Blumler, & Gurevitch, 1974). According to Zuckerman’s (1979) definition of sensation seeking, high sensation seekers have a stronger need for varied, novel, and complex experiences and, therefore, are more likely to engage in certain types of activities that can fulfill their gratification. Without a high level of stimulation, sensation seekers get bored easily. Therefore, sensation seekers need to keep pursuing stimuli to satisfy themselves. Based on the literature review of reasons that students multitask and the gratification theory, it is expected that sensation seeking will be related to multitasking behavior. Specifically, those who have a stronger need for varied, novel, and complex experiences are more likely to seek other activities while attending to one or more tasks. Thus, this paper proposes: Proposition 2: There is a positive relationship between sensation seeking and students’ multitasking behavior. Technology Dependence Modern information technology such as computers, cell phones, iPods, and other portable computing devices was once single-purpose oriented. But now, due to technology convergence (de Freitas & Griffiths, 2008), most modern information technology has evolved into general-purpose oriented devices that allow users to perform a variety of tasks, sometimes simultaneously. For instance, a smartphone is a portable computer that allows users not only to make and receive phone calls but also to access different kinds of Internet services. With such features embedded in these technological devices, one would argue that information technology acts as the catalyst of the multitasking phenomenon. Studies have shown that the use of some information technology is associated with multitasking behavior. For instance, Garrett and Daziger (2008) found heavy users of instant messaging (IM) were more likely to multitask than light users of IM; the findings of Zhong, Hardin, and Sun (2011) show that those who spent more time on social networking sites such as Facebook were more likely to be multitaskers. Studies have also shown that students highly rely on different kinds of digital media. A study conducted by the International Center for Media & the Public Agenda (ICMPA) at the University of Maryland asked 200 college students to stop using all kinds of media for 24 hours and then students were asked to write about the experience (Moeller, et al., 2010). Students negatively reacted to the media-free event, stating that it made them feel withdrawal and anxiety. Moreller, et al. (2010) concluded that most college students are not just unwilling, but functionally unable to be without their media connections to the world, which suggests that students are highly dependent on information technology. The media dependency theory developed by Ball-Rokeach and DeFleur (1976) may provide a theoretical viewpoint on the relationship between technology dependence and multitasking behavior. The media dependency theory states that the more an individual becomes dependent on the media to fulfill his or her needs, the more important the media will be to the individual. In addition, while an individual is dependent on the media, the media will have much more impact and power over the individual. It has been demonstrated that students are heavily dependent on technology (Moeller, et al., 2010), suggesting that students perceive that the technology they choose is meeting their needs and impacting their behavior. Since the technology is multitasking oriented, the multitasking nature of technology not only fulfills students’ needs, but also fosters students’ multitasking behaviors. Thus, this paper anticipates that those who are dependent on technology will be more likely involved in multitasking behavior. Proposition 3: There is a positive relationship between technology dependence and students’ multitasking behavior. Contribution The theories and literature used to support the propositions represent the first attempt to add to the body of knowledge on students’ multitasking behavior. Multitasking has become a very common phenomenon among students but why they multitask is still unclear. This paper argues that polychronicity, sensation seeking and technology dependence are likely to predict students’ multitasking behavior. Without empirical data, this paper is unable to conclude the plausibility of the three propositions. However they may provide a way for educators to have a better understanding of students’ multitasking traits and hopefully this understanding can lead educators to create a learning environment or teaching strategies that are best for these multitaskers. Future Research Opportunities This paper provides several research opportunities for adding knowledge to multitasking studies. First, empirical data is required to assess whether the three factors predict students’ multitasking behavior. We are currently conducting an online survey to assess the plausibility of the propositions. If the propositions are supported, it will extend the scope of TPB, the media dependency theory, and the uses and gratifications theory from other disciplines to educational environments as well as answer the question of who multitasks. Second, there are many technologies that can be a source of multitasking behaviors such as smart phones, computers, and mobile devices. Especially, computers and cell phones are very popular among students (Kvavik, 2005). It will be interesting to examine the impacts of different technologies on students’ multitasking behavior. Third, this paper does not consider environmental factors. As a result, future study can extend the view of this paper by adding environmental factors such as ownership of technology explaining students’ multitasking behavior . Conclusion Most current students grow up with technology, or they never experience life without technology. As multitasking has become the norm for students, understanding what causes them to multitask is important for researchers to further understand the multitasking phenomenon. This paper is the first step in understanding some of the individual factors on students’ multitasking behavior References Ball-Rokeach, S. J., & DeFleur, M. L. (1976). A dependency model of mass-media effects. Communication Research, 3(1), 3-21. Carrier, L., Cheever, N., Rosen, L., Benitez, S., & Chang, J. (2009). Multitasking across generations: Multitasking choices and difficulty ratings in three generations of Americans. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(2), 483-489. de Freitas, S., & Griffiths, M. (2008). The convergence of gaming practices with other media forms: what potential for learning? A review of the literature. Learning, Media and Technology, 33(1), 11-20. Foehr, U. G. (2006). Media multitasking among American youth: Prevalence, predictors and pairings: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Garrett, R. K., & Danziger, J. N. (2008). IM= Interruption management? Instant messaging and disruption in the workplace. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 13(1), 23-42. Hartmann, T. (2009). Media choice: a theoretical and empirical overview. New York, NY: Routledge. Jeong, S. H., & Fishbein, M. (2007). Predictors of multitasking with media: Media factors and audience factors. Media Psychology, 10(3), 364-384. Jordan, A., Fishbein, M., Zhang, W., Jeong, S., Hennessy, M., Martin, S., et al. (2005). Multiple media use and multitasking with media among high school and college students. Paper presented at the the annual International Communication Association Conference, New York. Katz, E., Blumler, J., & Gurevitch, M. (1974). Utilization of mass communication by the individual. The uses of communications: Current perspectives on gratifications research, Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 19-32. Kirsh, S. J. (2010). Media and youth: a developmental perspective: Wiley-Blackwell. König, C. J., Oberacher, L., & Kleinmann, M. (2010). Personal and situational determinants of multitasking at work. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 9(2), 99-103. König, C. J., & Waller, M. J. (2010). Time for reflection: A critical examination of polychronicity. Human Performance, 23(2), 173-190. Kvavik, R. B. (2005). Convenience, communications, and control: How students use technology. Educating the net generation, 7.1-7.20. Lenhart, A., Rainie, L., & Lewis, O. (2001). Teenage Life Online: The rise of the instant-message generation and the Internet's impact on friendships and family relationships: Pew Internet & American Life Project Washington, DC. Mathieson, K. (1991). Predicting user intentions: comparing the technology acceptance model with the theory of planned behavior. Information systems research, 2(3), 173-191. Moeller, S., Chong, E., Golitsinski, S., Guo, J., McCaffrey, R., Nynka, A., et al. (2010). A day without media. Retrieved May 23, 2010, from http://withoutmedia.wordpress.com/ Poposki, E. M., & Oswald, F. L. (2010). The multitasking preference inventory: toward an improved measure of individual differences in polychronicity. Human Performance, 23(3), 247-264. Rideout, V. J., Foehr, U. G., & Roberts, D. F. (2010). Generation M2: media in the lives of 8-to 18-year-olds: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Washington, DC. Rizzolatti, G., Riggio, L., & Sheliga, B. M. (1994). Space and selective attention. In C. Umilta & M. Moscovltch (Eds.), Attention and performance XV: MIT Press. Scherer, K. R. (2005). What are emotions? And how can they be measured. Social Science Information, 44(4), 695729. Spink, A., Cole, C., & Waller, M. (2008). Multitasking behavior. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 42(1), 93-118. Staw, B. M., & Ross, J. (1985). Stability in the midst of change: A dispositional approach to job attitudes. Journal of applied psychology, 70(3), 469-480. Wallis, C. (2006). The multitasking generation. Time Magazine, 167(13), 48-56. Wallis, C. (2010). The impacts of media multitasking on children's learning and development: Report from a research seminar. New York, NY: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop. Webster, J. G., Lichty, L. W., & Phalen, P. F. (2006). Ratings analysis: the theory and practice of audience research (3rd ed.). Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Zhang, W. (2011). Multitasking with new media in large classrooms: Findings from online survey and focus groups. In S. D. Liew (Ed.), Technology in Higher Education: The State of the Art. Singapore: Center for Development of Teaching and Learning, National University of Singapore. Zuckerman, M. (1979). Sensation seeking: Beyond the optimal level of arousal. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawerence Erlbaum.