PH-2 Indicators of Waterborne Pathogens_ DRAFT with TAC

advertisement

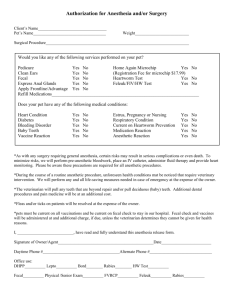

‘’ PH-2: Continue Source and Risk Assessments of Human and Environmental Health Indicators Suitable for Tampa Bay Beaches and Other Recreational Waters OBJECTIVES: Support and monitor research into microbial indicators of waterborne pathogens harmful to human and environmental health. Support and monitor advancements in analytical techniques to directly detect, identify and track waterborne microbial pathogens. Support adoption of best available detection, identification and source tracking methodologies. Increase public education and awareness about waterborne fecal pathogens, beach advisories, and best practices to reduce public exposure. STATUS: Ongoing. Action revised from Continue source and risk assessments of human and ecosystem health indicators suitable for subtropical marine beaches and waters. BACKGROUND: Tampa Bay area beaches and recreational waters are nationally recognized for their outstanding natural beauty. They provide recreational opportunities to residents and visitors alike, and support Tampa Bay’s diverse economy, especially its recreation and tourism industries. Maintaining suitable water quality at beaches and other recreational waters is foundational to protecting Tampa Bay’s environment and economy. Early detection of waterborne microbial pathogens (pathogenic microbes) is critical to public health, and to public confidence in monitoring and risk assessments of health threats. Bacteria, viruses and protozoa can cause a variety of human illnesses ranging in severity from rashes, ear, nose and throat infections, and diarrhea to more life-threatening illnesses including antibioticresistant infections, cholera and typhoid fever. Some naturally occurring bacteria (e.g. Vibrio vulnificus) may also pose human health concerns for those who consume raw seafood or have depressed immune systems. Increasing water temperatures in the Bay may enhance susceptibility to these bacterial infections, and facilitate the introduction of potential new pathogens from tropical environments. Fecal coliform bacteria, especially Escherichia coli (E. coli) are widely used as indicators for waterborne pathogens. Coliform bacteria occur naturally in animal feces, and when detected in high concentrations may indicate the presence of co-occurring harmful pathogens. However, because they are present in the feces of a wide variety of animals, they do not pinpoint human sources of contamination. Moreover, Florida’s subtropical climate allows fecal coliforms to grow and multiply naturally in the environment. These shortcomings can reduce the consistent predictive value of coliform bacteria as an indicator of more harmful pathogens and their threats to human health. 1 ‘’ A study of alternative, more accurate indicators of pathogens sponsored by TBEP and Pinellas County identified enterococci bacteria (Enteroccocus species) as the best fecal indicator bacteria for subtropical marine waters because they have a greater correlation with water-related gastrointestinal illness in both marine and freshwater than other fecal indicator bacteria and can survive longer in saltwater (Rose et al. 1999). However, because enterrococci bacteria are shed in feces of all warm-blooded animals, they cannot be used to pinpoint human contamination sources. The study ultimately recommended the use of enterococci, along with fecal coliform bacteria, while proposing source tracking of the fecal coliform to fingerprint the types of bacteria found to human sources. In 2000, as part of the Healthy Beaches Program, Tampa Bay Area county health departments began collecting bi-weekly (weekly since 2002) water samples at area beaches and analyzed them for enterococci and fecal coliform bacteria (Table 1). City and county water quality agencies assist in collecting these samples. In general, water quality in the Tampa Bay area ranges from excellent at Gulf beaches to moderate at bay and inland waterway beaches to poor at lakes and other freshwater environments. Area health departments issue advisories or warnings when conditions warrant, although a consistent link between exposure to these indicator organisms and public health risk still remains unclear. In 2012, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released new recreational water quality criteria (RWQC) recommendations for protecting human health in all waters designated for primary contact recreation use (EPA 2012). The new RWQC included two sets of numeric concentration thresholds for enterococci bacteria (marine and freshwater) and E. coli (freshwater). In addition, EPA provided new Beach Action Values (BAVs) for states to consider using as a more conservative, early alert to beachgoers. In 2015, Florida DEP proposed new criteria for surface waters, including replacing criteria for fecal coliform with E. coli (freshwater) and enterococci (marine water). Although great gains in protecting public health have been made using fecal indicator bacteria, viral pathogens may cause a significant portion of waterborne illness. Because viruses and bacteria respond differently to water treatment processes and environmental degradation, traditional fecal indicator bacteria may not be good indicators for their presence. Research into bacteriophages, or viruses that infect and replicate within bacteria, hold promise for developing better indicators of viral pathogens. EPA (2015) suggested that coliphages (viruses that infect and replicate within E.coli) may be better indicators of viruses in fecal contamination than current bacterial indicators and may yield more accurate methodologies for evaluating water quality and protecting public health. Advances in direct pathogen identification methodologies coupled with microbial source tracking may soon revolutionize water quality analysis. Locally, EPC is funding a microbial source tracking study of fecal contamination in the Bullfrog Creek/Sweetwater Creek watersheds; results will help pinpoint specific sources and inform reduction or prevention strategies. New methodologies can now detect and identify the genetic material from multiple pathogens in water samples (Li et al. 2015). This direct, multi-target approach has the added benefit of eliminating false negatives (i.e., determining waters are safe, when they may not be) 2 ‘’ from measuring the wrong indicator or pathogen. Finally, advances in quantitative PCR (qPCR) as a rapid test for fecal contaminants enable same-day results, providing more timely information to beach-goers and the ability to target caution advisories to target audiences, such as those with compromised immune systems. STRATEGY: ACTIVITY 1 Continue to support and monitor research into sources and risks associated with indicators of waterborne fecal pathogens harmful to human and environmental health. Support and monitor research into new analytical techniques to directly detect and identify microbial pathogens. Investigate fecal indicators that more accurately indicate presence of waterborne pathogens harmful to human and environmental health. Investigate fecal indicators that provide information about contamination sources, i.e. methods that can discriminate between contamination from sewage vs. animals (microbial source tracking). Explore the use of quantitative PCR (qPCR) as a same-day notification to better protect public health. Evaluate the use of multi-target methods for detecting fecal indicators and pathogens, e.g. DNA sequencing and microarray. Evaluate coliphages as indicators of viral pathogens associated with fecal pollution. Better establish the link between exposure to certain pathogens and risk of disease – with special emphasis on at-risk populations (elderly, immuno-compromised). Identify sources of fecal indicators (animal type, septic tank, boating, natural vegetation and sediments). Determine fate of fecal indicators and pathogens, i.e., how long an organism persists before the risk becomes negligible. Predict weather and water conditions that will intensify or diminish the contamination. Evaluate the need to add additional areas to recreational beaches currently monitored. Identify best practices to remediate fecal contamination. Responsible Parties: USF Healthy Beaches/Healthy Coasts; Florida Healthy Beaches Program (Florida Department of Health); Pinellas, Hillsborough and Manatee County health departments; FDEP; US EPA, TBEP. Timeframe: Initiate in 2020, pending availability of funds Cost and Potential Funding Sources: $$ Federal funding agencies, including NIH, EPA, NSF Location: Research conducted in Tampa Bay Area waters Benefit/Performance Measure: Better understanding of sources and risks associated with fecal indicator bacteria and associated pathogens. 3 ‘’ Results: Improved detection of pathogens in recreational waters; improved public safety; improved monitoring of stormwater and wastewater management in Tampa Bay watersheds. Deliverables: Research and technical reports with recommendations for best indicators, relative risk by pathogen, and tools for identifying sources of fecal indicator bacteria and pathogens ACTIVITY 2 Encourage adoption of best available detection, identification, source tracking and remediation techniques at state and national level. Locally, encourage use of DEP guidance documents for bacteria contaminational that present low-tech, operational practices (such as removing sediments in stormwater systems) that may substantially reduce bacteria loadings in wastewater and stormwater systems. Responsible Parties: USF Healthy Beaches/Healthy Coasts; Florida Healthy Beaches Program (Florida Department of Health), Pinellas, Hillsborough and Manatee County health departments, FDEP, US EPA, TBEP. Timeframe: Initiate in 2017 Cost and Potential Funding Sources: $-$$ Location: N/A Benefit/Performance Measure: Improved detection, identification and source tracking of pathogens in recreational waters; improved public safety; Results: Improved water quality analysis, better understanding of fecal contamination sources, more relevant public notification and protection for public health. Deliverable: Recommendations for best available water quality analysis methodologies. ACTIVITY 3 Enhance public education and awareness about waterborne fecal pathogens, beach advisories, and best practices to reduce public exposure. Post beach advisories and Healthy Beaches reports for Hillsborough, Pinellas and Manatee Counties on Tampa Bay Water Atlas Update the “Is It Safe To Swim In The Bay?” fact sheet to include precautions against swimming in stormwater ponds and residential canals Utilize rapid testing methods to provide same-day notification of contaminated water bodies. Responsible Parties: Florida Healthy Beaches Program, TBEP, Tampa Bay Water Atlas Timeframe: Ongoing Cost and Potential Funding Sources: $ Location: Tampa Bay Area Benefit/Performance Measure: Better communication and coordination of public health notices/warnings Results: Improved public knowledge and safety Deliverable: Outreach on waterborne fecal pathogens, beach advisories and best practices to reduce public exposure; a local up-to-date, database of advisories 4 ‘’ References EPA 2014. Microbiological risk assessment (MRA) tools, methods, and approaches for water media. US EPA Office of Science and Technology, Office of Water. EPA-820-R-14-009. 146pp. EPA 2015. Review of coliphages as possible indicators of fecal contamination for ambient water quality.US EPA Office of Science and Technology, Office of Water. EPA-820-R-15-098. 119pp. Li X, V.J. Harwood, B. Nayak, C. Staley, M.J. Sadowsky and J. Weidhaas. 2015. A novel microbial source tracking microarray for pathogen detection and fecal source identification in environmental systems. Environ Sci Technol 49(12):7319-29. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b00980. Rose, J.B., J.H. Paul, M.R. McLaughlin, V.J. Harwood, S. Farrah, M. Tamplin, G. Lukaski, M.D. Flanery, P. Stanek, H. Greening and M. Hammond. 1999. Healthy Beaches Tampa Bay: Microbiological monitoring of water quality conditions and public health impacts. 204pp. Figures and Tables Table 1: Beaches monitored for water quality in the Tampa Bay Area Hillsborough County Beaches Pinellas County Beaches Manatee County Beaches Bahia Beach Ben T. Davis North Ben T. Davis South Cypress Point Park North Cypress Point Park South Davis Island Beach Picnic Island North Picnic Island South Simmons Park Beach Courtney Campbell Causeway Fort DeSoto North Beach Honeymoon Island Beach Indian Rocks Beach Madeira Beach Pass-a-grille Beach Redington Shores – 182nd Ave Sand Key Sunset Beach, Tarpon Springs Treasure Island Beach Bayfront Park North Bradenton Beach Broadway Beach Access (FKA Whitney Beach) Coquina Beach North Coquina Beach South Manatee Public Beach North Palma Sola South 5