Women in Egypt

advertisement

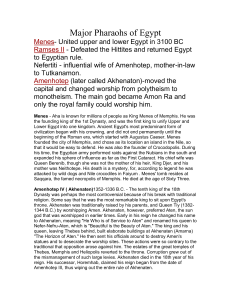

Women in Egypt The high level of respect for women made Egyptian society unusual for its time. Women in the royal household could become especially influential. Egyptian society was used to women ruling as co-regents until their sons came of age. Ahhotep ruled Egypt during its darkest days while she waited for her son, Ahmose, to reach adulthood. More unusually, the female pharaoh, Hatshepsut successfully ruled for some 20 years. First among equals Unlike other Egyptians, pharaohs were polygamous - they had more than one wife, but just one principal queen. She was the wife whose male children were acknowledged as the pharaoh's heirs. Although Egyptian queens previously enjoyed very little power, the situation changed dramatically during the New Kingdom period. Instead of just bearing children, the principal queen became an essential part of her husband's reign. Any attempt to rule without a consort became an offence against Maat, the divine order of the universe. Wifely duties Like any dutiful wife, an Egyptian queen was expected to support her husband. She had a variety of religious and political duties that reinforced the position of the royal family. For example, Queen Tiy, wife to Amenhotep III, may have been born a commoner but was soon corresponding with foreign princes as an equal. Similarly, Queen Nefertiti was a full participant in religious ceremonies honoring Aten, the sun god. Independent woman Queens were also given estates, which provided them with financial independence. This enabled them to commission their own monuments and even develop their own religious symbols. These were designed to remind the people that their queen was close to being a god: a crown of tall feathers, for example, indicated links with the gods Min, Amen and Re. Some pharaohs made the link more obvious. Amenhotep III and Ramesses the Great each built temples for their principal queens, Tiy and Nefertari. The temples were dedicated to them, so the two pharaohs and their consorts were worshipped as gods - a lasting tribute to loving partners. Nefrititi The most powerful woman in Egypt since the Pharaoh Hatshepsut 100 years earlier, Queen Nefertiti was as influential as she was beautiful, a partner in power with her king, Akenhaten. Although Nefertiti was not born of royal blood, she had grown up close to the royal family. Some evidence suggests that her father was the powerful courtier Ay, advisor to three pharaohs, including Akenhaten, Nefertiti's husband. Like him, Nefertiti would prove to be a key player at court. Hell hath no fury... During her marriage to Akenhaten, Queen Nefertiti stood with him at the head of the new regime. Carved images on ancient temples show her killing Egypt's enemies - previously only a role given to the pharaoh. When Akenhaten moved the government from Thebes to Amarna, Nefertiti moved with him. She was a full participant in important religious ceremonies: when Akenhaten appeared in public to make religious offerings to Aten, the sun god, Nefertiti performed them with him. And when Akenhaten ordered colossal statues of himself, he would order statues of equal size for his 'Great Wife'. Nefertiti was seen as second only to the pharaoh himself. All you need is love The reason for this may have been simple: love. In an age when marriages were arranged for political reasons, the partnership between Akenhaten and Nefertiti seems to have been unusually romantic. Nefertiti is also the only Egyptian queen that we know to have been lovingly described by her husband, the pharaoh. Their home life appears to have been a happy one. She bore Akenhaten six daughters and images still exist of the pharaoh and his wife kissing and playing with their children. The vanishing All appeared well. The move to Amarna was a success and life seemed good. Then, in the twelfth year of Akenhaten's reign and at the height of Nefertiti's powers, she vanished from history altogether. Until 1822, when scholars learned how to read hieroglyphics, she simply ceased to exist. Found again Despite this breakthrough, Nefertiti remained faceless for almost another century, until 1912. A German archaeologist called Ludwig Borchardt was digging through the remains of Amarna and found a life-sized bust of the long-dead queen. As Borchardt recorded in his diary, "Description is useless, see for yourself." Nefertiti lived up to her name, 'a beautiful woman has come'. Today, scholars still don't know exactly why she so suddenly disappeared from history more than 3,000 years ago. Tiy Born a commoner, Queen Tiy soon became the near equal of her husband, Pharaoh Amenhotep III and was even worshipped as a god. To strengthen the bloodline of the royal family, pharaohs would usually marry close female relatives. Amenhotep III chose to break with convention by marrying Tiy, a commoner. He announced the news on a stone scarab - a small insect-shaped stone, engraved with letters and used to carry news across the empire. Common get it The daughter of Yuya, a chariot officer, and Thuya, a queen's servant, Tiy would have been familiar with the pharaoh's court, but she was still a commoner. Any lesser woman might have been intimidated by her sudden rise to fortune. Not Tiy. The traditional role of a queen was passive - to pleasure the king and provide him with an heir. Tiy wanted more than this. Stand by your man To his credit, Amenhotep realized the value of having a strong, intelligent woman by his side and was happy to agree to her wishes. Tiy soon became central to her husband's reign and, effectively, became his second-in-command. Almost as soon as they were married, Tiy was mentioned in the stone dispatches sent out by Amenhotep to foreign kings and princes. Even more unusually, foreign kings were prepared to deal with her on official business and wrote to Tiy as an equal, ignoring her gender and humble birth. R.E.S.P.E.C.T. Women were treated with far more respect in Egypt than in most other countries at this time. But for a woman to have such an important political role was rare. Abroad, it must have been almost unbelievable. As her stature grew, so did her statues. On carved images on temple walls, Tiy rapidly increased in size until she was shown alongside - and often as large as - pictures of her husband, the pharaoh. This was an enormous compliment and demonstrated to his people how much Amenhotep respected his wife and regarded her as his near-equal. Till death us do part Remains of Amenhotep III and Tiy's temple His respect for Tiy led the pharaoh to build two huge temples in the south, by the Nile in Nubia. One temple was built for Amenhotep; the second was built for Tiy. However, the two temples at Soleb were not just built for the pharaoh and his wife; they were also dedicated to them. Deep in this southern part of the Egyptian empire, Amenhotep and Tiy were not just obeyed as rulers but were also worshipped as gods. Tiy outlived her pharaoh husband and remained a respected and powerful figure during the reign of her son, Amenhotep IV, or Akenhaten. Nefertari Little is known of Nefertari, the first chief queen of Ramesses the Great, but her stunning tomb is a testament to the high regard in which her husband held her. Like his predecessors, Ramesses II had an entire harem, but at any one time, just one wife was given the rank of chief queen. His very long reign saw one consort die after another and Ramesses would ultimately take eight principal wives. The first and most beloved of these was Queen Nefertari. Thought to be an Egyptian noblewoman, Ramesses married Nefertari in 1312 BC and she soon gave him his first son, Amenhirwenemef - the first of 11 children. Crazy in love Although Ramesses was primarily in love with himself, he was also devoted to Nefertari and wrote at length of his love and her beauty. He demonstrated this by building her a magnificent tomb, the finest in the Valley of the Queens. Although the tomb was later looted of its treasures, its decoration was exquisite. The walls were covered with intricate paintings using a vast array of colors. It also featured 'relief carving', a tricky process where the design is carved to stick out from the surface of the wall. Going the extra mile When Nefertari died, she was sealed into her tomb as was customary. Ramesses then ordered two enormous temples to be built, carved out of the cliffs of Abu Simbel in Nubia, south of Thebes. The larger of the two temples was built for Ramesses himself; the smaller temple was built for Nefertari. The façade of the temple featured two enormous carvings of Nefertari. However, just to remind his people who was boss, these carvings were outnumbered by four images of Ramesses himself, even bigger than those of his wife. There was also an inscription stating that Ramesses II paid for the temple "for the Chief Queen Nefertari... for whom the sun shines." Who's the man? The temples had another purpose: they were a gigantic piece of propaganda. Located at the most southern point of the Egyptian empire, they were intended to demonstrate the pharaoh's power to locals and visitors alike. Visible for miles, the temples and colossal statues of Ramesses and Nefertari would have filled travelers with wonder and awe - just the reaction Ramesses wanted and a fitting tribute to his beloved wife, Nefertari.