BJCP_Notes_-_September_2011_-_Cider

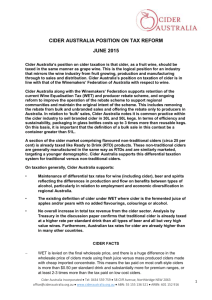

advertisement