The financial market remains a fertile battleground in the turf war

advertisement

Preliminary draft

Career Mobility in the Embedded Market

How Workers Find Jobs in the Japanese Financial Sector

Hiroshi Ono

Texas A&M University

March 2012

ABSTRACT

This project studies how macro-level global forces are shaping the behavior of firms and of individuals in the

Japanese financial sector, with particular focus on the increasing influence of foreign firms. These firms bring with

them employment practices that are more market-driven and less socially embedded compared to the Japanese status

quo. The co-existence of the foreign and the domestic in the Japanese labor market provides a fascinating test bed to

examine how local firms adapt to global pressures, and how workers navigate the changing institutional

environment. I employ mixed methods approach using in-depth interviews and two separate datasets of finance

professionals in Japan. My analysis reveals clearly demarcated patterns of career mobility. There is considerably

higher mobility in the foreign firms compared to their domestic counterparts. Mobility between the two sectors is

frequent, but it is predominantly a one-way transition from domestic to foreign. But I also find signs that mobility in

the foreign firms is constrained by local norms and conventions. The labor market does not operate in a vacuum

but is shaped by larger social forces.

* Direct correspondences to Hiroshi Ono, Texas A&M University, Department of Sociology, College Station, TX

77843-4351, USA.

INTRODUCTION

Scholars in organizations and human resources have long studied the question of why

some workers are more mobile than others. Research in this field has been profoundly

influenced by the sociological concept of embeddedness (Block 1990; Granovetter 1985), i.e. the

idea that organizations are embedded in their institutional environments. Their boundaries are

porous, and organizations are continuously shaped by what takes place outside of their borders

(Scott 2002). Workers in turn are embedded in the organizations that they work for, as well as

by the larger social and cultural framework that they are situated in. Workers are not

autonomous and they do not act in isolation. Their actions are determined and constrained by the

institutional context, by ongoing social relations, and by the behavior and expectations of others.

Complications arise when we compare turnover rates across cultures because we

confound different levels of analysis (Friedland and Alford 1991). For example, an observation

that turnover is lower in Japan than in the U.S. raises the crucial empirical question in

organizational analysis: Is it organizational culture or national culture that is driving the

differences in turnover? Can we conclude that Japanese workers are more “loyal” than are

American workers based on cross-country comparisons?

In this paper, I examine how organizational attributes and national culture affect career

mobility. I choose Japan as a test bed for empirical analysis. The Japanese labor market is de

facto characterized by low turnover and this makes it easier to observe deviations from this norm.

In this study, organizations are separated into two distinct types – the foreign and the domestic –

according to the foreign ownership structure of the firm.

My work is driven by the core hypothesis that loyalty is endogenous. I argue that the

high-commitment culture commonly associated with the Japanese workforce is not a unique

Japanese quality as suggested by some cultural scholars (e.g. Abegglen 1958), but an outcome of

the normative environment of the Japanese firm. I employ a unique research design which

clearly delineates the levels of embeddedness (Dobbin 1994) in organizational analysis. The

study contributes to our understanding of how organizational processes affect individual career

outcomes.

BACKGROUND

In Japan, the labor market functions under norms and institutions that value loyalty and

trust. There is an implicit understanding between workers and employers that their relationship

will be long-lasting, and that benefits over the long-run will override short-term interests (Ono &

Rebick 2003). Workers who breach this implicit contract and switch jobs are viewed as “social

defects,” and are penalized for their actions through lower pay.

Along with globalization, a new labor market has emerged in the country alongside its

Japanese counterpart. This is the market for foreign-owned firms. In recent years, we are

witnessing an increasing pattern of highly-skilled professionals who seek work in the foreign

firms in Japan.

The labor market for foreign firms represents the extreme opposite of the Japanese status

quo. It is deeply rooted in an Anglo-American home base, and operates more closely along

market principles dictated by quantity and price signals. There is more fluidity and less loyalty.

Workers switch jobs in response to higher pay. Employers dismiss workers when they are not

needed or when they underperform. In short, workers act like free agents, and firms prioritize

short-term profits in place of long-term relations.

In a country that features one of the lowest turnover rates in the world, the workers in the

foreign-owned firms stand out for their seemingly unrestrained pattern of interfirm mobility.

Some workers in the more traditional Japanese settings envy the greater independence and higher

pay, and yet others feel disdain for their money-motivated and short-sighted values.

Who are these free agents? What motivates them to move? What are the consequences

for defecting from the status quo? How do foreign firms attract workers in a labor market where

loyalty and long-term employment remain the norm? Comparing domestic versus foreign

highlights underlying differences between the market versus culture, formal versus informal, and

economic versus social.

MARKET OVERVIEW

The current study focuses on the finance sector in Japan. The Tokyo Stock Exchange is

the third largest exchange in the world by market value. Japan’s financial sector is a truly global

operation. The leading brokerage firms from around the world are represented there. Among the

workers in foreign firms, 68 percent are employed by the U.S. brokerage firms (JETRO 2004).

We therefore designate the U.S. firm as a close approximation and benchmark for the foreign

firm hereafter.

2

There are important substantive reasons for examining the finance sector. The financial

market epitomizes the advanced capitalist system. Financial products are exchanged, often

amongst anonymous buyers and sellers, over a market interface where transactions are conducted

instantaneously based primarily on prices and quantity. As Podolny (2005) explains: “Few if

any sectors contain markets that better conform to assumptions associated with the economic

model of perfect competition – specifically, the profit maximization of firms, the utility

maximization of individuals, and perfect information about the opportunities for exchange.”

Based on the market-dominated view of the financial sector, it is tempting to extrapolate

that the labor market for finance professionals also resembles a market with perfect information

and anonymous short-term trade. However, in the case of Japan, the labor market in finance is

actually well-sheltered from the pure market forces. The internal labor market is well-developed

in the finance sector, and accordingly, there is lower turnover than the private sector average. In

2006, over 60 percent of workers in finance were employed in large firms (greater than 1000

employees), and 43 percent were estimated to be covered by lifetime employment (Ministry of

Health, Labor and Welfare statistics); these numbers were18 percent and 21 percent, respectively,

for all industries in the private sector.1

The market for foreign firms in Japan

The human resource (HR) practices differ strikingly between domestic and foreign firms.

First, domestic firms conform to the internal labor market setup by recruiting larger numbers of

new graduate hires relative to mid-career hires.2 The new graduates enter the organization at the

bottom, and rise through the ranks after receiving extensive training from the firm. There is an

opposite pattern in the foreign firm, with greater numbers of mid-career hires compared to new

graduates. In fact, some foreign firms rely exclusively on midcareer recruiting of managers and

specialists (Robinson 2003). This hiring pattern suggests that the port of entry in the foreign

firms is open at all levels of the organization.

If the modus operandi of Japanese corporations is implicit and long-term, the counterpart

for the foreign firms is explicit and short-term. In place of a reward structure where wages are

determined by seniority and service to the firm, compensation in the foreign firm is tied more

closely to the workers’ performance. Foreign firms are less likely to support lifetime

employment, and more likely to use merit pay instead of seniority pay (JILPT 2005). They also

3

are more likely to use the annual salary system, where terms and conditions of pay are negotiated

on an annual basis. Wages are thus determined more by the worker’s marginal product, and less

by non-market attributes such as loyalty and commitment.

THE SETTING

We begin our theoretical groundwork by laying out the relationship between marketness

and employment duration. Following Block (1990), we define marketness as the extent to which

prices dictate economic transactions. Movement toward low marketness implies that nonprice

considerations take on greater importance in the transactions. In exchange theory (Blau 1964),

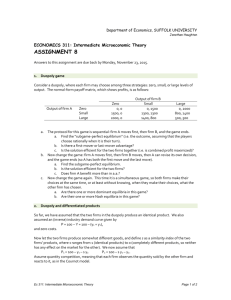

points D and F in Figure 1 indicate the ideal types representing the opposite positions of social

versus economic exchange. Economic exchange assumes that individuals are motivated

primarily by prices and quantity. Every transaction has a price, and individuals maximize utility

through cost-benefit calculations. Social influences are seen as something that disturbs

economic action (Block 1990). Under economic exchange, terms and conditions of employment

are documented explicitly. Job functions are clearly defined. Under high marketness, there is

little room for ambiguities. Workers who compete under high marketness know their market

price.

FIGURE 1 HERE

Social exchange is the status quo of the Japanese employment relationship (Murakami

and Rohlen 1992; Ono 2007). Under social exchange, workers may be motivated by prices, but

their actions are likewise influenced, and in many cases constrained by their more intimate

relationships with their employers. Lifetime employment – one of the main pillars of the

Japanese employment system – is not an explicit contract, but an implicit agreement formed

between workers and employers with the expectation that the relationship will be long-lasting

(Moriguchi and Ono 2006). Lifetime employment is thus a prime example of social exchange,

and occupies point D in Figure 1.

The intimacy of the employment relationship presumes closure, where favors are

exchanged on a daily basis. This closure fosters trust. Employers are then able to invest in the

workers, and the workers reciprocate by committing their utmost loyalty. The closure further

4

enables workers to build human capital and social capital within the firm. Much of this capital is

specific to the firm, and thus will be lost once the relationship is breached; it cannot be easily

codified or transmitted, and it cannot be quantified or priced. Workers who are employed in

these firms are not fully aware of their market worth.

Institutional complementarities

The Japanese employment system is best understood as a system of interdependent and

complementary institutions (Aoki 2001). The crucial parts that comprise the Japanese

employment system include extensive training, seniority based wages, internal promotion, job

rotation, and job security, among others. These parts are complementary to one another to the

extent that “the marginal returns from using one practice increase with the usage of another

practice” (Moriguchi and Ono 2006: 154). The cluster of these interdependent HR practices

constitutes a self-enforcing equilibrium, an outcome of which is a low-turnover model of

employment, characterized by high trust between workers and employers. If any of the parts is

removed or altered, the equilibrium is disturbed and the model becomes unstable.

The cluster analogy does not apply to the foreign firms, as there are few institutional

complementarities. HR practices are less interdependent, and there is no kernel that holds them

together, thus resulting in a model of high turnover and low trust. In this system, loyalty does

not pay, and is in fact, irrational.

In Figure 1, the domestic firm is positioned at D, and the foreign firms at F. There are

several reasons why foreign firms occupy this position. First, the majority of workers in foreign

firms are employed by U.S. firms, as previously discussed. Since the U.S. has one of the highest

labor turnover in the world, and Japan the lowest (Ono 2010), the contrast between the domestic

versus the foreign constitutes the extremes. The second reason, which is related to the first,

concerns the distinction in corporate governance. Japanese management is characterized by the

stakeholder model, which prioritizes long-term gains over short-term profits, and looks after the

well-being of their workers and other stakeholders (Jacoby 2005). Anglo-American firms, on the

other hand, uphold the shareholder model of governance, and operate under different conceptions

of legitimacy. Their management style is driven more by maximizing shareholder value, and

does not uphold the long-term approach that is common in Japanese management. With respect

to lifetime employment, Ahmadjian and Robinson (2001) explain that the practice may be

5

deemed legitimate among Japanese investors, but it is less so among U.S. and European

investors who demand immediate attention to shareholder value. This view is consistent with the

survey results which show that foreign firms are less likely to support lifetime employment than

are domestic firms (as discussed earlier).

Third, by default, foreign firms that set up their business operations overseas face a

latecomer disadvantage arising from differences in local customs, language, and institutions

(Fukao and Ito 2003). These firms do not have the luxury of time. Overcoming the latecomer

disadvantage places these firms in high-pressure situations where they are expected to produce

immediate results, so that they can catch up to the local competition. These three factors

combined push the foreign firms away from D and toward F in Figure 1.

Organizations and their environments

A key insight from institutional analysis is that what takes place within organizations is

affected by what takes place outside of it. For example, Scott et al (1994) explains:

(T)he visible structures and routines that make up organizations are direct reflections and effects of rules and

structures built into (or institutionalized within) wider environments. Organizations reflect patterns or templates

established in a wider system. (p.2)

Organizations are “open systems” (Scott 2002) which continuously interact and respond to

outside forces. Organizations and their behaviors are best understood by considering the specific

institutional environment that they are situated in.

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between organizations and their environments

intervened by national culture. Here the vertical dimension shows the marketness of the

organization, and the horizontal shows the marketness of the environment. Firm L represents the

U.S. firm in the U.S. which is a high marketness firm in a high marketness environment. On the

opposite end is firm M which is the status quo in Japan – a low-marketness firm in a low

marketness environment. Indeed, Jacoby (2005) coined the expression “the embedded

corporation” to describe the socially embedded nature of the Japanese firm. In the current

typology, the “embedded corporation” is embedded in a two dimensional schema.

Now consider the concrete example of an American investment bank such as Goldman

Sachs that enters the Japanese financial sector. This represents firm K, which is a high

6

marketness firm operating in a low-marketness environment. Their competitive environment

consists of the key Japanese (or domestic) brokerage firms such as Nomura Securities and Daiwa

Securities. Although these domestic firms may not have a full-blown lifetime employment

system in place, they still maintain an internal labor market setup with extensive job training and

considerable job security. Indeed, their organizational blueprint (Baron et al 2001) stands at

opposite ends in comparison to the U.S. brokerage firms. The Japanese financial sector thus

showcases a population of two vastly contrasting organizational forms – the highly market

driven foreign firm and the highly embedded domestic firm. It is in essence a market where the

economic meets the social.

A strategic decision for the American firm is whether to import their HR strategies with

them, or to adopt an organizational blueprint that better conforms to local labor market norms

and institutions. In other words, does firm K converge in the direction of firm M, or do they

maintain their core identity as firm L? This is a crucial decision that affects all HR operations,

including recruiting, training, compensation, retaining, and dismissal. Likewise, as the foreign

firms increase their presence in the local labor market, does firm M maintain their status quo or

do they converge towards firm K to remain competitive?

MODELS OF JOB TURNOVER

Internal labor market and human capital formation

Job turnover in Japan is remarkably low compared to the other industrialized economies

(Ono 2005). Much of this is due to the strong internal labor market setup that emphasizes job

training, job security, internal promotion, and fringe benefits (Doeringer and Piore 1971). From

the viewpoint of human capital theory, extensive on-the-job training is associated with low job

mobility, because workers accumulate skills that are specific to the firm. In fact, two of the top

reasons that workers do not change jobs in Japan are because they fear that their skills cannot be

transferred across firms, and because they will lose their returns to seniority (Ono and Rebick

2003). The longer a worker remains with the firm, the more embedded her skills become, and

the more costly it becomes to change firms. Maintaining mobility is synonymous with

avoiding specificity (Hirsch 1987).

If workers do not receive training, they do not acquire firm-specific skills. They are free

agents in the sense that they do not have any attachment to the firm beyond contractual

7

provisions. They have not invested in the firm, and the firm has not invested in them. Job

mobility is costless; there is no wage loss if they relocate to another firm. For free agents, there

is no time dimension. Their level of attachment is independent of the time they spend with the

firm. Free agents are better endowed with general human capital, or skills that are portable

across firm boundaries. Because it is easier to put a price on general skills than it is on firmspecific skills, free agents have a better sense of their market worth.

Features of the internal labor market depart from the spot-market conditions, and are

closer to the position of low marketness as depicted in Figure 1. The spot-market presupposes an

organizational setup where the ports of entry are open at all levels of the hierarchy. Workers can

be replaced by other workers as long as the incoming offer a more competitive price than the

incumbents. The internal labor market is less open because new recruits can only enter at the

bottom. By creating a market within a firm, the internal labor market shelters workers from the

brunt of business cycle fluctuations and the market volatility that accompanies it. Employers use

internal promotion to induce worker commitment, which in turn lowers overall turnover.

The movement from D to F implies a shift from firm-specific to general skills, and from

high-attachment to low-attachment. Workers that move from domestic to foreign firms

relinquish their job security, because they have left the internal labor market setup, and are no

longer insulated from external market forces. But they receive higher pay in return. This is

intuitively straightforward. The movement towards low job security involves higher risk for the

worker. Thus, difference in wages is essentially a risk premium. Alternatively, from the

perspective of workers in domestic firms, they pay an “insurance” to shield them against the risk

of low employment security. Put another way, it is inconceivable, if not irrational, that a worker

would voluntarily move to a position that carries with it higher risk but lower pay. The foreign

firm wage premium has been documented extensively in empirical studies (Ahmadjian and

Robinson 2001; Fukao and Ito 2003; Ono 2007; Ono and Odaki 2011), and we take this as given.

8

Social capital and job matching

The analysis of how workers are matched to jobs is one of the key contributions of

sociologists, and an area much neglected by the economic approach. Under the neoclassical

framework, employers have perfect information about who is looking for jobs, and how

productive they are; workers in turn know which firms are looking to fill job vacancies, and they

know their exact market worth. Job matching is costless because workers and employers are

matched to each other instantaneously in a perfectly operating market. In reality, there are

considerable transaction costs to job matching. Employers must invest time and resources

searching for the right candidate through a number of channels, e.g. posting advertisements,

hiring headhunters, spreading information by word of mouth, etc.

Social capital theory asserts that job matching can be facilitated by taking advantage of

the resources that are embedded in social relations. The quantity, quality and value of the social

capital vary by an individual’s location in a social network (Lin 2000). For free agents,

attracting outside options requires maintaining high visibility and cultivating social networks

(Hirsch 1987). To this end, free agents maintain extensive professional networks both within

and outside of the firm. These resources can be used strategically in securing the next job, and in

advancing their careers in general.

While social capital may facilitate career changes for some, it may inhibit mobility for

others. Like the concept of firm-specific human capital, a worker may accumulate social capital

that is specific to the firm, which would be lost if she changed jobs. Fear of losing personal

contacts is the other top reason that workers do not change jobs in Japan (Ono and Rebick 2003).

DATA AND METHODS

I use multiple methods and data in my empirical analysis. I conducted exploratory

interviews with finance professionals in Tokyo to examine preliminary hypotheses and to

generate new ones. These interviews provided an informative starting point from which to

discern the social dynamics of the labor market for finance professionals in Japan, and the key

determinants of their mobility (or immobility). During the time period from 2007 to 2009, I was

able to conduct a total of 28 interviews with finance professionals in Tokyo. All interviews were

conducted in Japanese. Respondents were selected mainly on the basis of snowball sampling.

9

The sample consists of individuals who switched from domestic to foreign firms, as well as those

who have never changed employers.

I conducted statistical analysis from two data sources. The first is individual-level data

from the “Survey of finance professionals” collected by the Nippon Life Insurance Research

Institute in June 1999 (hereafter NLI survey).3 The final sample size of 340 finance

professionals was selected from questionnaires that were distributed to 252 finance firms listed

in the Japan Company Handbook (Kaisha Shikiho, published by Toyo Keizai). The survey

collected a wide range of information relating to the respondent’s employment – e.g. description

of current work, career history, education and training – in addition to the basic demographic

information. 33 percent of the respondents are currently employed in foreign firms.

The second dataset, which I compiled and constructed, is an individual-level database

consisting of security analysts and their career histories (hereafter security analysts database).

Data were collected from analysts featured in the Nikkei Financial Daily. I employ a procedure

similar to Groysberg et al (2008) who collected demographic and job history data of security

analysts featured in Institutional Investor. I briefly describe the data collection process below.

The Nikkei Financial Daily is a Japanese daily newspaper specialized in reporting

financial news. Every week, the newspaper features a column by a security analyst, who

diagnoses a particular company’s financial standing and performance. The column also features

a brief profile of the analyst. A typical profile looks like the following:

Analyst X, Morgan Stanley

Male. Born 1973. Joined Daiwa Securities after graduating with B.A. in Economics from Hokkaido University in

1996. Employed at Morgan Stanley since 2004.

Using a customized template, I then coded this information for a total of 322 security analysts

from the Nikkei Financial Daily between January 2000 and December 2007. 58 percent of the

sample is currently employed in foreign firms. Provided that these analysts were selected to be

featured by the Nikkei Financial Daily, it does call into question the extent to which the current

sample represents the general population of security analysts. We do not have information about

the selection criteria, but presumably these analysts represent the higher end of the ability

distribution. We would therefore not be able to generalize our results beyond this pool of

10

relatively talented analysts. We proceed with care and caution in interpreting the results of our

empirical investigation.

ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

Worker profiles: Who works in the foreign firms?

We begin by profiling finance professionals employed by foreign firms. Table 1 shows

probit coefficients describing the determinants of being employed in foreign firms. Column (a)

shows the results using the NLI data. The basic variables included in this regression are sex,

education, age, and tenure. In addition, we include: (i) foreign university dummy variable

indicating whether the respondent graduated from a university outside of Japan; and (ii) English

certificate dummy variable indicating whether the respondent holds an English proficiency

certificate approved by the Japanese ministry. I also conducted a similar estimation for the

sample of security analysts to predict their entry into the foreign firm. These results are shown in

column (b).

And finally, to distinguish generalists from specialists, we include the variable, years of

specialization (in a specific area of finance) and its quadratic. Here, the areas of specialization

may include for example, financial product development, personal loans, international finance,

mergers and acquisitions, risk management, etc. Workers with longer years of specialization

correspond to specialists, and workers with shorter years of specialization correspond to

“generalists” (not to be confused with general human capital).

It is important to note that years of specialization is a separate measure from tenure. A

specialist may be highly specialized in a particular area of finance for a number of years, but she

may have changed firms in the interim, in which case her years of specialization would be

greater than her tenure. On the other hand, a generalist may have experienced a number of

different sections within the same firm, e.g. through job rotation, in which case her tenure would

be longer than her years of specialization.

The results show some interesting patterns (Table 1). In sum, the profile of finance

professionals in the foreign firms deviates from the status quo in several ways. The average

worker in Japanese firms fits all of the stereotypes of the so-called salaryman figure. He is male,

a graduate from a Japanese university, a generalist, and a job stayer. In contrast, the foreign firm

11

counterpart has a higher likelihood of being a female, a graduate from a foreign university, a

specialist, a job mover, and an English speaker.

TABLE 1 HERE

The issue of selection

A fundamental problem in the empirical analysis concerns the selection of workers into

foreign firms. Much of what we have discussed so far suggests that worker selection into foreign

firms hinges on some systematic process, thus violating the assumption of random selection. I

use the Heckman method (1979) to address the selection problem. We use the probit coefficients

obtained from Table 1 to construct the inverse Mills ratio (λ) which is then entered into the main

equations of interest to correct for selection bias. We use the variable, graduating from a

university outside of Japan, for the exclusion criteria. This variable is a significant predictor of

employment in foreign firm, but it has no effect on the outcomes of interest in our analyses.

Why do foreign firms have higher turnover?

Table 2a shows summary statistics for job changes. In the security analysts data, I also

provide categorical dummies to differentiate the types of domestic and foreign firms, according

to their ranking of security analysts as listed in the publication Institutional Investor for various

years. Top domestic firms include Nomura and Daiwa. Top foreign firms include Deutsche

Bank, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, Nikko Salomon Smith

Barney, and UBS Warburg.4

In both samples, workers in foreign firms have experienced a greater number of job

moves. On average, the number of job changes in foreign firms (versus domestic firms) is

greater by more than one in both datasets. In the security analysts data, we find that there is clear

differentiation among domestic firms, and among foreign firms. Specifically, the firms in

ascending order of job changes are: Top domestic < Other domestic < Top foreign < Other

foreign. The median number of job changes also follows this rank order.

Job mobility may be more common and tolerated in the foreign firms, but these workers

are still constrained by the broader institutional context and the normative environment of the

Japanese labor market. Too much mobility may signal distrust and defection even among the

12

foreign firms. The aversion towards frequent job changers still holds especially among the highstatus foreign firms. One industry insider explained:

At the end of the day, Goldman Sachs in Japan is Goldman Sachs Japan Company Limited. It operates like a

Japanese company, much more so than it does in New York or in London. So there is obviously a lot of influence

from Japanese culture.

Further, since the market for foreign firms is still relatively small, their HR departments

are tightly interconnected. Information about particular candidates travels across firms. Finance

professionals that have reputations for frequent job hopping are identified and given certain

labels, e.g. “gypsies” (Ikaros 2000), and then avoided by some potential employers.

Under the neo-classical framework, mobility is frictionless, and workers are free to move

in and out of firms as they please. But it says nothing about how the high mobility may affect

workers’ reputation in the labor market. In reality, reputations can travel across firm boundaries,

and a reputation for high mobility can impair an individual’s career trajectory.

At the top domestic firms, the median number of job changes is zero, i.e. the majority are

inbred and have never changed jobs. The percentage that has never changed jobs is in fact found

to be 87 percent (not shown here). Clearly there is no culture of high turnover in the top

domestic firms.

Table 2b shows Poisson regressions predicting the frequency of job changes as a function

of firm- and individual-level characteristics. In the Poisson model, the outcome μ is a positive

count. μ has a Poisson distribution with a conditional mean that depends on the set of covariates

x. The basic form of the model is:

μi = exp (xiβ)

(1)

In estimating the frequency of job changes, we account for the fact that different respondents

have different exposure times (t). This is done by multiplying both sides of equation (1) by t

(Long and Freese 2006). Since t = exp (ln t), equation (1) becomes:

μiti = exp (xiβ + ln ti)

(2)

13

In my estimations, we use the respondents’ age as the measure of exposure time.

The results show clearly that workers in foreign firms have higher turnover than do

workers in domestic firms. In the NLI data (column [a]), workers are predicted to have a

turnover rate that is 2.4 times greater (= e0.877) than their domestic counterparts. In Model (b),

we find that analysts who are currently employed in foreign firms have a significantly higher rate

of turnover than do analysts in domestic firms. More interestingly, we find that analysts who

started out in the top domestic firms (as their first employer) are significantly less likely to have

changed jobs, in comparison to analysts who started in other firms. This finding thus suggests

that the point of origin determines the frequency of mobility. Top domestic firms generally have

the most well-established internal labor market setup. They provide the most extensive training,

and pay the highest salaries (among the domestic firms). The cost of defecting – be it economic

or social – can be considerable.

In Model (c), we break down the current employer into four categories, designating the

top domestic firm as the reference (omitted) category. We confirm the same rank order of job

changes, with analysts in top domestic firms predicted to be the least frequent and analysts in

other foreign firms predicted to be the most frequent job changers.

TABLE 2 HERE

We have established that there is greater turnover in the foreign firm. We now

investigate why. Table 3 shows logit coefficients predicting differences in employment

characteristics between domestic and foreign firms using the NLI sample. Each row reports the

results of separate logistic regressions. In the interest of space, I present only the coefficient for

the foreign firm dummy. All regressions control for the vector X and the Heckman selection

term (λ), but these are suppressed from the output.

TABLE 3 HERE

Human capital development

One of the reasons that foreign firms provide less training is because they expect their

workers to be productive immediately. This leads to a key difference in the human capital

14

investment strategy. While workers in domestic firms invest in the firm and build firm-specific

skills, workers in foreign firms invest in themselves, to further specialize in their (general)

professional skills. I examine survey and interview results in light of these key differences.

First, workers in foreign firms have more years of specialization, and less tenure than do

their domestic counterparts (Table 1). On average, the mean years of specialization is greater

than tenure in foreign firms, but the reverse is true in domestic firms. Workers in foreign firms

may change jobs more frequently, but they are less likely to change their areas of specialization.

Second, workers in foreign firms are less likely to undergo job rotation as shown in Table

3. Job rotation is a common HR practice in the Japanese organization (Aoki 2001; Robinson

2003). Workers advance through the internal labor market in an upward spiral, by experiencing

a wide range of assignments in different sections. They may, for example, start out in

investment banking, then move to sales, then to HR or accounting. In so doing, they become

generalists because they develop knowledge and establish personnel networks across a variety of

sections within the firm. Job rotation is less common in the foreign firm. The emphasis is

instead for workers to become specialists, and to develop a deeper sense of professionalism in

their respective areas.

Third, if there is high turnover in the foreign firm, then the worker is also likely to be

working under a supervisor who came from another firm. This is an important but neglected

factor that is related to lower worker commitment. In Table 3, the coefficient for “I work for an

inbred boss” is negative. Here, an inbred boss refers to an internally promoted boss who has

never left the firm. The results thus imply that workers in foreign firms are more likely to be

working under a boss who has previous work experience with another employer.

Interview respondents were quick to point out that their bosses were highly influential in

building their careers. This is partly rooted in the fact that Japan is a highly hierarchical society

to begin with (Nakane 1970), so there is greater dependence between workers and their bosses.

Since the boss usually sets the example, and the subordinate follows, the culture of mobility can

be easily transmitted to the subordinates. One analyst explained: “It’s hard to pledge loyalty to

your employer when your boss himself is not loyal.” The tighter linkage with their bosses also

explains why many bosses invite their team members to change jobs with them. We discuss

these examples in the next section.

15

Fourth, workers in foreign firms are less likely to receive training from the firm. Table 3

shows the responses to the question: Which of the following has helped you improve your

expertise? Workers in foreign firms are less likely to respond that they learned from their bosses,

and more likely to respond that they achieved this through self-improvement. Table 3 also

shows that workers in foreign firms seek better education and training from their firms. These

responses thus reveal the relatively independent work environment of the foreign firm, where

workers are themselves responsible for investments in their human capital. The conditions differ

greatly from the Japanese employment setup characterized by substantial training, and hands-on

coaching from their supervisors.

In the finance profession, it is common market knowledge that domestic firms provide

more training than do foreign firms. Many finance professionals actually take advantage of this

notable distinction. Unsurprisingly, domestic firms become “feeders” for the foreign firms. One

investment banker gave the following advice for young professionals considering a career in the

foreign firm:

It is unwise for graduates to choose a foreign firm as their first employer. They should start in a domestic firm first,

get as much training as they can, then consider the next move.

Nomura in particular is well-known for their extensive training. Many finance

professionals start their careers at Nomura, then migrate to the foreign firms. This pattern has

become so well-established in the profession that the group is known as the Nomura alumni, and

they are highly sought after in the finance profession.5 The Nikkei Financial Daily provides an

annual ranking of the top security analysts. In most of the years surveyed (between 1994 and

2002), Nomura analysts and their alumni claimed more than 50 percent of the top positions

(according to author’s own estimations). The majority of the top ranking analysts are therefore

trained at Nomura.

In sum, the survey and interview results highlight key differences in human capital

development between domestic and foreign firms. Barriers to mobility in the foreign firms are

lower. The market is dictated by the supply and demand for general human capital. Lower

demand for firm-specific skills lowers their barriers to entry and lowers their attachment in the

foreign firms, which further enhances their mobility.

16

Autonomy, independence and self-worth

The next battery of questions concerns the link between performance and pay. Workers

in foreign firms are more likely to respond that: (i) their performance is directly linked to

compensation and promotion; (ii) the firm recognizes the importance of professional skills; and

(iii) they are highly evaluated for their expertise. These results all indicate a tighter linkage

between productivity and pay. Conversely, it can be inferred that the link between performance

and pay is more ambiguous in the domestic firms. This ambiguity stems partly from the

difficulty of placing a value on firm-specific skills, and the tendency to downplay individual

achievement in place of group performance.

A consistent pattern among the professionals that I interviewed was that they demanded

clear recognition for their achievement and performance. Many moved to foreign firms because

they were frustrated with the lack of recognition for individual achievement with their previous

(domestic) employers.

For these reasons, some contend that working in domestic firms is like working under

socialism (AERA 2005). The firm can exert excessive pressure on their workers to conform to

the prevailing norm towards consensus, harmony, and group identity. Those that do not conform

to these conventional views naturally lose their attachment over time. Many migrate to foreign

firms to experience market capitalism in its most naked form (Suenaga 1999). One trader who

moved from Mitsubishi to Goldman Sachs drew a direct analogy to the growing number of

Japanese professional baseball players who are now playing in the Major League in the U.S.

When I was with Mitsubishi, I was reasonably happy, but I always wanted to be in the big leagues. To me,

Mitsubishi is like the Yomiuri (Tokyo) Giants, and Goldman Sachs is like the New York Yankees. Who would turn

down an offer to play in the Major League?

If workers in foreign firms value independence and autonomy, then we would expect that

they are less likely to work in teams. The results, shown in the last row of Table 3, indicate that

teamwork is equally valued in the foreign firm as it is in the domestic firm. I shall follow up on

this in the next section.

17

The perception of time

Another consistent opinion in the interviews concerns the different perceptions of time.

Domestic firms are widely recognized for their long-term vision. Domestic firms provide

extensive training, with the expectation that the employment relationship will be long-lasting. In

the gift exchange rhetoric (Akerlof 1982), firms invest in their workers, with the expectation that

this gift will be repaid later on in their careers. But some workers may not appreciate the gift,

because it pushes back the timing of working and being rewarded in accordance to their marginal

product.6 Further, given the higher frequency of job rotation, workers may have to endure time

served in various sections of the firm until they are able to work in the job that they truly desire.

Clearly, the workers in the foreign firms have less employment security than do their

domestic counterparts, but this is of course an outcome of their rational decisions. As Baron et al

(2001) explain, “Employees who consider joining a firm that has a history of espousing a

particular model are likely to have a good sense of what they will encounter” (p.973).

Interview respondents who were employed by foreign firms repeatedly remarked that

they did not have the patience to deal with the long-term orientation of the Japanese firm, and

that they wanted to put their skills to use immediately. One respondent remarked that working in

Japanese firms is like working under hypnosis. Another respondent made the analogy to the

rabbit and the tortoise, to highlight the relatively slower pace of work in the Japanese firm.

Workers do not have the sense of urgency because they are in a long-term employment

relationship, and they know that they cannot be dismissed. Baron (1988)’s imagery of Newton’s

first law of motion may be appropriate here: “employees remain in a state of rest unless

compelled to change that state by a stronger force impressed upon them” (p.494).

In sum, the cluster of HR practices in place within the domestic firms is held intact

through institutional complementarities. Extensive training and job rotation within the firms

leads to the accumulation of firm-specific skills which results in an implicit, long-term

employment. Because it is difficult to place a value on firm-specific skills, the link between

individual performance and pay is ambiguous. These conditions do not hold true in the foreign

firms, because the HR practices there are less interdependent. Since they are better endowed in

human capital that is marketable elsewhere, they are fully aware of their market worth.

Accordingly, there is a clear link between their productivity and pay.

18

Analysis of movers

We now examine career mobility among the movers in the NLI sample. Here, movers

are defined as those who have previous work history with a different employer. Of the full NLI

sample of 340, there were 101 movers. The current analysis is restricted to this subsample.

TABLE 4 HERE

Table 4 shows responses to a number of questions from the NLI survey regarding career

changes. The outcome variable here is a yes/no binary response. I ran logistic regressions to

predict the “yes” outcome for each survey question. Table 4 shows only the coefficient for the

foreign firm dummy. All regressions control for the vector X and the Heckman selection term

(λ), but these are suppressed from the output.

We first confirm that workers who are currently employed in foreign firms are more

likely to have moved there from a foreign firm. We also confirm that workers who moved to

foreign firms resulted in higher salary.

We now examine the reasons for moving. Recognition for individual performance is

highly valued among workers in foreign firms. This finding is largely consistent with the earlier

claim, that workers migrate to foreign firms in pursuit of greater individual recognition.

Higher pay is a less important motive for moving to foreign firms. In fact, the response

rate is statistically insignificant between workers in domestic and foreign firms. This finding

does not necessarily contradict the one above. The two findings suggest that workers on average

end up with higher salary as an outcome of moving to foreign firms, but higher pay is not

necessarily the main motive for their move. The trader from Goldman Sachs explained that his

main motivation for moving was greater recognition, and his desire to test his skills in the big

leagues.

Goldman Sachs offered a higher compensation package than the one at Mitsubishi. But this was not the reason for

my move. I moved because they were a foreign firm. If Nomura had offered a higher salary, for example, I would

not have moved. (emphasis mine)

19

Job matching

We next examine how workers are matched to employers. We are particularly interested

in examining here the role of information in searching for jobs. Table 4 results do not show a

definitive pattern in the job search method. Workers in foreign firms were less likely to use

newspaper ads, suggesting that they found employers through other informal means. But they

were more likely to find jobs via headhunters. The other results – via acquaintance and via direct

invitation – are both insignificant.

Headhunters play a big role in job search for foreign firms (Ikaros 2002; Robinson 2003),

a point which was mentioned frequently in the interviews. Some respondents were approached

by headhunters, while others approached headhunters themselves to find their next jobs. And

still others made it a point to meet periodically with headhunters to learn about their market

worth, and also to update the headhunters with their latest achievements. Headhunters have

enormous databases of information, but that information can get old, according to one

investment banker in my interviews. He felt that it was in his interest to update his information

with the headhunters.

I learned during my interviews that there exist headhunters that specialize exclusively in

placement into foreign firms. This market niche suggests that the demand for midcareer

placement is considerably larger among the foreign firms. The internal labor market structure of

domestic firms is not accommodating to midcareer professionals. Domestic firms, in turn, are

not looking to hire midcareer professionals.

Team mobility and social capital building

The one recruitment channel that is not mentioned in the survey, but was raised

consistently in the interviews is the role of the former boss. Without doubt, bosses are

instrumental players in finding jobs and more generally, in advancing their careers. Because

finance professionals often work in teams, it is common practice for them to migrate in teams.

These teams then build up team-specific capital (Groysberg et al 2008) – be it human capital or

social capital – which loses value if broken up into smaller parts. The importance of maintaining

a good reputation with former bosses was emphasized repeatedly in my interviews.

One famous story in the finance sector is the case of the mergers and acquisition (M&A)

team at Merrill Lynch. The section head of the M&A team spun off and launched his own

20

company specializing in the M&A business. When he quit, he took his entire team with him,

thus leaving the M&A section at Merrill Lynch vacant and scrambling to fill up these vacancies.

Social capital can facilitate mobility in some situations, and constrain it in others. A

veteran researcher in a large domestic brokerage firm explained how he built his “empire” there.

Over time, I drew upon my resources and built my own “empire.” And once you build your empire, you are locked

in. If I were to move, I think about how many phone calls I have to make internally. I really cannot put a value on

this network I have built in-house. The headhunters used to call me frequently when I was younger, but they

stopped calling because they realized that I cannot be bought.

This is a notable example of firm-specific social capital. Clearly, his reason for not moving is

social and not economic; he does not move because the social costs outweigh the benefits.

In sum, the findings from the analysis of movers underscore the important role of

information in the job matching process. Workers in foreign firms are sufficiently informed

about potential job opportunities, and they are well informed about their own market worth.

These workers maintain close ties with their supervisors, and communicate regularly with

headhunters. These investments in information and social capital improve the quality of the job

match, and facilitate their career mobility.

Career mobility among security analysts

In our final analysis, we examine career mobility among security analysts. We are

primarily interested here in examining the extent to which mobility is barrier free. Empirically,

this corresponds to the condition of random mobility; there is no dependence between the origin

and destination.

In Table 5, column (a) records the number of job moves, which ranges from zero for nonmovers up to five for those who experienced six employers. Column (b) records the number of

employers, ranging from one to six. Column (c) records the number of persons corresponding to

each category, and column (d) records the total number of moves, which is the number of moves

multiplied by the number of persons.

The most frequently observed pattern is the group of non-movers in the domestic firm.

Among the total sample of 322 analysts, 91 (or 28 percent) fall in this category. In contrast, only

9 analysts (or 3 percent) are in the category of non-movers in the foreign firm. Only 40 analysts

(or 12 percent) started out in foreign firms. This is consistent with earlier discussion, that foreign

21

firms are generally the destination and not the origin of careers. We begin to see a pattern where

the domestic firms are positioned as “feeders” for the foreign firms. As suggested by interviews,

these analysts may be taking advantage of the extensive training offered by domestic firms, then

moving on to the foreign firms where they can be rewarded with higher compensation or greater

personal recognition.

I highlight the transition from foreign (F) to domestic firms (D) using boxes in Table 5.

The results again clearly show the un-likelihood of this move. Only 20 analysts moved from

foreign to domestic firms. This is just 6 percent of the total number of analysts, or 5 percent of

the total number of possible moves shown here. With respect to first jobs, 88 percent started off

in domestic firms. With respect to current jobs, this ratio firms drops to 42 percent.

TABLE 5 HERE

Table 6 presents the mobility table that illustrates how security analysts move from their

origins to their destinations. The left-hand column shows the origins, i.e. their first employers.

The remaining columns are the destinations of their first job move. The firms listed in Table 6

are the top performing financial institutions that employ the highest ranking security analysts, as

tabulated and ranked by Institutional Investor, and other publications in finance.

TABLE 6 HERE

The numbers in the cells indicate job-moves. If a person moves from Nomura to

Goldman Sachs, then this is recorded as a job move. If the person does not move at all, then this

is recorded in the diagonal. In this way, I recorded all analysts and their career mobility patterns.

The results are striking. There is a clear association between the origin and destination, thus

rejecting the condition of barrier free mobility.

Domestic firm is the origin, foreign firm is the destination. The domestic firms feed

analysts into the foreign firms. This can be read directly from Table 6. We observe a

conspicuous pattern where the total outflow is greater than the total inflow among the domestic

firms, and a reverse pattern among the foreign firms. For example, there were 48 analysts who

22

originated at Daiwa and 24 who remain there. On the other hand, 3 analysts started at Goldman

Sachs, but 15 ended up there.

Mobility and immobility at the top. The top two domestic firms have the highest share of

immobility than do other firms. Among those who start in these firms, about half remain as

recorded in the last column of the table labeled “% stayers.” For the movers from these top

domestic firms, the destinations are the top foreign firms. For the analysts in the other (lowerstatus) domestic firms, the majority move on to the lower-status foreign firms.

Point of origin determines not only how frequently these analysts move between jobs

(Table 2b), but also where they move. Analysts from the top domestic firms move to top foreign

firms. Of the 33 analysts who left Nomura, 67 percent were placements into the high-status

foreign firms. At Daiwa, this ratio was 71 percent. In contrast, among the other domestic firms,

placement into the high-status foreign firms was only 33 percent.

Moving into the top two domestic firms is virtually impossible. Mobility into Nomura

and Daiwa from foreign firms was zero. Nine analysts moved into the two top domestic firms,

but these moves originated from other domestic firms. This finding confirms again the rigid

internal labor market setup of the top Japanese firms, and the barrier to entry for midcareer

professionals. An analyst from Nomura Securities explained as follows:

We are gradually adapting to the competitive environment in the finance sector, but we are still a Japanese company.

This means that we train our analysts in-house, and we still try to fill vacancies internally.

Interestingly, there is no mobility between the top two domestic firms; no one moves

from Nomura to Daiwa, or the other way around. One possible explanation is because these are

the top two domestic competitors, so mobility between competitors may be limited. But more

relevant to our discussion is the position that changing employers under the Japanese

employment system is a deviant act and a breach of the implicit contract. Quitting a Japanese

employer has enormous consequences for subsequent career trajectories, much more so than

quitting a foreign one. If one were to move, s/he will do so with the maximum benefit. Hence,

as one analyst explained, “it would not make sense to move to another Japanese firm which

offers the same pay scale and level of compensation.” This is another reason why most analysts

that quit the top domestic firms end up in the top foreign firms. It also explains why only one

analyst from Nomura and one from Daiwa moved to the other (lower-status) domestic firms.

23

Team mobility. In Table 6, we observe that mobility from the top domestic firms to the

top foreign firms is not random. For example, at Nomura, 8 analysts moved to Goldman Sachs;

at Daiwa, 7 moved to Deutsche Bank. While there is a strong Nomura-Goldman Sachs

connection, there is no migration from Nomura to Deutsche Bank.

This herd behavior could be related to team migration or some type of an institutional

linkage between firms, although the numbers are too small to make statistical inferences.

Working in teams is standard practice among security analysts, be it domestic or foreign. When

one moves, s/he may take their team members with them, especially if s/he happens to be a team

leader. One analyst at Deutsche Bank explained:

At one point there was a massive influx of analysts that came from Daiwa Securities. Much of this move was

initiated by upper-level managers who were formerly at Daiwa, and they pulled their teams into Deutsche. In some

cases, an entire section can be formed of Daiwa analysts.

An underwriter at Morgan Stanley explained:

In the 1990s, there was a strong presence of Nomura Securities at Morgan Stanley, because we had a leader from

Nomura. We poached a lot of specialists from Nomura, and fired our own. These days, we have a strong presence

from Daiwa Securities.

Heterogeneity: The positive association between workforce heterogeneity and turnover is

one of the key claims in the organizational demography literature (e.g. Sorensen 2000). If

outflow is greater than inflow in the domestic firms, and the opposite is true in the foreign firms,

then we would expect greater heterogeneity in the foreign firms.

In Table 6, the last two rows report the percentage of analysts that are inbred, and the

index of differentiation in each firm. I note that the numbers reported here are approximations.

Since I only tabulate the first job change, the destination is the second employer which is not

necessarily the current employer (I re-estimated the numbers using a table that records the

current employer instead of the second employer, and achieved similar results). Also, the sample

of analysts recorded here is not comprehensive, but a sub-sample that was featured in the Nikkei

Financial Daily. The reported numbers should be interpreted in the context of these

simplifications.

For each firm, the index of differentiation is estimated by the following equation (Gibbs

and Poston 1975):

24

C

Index of differentiation = 1

N

i 1

2

i

C

Ni

i 1

2

(3)

where N is the number of analysts who moved to the current employer from firm i. The index is

bound by the absolute minimum of zero, and a relative maximum, 1 – 1/C where C is the number

of previous firms represented in the current employer. The condition of zero heterogeneity, or

perfect homogeneity is achieved when C is equal to one, or when all analysts in the firm come

from the same origin.

We first observe that the percentage of inbred analysts is over 85 percent in the top

domestic firms. This is a remarkably higher percentage compared to 5 percent in the top foreign

firms, and 2 percent in the other foreign firms. These numbers confirm that the culture of

inbreeding – where analysts are trained and raised internally – remains the norm in the top

domestic firms, and a culture of poaching is pervasive in the foreign firms.

Accordingly, we find that the index of differentiation is low – 0.23 and 0.27 – in the top

domestic firms, and high in the top foreign firms, where it ranges from 0.69 to 0.97. The

heterogeneous composition of the analysts at foreign firms can be confirmed by eyeballing the

numbers on Table 6. At Morgan Stanley for example, there are analysts who moved there from

Nomura, Daiwa, and JP Morgan, as well as other domestic and other foreign firms. This

demographic heterogeneity is both the cause and the outcome of high turnover in the foreign

firms. The low percentage of inbred workers means that there is a large influx of workers with

previous experience. The large influx results in a more diverse and heterogeneous workforce,

which in turn leads to higher turnover.

Finally, I estimate mobility probabilities between origins and destinations among the

security analysts. Table 7(a) shows the 5 × 5 mobility table. This is a collapsed version of Table

6 where I group the top foreign firms into one category. I compare five different specifications

of models. Four of these are standard in the literature – independence, quasi-independence,

symmetry, and quasi-symmetry. In the fifth model, I construct my own design matrix as shown

in Table 7(b), which I call the asymmetry model. Our analysis thus far has found strong

25

evidence that the mobility from domestic to foreign goes only in one direction. The asymmetry

model is a direct test of this one-way transition. I hypothesize that the mobility between the

origin and destination is not symmetric across the diagonals. The designated reference category

is cell number 1 which corresponds to immobility in the top domestic firms, i.e. this is the group

of analysts in the top domestic firms that did not move. I note one caveat here. In the three

diagonal cells numbered 5, we are unable to distinguish between those who moved and those

who did not. For example, in the category of top foreign firms, cell 5 is confounded by the

immobility of analysts who remained in the top foreign firms, as well as the transition of analysts

that moved from one top foreign firm to another top foreign firm. The pattern of immobility is

rare among the foreign firms and in the other domestic firms (as shown in Table 6), but we

cannot rule out the possibility that the parameter estimates in these three diagonal cells may be

confounded by this heterogeneous population.

TABLE 7 HERE

I estimate mobility probabilities by fitting generalized linear models where the link is the

natural logarithmic function, and outcome y takes on a Poisson distribution:

ln {E(y)} = xβ

y ~ Poisson

(4)

Table 7(c) shows the model comparisons. The asymmetry model, which assumes an

asymmetric pattern of mobility between domestic and foreign firms, achieves the best fit as

evaluated by the BIC statistics. The significant improvement over the independence model

suggests that the condition of no association between origin and destination (corresponding to

null hypothesis condition [1]) is rejected. I proceed to present results of the asymmetry model in

Table 7(d).

All parameters in Table 7(d) are negative, thus indicating that all patterns of mobility

shown here are less likely to occur compared to the reference group of immobility between the

top domestic firms. We again confirm the overwhelming pattern of one-way transition from the

domestic to the foreign. The results clearly show that the transition into the domestic firms is

significantly less likely to occur than is the transition into the foreign firms, regardless of origin.

26

The coefficients reported under the top domestic firms and other domestic firms are significantly

more negative than the ones reported under top foreign and other foreign.7 Regardless of one’s

origin, analysts who change jobs in midcareer are more likely to end up in foreign firms. These

findings are consistent with the commonly observed cycle of job hopping in the foreign firms.

Moreover, we confirm that entry into the top domestic firms from any firm is highly

restricted. Among the four columns, the coefficients for top domestic are the most negative.

Analysts who started their careers elsewhere are unlikely to find midcareer opportunities in the

top domestic firms.

If analysts in the top domestic firms move, they are least likely to move to other domestic

firms. As discussed earlier, there is no incentive for these analysts to move to another domestic

firm, because any domestic firm will be inferior to their current employer. If they move at all,

analysts from the top domestic firms will choose foreign firms as their destinations because of

the reasons aforementioned – higher salaries, better recognition of their worth, etc. And if they

have the choice, they will choose the top foreign firms over other foreign firms because the

benefits generally are better there. This is in fact what we find. For the analysts from the top

domestic firms, the likelihood of mobility is lowest going into other domestic firms, and highest

for the top foreign firms.

SUMMARY

There is greater turnover in the foreign firm. Workers in foreign firms change employers

more frequently, and they are more likely to be hired under short-term contracts. The

higher turnover is related to human capital development and skill formation. Foreign

firms do not offer training, so the workers do not acquire firm-specific skills. These

workers invest mainly in general skills, which improves their outside options, and

subsequently weakens their attachment to the firm.

Mobility is not entirely uninhibited and barrier-free. Job mobility in the Japanese

financial sector is not flexible in all directions, but “sticky.” Workers only move in one

direction, from the domestic to the foreign, and not the other way around. Instead of

random mobility between origin and destination, there is a systematic pattern where the

destinations are determined by their origins.

27

The top domestic firms serve as feeders for the foreign firms. Workers in the domestic

firms receive extensive training, then migrate to the foreign firms where they can receive

higher compensation. Lastly, instead of an atomized pattern of individual mobility, we

find evidence of team mobility, dictated by informal contacts between workers and their

former bosses.

Finance professionals move in teams. They do so because they have built team-specific

capital that can be transferred with the team across firm boundaries, but that is difficult to

rebuild if the team is broken up.

Workers are not anonymous and identity is important. Workers want to maintain a

positive reputation with their bosses because the bosses will pull them into the valuable

jobs. Workers avoid the reputation for job-hopping, because excessive mobility signals

defection even among the foreign firms.

Workers in foreign firms are better informed about their outside options than are their

domestic counterparts. They know their market worth. They cultivate professional

networks, maintain contacts within and outside of their organization, and actively

exchange information. They use headhunters strategically, to keep themselves informed

of outside options, and to periodically reassess their market value.

Foreign firms offer higher salaries on average, but this is not the key driver of mobility.

The main motivation for moving is the pursuit of greater personal recognition. Many

workers who migrate to foreign firms do so because they do not conform well to the

group-oriented approach of the Japanese organization. They seek positions in foreign

firms because they value recognition for individual achievement over the long-term

orientation of the domestic firm.

For some, the cost-benefit calculation is more social, and economic motivation is less

important. They build and invest in firm-specific social capital. The social costs of

moving outweigh the economic benefits from moving.

Workers in foreign firms receive compensation that is more closely tied in to their own

performance and contribution. It is also easier to place a value on general skills than it is

on firm-specific skills.

28

Discussion

The current study has shown that whether one is loyal to the employer or not depends less

on individual attributes, and more on the institutional context that she is situated in. The findings

weaken cultural perceptions of the highly-committed Japanese worker by demonstrating that

loyalty is endogenous. Japanese workers in foreign firms are highly mobile and they show little

signs of loyalty.

At the same time, we uncover evidence which suggests that foreign firms adapt to local

labor market conventions. The Japanese financial sector operates under different notions of

organizational legitimacy; the highly atomized and market-driven Anglo-American approach can

be implanted but only up to a point. Referring back to Figure 2, firm M and firm K are distinct

organizational forms by virtue of their differing positions of marketness. However, firm K may

be a highly market-oriented firm in Japan, but it is still lower on the marketness scale compared

to firm L. For example, workers are free to move but too much mobility could send a bad signal

in a market where the status quo is still low mobility. Career mobility in the embedded market is

thus constrained by social conventions.

Over time, the Japanese employment system is destined to move from social to the

economic mode of exchange (Murakami and Rohlen 1992). Along with globalization, the

foreign firms are increasing their market presence in the Japanese economy. As Westney (2001)

explains, these global pressures are pushing Japan’s business practices towards a systematic

model for change: The move to U.S.-style shareholder capitalism. Recent reactions by domestic

firms illustrate best the pressure to normalize and to converge to global competition. Domestic

firms lost their best and brightest to the foreign firms during the 1990s. For the first time,

Nomura’s uncontested top position in the analyst rankings started to slip. The following excerpt

from Institutional Investor describes the brain drain problem, and how Nomura is fighting back:

To some, Nomura’s slip reflects the same problem that equity researchers are grappling with at many of the

Japanese companies they follow: a resistance to change. The country’s largest brokerage firm remained true to

Japan’s seniority-based system of compensation for most of the past decade -- and paid a price. Scores of young,

talented analysts defected to U.S. and European banks, where the pay structure is weighted more toward merit than

tenure… It wasn’t until February of last year that Nomura revamped its research compensation system to be more

competitive, a move that has met with some success. The firm didn’t lose a single analyst to a competitor last year

and even managed to rehire a former analyst. (Shimizu 2001)

29

Throughout my interviews, I learned about specific actions that the domestic firms are taking to

counter the exodus of their best human capital, e.g. introducing separate career tracks for

specialists, and overhauling the compensation system to better match that of the foreign firms.

These actions, especially calling back their former people who defected to the foreign firms,

would have been unthinkable under the traditional Japanese employment system.

From the viewpoint of institutional complementarities, these market corrections will

undermine the overall interdependence of HR practices, and may eventually destabilize the

Japanese employment system. But such actions may be inevitable in the face of globalization

and increased market competition from the foreign firms.

At the same time, there are signs that some foreign firms are moving towards an internal

labor market setup. In Figure 2, the domestic firms (M) are moving in the direction of higher

market orientation, and foreign firms (K) are moving towards non-market orientation. For

example, foreign firms that have a longer history of conducting business in Japan are now

systematically recruiting new university graduates and intensifying their internal training (Ikaros

2002). These recent developments in both domestic and foreign firms suggest a pattern of

convergence (Jacoby 2005). The co-existence of domestic and foreign firms, and the expanding

presence of the latter are fascinating areas of research, and I reserve this for my future work.

Notes

1

Lifetime employment figures are estimated from Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare statistics using method

described by Ono (2010). It measures the number of workers in the age group 50 to 54 who have never changed

employers divided by the total number of workers in that age group.

2

For example, JILPT (2005) reports that the percentage of midcareer hires in domestic firms was 60 percent in

domestic firms, compared to 82 percent in foreign firms.

3

The NLI data was provided by the Social Science Japan Data Archive, Center for Social Research and Data

Archives, Institute of Social Science, The University of Tokyo.

4

I experimented with several variations of these classifications, and achieved similar results.

5

Source: Nihon Keizai Shimbun. 2005. “Nomura soken, jiyu ou DNA” (Nomura Research Institute: Opportunities

and freedom). September 19, 2005.

6

This is the case of deferred compensation. If workers accept the training, they will be paid lower than their

marginal product, and they will have to wait until the training period is over to recoup their losses.

7

The one exception here is the transition from top foreign to other domestic (cell 11), and the transition from top

foreign to other foreign (cell 12). The coefficient in cell 11 is more negative than the one in cell 12, but this

difference is not statistically significant.

30

References

Abegglen, James C. 1958. The Japanese Factory: Aspects of Its Social Organization. Glencoe: Free Press.

AERA. 2005. Gaishikei he yokoso. (Welcome to the Foreign Firm). Tokyo. Asahi Shimbunsha.

Akerlof, George A. 1982. “Labor Contracts as Partial Gift Exchange.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 97:543-569.

Aoki, Masahiko. 2001. Toward a Comparative Institutional Analysis. Cambridge: MIT Press.