Elements of Socratic Seminars Socrates believed that enabling

advertisement

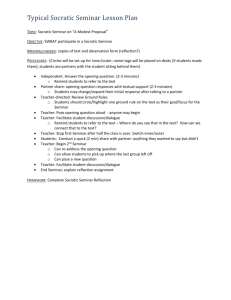

Elements of Socratic Seminars Socrates believed that enabling students to think for themselves was more important than filling their heads with “right answers.” In a Socratic Seminar, participants seek deeper understanding of complex ideas through rigorously thoughtful dialogue, rather than by memorizing bits of information or meeting arbitrary demands for “coverage.” A Socratic Seminar fosters active learning as participants explore and evaluate the ideas, issues, and values in a particular text. A good seminar consists of four interdependent elements: (1) the text being considered, (2) the questions raised, (3) the seminar leader, and (4) the participants. A closer look at each of these elements helps explain the unique character of a Socratic Seminar. The Text Socratic Seminar texts are chosen for their richness in ideas, issues, and values, and their ability to stimulate extended, thoughtful dialogue. A seminar text can be drawn from readings in literature, history, science, math, health, and philosophy or from works of art or music. A good text raises important questions in the participants’ minds, questions for which there are no right or wrong answers. At the end of a successful Socratic Seminar, participants often leave with more questions than they brought with them. The Question A Socratic Seminar opens with a question either posed by the leader or solicited from participants as they acquire more experience in seminars. An opening question has no right answer; instead, it reflects a genuine curiosity on the part of the questioner. A good opening question leads participants back to the text as they speculate, evaluate, define, and clarify the issues involved. Responses to the opening question generate new questions from the leader and participants, leading to new responses. In this way, the line of inquiry in a Socratic Seminar evolves on the spot rather than being pre-determined by the leader. The Leader In a Socratic Seminar, the leader plays a dual role as leader and participant. The seminar leader consciously demonstrates habits of mind that lead to a thoughtful exploration of the ideas in the text by keeping the discussion focused on the text, asking follow-up questions, helping participants clarify their positions when arguments become confused, and involving reluctant participants while restraining their more vocal peers. As a seminar participant, the leader actively engages in the group’s exploration of the text. To do this effectively, the leader must know the text well enough to anticipate varied interpretations and recognize important possibilities in each. The Participants In Socratic Seminar, participants share with the leader the responsibility for the quality of the seminar. Good seminars occur when participants study the text closely in advance, listen actively, share their ideas and questions in response to the ideas and questions of others, and search for evidence in the text to support their ideas. Participants acquire good seminar behaviors through participating in seminars and reflecting on them afterward. After each seminar, the leader and participants discuss the experience and identify ways of improving the next seminar. Before each new seminar, the leader also offers coaching and practice in specific habits of mind that improve reading, thinking, and discussing. Seminar Guidelines and Grading Seminar participants MUST: Be prepared. Listen carefully, actively and respectfully. 1 Speak clearly and concisely, taking time to think before you speak. (Make sure to review the “seminar comment types” on the back side of this sheet) Discuss the text, not each other’s opinions. Seminar participants SHOULD: Dialogue with fellow participants, not with the leader. Invite quiet participants to speak, but don’t pressure them. 2 To ensure this happens, you should either address the previous speaker or offer a reason for changing the subject. If you are called upon and have nothing to say, the appropriate response is some variation of “I’m not sure what I think about that, but please come back to me.” 1 2 Ask good questions and for clarification when confused. Help fellow participants clarify questions and responses. Give evidence and examples to support your responses. Direct the discussion back to the original topic if/when the conversation wanders 3 Silence is part of a seminar, too. People are thinking (or appear to be thinking). “Penalty” Cards Yellow card: If you receive two yellow cards, you will receive an “F” for the seminar and you not be allowed to participate in the remainder. Talking while others are talking (different from two people starting to talk at the same time) Interrupting (even unintentionally) Calling attention to yourself/immaturity (visible or audible disappointment when you don’t get something you want; general goofiness, such as dancing in your seat, making faces/noises, etc.) Not listening/staring off into space/”playing” with your stuff/appearing uninvolved Red card: If you receive one red card, you will receive a “0” for the seminar and you will not be allowed to participate in the remainder. Rudeness/aggression Doing anything with your phone Blue card: If you receive this card, you will spend the next five minutes listening instead of talking. You may resume talking at the time written on the card. Time for you to listen. A B C D F 0 3 Adheres to seminar “musts.” Exhibits an understanding of the text. Provides insight on a variety of issues. Makes specific references to text quotations or pages in support of point. Adheres to seminar “musts.” Exhibits an understanding of the text. Provides insight on a variety of issues. Makes general references to text. Adheres to seminar “musts.” Exhibits an understanding of the text. Shares one or two meaningful comments. Adheres to seminar “musts.” Exhibits an understanding of the text. Comments are relevant but lacking in insight or understanding. Adheres to seminar “musts.” Fails to contribute in a meaningful way (fails to speak, only restates others’ ideas, etc.). Fails to adhere to seminar “musts.” Stick to the point currently under discussion; makes notes about ideas you may want to return to Socratic Seminar Comment Types – The Good and Bad Sample Prompt: “Not rounding off, but opening out.” Comment upon the way the authors deal with the ending in relation to the whole. In-Depth/Analytical Comment: where you give an in-depth response to the question. This may be followed by a text reference to support the comment. “Erich Maria Remarque ‘rounded off’ his novel by presenting Paul as being at peace with death in the closing paragraph, thus closing off his internal conflict.” Piggyback: where you agree with and expand on what a peer says. “I can agree with that because apart from being peaceful, Paul seems relieved about dying because he knows he can’t go back and be the same person he was before the war.” Text Reference: where you read a quote from the text either in support of your own comment or that of another participant. This might be followed up by an in-depth comment of your own. (Specific references are better than general references.) Specific: “On page 172, when Paul is standing in his room during leave, he thinks, ‘A terrible feeling of foreignness suddenly arises up in me. I cannot find my way back, I am shut out though I entreat earnestly and put forth all my strength.’” or bring the conversation back on course when it goes off topic too far. “Do you think that…? Is it possible that….? Does anyone feel that…? I was wondering if…” “Is it possible that the book is opened out due to the commentary on the soldier’s role? The conflict is resolved only because Paul dies – suggesting that is the only decent fate of a soldier who has seen and done such terrible things? Isn’t Remarque making us open out to analyzing wars in general?” Connection: where you relate the book to another book/story/movie/song, etc. “This is like Don Quixote in that the only way the main characters were able to preserve themselves was death because society wanted them to operate in a different way from the way they saw it.” Clarification Statement: where you politely correct someone who is misinformed. These are important in seminars because they help us to stay on track (and keep everyone “on the same page.”) Restatement: where you rephrase another’s idea without contributing anything new. (see in-depth or piggyback above) “Yes, he is calm when he dies like he is at peace with being able to die.” General: “When Paul goes home, he feels like a stranger in his home.” Unsubstantiated Response: where you make a generalized comment that has no supporting evidence. Request for Clarification: where you follow up a comment by a peer with a question asking for more information or a better understanding of their comment. “Do you mean…? Are you saying…” What do you mean by…” Paul died because he was poisoned. (Though interesting, there is no textual support for this theory.) Off-Topic Response: where you are off topic. “Do you mean that the novel is rounded off instead of opened out because of Paul’s internal conflict being seemingly resolved?” I think Paul liked cheese. (Perhaps he did, but that has no relevance to the topic.) Question: where you ask a related question or ask a peer a question designed to stimulate the conversation, develop a new avenue not yet explored, Grandstanding/Verbose Response: where you monopolize class discussion, speaking protractedly and bombastically with no regard to other participants or to relevancy to the discussion Follow-up questions genuinely refer to something that has been said or referenced. They can arise at any point during the dialogue; they are designed to further clarify or investigate an idea or perspective. Why do you say that? What do you mean by ___? Where do you find support for that in the text? ___, tell me more about (your last comment). Is this what the author intended? How would you explain in your own words what (another student) said? What would change your mind? Who is in the position to know if that is so? Why did you say “they?” What view would be in opposition to what you are saying? Techniques for Clarifying and Expanding Why do you say that? What do you mean by that word? What is a different way of saying that? What led you to that conclusion? Point to a word. What does that word mean? What would be an example? How does that relate with what you said about ___? Refer to a specific word in the text. How does that fit? Have them defend their position. Are you saying that ___? Could you rephrase that? What part don’t you get? Could you put that in your own words? How is your idea related to ___? Could you also be saying that___? Do you mean ___? I find it curious that___? What in the text supports your idea? What connections can you make with ___? Can you add something to___? How do you resolve ___? Who can tell me about ___? Think about ___. What are your thoughts? What do you understand up to the part you don’t understand? By what reasoning did you come to that conclusion? What would you say to someone who said ___? Are the reasons adequate? Why? What led you to that belief? How does that apply to this case? o o slave or servant -How are they different? How do you support that from the text? If you think they are wrong in their use of a word: o Why did you use that particular word? o Is that the author's intent? o Use a similar word (i.e. servant/employee); does it fit? If they are rattling on, slow them down with: o I don't quite follow you. o Why? o Do you say ___ (use a specific word)? If they are puzzled, ask what puzzles them. o Use an example to illustrate the polar positions. o Use yes/no questions. Involve other students in a response: o What do you think about ? o Do you agree with that? When an answer is muddled: o Look for the reason, ask about it. o Repeat the point to the student. o Use the basic concept again in a question.