Mental Health and Addiction Credential in

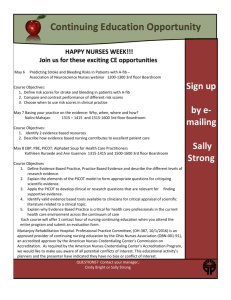

advertisement