Family Presence during Resuscitation

advertisement

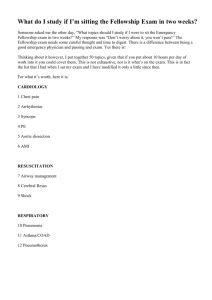

Running head: FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION Family Presence during Resuscitation Pamela Green, MSN, APRN, FNP-C Linda Roussel, PhD, RN, NEA-BC, CNL University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) School of Nursing 1 FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION 2 Family Presence during Resuscitation Introduction Background The last few moments of life are often marked by heroic efforts to restore cardiopulmonary function. Varying opinion surround the issue of family presence in the resuscitation room while these efforts are underway. Family members and healthcare providers are at odds regarding what is best in those critical moments. With trained medical personnel immediately available to implement cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), 44% of patients will die within the first 20 minutes post CPR (Peberdy et al., 2003). Of the 56% who survive, less than 17% will survive to discharge from the hospital (Weissman & Ramenofsky, 2009). Although CPR is often the terminal life event, less than five percent of acute care facilities across the United States have policies and protocols to allow for family presence in the resuscitation room (MacLean et al., 2003). The purpose of this quality improvement project is to determine if awareness of the benefits of and guidelines for family presence in the resuscitation room has a positive impact on physician opinion. Literature Search Strategy A search of the literature surrounding family presence during resuscitation was undertaken. Database, citation and hand searching methods were used. Database searches included Cochrane Library, CINAHL, Scopus, Medline Plus, Ovid and PubMed. Hand searches of journals included Journal of Emergency Nursing, BMJ Supportive and Palliative Care, Centers to Advance Palliative Care, and the American Journal of Critical Care. Key search FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION 3 words included: family presence, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, healthcare provider stress, family grieving, and family in resuscitation room. Literature Synthesis In December, 2012, the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA) revised their guidelines recommending family members be included during invasive procedures and resuscitation (Emergency Nurses Association [ENA], 2012). The American Heart Association recommended family members be offered the opportunity to be present during resuscitation (American Heart Association [AHA], 2000). These guidelines and recommendations were followed by a practice alert from the American Association of Critical Care Nurses stating all family members should be given the option of family presence during resuscitation (American Association of Critical Care Nurses [AACN], 2010). Healthcare consumers are a driving force calling for change in organizational culture to include family presence during resuscitation. When allowed to be present, family members perceive the experience to have a positive effect on grieving and adjusting to loss (Doyle et al., 1987; Meyers et al., 2000; Meyers, Eichhorn, & Guzzetta, 1998). The Emergency Nurses Association (ENA) conducted a review of the literature surrounding family presence during resuscitation and invasive procedures. The first retrospective study to examine family presence during resuscitation was performed in 1985 at Foote Hospital in Jackson, Michigan. This study indicated family presence during resuscitation had a benefit in family member grieving and that family members perceived they helped the person undergoing resuscitation (Doyle et al., 1987). Since 1987, family presence has been studied from the family member and healthcare provider perspective. Of the 37 articles reviewed, only one qualitative study was found to have been conducted of resuscitation FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION 4 survivors. This study found all survivors were content with family presence during resuscitation (Robinson, Mackenzie-Ross, Hewson, Egleston, & Prevost, 1998). Hospitalized patients with life threatening illness indicated they would prefer family to be present during CPR (Mortelmans et al., 2009). No studies indicated decrease in family member satisfaction or increase in stress when present during resuscitation. From the family member perspective, many expressed they not only wanted to be present, but felt it was their right (Tinsley et al., 2008; Mortelmans et al., 2009; Piira, Sugiura, Champion, Donnelly, & Cole, 2005; Dingeman, Mitchell, Meyer, & Curley, 2007; Dudley et al., 2009; McGahey-Oakland, Lieder, Young, & Jefferson, 2007). Allowing family presence during the resuscitation was felt to create transparency. Family members who had witnessed a resuscitation event felt everything had been attempted to save their loved one (McGahey-Oakland et al., 2007; Tinsley et al., 2008; Emergency Nurses Association [ENA], 2007). Healthcare providers have varying opinion regarding family presence during resuscitation (FPDR). Many providers have held to the belief that witnessing resuscitation efforts would be too stressful for family members or family presence would hinder the delivery of care. Increased risks of litigation and increased stress to healthcare providers have also been cited as compelling reasons to separate patient and family during resuscitation efforts (Critchell & Marik, 2007). One study of healthcare providers in the emergency and critical care areas revealed providers were 82% in favor of family presence during resuscitation despite the fact they had no prior knowledge of the benefit and were not aware of guidelines surrounding family presence (Demir, 2008). Healthcare providers identify family presence allows the family the opportunity to say goodbye when resuscitation efforts are unsuccessful, promotes family acceptance of their FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION 5 loved one’s death, and facilitates grieving (Dingeman et al., 2007; Demir, 2008; McClement, Fallis, & Pereira, 2009; Walker, 2008). Many healthcare providers perceive untoward repercussions when family members are allowed to be present in the resuscitation room. Many providers believe family members would interfere with resuscitation efforts (Basol, Ohman, Simones, & Skillings, 2009; Demir, 2008; Dingeman et al., 2007; Fernandez, Compton, Jones, & Vilella, 2009; McClement et al., 2009; Walker, 2008; Madden & Condon, 2007). Healthcare providers experience increased stress and performance anxiety when family members are witnessing the resuscitation efforts (Basol et al., 2009; Demir, 2008; Dingeman et al., 2007; Fernandez et al., 2009; Madden & Condon, 2007; McClement et al., 2009; Walker, 2008). Although there is no evidence to support the perception, many providers fear increased litigation when family members are present in the resuscitation room (Walker, 2008; Madden & Condon, 2007; McClement et al., 2009; Dingeman et al., 2007; Demir, 2008; Fernandez et al., 2009). Approximately 95% of acute care facilities in the United States do not have policies in place to support family presence during resuscitation (MacLean et al., 2003). Three studies indicated hospital policy surrounding family presence would have a positive impact on provider attitude regarding family presence (Basol et al., 2009; Madden & Condon, 2007; Howlett, Alexander, & Tsuchiya, 2010). Based on review of the literature, it is the recommendation of the ENA that family members should be offered the option for presence in the resuscitation room. The ENA further recommends that institutional policy should be written to support the recommendation of family presence during resuscitation. There is evidence to support a designated health care professional being assigned to family members present in the resuscitation room to provide explanation and comfort (Emergency Nurses Association [ENA], 2012). FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION 6 Microsystem Analysis Baylor Health Care System does not have a written policy for family presence during resuscitation. Interviews with physicians and staff members in the Emergency Department and Critical Care areas reveal variation in practice between departments and providers. Provider opinion regarding family presence in the resuscitation room ranges from “never” to “always”. Of those providers allowing family presence, no clear criteria could be elicited. Decisions appear to be subjective based on the opinion of the provider. One provider who reported he never allowed family members to be present in the resuscitation room commented, “I know I am going to have to change my practice. Evidence is mounting in support of family member presence”. Study Question For physicians in the acute care setting, does education on recommendations and best practice related to family presence in the resuscitation room change physician opinion regarding family presence? Purpose and Objectives The purpose of this project is to determine if awareness of the benefits of and guidelines for family presence in the resuscitation room has a positive impact on physician opinion. The objectives of this project include: 1) identify current practice related to family presence in the resuscitation room, 2) identify medical staff opinion regarding family presence in the resuscitation room, and 3) determine if education regarding guidelines and best practice for family presence during resuscitation has a positive impact on medical staff opinion. FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION 7 Conceptual Framework Medical practice struggles to keep up with medical knowledge. It is estimated to take as long as twenty years to incorporate evidence into practice (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2001). Donabedian’s model for healthcare quality (Appendix A) identifies three fundamental elements of healthcare when seeking to incorporate evidence into practice: 1. Structure – characteristics of the organization where care occurs, 2. Process – the focus of the care delivered to the patient, and 3. Outcome – effect of care on the patient (Donabedian, 1988). Applied to family presence during resuscitation, the structure may include available staff, the physical environment where resuscitations occur, equipment available and the organization philosophy regarding family presence. Based on the location of the patient within the facility when a cardiopulmonary resuscitation occurs, some variables within the structure may change. The process for family presence must view the patient/family unit as the focus of care. Not only will measures continue to surround patient outcome in terms of survival, outcomes for family members must be developed to capture the outcome of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The Model for Improvement identifies that improvement comes from the application of knowledge. The Model for Improvement (Appendix B) provides a framework for change. This model is based on three questions that form the basis for improvement: What are we trying to accomplish? How will we know that a change is an improvement? What changes can we make that will result in improvement? Addressing why improvement is necessary, establishing and incorporating a means to identify when improvement is happening, developing a change resulting in improvement, testing FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION 8 the change before implementation and knowing when and how to make change permanent are the principles guiding the Model for Improvement (Langley et al., 2009). The methodological framework of the Model for Improvement (MFI) will be used to determine the effectiveness of education. The three fundamental questions from MFI will guide the improvement project through Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) (Langley et al., 2009). 1. What are we trying to accomplish? The goal of this project is to determine if awareness of current guidelines and best practice have an impact on medical staff opinion regarding family presence in the resuscitation room. 2. How will we know a change is an improvement? To assess improvement in physician opinion regarding family presence during resuscitation, the following aims will be developed: a. Baseline assessment to determine current medical staff opinion regarding family presence in the resuscitation room. b. Evidence based education regarding guidelines, recommendations, and benefits of family presence during resuscitation. c. Comparative analysis of pre- and post-education provider opinion of family presence during resuscitation. 3. What change can we implement that will result in an improvement? Medical staff education to support the practice of family presence during resuscitation will be developed and implemented. Setting Baylor Medical Center at Carrollton (Baylor Carrollton) is a non-profit organization in the Dallas/Ft.Worth, Texas area. Joining Baylor Health Care System (BHCS) in June, 2009, the FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION 9 organization is one of 31 care facilities owned, operated, joint ventured or affiliated with BHCS. Baylor Carrollton maintains 232 licensed acute care beds. Five hundred six physicians are on the medical staff that provides full services to the community of Carrollton and Farmers Branch, Texas. IRB The Clinical Ethics and Supportive and Palliative Care Committee identified an opportunity to facilitate change in the Baylor Health Care System (BHCS) approach to family presence in the resuscitation room. The Advanced Practice Registered Nurse (APRN) for Supportive and Palliative Care at Baylor Medical Center at Carrollton acted as lead facilitator for this project. Approval from BHCS and the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) institutional review boards was obtained prior to the initiation of this project. Population Active and courtesy medical staff members from Baylor Carrollton were asked to complete two electronic surveys. The purpose of the surveys was to identify medical staff opinion regarding family presence during resuscitation before and after review of the evidence surrounding family presence during resuscitation. A total of 239 surveys were sent. Inclusion criteria: Baylor Carrollton active or courtesy medical staff with an email address on file in the Medical Staff Office. Participants must be able to read English. Participants must hold a license as a physician in the state of Texas. Physicians in practice residency programs were asked to participate. Exclusion criteria: FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION Retired members of the Baylor Carrollton medical staff. Baylor Carrollton medical staff members in nonclinical positions. Baylor Carrollton medical staff members in research positions. Active and courtesy staff members with no email address on file in the Medical 10 Staff Office. Plan The plan for this improvement project began with a literature review of the evidence surrounding family presence. The target population was clearly identified with defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The project cover letter, survey and education information was developed. Consent to survey the target population was granted through the Institutional Review Boards for Baylor Health Care System and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The survey utilized a 4-point Likert scale. Participants were asked to rate their agreement with 12 statements. These statements were designed to capture the participant’s opinion regarding family presence in the resuscitation room. Answers ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The survey was adopted from the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA, 2007) study developed and published by Lori M. Feagan. Internal validity of the survey was established by a panel of three masters and doctoral prepared nurses (Feagan & Fisher, 2011). The survey identified eight project variables of provider support of family presence during resuscitation. The overall internal reliability of the variables was established with a Cronbach a value of .884. The variables included participant opinion regarding: 1. family member emotional trauma with witnessed resuscitation efforts 2. family member likelihood to file lawsuit with witnessed resuscitation efforts 3. family member satisfaction in care with witnessed resuscitation efforts FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION 11 4. family member interference or interruption of care with witnessed resuscitation efforts 5. anxiety of health care provider with family members witnessing resuscitation efforts 6. family member presence inhibiting code team member communication 7. family members should be given the option to be present during resuscitation efforts 8. family members have the right to be present during resuscitation efforts (Feagan & Fisher, 2011). Demographic questions captured data to include gender, practice area, and prior education related to family presence during resuscitation. Additional data elements identified participant’s years in practice, number of resuscitation efforts performed in the past year, and number of resuscitation efforts with family members present. Do Two hundred and thirty nine members of the Baylor Carrollton medical staff received information via email regarding the study and a link to complete the first on line survey. The survey link was available for 14 days. On day 15, a ten slide Family Presence presentation along with four slides of references was sent to the same 239 members of the Baylor Carrollton medical staff via email with instructions to review the presentation prior to completing the second on line survey. The second survey link was available for 14 days. Completed survey results were restricted to the project leader. Survey results were entered by the project leader into an IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences data analysis program. No participant identifiers were collected. FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION 12 Study Thirteen percent of medical staff participated in the study (n = 32). Percentage based on gender and practice area are provided in Figure 1. Family Presence during Resuscitation Demographics 87.5% 46.9% 12.5% Male Female 21.9% 25% 3.1% ED ICU GIP Womens Service Pedi 3.1% Figure 1 – Participant demographics Fifty-nine percent of participants participated in five or less resuscitations over the previous year. Providers in the Emergency department were more likely to participate in CPR events than those in the Intensive Care Unit or General In Patient areas, as seen in Figure 2. Based on the results from the initial survey, 88% of participants had little or no experience with family presence in the resuscitation room, 79% had received no training regarding family presence and 68% felt the healthcare system had a policy in place to address family presence during resuscitation. Family Presence during Resuscitation CPR in the Past Year 83% 67% 20% ED ICU GIP Figure 2- CPR events Responses from the first survey (n = 19) were compared to the responses from the second survey (n = 13). There was no change in provider opinion between the two surveys related to FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION 13 providers wanting to be present during CPR of a loved one and caregiver anxiety and/or stress with family members present. When responding to the statement regarding advocating for family presence during resuscitation, 22.2% of survey one respondents were in agreement, as opposed to 53.8% in survey two. Other indicators reflecting change between first and second survey are provided in Table 1. Indicator Family members should have the option to be present during CPR Family members present for CPR have fewer psychological difficulties during bereavement FPDR results in higher rates of family satisfaction with care Witnessing CPR causes emotional trauma to family members Family members who witness CPR are more likely to file lawsuit FPDR inhibits code team communication FPDR interferes or interrupts care Comfort with providing psychosocial-spiritual support for family members during CPR Table 1 – Comparison data % Agree and Somewhat Agree Survey #1 % Agree and Somewhat Agree Survey #2 55.6% 69.2% 13.6% increase 50.0% 53.9% 3.9% increase 55.6% 69.2% 13.6% increase 72.2% 53.8% 18.4% decrease 41.2% 7.7% 33.5% decrease 61.1% 46.2% 22.6% decrease 61.1% 38.5% 19.4% decrease 66.6% 76.9% 10.3% increase Outcome A stepwise linear regression analysis was performed to determine predictors of family presence during resuscitation as an option. The dependent variable was family member option for presence during resuscitation. There were eleven independent variables included in the analysis. All variables satisfied the level of measurement requirements for stepwise multiple FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION 14 regression analysis. Survey respondents who viewed family presence as an option did not identify family presence as interfering with care (p <.001), viewed family presence as a right (p <.001), and felt there was a positive psychological effect for family members being present (p =.044). A parsimonious subset of independent variables was identified to be statistically significant in predicting agreement with family presence as an option. These included, in order of importance: 1. Advocacy for family presence. 2. Family presence does not interfere with care. 3. Right of family presence. 4. Psychological benefit of grieving with family presence (when advocacy for family presence removed). These four predictors accounted for 86% of the variance for the option of family presence during resuscitation. F (3, 24) = 14.05, p < .001, R2 = .856, 95% CI Limitations of this study include sample size. The design of the study did not control for participant consistence between the survey groups. There was no means to verify education slides were reviewed prior to completing the second survey. Fifty-four percent (54%) of participants completing the second survey denied having education or training on family presence, suggesting an alternate form of education may have had a greater influence on second survey outcomes. Conclusion Based on this limited study, physician opinion does appear to be impacted by the presentation of evidence supporting practice change. Participants completing the post education FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION 15 survey were more supportive of family presence in the resuscitation room, indicating education across the healthcare system would be beneficial prior to developing a policy for family presence during resuscitation. The next phase in the implementation of family presence during resuscitation will be the development of a team focused on family presence during resuscitation. Healthcare provider champions for change will be identified. This team should include all stakeholders involved in a resuscitation event. Including a patient or family member who has experienced or witnessed cardiopulmonary resuscitation as a member of the team should be strongly considered. It will be the responsibility of this team to develop a protocol for family presence with the goal of piloting the process in the critical care and emergency department areas within three acute care facilities across the system. Identifying healthcare provider champions at each facility will be invaluable to the transition of Baylor Health Care System from family exclusion to family inclusion during resuscitation. . FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION 16 References Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2001). Translating research into practice (TRIP) II. Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/factsheets/translatnig/tripfac/trip2fac.pdf American Association of Critical Care Nurses. (2010). American Association of Critical Care Nurses Practice Alert: Family presence during resuscitation and invasive procedures. Retrieved from http://www.aacn.org/wd/practice/docs/practicealerts/family%20presence%20042010%20final.pdf American Heart Association. (2000). Guidelines 2000 for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care, part 2: ethical aspects of CPR and ECC. Circulation, 102, 112-121. http://dx.doi.org/Retrieved from Basol, R., Ohman, K., Simones, J., & Skillings, K. (2009). Using research to determine support for a policy on family presence during resuscitation. Dimensions in Critical Care Nursing, 28, 237-247. Chelluri, L. P. (2008, April-June). Quality and performance improvement in critical care. Indian Journal of Critical Care , 12, 67-73. Retrieved from http://www.bioline.org.br/pdf?cm08016 Critchell, C. D., & Marik, P. E. (2007). Should family members be present during cardiopulmonary resuscitation? A review of the literature. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 24, 311-317. Demir, F. (2008, August). Presence of patients’ families during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: physicians’ and nurses’ opinions. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 63, 409-416. FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION 17 Dingeman, R. S., Mitchell, E. A., Meyer, E. C., & Curley, M. A. (2007, October). Parent presence during complex invasive procedures and cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A systematic review of literature. Pediatrics, 120, 842-854. Donabedian, A. (1988). The quality of care: how can it be assessed? JAMA, 206(12), 1743-1748. Doyle, C. J., Post, H., Burney, R. E., Maino, J., Keefe, M., & Rhee, K. J. (1987, February 3). Family participation during resuscitation: an option. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 16:6, 673-675. Dudley, N. C., Hansen, K. W., Furnival, R. A., Donaldson, A. E., Van Wagenen, K. L., & Scaife, E. R. (2009). The effect of family presence on the efficiency of pediatric trauma resuscitations. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 53, 777-784. Emergency Nurses Association. (2007). Presenting the Option for Family Presence. Des Plains, IL: Emergency Nurse Association. Emergency Nurses Association. (2012). Clinical Practice Guideline: Family presence during invasive procedures and resuscitation . Retrieved from https://www.ena.org/practiceresearch/research/CPG/Documents/FamilyPresenceCPG.pdf Feagan, L. M., & Fisher, N. J. (2011, May). The impact of education on provider attitudes toward family witnessed resuscitation. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 37, 231-239. Retrieved from http://www.nursingconsult.com/nursing/journals/0099-1767/fulltext/PDF/s0099176710001108.pdf?issn=00991767&full_text=pdf&pdfName=s0099176710001108.pdf&spid=24209537&article_id=8 12771 FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION 18 Fernandez, R., Compton, S., Jones, K. A., & Vilella, M. A. (2009). The presence of a family witness impacts physician performance during simulated medical codes. Critical Care Medicine, 37, 1956-1960. Howlett, M. S., Alexander, G. A., & Tsuchiya, B. (2010). Health care providers’ attitudes regarding family presence during resuscitation of adults: An integrated review of the Literature. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 24, 161-174. Kitson, A., Harvey, G., & McCormack, B. (1998). Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: A conceptual framework. Quality in Health Care, 7, 149-158. Retrieved from http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/7/3/149.full.pdf+html Langley, G. J., Moen, R. D., Nolan, K. M., Nolan, T. W., Norman, C. L., & Provost, L. P. (2009). The improvement guide: A practical approach to enhancing organizational performance (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Langley, G. J., Moen, R., Nolen, K. M., Norman, C. L., & Provost, L. P. (2009). The Improvement Guide: A practical approach to enhancing organizational performance (2 ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. MacLean, S. L., Guzzetta, C. E., White, C., Fontaine, D., Eichhorn, D. J., Meyers, T. A., & Desy, P. (2003, June). Family presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation and invasive procedures: practices of critical care and emergency nurses. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 29:3, 208-221. Madden, E., & Condon, C. (2007). Emergency nurses’ current practices and understanding of family presence during CPR. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 33, 433-440. McClement, S. E., Fallis, W. M., & Pereira, A. (2009). Family presence during resuscitation: Canadian critical care nurses perspectives. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 41, 233-240. FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION 19 McGahey-Oakland, P. R., Lieder, H. S., Young, A., & Jefferson, L. S. (2007). Family experiences during resuscitation at a children’s hospital emergency department. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 21, 217-225. Meyers, T. A., Eichhorn, D. J., & Guzzetta, C. E. (1998, October). Do families want to be present during CPR? A retrospective survey. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 24:5, 400405. Meyers, T. A., Eichhorn, D. J., Guzzetta, C. E., Clark, A. P., Taliaferro, E., Klein, J. D., & Calvin, A. (2000). Family presence during invasive procedures and resuscitation. American Journal of Nursing, 100:2, 32-42. Mortelmans, L. J., VanBroeckhoven, V., Van Boxstael, S., De Cauwer, H. G., Verfaillie, L., Van Hellemond, P. L., ... Cas, W. M. (2009, August). Patients’ and relatives’ view on witnessed resuscitation in the emergency department: A prospective study. European Journal of Emergency Medicine, 17, 203-207. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328331477e Peberdy, M. A., Kaye, W., Ornato, J. P., Larkin, G. L., Nadkami, V., & Mancini, M. E. (2003). Cardiopulmonary resuscitation of adults in the hospital: A report of 14,720 cardiac arrests from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation, 58 (3), 297308. Piira, T., Sugiura, T., Champion, G. D., Donnelly, N., & Cole, A. S. (2005). The role of parental presence in the context of children’s medical procedures: A systematic review. Child: Care, Health & Development, 31, 233-243. FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION 20 Robinson, S. M., Mackenzie-Ross, S., Hewson, G. L., Egleston, C. V., & Prevost, A. T. (1998). Psychological effects of witnessed resuscitation on bereaved relatives. Lancet, 352, 614619. Rycroft-Malone, J. (2004). The PARIHS framework - A framework for guiding the implementation of evidence based practice. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 19, 297304. Tinsley, C., Hill, J. B., Shar, J., Zimmerman, G., Wilson, M., Feier, K., & Abd-Allah, S. (2008). Experience of families during cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics, 122, 799-804. Walker, W. (2008). Accident and emergency staff opinion on the effects of family presence during adult resuscitation: Critical literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 61, 348-362. Weissman, D. E., & Ramenofsky, D. H. (2009). Fast Facts and Concepts #179. Retrieved from Medical College of Wisconsin End of Life/Palliative Education Resource Center: http://www.eperc.mcw.edu/EPERC/FastFactsIndex/ff_179.htm FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION Appendix A Donabedian’s Model For Health Care Quality 21 FAMILY PRESENCE DURING RESUSCITATION Appendix B 22