1AC - openCaselist 2015-16

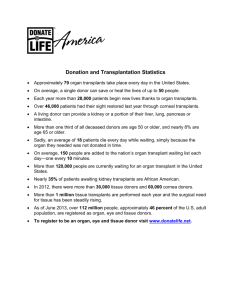

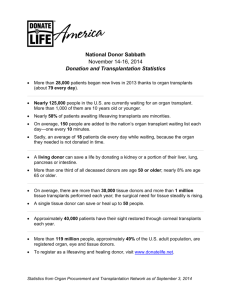

advertisement