Ethics and the Human Good Research Paper

advertisement

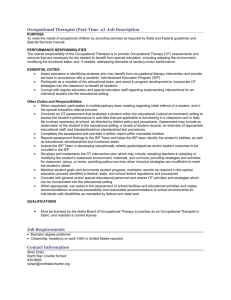

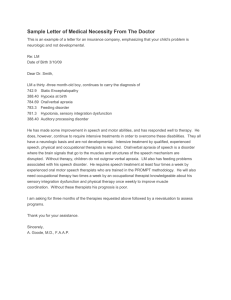

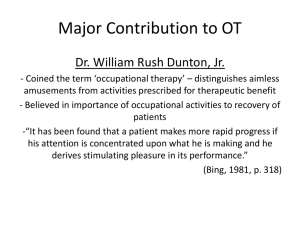

Kaitlyn Powell Dr. Rosato VTTH 300 D: Ethics and the Human Good 21 April 2015 Ethical Dilemmas in the Discharge of Patients from Hospitals: An Occupational Therapist Perspective An occupational therapist’s main priority is their client. However, is there a point where the therapist must put their needs before their clients? If so, where does that point lie, and is it ethical for the therapist to do so? One such situation where these questions arise is during the process of discharging patients from hospitals. Occupational therapists provide dignified and ethical care for their patients; however, due to outside pressure from clients, other professionals, and hospitals during the discharge of patients from hospitals, therapists must choose to either abandon their morals and therefore sacrifice the internal goods of their practice in order to satisfy the needs and wants of their higher-ups, or maintain their morals and risk their jobs to insure the safety and success of their clients. Occupational therapists are responsible for helping individuals to develop or restore skills that are useful in every day life. They take the “occupational” approach, which means the therapy consists of the activities the patient wants to learn (“Occupational Therapy”). For example, therapists will help young children learn to write or tie their shoes, or they will help stroke victims relearn how to use a fork to eat dinner by using these tasks as their therapy. Often times the therapist will provide modified utensils or settings to allow their client to perform these tasks on their own (“Occupational Therapy”). Occupational therapists work with a variety of patients such as children, rehabbing clients, stroke victims, and the elderly. Because of the Powell 2 variety of patients they work in many settings such as schools, nursing homes, private practices and hospitals. Aside from the physical benefits that OTs provide for their clients, therapists also help to restore and maintain the dignity of their patients by preserving their ability to do basic human activities on their own (“Occupational Therapy”). Occupational therapists hold themselves to a high standard of ethics. Their Ethical Code is laid out by the American Occupational Therapy Association, which names seven core values of an occupational therapist. The Code addresses the concerns of the stakeholders in Occupational Therapy, which include the practitioners, clients, researchers, educators, students, as well as others (Reed, 1). The core values apply to all of the stakeholders listed, and they are: altruism, equality, freedom, justice, dignity, truth, and prudence (Reed, 1). Each of these values is defined in terms of the relationship between therapist and client. Altruism refers to the therapist’s ability to place the patient’s needs above his or her own. Equality has to do with the therapist treating patients and fellow practitioners with fairness, and freedom is the idea that the client’s desires must guide the therapist’s intervention. Similar to freedom is justice, which is the formation of fair and impartial relationships between clients and therapists, as well as adhering to their area of practice’s laws and standards. Dignity is about the promotion of the patient’s individuality by helping the client to become independent in activities that are meaningful to them, regardless of their disability level (Reed, 2). Truth and prudence have to do with providing accurate information, as well as using their “clinical and ethical reasoning skills, sound judgment, and reflection to make decisions to direct them in their areas of practice” (Reed, 2). The Occupational Therapy Code of Ethics and Ethics Standards also outlines seven principles of Occupational Therapy that are reflective of the seven virtues. The seven virtues are beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy and confidentiality, social justice, procedural justice, Powell 3 veracity and fidelity. Beneficence and non-maleficence is the concept that therapists will do all they can to help their client, and have an obligation to not intentionally harm them (Reed, 3-4). Occupational Therapists, as professionals, have autonomy over their profession to treat their patients as they wish as long as it is within the bounds of the standards, and they also have the right to maintain confidentiality with their clients regarding treatment options and other decisions. Social and procedural justice both have to do with equal use of resources and equal treatment for all clients, and veracity is about the accurate transfer of information and ensuring the client’s understanding (Reed, 6-8). Finally, fidelity is the idea that therapists must keep their promises and commitments to their clients (Reed, 9). All of the principles and virtues of occupational therapy are threatened when an OT must question their morals. Because of the inconsistencies in their work, therapists will make decisions on a case-by-case basis, and overarching principles wont always apply in a black-and-white fashion. The fourteen virtues and principles of occupational therapy are the internal goods of the practice, all of which must be applied in order to reach the end of the institution. Internal goods are defined as those qualities and abilities that come from working towards excellence in that practice (MacIntyre, 175). For example, prudence is one of the virtues of occupational therapy, and it is one that comes from striving to be a good therapist. Similarly, altruism is a virtue as well, one that might come naturally to some but that is sincerely developed over years of assisting others on their journey to autonomy. Because occupational therapy is also an institution, it necessarily has an end. The end of an institution is what that thing is when it is in its’ very best state. The end of occupational therapy as an institution is bettering the lives of clients who seek out therapy, as well as restoring the dignity to those patients. A therapist who is achieving the end of OT is one who does this for his or her clients. As discussed, one who Powell 4 achieves the end of one’s institution will also benefit from the development of the internal goods, in this case the fourteen virtues and principles of occupational therapy. In the field, oftentimes the temptation of external goods of occupational therapy will draw a therapist away from achieving the end of the institution. For example, a high pay scale, prestigious status, the impressiveness of the degree, and things of this nature will bring individuals into the field for the wrong reasons, and these people will not pursue the end of the institution, but will pursue their own purpose. A purpose differs from an end in that an end belongs to the thing itself, while the purpose is a human intention imposed on a thing (Sokolowski, 509). These therapists with their own purposes for the field, when tested morally, will be more willing to fold than those pursuing the ends of the institution because they lack the sincere desire to better their institution. There are two possibilities when a supposed ethical dilemma arises, which is why the evaluation of these ethical dilemmas must be evaluated. Either there is a sincere dilemma where there is no right or wrong option, in which a therapist must apply their skills and virtues as best they can to ensure the most ethical solution, or the therapist has their own intentions which leads them to choose the solution that best fits their needs. One such situation where the morality of the therapist and the ethical dilemmas collide is during the process of discharging patients from hospitals. Discharge planning is defined as “the primary means to ensure that patients needs will be met in the post discharge environment” (Atwal & Cadwell, 244). The process of discharging a patient from the hospital first involves home visits from the therapist to assess the safety of the home and potential modifications to the living space (Drummond, 389). These home visits also included primary caretakers for the victims, where the therapist could teach them how to effectively perform transports and activities of daily living, as well as work with necessary equipment provided for those activities Powell 5 (Drummond, 389). After the home visits, occupational therapists will have meetings with other professionals of different disciplines. (Atwal & Caldwell, 244). From there, decisions on the patient’s future will be solidified—these are the areas where ethical dilemmas will arise. The four main virtues of Occupational therapists that are threatened during the process of discharge planning are autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice (Atwal & Caldwell, 248-249). During the home visits, occupational therapists will be faced with clients and care takers whose main concern is getting their loved one’s home. The therapist’s main concern is getting the client healthy, and these two goals are not always identical—a therapist might encounter homes that are unlivable for their client, such as a high level apartment with no elevators for a client with trouble walking. In these situations a therapist has to choose their patient’s autonomy or their own beneficence. Oftentimes an individual’s desires and what is best for them do not line up exactly, putting the therapist in the position of accepting an inferior outcome than they have planned for their clients. During the process of patient discharge, occupational therapists are recognized along with physiotherapy and speech and language therapy practitioners face the most ethical dilemmas (Atwal & Caldwell, 244). Some of these issues arise because successful patient discharge is dependent on the collaboration of interdisciplinary professionals. Each of these professionals will have completed their own level of graduate education and will have their own code of ethics that they have to uphold. While generally all of these professionals will have the success of the discharge as their main goal, they will have different ways of going about that as well as different ideas on which solutions are moral and which solutions are not (Atwal & Caldwell, 244). Another problem is with the availability of resources for patients. Misdistribution leads to a lack of availability, putting therapists in the position of having to choose who receives what Powell 6 they need, and who has to go without. This greatly threatens the virtues of equality justice—how does one decide who goes with and who goes without while still upholding the fair treatment of all clients? Does the person with the worst condition get the better treatment, or does the person with the best prognosis? Either way, someone will have to be excluded, and could be missing out on necessary treatments that would allow them to be discharged. And, in the case of those who don’t receive the treatment, is it safe to discharge them without it, and better yet, is it ethical? In such a situation the therapist would have to decide which of their virtues they hold higher—the dignity of their patients by allowing them to go home and not live in a hospital, or their nonmaleficence, which prevents them from doing that which they believe could harm their patient? In either situation their moral code is being broken; however it is a decision that cannot be avoided, as its effects will be played out on human lives. Another area of contention is in the discussion of autonomy. Therapists, as professionals, have the autonomy to decide what treatment paths to follow, and if and when to abandon them. However, clients also have a certain level of autonomy when it comes to their treatment. Therefore, the client can make decisions regarding his or her treatment that the therapist has not been consulted on -and therefore might not agree with- but have to follow regardless (Atwal & Caldwell, 248). A classic example of this is when a patient has decided that they want to go home, and have set up their date to leave without consulting their therapist, who might not believe their patient to be ready for discharge. Does the occupational therapist uphold their patient’s autonomy by allowing them to leave, or do they prevent their patient from leaving in the name of beneficence and non-maleficence? It always boils down to which virtue trumps which virtue, and who actually knows best, client or therapist? Powell 7 Beneficence raises some ethical dilemmas of its own when it comes to discharging patients. Beneficence is the concept that occupational therapy practitioners must only do good for their patients, and do everything they can to benefit their patients within occupational therapy standards (Reed, 3). However, some therapists might be restricted by education levels or certifications, which prevent them from prescribing certain equipment. Atwal and Caldwell describe a situation where a therapist prescribed a hoist for a patient despite not having the proper authorization to do so (248). In this case, the hoist took two extra weeks to arrive and did not fit under the bed properly. The patient’s discharge was unnecessarily pushed back by three weeks. The therapist faced an ethical dilemma—should she go beyond her authorization to provide what she thought necessary, or should she potentially ignore the principle of nonmaleficence by allowing her patient to be discharged without this equipment she believed to be essential? In this case her solution ended up being the less ethical decision of the two, but as the therapist who prescribed the hoist said, “it really is quite stressful” (Atwal & Caldwell 248). Non-maleficence and beneficence often get lumped together; however, there is a difference between the two. While beneficence is an obligation for the therapist to do good things for their clients, non-maleficence prevents an occupational therapist from knowingly allowing harm to come to their patient, whether through ignorance or through being witness to mistreatment of or misbehavior by the client. Also under non-maleficence, therapists have an obligation to act on behalf of their clients when they are impaired or otherwise unable to speak for themselves in order to preserve their autonomy. However, advocating for patient’s rights can sometimes go against what even the therapist thinks best. For example, a client might feel that a certain treatment is doing more harm than good and decide they no longer want to receive it. Even if the therapist feels that the treatment is necessary to get the patient to a state where they Powell 8 are allowed to be discharged, their code of ethics obliges them to advocate for the patient’s autonomy (Atwal & Caldwell, 248-249). This makes occupational therapists rather unpopular at times. Doctors, neurologists and physical therapists don’t want to hear another professional telling them what they should and shouldn’t do for their patient, especially when they know that what they are doing is working. So, the temptation is to attempt to convince the patient that the doctors know best, or even ignore the complaints to avoid the backlash of their peers. In this case, it is evident that the ethical solution is to protect the autonomy of the client; however, occupational therapists will face blame for slowing the discharge process, which can cloud their judgment. A final fundamental virtue of occupational therapy is justice, which boils down to respecting the rights of each individual that one encounters, including practitioners, peers, clients, and their caretakers. The occupational therapist’s ability to preserve this respect is threatened by the hospitals they work in. Therapists are under pressure to move patients and clear beds in order for more patients to enter. This leads to therapists cutting corners to clear beds, which absolutely breeches the code of ethics, and is also disrespectful to the client. However, this dilemma is caused by outside pressure from the medical institution and all the blame cannot be placed on the occupational therapist—the high expenses and high profit oriented medical institutions place unnecessary pressure on their employees which forces them to question their morals in order to keep their jobs. Occupational therapy is a practice whose internal goods are under attack. The end of occupational therapy as an institution is not being achieved because the morals that comprise the internal goods are threatened by ethical dilemmas, especially during the process of discharging patients from hospitals. The virtues of Occupational therapists that are most susceptible to ethical Powell 9 corruption are autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice. Occupational therapists aim to provide dignified and ethical care for their patients; however, due to outside pressure from clients, other professionals and hospitals during the discharge of patients from hospitals, therapists must stare ethical dilemmas in their faces and determine which of their virtues they have to abandon. Powell 10 Bibliography Atwal, Anita, and Kay Caldwell. "Feature Article Ethics, Occupational Therapy And Discharge Planning: Four Broken Principles." Australian Occupational Therapy Journal 50.4 Drummond, Aer, et al. "Occupational Therapy Predischarge Home Visits For Patients With A Stroke (HOVIS): Results Of A Feasibility Randomized Controlled Trial." Clinical Rehabilitation 27.5 (2013): 387-397. SPORTDiscus with Full Text. Web. 22 Mar. 2015. MacIntyre, Alasdair C. After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory. 2nd ed. Notre Dame, Ind.: U of Notre Dame, 1984. Print. “Occupational Therapy: Improving Function While Controlling Costs.” AOTA. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 1 Nov. 2010. Web. 22 Mar. 2015. <http://www.aota.org/About-Occupational-Therapy/Professionals.aspx>. Reed, Kathlyn, Barbara Hemphill, Ann Moodey Ashe, Lea Brandt, Joanne Estes, Donna Homenko, Craig Jackson, Debora Slater, and Loretta Foster. "Ethics." - AOTA. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 1 Nov. 2010. Web. 22 Mar. 2015. <http://www.aota.org/Practice/Ethics.aspx>. Sokolowski, Robert (2004). What is Natural Law? The Thomist 68 (4):529.