Running head: SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO

advertisement

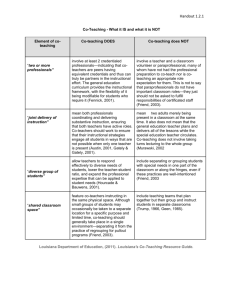

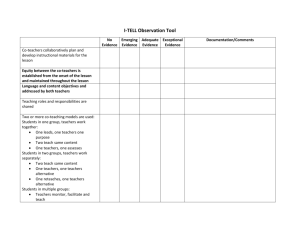

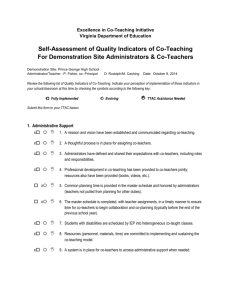

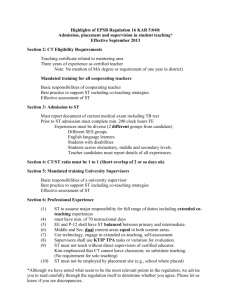

Running head: SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS Secondary Special Education Co-Teachers Speak Out 1 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS Abstract A random sampling of middle and high school special education co-teachers in three states responded to content on a co-teaching survey. The survey was designed so that co-teachers could respond to each of their multiple co-teaching situations. Results indicate that.... 2 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS Co-teaching is being used more frequently as a service delivery model for students with disabilities and other diverse learning needs. Studies on co-teaching focus on interpersonal co-teaching relationships between general and special educators, the amount of time provided for co-planning, and the extent to which co-teachers use varied co-teaching models for instruction (Bouck, 2007; Magiera & Zigmond, 2005). Magiera and Zigmond concluded that all students receive more instructional interactions under co-teaching conditions. However, general educators interact less frequently with students with disabilities when special education teachers were in the classroom. Bouck found that co-teaching resulted in both desired and undesired impacts. For example, she noted co-teaching created freedom and constrained teachers’ autonomy; offered assistance for students but could sometimes devalue teachers’ roles; and offered new role opportunities for some teachers while also supporting or limited existing roles. In a metasynthesis of thirty-two qualitative investigations of co-teaching in inclusive classrooms at the secondary level, Scruggs, Mastropieri, and McDuffie (2007) concluded that co-teachers were generally supportive of co-teaching as a service delivery model, although a number of important needs were identified including: teacher preparation, sufficient planning time, and mastery of content by special education teachers. The researchers also identified that some version of “one teach, one assist,” which has one co-teacher as a lead and the other in the role of assisting versus leading instruction, was the most utilized model of co-teaching reported in their investigations by a considerable margin. The general education teacher was most often the lead teacher, while the special education teacher usually moved about the classroom interacting with individual students as needed. Isherwood and Barger-Anderson (2008) concluded that interpersonal relationships among co-teachers, clearly defined roles and responsibilities, and administrative support and validation are factors that affect the development of successful co-teaching relationships. 3 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS They also found that the frustration of special education teachers with their lack of content knowledge led to anxiety that contributed to dysfunctional co-teaching relationships. General education teachers consistently indicated that they did not feel comfortable delegating instructional roles to special education teachers, and considered that a division of responsibilities would be professionally disrespectful. Giving teachers a voice about the coteacher with whom they will instruct all students is a starting point for successfully implementing co-teaching models in schools. It is also critical for teachers to accept the redefining of the traditional roles to which they are accustomed. For example, neither coteacher may be accustomed to planning with someone else, teaching differently, or having someone else talking to students when new content is presented. Nonetheless, these behaviors are hallmarks of effective co-teaching situations. Successful co-teachers learn from each other in ways that blend, versus stifle, each teacher’s pedagogical knowledge and skills. Teacher Pedagogy Most current research indicates that special educators are left with insufficient opportunities to use their strong pedagogical skills with students who need those skills the most, because general educators lead the content instruction (McDuffie, Mastropieri, & Scruggs, 2009; Moin, Magiera, & Zigmond, 2009; Murawski, 2006). For example, Moin, Magiera, and Zigmond investigated whether classes with two teachers delivering science education were better than solo-teaching in addressing the needs of students with learning disabilities. The researchers used a narrative observation protocol to measure student interactions, such as what the teachers were doing, what the students were doing, the organization of the class, and the materials used. For teacher interaction, interviews were conducted to elicit teachers’ experiences with co-teaching and their general perceptions of the co-teaching model including benefits, drawbacks, and possible improvements. Results indicated that the instability of the co-teacher pairs as well as the special education teachers’ 4 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS science knowledge affected the co-teaching relationships. Participants indicated that the previous years’ co-teaching occurred with different co-teachers, and they would prefer permanence of pairs to improve instruction and exchanging of expertise. In the successful co-teaching cases, the special educators’ content knowledge was acquired through prior training or gained through continuity with the same general education teacher over many years. Lack of co-teaching training in pairs also had an effect on the general education teachers’ awareness of special education curricular adaptations. For example, one general educator shared that she did not really adapt her teaching style for individual students; she taught the same way for all students. Clearly pedagogical decisions were either not made in concert with the special educator as part of co-planning, or the general educator’s decisions regarding pedagogy seem more unilateral versus collaborative. Such situations can be evidence of the lack of parity the two educators experience, which is a concern in some coteaching situations. Parity in the Classroom Multiple studies found that the special educators’ co-teaching role is more of an instructional assistant than an instructional equal with general education content teachers (Moin, Magiera, & Zigmond, 2009; Scruggs et al., 2007). Hang and Rabren (2009) examined teachers’ perspectives of co-teaching revealing that 90% of the general educators and 93% of special educators believed they were primarily responsible for monitoring students’ behaviors. These results prompt the question: If both general education and special education teachers think they are primarily responsible for managing students’ behavior, does there need to be clarification of these responsibilities among co-teachers? The researchers suggest that this problem may be a result of insufficient planning time. Harbort et al. (2007) focused on teacher interactions and examined roles and actions of members of co-teaching teams consisting of special educators and general educators in the 5 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS high school setting. The researchers found that special educators’ role was primarily confined to monitoring students’ behaviors. However, this is not the most effective use of highly-trained special educators because their expertise is not being maximized. The researchers found that special educators were interacting with the large group during instruction 43% of the time, mostly in a monitoring role. In addition, the general education teachers spent 30% of the time presenting information to students, whereas special educators spent less than 1% of the time presenting information. Scheeler, Congdon, and Stansberry (2010) found that co-teachers giving immediate corrective feedback via bug-in-ear (BIE) technology on a specific teaching behavior in general education classroom settings increases engagement in the instructional process and parity of both teachers in a co-teaching team. Their results show that immediate corrective feedback delivered by peer coaches using BIE technology was effective in increasing effective teaching techniques. Moreover, the co-teachers’ behaviors were maintained across time and generalized across settings. Teachers were receptive of the BIE device as a nonintrusive, efficient way to deliver and receive feedback in real time. Buckley (2005) conducted a qualitative study examining how general and special education teachers perceive their roles in middle school co-taught classrooms. Results indicated that the special education teachers believed that they were a benefit to both students with learning disabilities (LD) and without disabilities because of the special educators’ knowledge of strategies and accommodations. The special educators felt a collaborative relationship involved experts in different areas and perceived their general education counterparts as being responsible for content area instruction in the classroom, as well as the pace of the classroom. Similarly, general education teachers defined their roles through the lens of accountability, and saw themselves as the leaders of their classrooms who were responsible for content area instruction. Special education teachers also tended to feel that 6 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS students with LD needed to be spoken for, as in special educators advocating for varied pedagogy responsive to their needs; while general educators felt this action caused students to be dependent and unprepared for the real world. Additionally, some of the special educators were frustrated at having to adapt themselves to the regular education teachers’ philosophies of classroom roles, and explained that some people feel threatened when you try to correct or change them. Effective Co-planning With the co-teaching of students with disabilities being more prominent in schools today, the co-planning between general and special educators needs to be a priority. In analyzing interview data, Moin et al. (2009) reaffirmed that in successful co-teaching cases, the co-teaching model was implemented school wide or strongly endorsed and supported by the administration. In the successful cases of administrators encouraging adoption of the coteaching model school-wide, it was reported that they demonstrated supports such as scheduling co-planning time for co-teaching pairs weekly, and organizing summer professional development seminars for both members of the co-teaching pair together. Monitoring Student Progress Many middle and high schools rely on the co-teaching model to deliver content instruction to adolescents with IEPs, particularly to prepare students for participation in the state’s high-stakes assessments (Nichols, Dowdy, & Nichols, 2010). Fontana (2005) investigated how the academic achievement of eighth graders with learning disabilities was influenced by the co-teaching model of service delivery, as compared to the resource room model of service delivery the participants had their seventh grade school year. Results indicated significant improvement in the final averages of the co-taught eighth-grade group when compared with their final averages as seventh graders, as well as an increase in selfconcept and math scores. Additionally, McDuffie et al. (2009) found no additional value was 7 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS added when peer-tutoring was implemented in co-taught classrooms, however, noted that students in co-teaching settings performed significantly better than those in non-co-teaching settings (p = .019) in identification items on a cumulative posttest measure. Magiera and Zigmond (2005) compared the instructional experiences of special education students in co-taught and non-co-taught classes in secondary schools under the routine condition of limited preparation about how to co-teach, and limited or no co-planning time for teachers. The researchers found significant differences for the targeted students with disabilities in co-taught and non-co-taught settings, in terms of general education teacher interaction and individual instruction. General education teachers spent significantly less time attending to students with disabilities when the special education teacher was present; and students with disabilities received significantly more individual instruction from the special education teacher. Their observation tool was adapted from Boudah et al. (1997) in a co-teaching study that focused on who interacted with students, the participation of students, and the type of academic or non-instructional interactions students had with co-teachers. Zigmond (2006) explored the reading and writing demands of high school social studies classes in a re-analysis of narrative notes collected in a larger co-teaching study. She found that accommodating to the skill level of students is very limiting as a long-term solution because filtering the content to be delivered ahead of time limits the role of a special education co-teacher to assist in modifying and adapting course material. For example, students may give up learning how to read and become dependent on their teacher as their primary source of information because teachers are accommodating to the reading deficiencies of their students. PKS ADD TRANSITION SENTENCE TO LEAD TO MODELS OF CO-TEACHING 8 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS Models of Co-Teaching As previously mentioned, Scruggs et al. (2007) found the “one teach, one assist” coteaching model to be the most widely used in their metasynthesis of literature on co-teaching. This approach often has the special education teacher playing a subordinate role because general educators perceive that special educators may not know the content, the general educators’ consider the classroom to be their “turf,” and there are more general education students in the classroom. Six co-teaching models are identified by Cook and Friend (1995) and Friend and Bursuck (2002). The six co-teaching models and definitions are: One Teach, One Observe: One co-teacher leads the lesson while the other co-teacher observes students. One Teach, One Drift: One co-teacher leads the lesson while the other co-teacher circulates and assists students as needed. Station Teaching: Similar to a Learning Center approach with content and students are divided between stations (or Learning Centers), and students rotate from one coteacher’s station to another. Parallel Teaching: Both co-teachers instruct the same information simultaneously with the class divided about equally to form two groups. Alternative Teaching: One co-teacher instructs a larger group while the other coteacher instructs an alternative lesson or the same lesson taught at a different level with a smaller group. Team Teaching: Both co-teachers deliver instruction interactively. Scruggs et al. (2007) found that co-teachers participating in interviews noted they used the following co-teaching models the least: parallel teaching, team teaching, alternate teaching, and station teaching. One co-teacher reported that parallel teaching did not seem to be effective because each group was distracted by the teachers’ loud voices. The researchers 9 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS pointed out that although the alternate teaching model typically occurs in the same classroom, in this study, alternate teaching featured the special education and general education coteachers instructing students in different classroom settings. Boudah et al. examined the effects of a collaborative instructional (CI) model in inclusive secondary classes, which included students with mild disabilities and low-achieving students. The baseline results indicated that co-teaching teams spent about 62% of class time involved in non-instructional activities, 19% of the time circulating to work with individual students, 9% of the time presenting content, 8% of the time mediating student learning, and 5% of time devoted to exchanging roles. However, after training in the CI Model, co-teachers devoted a greater percentage of instructional time to mediating the learning of students in their classes (22%) and exchanging instructional roles (18%). Other positive results regarding instructional actions indicated a three-percent decrease in both the percentage of time that co-teacher teams presented content (6%), and circulated to work with individual students (16%). There was also an eight-percent decrease in non-instructional activities (54%) in one class period. Kilanowski and Foote (2010) found that co-teaching is cited as the least documented model of instruction, while the implementation of one-to-one student support emerged as the most prevalent model. Gurgur and Uzuner (2010) analyzed the opinions of special and general education teachers, regarding both preparing for, and planning lessons in their coteaching approach. The educators interviewed indicated that each model of co-teaching has advantages and disadvantages so cannot be said which one is the most effective, as it changes according to the lesson taking place. The researchers also concluded that the one teach, one assist model may have been implemented as a possible solution to the lack of adequate planning problem. For example, co-teachers who have little or no co-planning time may be 10 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS deferring to the co-teaching model which seems most conducive to one teacher leading and the other following along in a less active instructional role. The Current Study Secondary special education co-teachers not only work with different content teachers, they work with teachers who have different teaching styles. Consequently, special educators can also feel like chameleons, particularly when they need to shape their instructional behaviors to fit the diverse teaching styles of the content teachers. Some of the shaping of instructional behaviors should also be occurring for general education co-teachers, because general education co-teachers likely co-teach with one special educator. There is a difference, then, for special educators who co-teach multiple subjects across a school day with multiple general education co-teachers. The purpose of this study was to elicit information from secondary special education co-teachers about their perceptions of how coteaching was being implemented by them and their general education partners. The primary research questions were: 1. When asked about specific instructional responsibilities, what do respondents believe are the responsibilities of the general educator, special educator, or both educators? 2. How do special education co-teachers rate their instructionally-related behaviors and interactions with general education co-teachers in the five domains of co-teaching relationship, pedagogy and instructional climate, parity, co-planning, and monitoring students’ progress to make changes? 3. Which models of co-teaching do special education co-teachers identify as most used to least used? 4. Do special education co-teachers who volunteer to be co-teachers rate any of the domains higher/differently than special education co-teachers who were told they would be co-teachers? 11 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS 5. Which models of co-teaching do special education co-teachers who volunteer to be co-teachers identify as most used to least used? 6. Do special education co-teachers with more experience as a co-teacher rate any of the domains higher/differently than special education co-teachers with less experience? 7. Which models of co-teaching do special education co-teachers with more experience as a co-teacher identify as most used to least used? 8. Which models of co-teaching do special education co-teachers with less experience as a co-teacher identify as most used to least used? 9. Do special education co-teachers with different amounts of professional development rate any of the domains higher/differently? 10. Which models of co-teaching do special education co-teachers with different amounts of professional development more experience as a co-teacher identify as most used to least used? 11. Do special education co-teachers with different amounts of preparation during their teacher preparation program rate any of the domains higher/differently? 12. Which models of co-teaching do special education co-teachers with different amounts of preparation during their teacher preparation program identify as most used to least used? 13. Do special education co-teachers with different amounts of preparation either via professional development and/or during their teacher preparation program rate any of the domains higher/differently? 14. Which models of co-teaching do special education co-teachers with different amounts of preparation either via professional development and/or during their teacher preparation program as identify as most used to least used? 12 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS 15. Do special education co-teachers agree or disagree that they had to overcome interpersonal challenges? 16. Do special education co-teachers agree or disagree that students perceive the coteaching team as equal? 17. Do special education co-teachers agree or disagree that they had to overcome challenges? 18. Do special education co-teachers agree or disagree that co-teaching is an effective service delivery for students with disabilities? 19. Do special education co-teachers agree or disagree that daily co-planning is not difficult to coordinate? 13 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS Method Recruitment of Participants Special educators teaching sixth, seventh, eighth, and ninth grades in four states (Virginia, Delaware, West Virginia, and Maryland) were targeted as the total population of educators from which a random selection occurred to determine recipients of the web-based survey. Twenty-five percent (or one in four) of the special educators were randomly selected to receive an electronic mail (email) message inviting them to participate in the co-teaching survey. Because we desired responses from current co-teachers, special educators who were not current co-teachers (i.e., that semester; that year) were asked to delete the email because they were not the targeted respondents. Notably, it was not possible to determine which nonrespondents were or were not currently co-teaching, which precluded determining accurate response rates. An initial email and one follow-up email inviting special education coteachers to participate in this research were sent in late May and early June of that school year. Characteristics of Participants The co-teaching participants’ characteristics are identified in detail in Table 1. Ninetyone of the special educators, who completed all or most of the survey, were secondary special education co-teachers. About half of the of the participants taught middle school grades 6-8, and the remaining half of the participants taught high school grades 9-12. Regarding the coteachers’ ages, about the same number of special educators were under 40-years-old (38.5%) as were over 51-years-old (39.6%). For gender, just over four-fifths of special educators were female, with about one-fifth male. Most co-teachers were Caucasian (81%), followed by African-American (9%). Over half of the participants had their master’s degree (63.3%), 33.3% had their bachelor’s degree, and 3.3% had educational specialist degrees. Almost all of the participants 14 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS had full certification in special education (90%), while 10% were working toward full certification. About three-fourths of the participants were also considered highly qualified according to the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) legislation requirements, the remaining teachers had not yet acquired highly qualified status or were unsure. Almost one-third of the participants were beginning teachers, with between one and five years of teaching experience. About one-quarter of the participants had six to ten years of teaching experience, almost another quarter of the participants had eleven to fifteen years of teaching experience, and the rest of the participants had over sixteen years of teaching experience. Data were also collected regarding the number of years each participant had experience as a special education co-teacher. Over half of the participants were beginning coteachers, with one to five years of co-teaching experience, a little over one quarter of the participants had six to ten years of co-teaching experience, and the rest had eleven or more years of co-teaching experience. Co-teachers identified the disability labels for students they co-taught, and the disability category that most co-teachers instructed was learning disabilities (96%). Eighty-seven percent of the students taught by the co-teachers fit the category of emotional disturbance, and 74% of the students had the disability label of autism. Demographics of Schools Characteristics of the schools where participants co-taught are identified in Table 2. Fifty-six percent of the schools were geographically located in suburban areas, 33% were in rural areas, and 11% were in urban areas. Forty-five percent of the schools had a population of less than 1,200 students, 32% had between 1,201 and 1,800 students, and 23% had more than 1,801 students. Seventy-two percent of the schools were located in the Southeast of the United States, 6% were located in the Southwest, and 22% were located in the Mideast. The survey also asked special education co-teachers about their school’s diversity. Forty-seven percent of the schools had 25% or less minority students enrolled, 31% of the 15 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS schools had between 26% to 50% minority students enrolled, and 22% of the schools had more than 51% minority students enrolled. The special education co-teachers were also queried about the socio-economic status of students at their school. Thirty-one percent of the schools had less than 25% of the students on free and reduced lunch programs, 42% of the schools had 25% to 49% of the students on free and reduced lunch programs, and 27% of the schools had more than 50% of the students on free and reduced lunch programs. Participants’ Preparation and Experiences with Co-Teaching Completed 1-9-10 AEB Years of co-teaching experience and the amount of preparation for co-planning and co-teaching are displayed in Table 3. It’s specified that just over half (58%) of the co-teachers had from one to five years of co-teaching experience. Overall, most co-teachers (86%) had ten or fewer years of co-teaching experience. In contrast, about one-fifth (21%) of the teachers had 11 or more years of teaching experience. Additionally, thirty-eight percent of the co-teachers were hired to be co-teachers, and about the same percentage (40%) was told by administrators that they would be co-teachers. Close to half (52%) of the special education co-teachers surveyed reported having less than three hours of professional development for co-planning and co-teaching, and about onefourth (26%) of the co-teachers had from one to three days. In addition, 22% of the coteachers reported having more than three days of co-teaching professional development. Regarding teacher preparation for co-teaching, 61% of the co-teachers surveyed reported having some coursework in co-planning/co-teaching. Specifically, 44% had at least one course session, and 17% of the co-teachers experienced three or more course sessions in coteaching preparation. 16 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS Co-Teaching Instrument The Co-Teacher Survey was developed by the primary investigator, with successive iterations of the instrument analyzed for content validity by administrators who supervised co-teachers, general and special education co-teachers, and university personnel who researched and published on co-teaching. The Co-Teacher Survey is a web-based survey with an opening statement that the recipients must be co-teaching that school year in order to participate in the research study. If they are not currently co-teaching, they are directed to close the survey. For recipients who are currently co-teaching, they continue with the Electronic Informed Consent as the first page of the survey. Recipients must indicate their Informed Consent before clicking to the next page of the survey. The beginning of the survey elicits information about demographic characteristics about the participants themselves, including how much preparation they have completed about co-teaching and whether they volunteered or were told they would be a co-teacher, as well as the school in which they teach. Participants also indicate from a listing of instructional tasks whether they believe the primary responsibility belongs to the general educator, the special educator, or both educators. A series of statements comprise each of the six domains of the survey: 1) Co-Teaching Relationship (CTR), which is defined on the survey as the interpersonal skills and collegial rapport that co-teachers experience. The 13 items in this domain were found highly reliable (α = .90). 2) Co-Teachers’ Pedagogy and Instructional Climate (CTPIC), which is defined on the survey as one or both of the co-teachers’ learning content and methods that improve instruction and create an effective instructional environment. This learning promotes the effective design and delivery of instructional content and behavior management 17 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS techniques as a result of working with one or more co-teachers. The 13 items in this domain were found highly reliable (α = .87). 3) Parity, which is defined on the survey as the equality that each co-teacher experiences within the co-teaching experience. Each co-teacher feels that his or her contributions are elicited, valued, and respected. Instruction is designed and implemented by both co-teachers. The 13 items in this domain were found acceptable for reliability (α = .73). When further disaggregated for true parity, general educator as lead, and special educator as lead, the corresponding Cronbach alphas were ,85, .88, and .86. 4) Effective Co-Planning (ECP), which is defined on the survey as the two educators discussing and developing, in advance of their co-teaching (excluding hallway or brief informal interactions or conversations), the way that they will co-teach the content and manage the instructional environment. The 11 items in this domain were found highly reliable (α = .90). 5) Monitoring Students’ Progress to Make Changes, which is defined on the survey as activities that co-teachers do to determine how well students are learning so that the co-teachers can provide responsive instruction. There were too few items to determine reliability for this domain. 6) Models of Co-Teaching, which is defined on the survey as co-teachers planning and implementing one of the co-teaching models initially described by Cook and Friend (1995). In this survey, we used co-teaching models, definitions, and graphics from Cook and Friend, and Friend and Bursuck (2002). The scale for this domain switched from the amount of agreement to co-teachers indicating the percentage of time they used each co-teaching model. Participants indicate whether they strongly disagree (rating of 1), disagree (rating of 2), agree (rating of 3), or strongly agree (rating of 4) with the statement. Statements 18 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS throughout are intentionally worded negatively (e.g., I have not improved my teaching through working with a teacher who has different skills than mine.) to ensure respondents are reading each statement. At varied points throughout the survey, space for open-ended queries occur so that respondents can add comments about a specific item or domain as they desire. The Co-Teaching Survey is also designed so that co-teachers who co-teach with more than one co-teacher can respond more than one time to each section of the survey which queried regarding a specific co-teaching team. This is referred to as looping (CITE NEEDED “When the same question or set of questions is asked multiple times for different options it is termed as looping. Looping allows you to dynamically "loop" through a set of questions based on responses to a multiple choice question.”). The looping option was inserted into this version of the Co-Teacher Survey because in earlier versions, special education co-teachers indicated that their responses changed based on which co-teacher they were responding for. The maximum number of times respondents could loop through a section was limited to four, so co-teachers could respond for up to four co-teaching situations (i.e., teams) with which they were currently teaching. Respondents did not identify their names at any point during the survey. However, if they wanted their name to be entered for the raffle of several iPods, they did need to provide an email address for contact information. This information was separated from their survey responses so that anonymity was maintained. Results Instructional Responsibilities Special education co-teachers noted which instructional responsibilities they believed belonged to the general educator, themselves as the special educator, or both educators. Refer to Table 4 for the listing of eleven instructional tasks and the special education coteachers’ responses for the person, or the people, that each responsibility or task belonged to. 19 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS In summary, at least 65% of participants indicated that both teachers are equally responsible for the designated classroom tasks. For all eleven tasks, “both educators” was more frequently identified (65% to 97% range) as who had the responsibility for the task. Almost all of the special education coteachers noted that the following tasks were shared by both educators: behavior expectations (93%), parent contact (93%), and working with students with disabilities (97%). Conversely, special educators were infrequently (2% to 6% range) noted as having the primary responsibility for tasks, with most tasks as both educators and, less frequently, the general educator. Additionally, lesson planning (33%) and providing accommodations and modifications to students (35%) were the highest areas that had the highest percentages with a response of “general educator” responsible for the task. Domains AEB drafted overall domain results 1-10-12 Special education co-teachers also rated their instructionally-related behaviors and interactions with general education co-teachers in the five domains of co-teaching relationship, pedagogy and instructional climate, parity, co-planning, and monitoring students’ progress to make changes. In the first domain, 90% of survey respondents identified their co-teaching relationship as being a positive experience, as displayed in Table 5. Ninety-three percent of co-teachers reported both teachers having sufficient content knowledge and proficiency with methods to improve instruction and create an effective instructional climate in the second domain. Regarding parity in the third domain, 80% of the co-teachers rated themselves as having shared roles, or an equal experience in their instructional settings. Meanwhile, 69% percent of respondents reported the general educator to have the lead role in the co-taught classroom. However, only 12% of co-teachers rated the special educator as having a primary teaching role. In the fourth domain, 76% of the respondents reported having an effective co-planning process. Finally, the results for the fifth 20 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS domain indicate that 84% of co-teachers participate in ways to monitor students’ progress to make changes. Individual statements taken from selected domains in the survey regarding the extent to which special education co-teachers are in agreement are highlighted in Table 6. The majority of special education co-teachers surveyed (94.3%) are in agreement that co-teaching is an effective service delivery for students with disabilities, and just over half (66%) agree that students perceive their co-teaching team as equal. In addition, close to half of survey participants agreed that they have not had to overcome interpersonal challenges (66%) and that daily co-planning is difficult to coordinate (57%). Survey data was analyzed to determine whether special education co-teachers who volunteer to be co-teachers rate any of the domains higher/differently than special education co-teachers who were told they would be co-teachers. Independent samples t-tests indicate that there is not a significant difference between co-teachers who did or did not volunteer for co-teaching positions in ratings of pedagogy and instructional climate, t(67)=-1.44, p = n.s.; co-teaching relationships, t(87)=-.89, p = n.s.; parity indicating shared responsibilities, t(67)=-1.16, p = n.s.; and parity indicating general educator as lead teacher, t(67)=104, p = n.s. Results indicate there is a significant difference in ratings for effective co-planning, t(66)=-2.71, p = .001, for the special educator as lead teacher, t(67)=-2.30, p = .03, and for progress monitoring, t(66)=-2.50, p = .02. Co-teachers who did not volunteer to be coteachers provided significantly lower ratings in these three areas. Means and standard deviations are reported in Table 7. Co-teaching Models AEB drafted 1-16-12 Special education co-teachers identified models of co-teaching by the most used to least used as detailed in Table 8. The co-teaching models used most frequently by co-teachers are the “one teach, one observe” and “one teach, one drift.” In contrast, the models of station 21 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS teaching, parallel teaching, alternative teaching, and team teaching were reported to be implemented the least by survey respondents. The differences between use of models of co-teachers who volunteered for coteaching positions and those who did not are identified in Table 9. Independent samples ttests indicate that there is not a significant difference between co-teachers who did or did not volunteer for their frequency of us of five of the six models of co-teaching. Some co-teachers responded for a model they used the most and the least versus providing a response for every model of co-teaching. For One Teach One Observe, the t(34)=-1.63, p = n.s.; for One Teach One Drift, the t(65)=-1.82, p = n.s.; for Station Teaching, t(60)= 1.71, p = n.s.; for Alternative Teaching, t(34)=-1.63, p = n.s.; for Team Teaching, t(63)= 7.95, p = n.s. There was a statistically significant result for Parallel Teaching, t(62)= 2.23, p = .03, indicating that co-teachers who did not volunteer used Parallel Teaching significantly more than co-teachers who did volunteer to co-teach. Discussion The NCLB regulation regarding highly qualified statues may be the reason for so many special educators having a master’s degree. . These data may be representative of the fact that recent general education graduates are entering the classroom with more knowledge of special education strategies than in the past, and are willing to co-teach in their school settings. . It makes sense that the majority of students with disabilities in co-taught classes were categorized under these 3 disabilities because they are instructed in the general education curriculum and are expected to participate in state assessments including their grade level objectives. 22 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS 23 According to Buckley (2005), teachers’ perceptions of their co-teaching roles may be the most significant factor in building and maintaining relationships. http://www2.ed.gov/about/reports/annual/osep/index.html 50 states 54.24 25.14 and D.C. (including BIA schools) Outside regular Public separ class facil < 21% Alabama 67.05 23.57 16.67 Private separ facil 21-60% 6.61 1.77 1.17 Public resid facil 1.26 0.12 0.28 0.28 0.45 Private resid Home hosp envir facil > 60% 0.51 0.54 0.34 Overall at least 65% of participants indicated that both teachers are responsible for the designated classroom tasks for each category. This data differs from previous research studies regarding parity which found that the special educators’ co-teaching role is more of an instructional assistant than an instructional equal with general education content teachers (Moin, Magiera, & Zigmond, 2009; Scruggs et al., 2007). The results of the current study suggests there has been an improvement in coteaching based on comparisons to previously completed research which indicates that general educators lead the content instruction, leaving special educators with insufficient opportunities to use their strong pedagogical skills with students who need those skills the most (McDuffie, Mastropieri, & Scruggs, 2009; Moin, Magiera, & Zigmond, 2009; Murawski, 2006). 100.0 All envir 100.0 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS References Bouck, E.C. (2007). Co-teaching…not just a textbook term: Implications for practice. Preventing School Failure, 51, 46-51. doi:10.3200/PSFL.51.2.46-51 Boudah, D.J., Schumacher J. B., & Deshler, D. D. (1997). Collaborative instruction: Is it an effective option for inclusion in secondary classrooms? Learning Disability Quarterly, 20, 293-316.doi:10.2307/1511227 Buckley, C.Y. (2005). Establishing and maintaining collaborative relationships between regular education and special education teachers in middle school social studies inclusive classrooms. Advances in Learning and Behavioral Disabilities, 18, 161– 208.doi:10.1016%2FS0735-004X%2805%2918008-2 Cook, L., & Friend, M. (1995). Co-teaching: Guidelines for effective practice. Focus on Exceptional Children, 28(2), 1-12. Friend, M., & Bursuck, W.D. (2002). Including students with special needs: A practical guide for classroom teachers. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Gurgur, H., & Uzner, Y. (2010). A phenomenological analysis of the views on co-teaching applications in the inclusive classroom. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 10, 311-331. Hang, Q., & Rabren, K. (2009). An examination of co-teaching: Perspectives and efficacy indicators. Remedial and Special Education, 30, 259-268. Harbort, G., Gunter, P. L., Hull, K., Brown, Q., Venn, M. L., Wiley, L. P. & Wiley, E. W. (2007). Behaviors of teacher in co-taught classes in a secondary school. Teacher Education and Special Education, 30(1), 13-23. doi:10.1177/088840640703000102 Isherwood, R. S., Barger-Anderson, R. (2008). Factors affecting the adoption of co-teaching models in inclusive classrooms: One school’s journey from mainstreaming to inclusion. Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research, 2, 121-128. 24 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS Kilanowski-Press, L., Foote, C. J., Rinaldo, V. J. (2010). Inclusion classrooms and teachers: A survey of current practices. International Journal of Special Education, 25(3), 4356. Magiera, K., & Zigmond, N. (2005). Co-teaching in middle school classrooms under routine conditions: Does the instructional experience differ for students with disabilities in co-taught and solo-taught classes? Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 20, 7985. McDuffie, K.A., Mastropieri, M.A., & Scruggs, T. (2009). Differential effects of peer tutoring in co-taught and non-co-taught classes: Results for content learning and student-teacher interactions. Exceptional Children, 75, 493-510. Moin, L.J., Magiera, K., & Zigmond, N. (2009). Instructional activities and group work in the US inclusive high school co-taught science class. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 7, 677-697. doi:10.1007/s10763-008-9133-z Murawski, W.W. (2006). Student outcomes in co-taught English classes: How can we improve? Reading and Writing Quarterly, 22, 227-247. doi:10.1080/10573560500455703 Nichols, J., Dowdy, A., & Nichols, C. (2010). Co-teaching: An educational promise for children with disabilities or a quick fix to meet the mandates of No Child Left Behind? Education, 130, 647-651. Scheeler, M. C., Congdon, M., & Stansberry, S. (2010). Providing immediate feedback to co-teachers through bug-in-ear technology: An effective method of peer coaching in inclusion classrooms. Teacher Education and Special Education, 33(1), 83-96. doi: 10.1177/0888406409357013 25 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS Scruggs, T.E., Mastropieri, M.A., & McDuffie, K. A. (2007). Co-teaching in inclusive classrooms: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Exceptional Children, 73, 392416. Zigmond, N. (2006). Reading and writing in co-taught secondary school social studies classrooms: A reality check. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 22, 249-268. 26 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS 27 Table 1 Demographics of Participants Grades Taught Age Gender Ethnicity Education Level Certification in Special Education 6th to 8th grades 44% 9th to 12th grades 59% 20-30 years 17.6% 31-40 years 20.9% 41-50 years 22% 51+ years 39.6% Male 19% Female 81% African-American 9% Asian-American 1% Caucasian 81% Hispanic (includes Latino) 2% Pacific Islander 1% Bi- or multi-racial 3% No response 3% Bachelor's Degree 33.3% Master's Degree 63.3% Educational Specialist 3.3% Fully certified 90% Working toward full certification 10% Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS Highly Qualified Years Teaching 28 Yes 78% No 15% Unsure 6% 1-5 years 28% 6-10 years 23% 11-15 years 19% 16-20 years 11% 21-25 years 7% 26+ years 13% Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS 29 Table 2 Demographics of Schools Where Participants Co-Taught School Size of School Location of School School’s "Minority Enrollment" Students on Free or Reduced Lunch Rural 33% Suburban 56% Urban 11% Less than 600 students 12% 601 to 1,200 students 33% 1,201 to 1800 students 32% 1,801+ students 23% Southeast 72% Southwest 6% Mideast 22% Less than 5 percent 9% 5 to 25 percent 39% 26 to 50 percent 31% 51 to 75 percent 20% 76 to 95 percent 1% 96 percent or more 1% Less than 25 percent 31% 25 to 49 percent 42% 50 to 74 percent 21% 75 percent or more 7% Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS 30 Table 3 Co-Teaching Experience and Preparation for Co-planning and Co-teaching Years Co-Teaching 1-5 years 58% 6-10 years How Acquired Position Amount of Professional Development 28% 11-15 years 9% 16-20 years 2% 21-25 years 2% 26+ years 1% Approached by administrator 12% Hired to be a co-teacher 38% Independently volunteered 10% Told by administration 40% None 1 to 3 hours 14.3% 37.4% 3.35 3.31 1 day or less 14.3% 1 to 3 days 12.1% 3.1 More than 3 days 22% 2.7 Teacher Preparation for No portion of a course 39% 1.9 Co-planning/Co-teaching At least one course 34% 2.87 At least 3 course sessions 6% 3.04 1 course 10% Several courses/sessions 11% Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS 31 Table 4 Classroom Responsibilities Task General Special Both Educator Educator Educators Knowledge of Instructional Content 16% - 84% Behavior Expectations for Students 1% 6% 93% Daily Lesson Planning 35% - 65% Long Term Planning 33% - 67% Instructional Routines 16% 2% 83% Organizational Routines 19% 2% 79% Providing Accommodations 33% - 67% Student Evaluation (e.g., Grading) 22% 2% 76% Material(s) Preparation for Lessons 25% - 75% Parent Contact 4% 3% 93% Working with Students with Disabilities 17% - 97% and Modifications to Students Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS Table 5 (AEB added draft table 1-12-12) Overall Domain Averages RAW Domain 1 2 3 4 mode Co-Teaching Relationship Pedagogy and Instructional Climate Parity Shared General Educator Lead Special Educator Lead 3.3 6.7 35.5 54.5 4.00 3.00 2.9 4.3 51.4 41.4 4.3 15.7 41.4 38.6 3.00 10.0 31.4 40.0 28.5 3.00 20.0 68.6 5.8 5.7 2.00 Effective CoPlanning 5.6 16.9 62.0 15.5 Effective Progress Monitoring 4.3 11.6 59.4 24.6 3.00 6.00 32 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS 33 Table 6 (AEB added draft table 1-12-12) Individual Statements from the Survey ___________________________________________________________________________ Do special education co-teachers 1 2 3 4 Raw Mode agree or disagree that: They had to overcome 23.9% 42% 20.5% 13.6% 2.00 interpersonal challenges. Students perceive the co-teaching team as equal. 7.9% 23.6% 24.7% 43.8% 4.00 Co-teaching is an effective service delivery for students with disabilities. 2.9% 2.9% 40% 54.3% 4.00 Daily co-planning is not 24.3% 32.9% 30% 12.9% 2.00 difficult to coordinate. ___________________________________________________________________________ Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS 34 Table 7 (new-PKS) Domain Rating Differences between Non-Volunteers and Volunteers for Co-Teaching Positions Domain 1: Co-Teaching Relationship Domain 2: Pedagogy and Instructional Climate Mean Std. Deviation Non-Volunteers 3.26 0.92 Volunteers 3.41 0.63 Non-Volunteers 3.16 0.90 Volunteers 3.41 0.54 Non-Volunteers 2.96 0.95 Volunteers 3.20 0.74 Non-Volunteers 2.66 0.77 Volunteers 2.64 0.97 Non-Volunteers 1.64* 0.47 Volunteers 2.03 0.78 Non-Volunteers 2.56* 0.82 Volunteers 3.03 0.63 2.76* 0.83 3.21 0.64 Domain 3: Parity Shared General Educator Lead Special Educator Lead Domain 4: Effective CoPlanning Domain 5: Effective Progress Non-Volunteers Monitoring Volunteers *p < .05 am not sure I’ve got these right? Anne – double check you’re not finding errors. I always need another set of eyes after me (and vice versa!). The table needs to be checked for APA. Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS 35 Table 8 (AEB added draft table 1-12-12) Frequency Models of Co-teaching Used by Special Education Co-teachers Co-Teaching Model 0% 14% 15% 34% 35% 49% 50% 74% One Teach, One Observe 75% 89% 90% 100% 27.8%? 72.2% RAW mode 1.00 One Teach, One Drift 35.3 14.7 20.6 8.8 14.7 5.9 Station Teaching 1.6 1.6 6.3 11.1 23.8 55.6 6.00 Parallel Teaching 6.2 4.6 7.7 4.6 16.9 60 6.00 Alternative Teaching 1.5 3.1 12.3 4.6 15.4 63.1 Team Teaching 13.6 24.2 12.1 9.1 15.2 25.8 1.00 6.00 6.00 Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS 36 Table 9 (new-PKS) Models of Co-Teaching Differences between Non-Volunteers and Volunteers for CoTeaching Positions One Teach One Observe One Teach One Drift Station Teaching Parallel Teaching Alternative Teaching Team Teaching Mean Std. Deviation Non-Volunteers 3.16 0.18 Volunteers 3.41 0.08 Non-Volunteers 2.56 0.16 Volunteers 3.03 0.09 Non-Volunteers 2.76 0.17 Volunteers 3.21 0.10 Non-Volunteers 3.26* 0.15 Volunteers 3.41 0.09 Non-Volunteers 2.96 0.19 Volunteers 3.20 0.11 Non-Volunteers 2.66 0.15 Volunteers 2.64 0.15 *p < .05 am not sure I’ve got these right? Anne – double check you’re not finding errors... ? The table needs to be checked for APA. Draft 1.16.12 SECONDARY SPECIAL EDUCATION CO-TEACHERS 4.2 no m 5.2 no n 6.2afim 6.2bcdeg 6.2hjkl 7.2a,c,d,e,f,g,k,l,m,n,o 8.2a,b,d Co-Teaching Relationships Good? Effective pedagogy and instructional climate Parity exists; shared responsibilities. Parity is general educator as lead. Parity is special educator as lead. Effective co-planning Students' progress monitored for changes 37 Median 3.35 3.31 3.1 2.7 1.9 2.87 3.04 Not much Some preparation on Lots of preparation preparation on co- co-teaching on co-teaching teaching Co-Teaching Relationships Good? Effective pedagogy and instructional climate Any statistically significant differences?