MSA THE RESEARCH COLUMN April 2014

advertisement

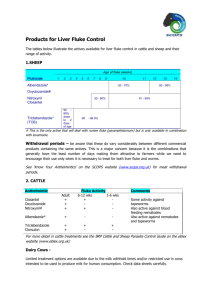

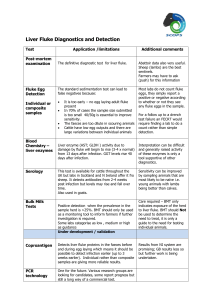

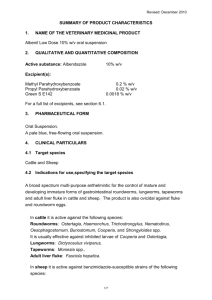

THE RESEARCH COLUMN: April 2014. by Heinz H. Meissner Fasciolosis or liver fluke has been identified in South Africa as a major concern for pasturebased dairy production systems, with many reports from the south-eastern seaboard areas. It sometimes also appears if control and treatment may be ineffective. Concerned farmers as a result have inquired whether dedicated research into the problem is not warranted. I therefore decided to consult the literature and speak to prominent scientists to try and understand and maybe suggest an approach. Worldwide liver fluke infestation is one of the most important parasitic diseases of cattle, not only economically, but also due to its eroding effect and comparatively ineffective control measures. In South Africa it is mainly caused by Fasciola hepatica and to a lesser extent F. gigantica. The fluke requires an intermediate host for completion of its lifecycle in the form of lymnaeid snails, which it invades after being shed through the cattle faeces. Control methods include managerial measures to limit the occurrence of the snail and drug therapy at critical stages of the lifecycle of the fluke. The development of a vaccine has received attention, but with limited success which probably implies that we will have to wait much longer before a suitable vaccine comes onto the market. Managerial measures to limit the prevalence of the snail host include borehole water in troughs instead of drinking at springs or marshy areas, fencing off of marshy areas, grazing such areas only when the numbers of the snail is low etc. In the past, efforts to control snail numbers include spraying with molluscicides, copper sulphate and salt, but these methods are not recommended because of negative environmental impact – the use of molluscicides has in fact been banned. Thus, if the snail is to be controlled it will have to be through biological means by organisms which are specific. Some success to that effect has been reported in Brazil with the fungus Pochonia chlamydosporia. Drugs on the market include albendazole, clorsulon, nitroxinyl, oxyclozanide and triclabendazole. Oxyclozanide is available in South Africa since the sixties and used in dairy cattle because it does not require a milk withdrawal period. It is commercially available as Levisan, Nem-A-Fluke and Tramizan. An advantage of these products is that they in addition to oxyclozanide also contain levamizole which is a broad spectrum remedy against most round worms. Some of the other drugs require a long withdrawal period or is not at all suitable or practical for dairy cattle. A recent problem is resistance of the fluke to some of the drugs, notably clorsulon and triclabendazole. Alternative use of triclabendazole and the combination drug triclabendazole plus oxfendazole apparently delays the resistance response. However, since protective immunity is not obtained by the animal, repeated drug therapy is required which may enhance fluke resistance. To combat resistance research into new generation drugs is certainly possible but not likely to happen because of prohibitive costs. Already in 1994 the discovery of a promising substance and the eventual development of a broad spectrum worm remedy from it cost US $230 million! Notwithstanding the control measures discussed above, identification of the fluke and the snail species and their prevalence in time and space on individual farms appears necessary to recommend more effective control. This can be supported by modern ELISA immunological methods of Fasciolosis diagnosis where the antigen or antibody is detected in serum or milk and by inspection of animal livers where animals need to be slaughtered. Such a monitoring program should be initiated. Over the longer term it appears worthwhile to initiate a program of controlling the snail host. As the Brazilian approach has shown, biological enemies may be the way to go, although it does not rule out other innovative methods. Literature and expertise consulted Dias, A.S. et al., 2013. Pochonia chlamydosporia in the biological control of Fasciola hepatica in cattle in Southeastern Brazil. Parasitol. Res. 112, 2131-2136. Gratwick, W., 2014. Liver fluke in the UK. Unpublished document provided upon request. Malan, F.S., 2014. Liver fluke relevance and control strategies (small stock and cattle) – including practical application and limitations of fluke serology. LHPG, Veterinary Society of South Africa. McKellar, Q.A., 1994. Chemotherapy and delivery systems – helminths. Vet. Parasitology 54, 249-258. Vanderleek, M., 2014. E-mail information Van Wyk, J. 2014. Consultation and e-mail information